Summary

We're optimistic that GiveWell's funds raised will continue to increase in the long run. Over the next few years, we believe our annual funds raised are more likely to stay relatively constant, due to a decrease in expected funding from our largest donor, Open Philanthropy, offset by an expected increase in funding from our other donors.

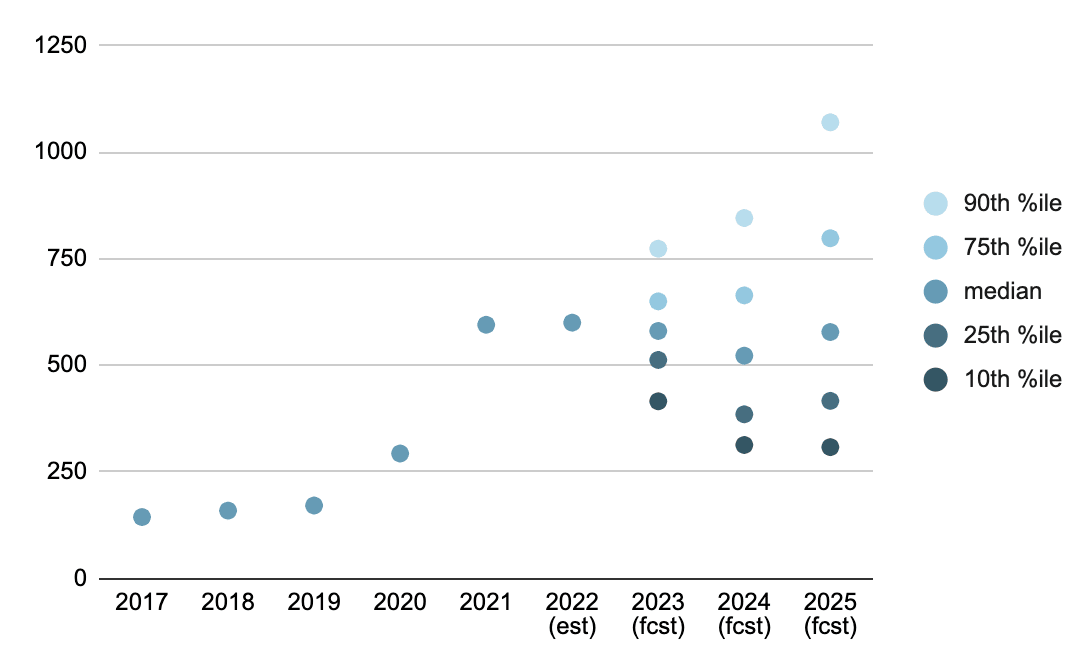

This chart shows our latest forecasts for funds raised in millions of dollars:[1]

In November 2021, we wrote that we were anticipating rapid growth and aiming to influence $1 billion in 2025. Now, our best guess is that we'll raise between $400 million and $800 million in 2025 (for comparison, we raised around $600 million in 2022). As in the chart above, we now think it's possible but unlikely that we'll raise close to $1 billion in 2025, and we also think it's possible but unlikely that our funds raised in 2025 will be substantially lower (e.g. around $300 million) than they were in 2022.

We're excited about the impact we can have at any of those levels of funding, and we'll be continuing to direct as much funding as we can raise to the most cost-effective opportunities we can find.

Our forecasts are uncertain. We might be wrong about what the future will look like, just as our projections now are very different than they were in late 2021. We'll have better information as time goes on.

This change in projected funds raised means that:

- We're funding-constrained: we believe that our research will yield more outstanding opportunities than we'll be able to fund over the next few years. Your donations can help fill those gaps.

- Because it's valuable to maintain a stable cost-effectiveness bar, we may not spend down all the funds available to us in each year. Depending on how much funding we are able to direct and when it becomes available, we may smooth our spending over the next few years. Currently, we recommend funding to opportunities we believe to be at least 10 times as cost-effective as unconditional cash transfers ("10x cash").

- We are increasing our emphasis on fundraising relative to past years and relative to our previous plans for 2023 to 2025 in order to increase the chances of us being able to fill additional cost-effective funding gaps.

In the rest of this post, we discuss:

- Our updated forecasts

- How we'll respond to shifting expectations

- The uncertainty inherent in these projections

Our updated forecasts

When we wrote that we aimed to direct $1 billion annually by 2025, we were imagining a scenario in which we'd receive $500 million from Open Philanthropy and roughly $450 million from other donors.[2]

We now believe that:

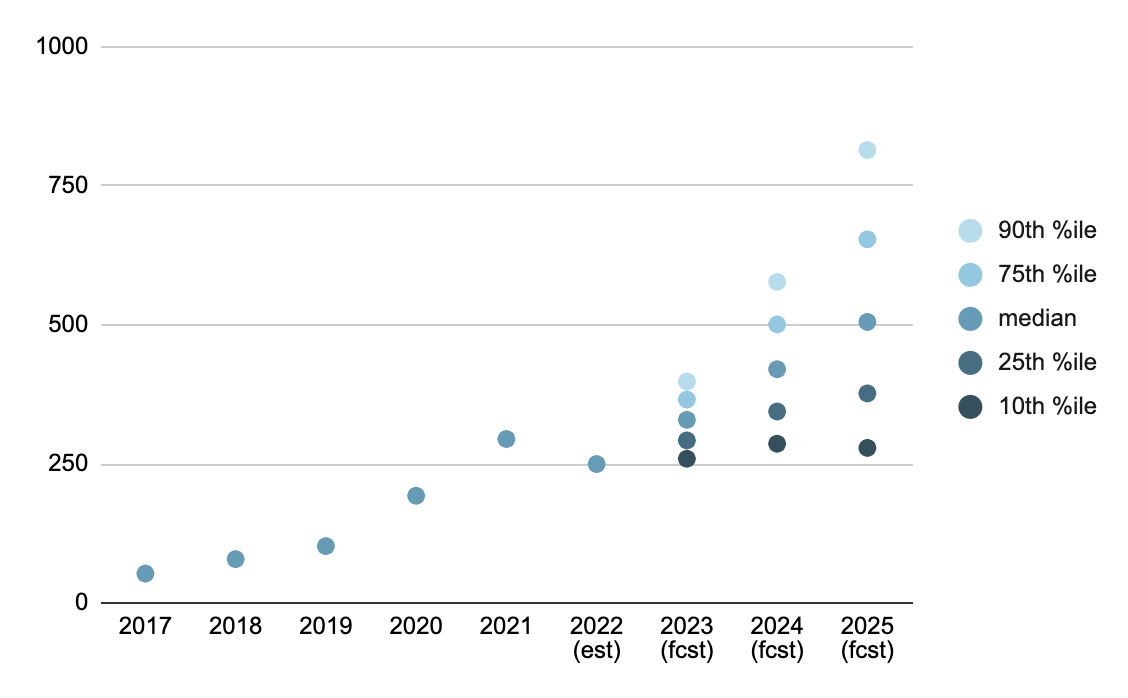

- Given our strong community of supporters and our increased fundraising efforts, funding from donors beyond Open Philanthropy will likely continue to increase. We're uncertain of the rate at which it'll increase, and it's always possible that funds raised will stall or decrease. Despite the economic downturn, our projections for funds raised among these donors haven't changed much. Our goal is to reach $500 million in funds raised from donors other than Open Philanthropy by 2025. We think this goal is ambitious but plausibly achievable with effort.

- The level of funding we'll receive from Open Philanthropy in the future is very uncertain. There is a wide range of possibilities, but our median expectation is that funds from Open Philanthropy will taper down from a high of $350 million in 2022.

- Previously, Open Philanthropy had tentatively planned to give $500 million in each of 2022 and 2023. We projected that level of funding out to 2025 as a best guess. In early 2022, Open Philanthropy revised its plans to give $350 million in 2022; it tentatively plans to give $250 million in 2023. Our best guess is that Open Philanthropy's funding will continue to decrease.

- Open Philanthropy's future plans have been affected by a decrease in their available assets as well as by a reconsideration of how to allocate funding across causes (e.g. longtermism vs. global health & wellbeing), which is still in progress. In conversation, Open Philanthropy confirmed that its confidence in GiveWell's research hasn't changed.

The charts below show our current forecasts of different funding scenarios.

Total funds raised in millions of dollars, 80% confidence interval[3]

(same chart as in the summary above)

Funds raised excluding Open Philanthropy in millions of dollars, 80% confidence interval[4][5]

How will we respond to shifting funding expectations?

-

Continued focus on finding outstanding giving opportunities. This isn't a change, but we're highlighting our focus on finding outstanding giving opportunities because it remains a priority despite uncertainty about total funds raised. We're expanding our team so that we can improve and scale up our recommendations. Over the past couple of years, we've scaled up support to our top charities and made grants to several programs that are new to us, and we expect to continue to do so. (See here for a database of grants we've made.) When we first adjusted our funding expectations downward in 2022, we raised our cost-effectiveness bar from 6x cash to 10x cash in order to ensure we're fully funding the most cost-effective opportunities we identify.

Whether our funds raised are closer to $300 million or $1 billion in 2025, that's still much higher than they were 5 years ago and makes GiveWell one of the world’s largest private funders of global health. Our research team hasn't yet fully grown to meet GiveWell's scale as a funder raising hundreds of millions of dollars annually; there are many more research projects we'd like to be taking on. -

Potentially smoothed spending from year to year. We want to position ourselves well despite uncertainty and avoid dramatic changes in our cost-effectiveness bar (currently, 10x cash). We'll revisit our cost-effectiveness bar as we get more information about the funds and opportunities available to us. We'll adjust it if needed, but we don't currently have plans to change it. If we expect funds raised to decline from one year to the next, we would hold back some funding in order to maintain a stable cost-effectiveness bar.

It's higher impact to spend at e.g. 10x two years in a row than to spend at 8x one year, only to be unable to fill 10x gaps the next year. And, it helps us set appropriate expectations with the organizations we might fund – we don't want them to invest in scoping or scaling up new opportunities only for our cost-effectiveness bar to change.

More generally, we don't intend to hold onto large amounts of funding indefinitely, but we also don't think it's inherently bad to carry some funding from one year into the next if it helps maximize the impact of those dollars. -

Increased fundraising efforts. We've expanded our outreach team and will be focusing on retaining our existing donors and bringing in new donors, especially those who can give at an extremely high level. Successful fundraising will enable us to grow in the long-term regardless of any single donor's funding decisions and will provide the funding needed to fill all of the most cost-effective gaps we find.

Our best guesses are very uncertain

In late 2021, we don't think we sufficiently accounted for uncertainty either internally or in our public blog post (which didn't substantially discuss uncertainty, instead just sharing a single point estimate). We've since learned from that experience.

We currently think there's a 50% chance that we'll raise between $400 million and $800 million in 2025, with roughly equal chances of landing above or below that range. We could still be wrong about how confident to be in these estimates, and the true probability of funds raised falling in that range could be more or less than 50%. We wouldn't be shocked if we managed to raise much more than $800 million, or if circumstances led to us raising less than $400 million.

Going forward, we'll continue to regularly update our projections of funds raised and funding opportunities identified so that we can adjust our spending to maximize the impact of our funding overall. If we need to adjust our cost-effectiveness bar, we'll plan to do so gradually.

We'll share public updates if there are important changes to our forecasts or our plans.

And regardless of exactly how the future unfolds, we aim to expand our research team and allocate additional resources to cost-effective programs – so please consider applying or donating!

Notes

This chart, which we also discuss later in the post, is intended to give a general sense of possibilities. The overall shape seems approximately right to us, but the exact numbers are very uncertain. ↩︎

Note that "funds directed," which we discussed in the 2021 blog post, is different from "funds raised" in a given year, which is the focus of this blog post. "Funds raised" is simpler to forecast because it doesn't involve estimating the timing of grant decisions or when certain types of funding become available. ↩︎

This table gives the underlying data for this chart. These figures aren't intended to be as precise as the number of significant figures might imply. We're using this model to get a general sense of possibilities, and we're using rough estimates and simplifying assumptions that mean it's not entirely accurate.

↩︎

The dip from 2021 to 2022 is due to a combination of (a) a one-off donation of around $50 million from Vitalik Buterin in 2021 and (b) a change in how we're measuring funds raised to exclude the (historically substantial) amount of funding given to GiveDirectly as a result of our recommendation, due to this change to our top charities list. Without those two things, we estimate that funds raised would have increased from 2021 to 2022. 2022 figures are not yet final. ↩︎

This table gives the underlying data for this chart. These figures aren't intended to be as precise as the number of significant figures might imply. We're using this model to get a general sense of possibilities, and we're using rough estimates and simplifying assumptions that mean it's not entirely accurate.

↩︎

Hi Robi, thanks for the question! This is Isabel Arjmand from GiveWell – I wrote the above post, and I run the model we use to forecast funds raised.

The uncertainty primarily stems from the fact that Open Philanthropy is in the process of reconsidering how it allocates funding across cause areas.

We’ve spoken with Open Philanthropy about their plans, and our understanding is that the amount of funding Open Philanthropy might give to GiveWell in the future is highly uncertain at this point. Our impression is that it could be hundreds of millions of dollars annually or could be very little. While the funding we may receive from Open Philanthropy in the future is uncertain, Open Philanthropy confirmed in conversation with us that its confidence in GiveWell’s research hasn’t changed.

Based on our qualitative impressions of the uncertainty and of the range of plausible outcomes, we created a quantitative model for what Open Philanthropy might give in the future, which is what feeds into our forecasts.

We expect to know more later this year once Open Philanthropy has wrapped up this project.

Please let us know if you have any more questions!