Future pandemics could arise from an accident (a pathogen being used in research accidentally infecting a human). The risk from accidental pandemics is likely increasing in line with the amount of research being conducted. In order to prioritise pandemic preparedness, forecasts of the rate of accidental pandemics are needed. Here, I describe a simple model, based on historical data, showing that the rate of accidental pandemics over the next decade is almost certainly lower than that of zoonotic pandemics (pandemics originating in animals).

Before continuing, I should clarify what I mean by an accidental pandemic. By 'accidental pandemic,' I refer to a pandemic arising from human activities, but not from malicious actors. This includes a wide variety of activities, including lab-based research and clinical trials or more unusual activities such as hunting for viruses in nature.

The first consideration in the forecast is the historic number of accidental pandemics. One historical pandemic (1977 Russian flu) is widely accepted to be due to research gone wrong, with the leading hypothesis being a clinical trial. The estimated death toll from this pandemic is 700,000. The origin of the COVID-19 pandemic is disputed, and I won’t go further into that argument here. Therefore, historically, there have been one or two accidental pandemics.

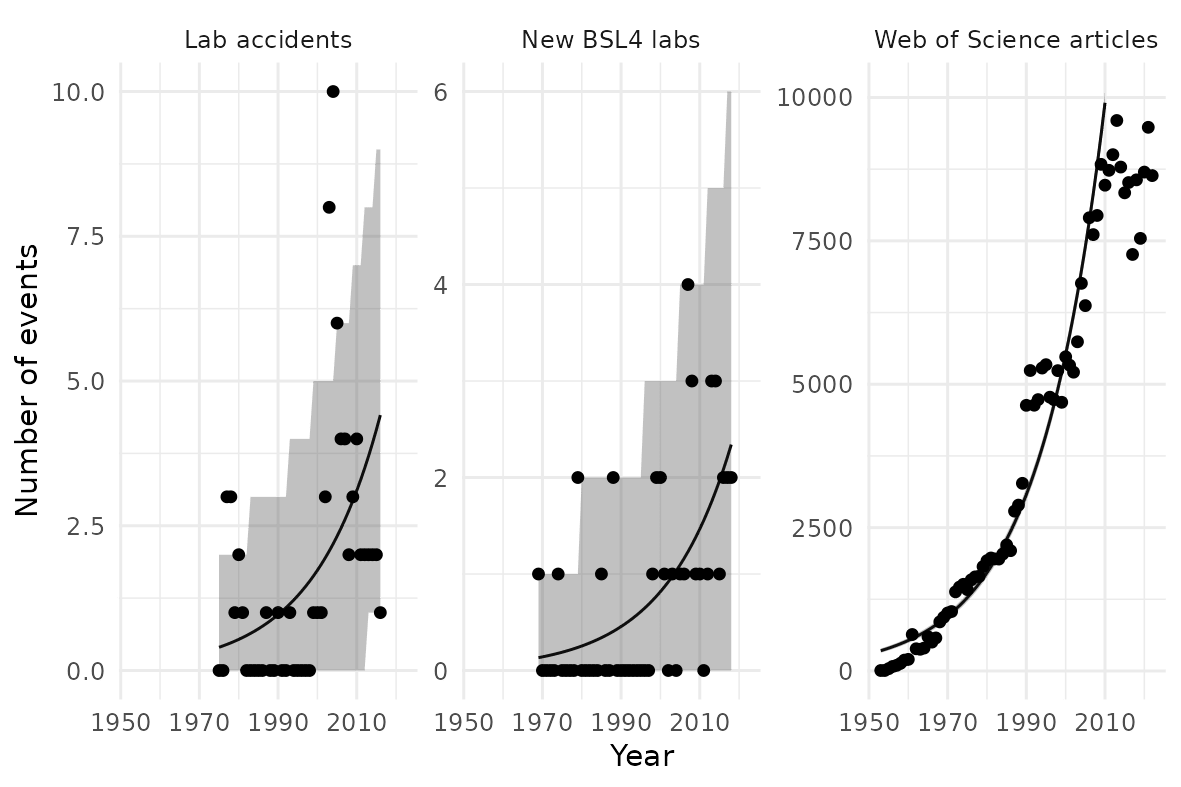

Next, we need to consider the amount of research that could cause such a pandemics, or the number of “risky research units” that have been conducted. No good data exists on risky research units directly. However, we only need a measure that is proportional to the number of experiments.[1] I consider three indicators: publicly reported lab accidents, as collated by Manheim and Lewis (2022); the rate at which BSL-4 labs (labs handling the most dangerous pathogens) are being built, gathered by Global BioLabs; and the number of virology papers being published, categorised by the Web of Science database. I find a good fit with a shared rate of growth at 2.5% per year.

A plateau in the number of virology papers in the Web of Science database is plausibly visible. It is too early to tell if this trend will feed through to the number of labs or datasets, but this is a weakness of this analysis. However, a similar apparent plateau is visible in the 1990s, yet growth then appeared to restart along the previous trendline.

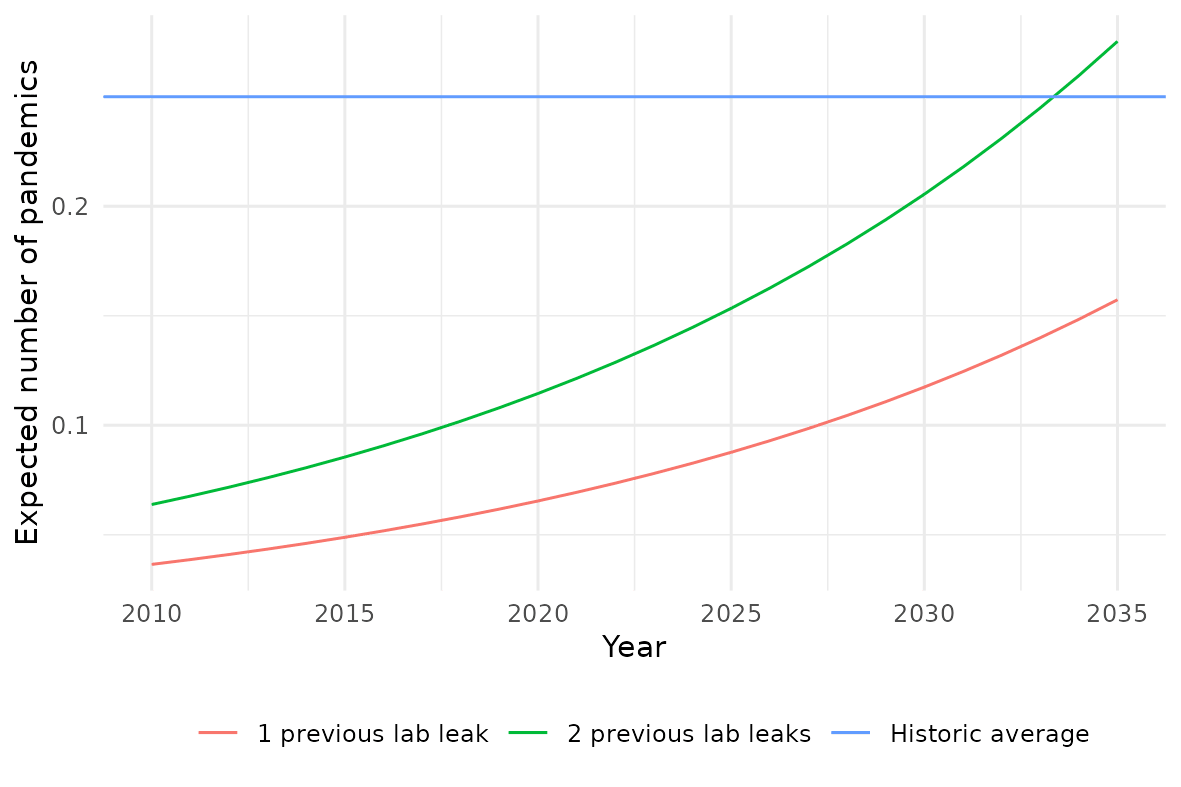

The final step is to extrapolate this growth in risky research units and see what it implies for how many accidental pandemics we should expect to see. Below I plot this: the average (expected) number of pandemics per year. Two scenarios are considered: where the basis is one historical accidental pandemic (1977 Russian flu) and where the basis is two historical accidental pandemics (adding COVID-19). For comparison, I include the historic long-run average number of pandemics per year, 0.25.[2]

Predictions for the ten years starting with 2024 are in the table below. This gives, for each scenario: the number of accidental pandemics that are expected, a range which the number of pandemics should fall in with at least 80% probability, and the probability of at least one accidental pandemic occurring.

| Scenario | Expected number | 80% prediction | Probability at least 1 |

| 1 previous | 1.2 | 0-2 | 56% |

| 2 previous | 2.1 | 0-3 | 76% |

Overall, the conclusion from the model is that, for the next decade, the threat of zoonotic pandemics is likely still greater. However, if lab activity continues to increase at this rate, accidental pandemics may dominate.

The model here is extremely simple, and a more complex one would very likely decrease the number forecast. In particular, this model relies on the following major assumptions.

First, the actual number of risky research units is proportional to the three indicators chosen. That all three indicators are growing at similar rates lends credence to this view. However, this assumption is, in practice, almost impossible to verify. Each of the datasets used here have issues,[3] and further work here would certainly be useful.

Second, the number of risky research units is growing exponentially, and this will continue over the extrapolation period. The plateau in the number of virology papers being published is the most concerning feature of the data here. This implies that the number of risky research units might be slowing down in growth. On the other hand, increasing access to biological research could cause an increase in risky research, but I think a step-change over the next decade is unlikely.

Third, the probability of an accidental pandemic per risky research is constant. This seems unlikely. Biosafety (actions to reduce the risk of lab accidents) is becoming more prominent and, like most of society, safety measures are increasing. This is especially true in comparison to the 1970s, when the Russian flu pandemic occurred. In fact, rerunning the above projection but only considering that there was 1 accidental pandemic by 1977 implies a more than 90% probability of two or more accidental pandemics by the present day. However, as risky research is done more broadly (e.g.: in less developed countries) biosafety may decrease. Hence, the current risk of an accidental pandemic per risky research unit is overstated by this analysis, but this is uncertain.

Fourth, and finally, the occurrence of accidental pandemics is independent. We might expect that, if a future pandemic was confirmed to be leaked from a lab, actions would be taken to reduce the probability of a future one. While this would not affect the view of the probability of at least one accidental pandemic, it should reduce the probability of two or more, and hence the expected number too.

These factors imply that the model here is overestimating the likely rate of future accidental pandemics. Therefore, it is almost certain that accidental pandemics are currently not the majority of pandemics we’d expect to see, even based on this model which likely overestimates their frequency. This may change towards the end of the projection period, hence, considerations over improved biosafety are still important.

In order to fully assess the relative impact of accidental pandemics, compared with other sources, it is also important to consider their severity. In general, I would expect the types of pathogens that research is being conducted on to be similar to those we expect to see pandemics. However, there may be a bias towards more severe pandemics since these are the ones which we would most want to prevent or mitigate.

Thank you for reading to the end. I am currently looking for a job! If you think your organisation could benefit from this type of thinking, please get in touch.

Many thanks to Sandy Hickson and Hena McGhee for commenting on drafts of this post, and the Cambridge Biosecurity Hub for many discussions informing my thinking. I am also grateful to the researchers who released the data I used: David Manheim, Gregory Lewis, the Global Biolabs project, and Web of Science.

- ^

Assuming exponential growth, which appears to be a good fit, growth at the same rate implies a constant multiplier between the different indicators. The gamma-Poisson model employed for the prediction makes the same predictions if the amount of risk being incurred is scaled by a constant multiplier. Mathematical details are available in this R Markdown notebook.

- ^

Using the dataset of Marani et al. (2021).

- ^

BSL-4 labs are a small subset of all research, and have small numbers. The lab accidents dataset (from Manheim and Lewis) is likely incomplete, and possibly biased. Virology papers do not necessarily track risky research.

Executive summary: A simple model based on historical data suggests the rate of accidental pandemics originating from research activities over the next decade is likely lower than that of zoonotic pandemics, but could become more prominent if risky research continues growing exponentially.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.