TL;DR: Two different approaches for classifying projects or causes as “longtermist” clash significantly, which leads to oversimplifications of “longtermism” and causes people to pursue less impactful projects. I list some tentative suggestions at the end.

Notes: I discuss whether or not different projects are "longtermist" a lot in this post, but I don't want to imply that I think there's a very strong benefit to making sure that a project fits neatly in this group. For instance, I’m not arguing that people should be (or are) more “hardcore” with respect to longtermism, or anything like that. And if a project looks promising under multiple plausible worldviews, that should probably be considered a benefit (related, and also related).

Finally, arguments in this earlier post probably still inform my thinking on all of this.[1]

What is a “longtermist project”?

- One way of classifying something as “longtermist” is based on the definition of the philosophy/belief set. Under this approach:

- A given project is “longtermist” (or not) depending on whether its primary purpose is to have an impact via influencing the long-term future — or at least if it looks good from a longtermist worldview. Not necessarily depending on whether it’s in biosecurity, animal welfare, AI, or whatever else. [3]

- Alternatively, we could say that there are clusters of work (or causes) that are called longtermist — for historical reasons and because people who take a “longtermist” perspective often endorse working in these areas.[4] In this view:

- Biosecurity, AI safety, reducing the risk of global conflict, etc. are “longtermist causes.” Extinction risk reduction generally falls under this, but also anything that looks like “reduce the risks of a catastrophic event,” even if the people pursuing the project are just hoping to prevent catastrophes from harming beings who are alive today.

I’m sure there are other approaches to this classification, but I’ll focus on these two.

These two approaches don’t always agree on what is “longtermist”

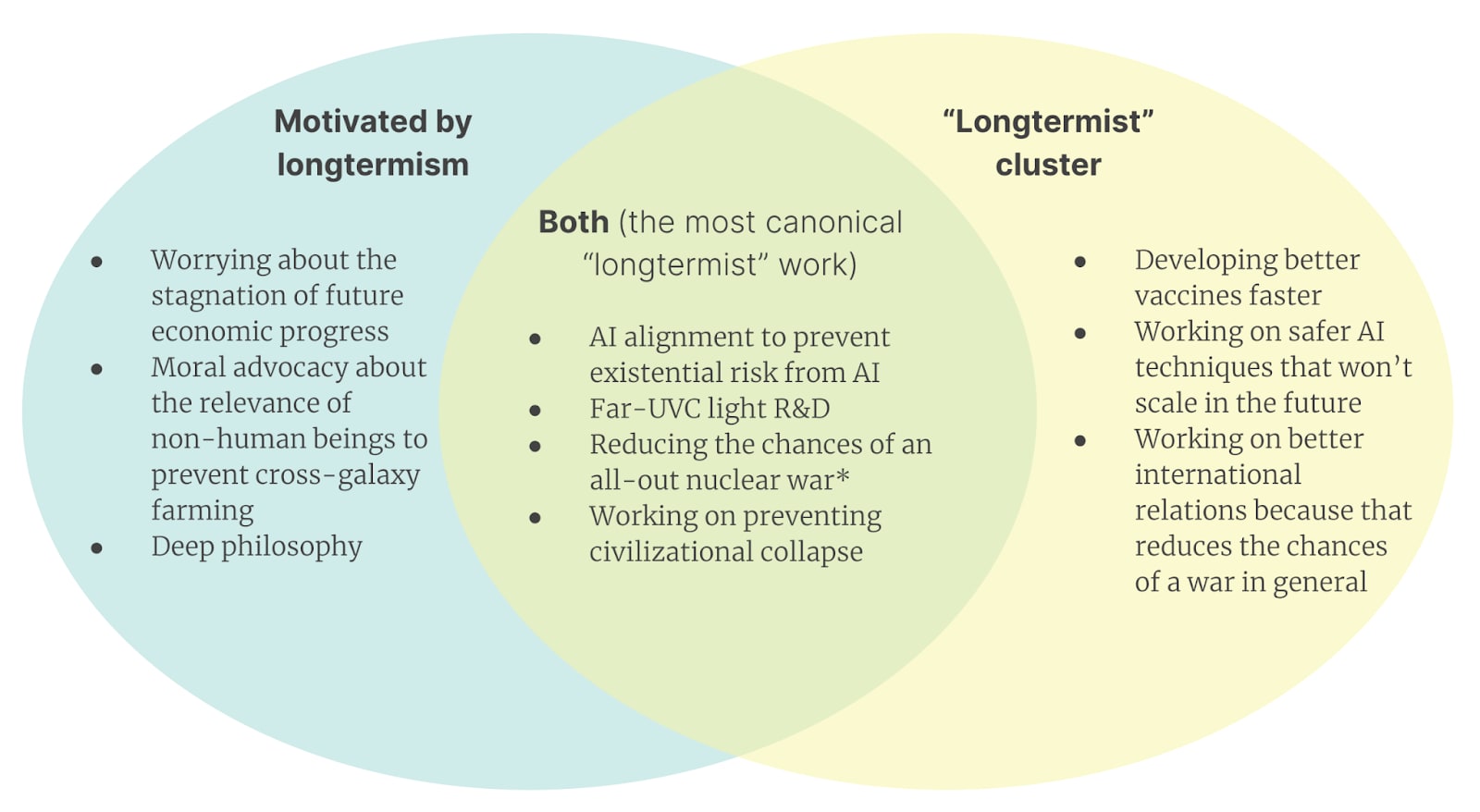

Below is a rough Venn diagram of some types of work that are called “longtermist” in one or both of the approaches (note that I didn’t try to classify things very carefully, or try to be exhaustive).

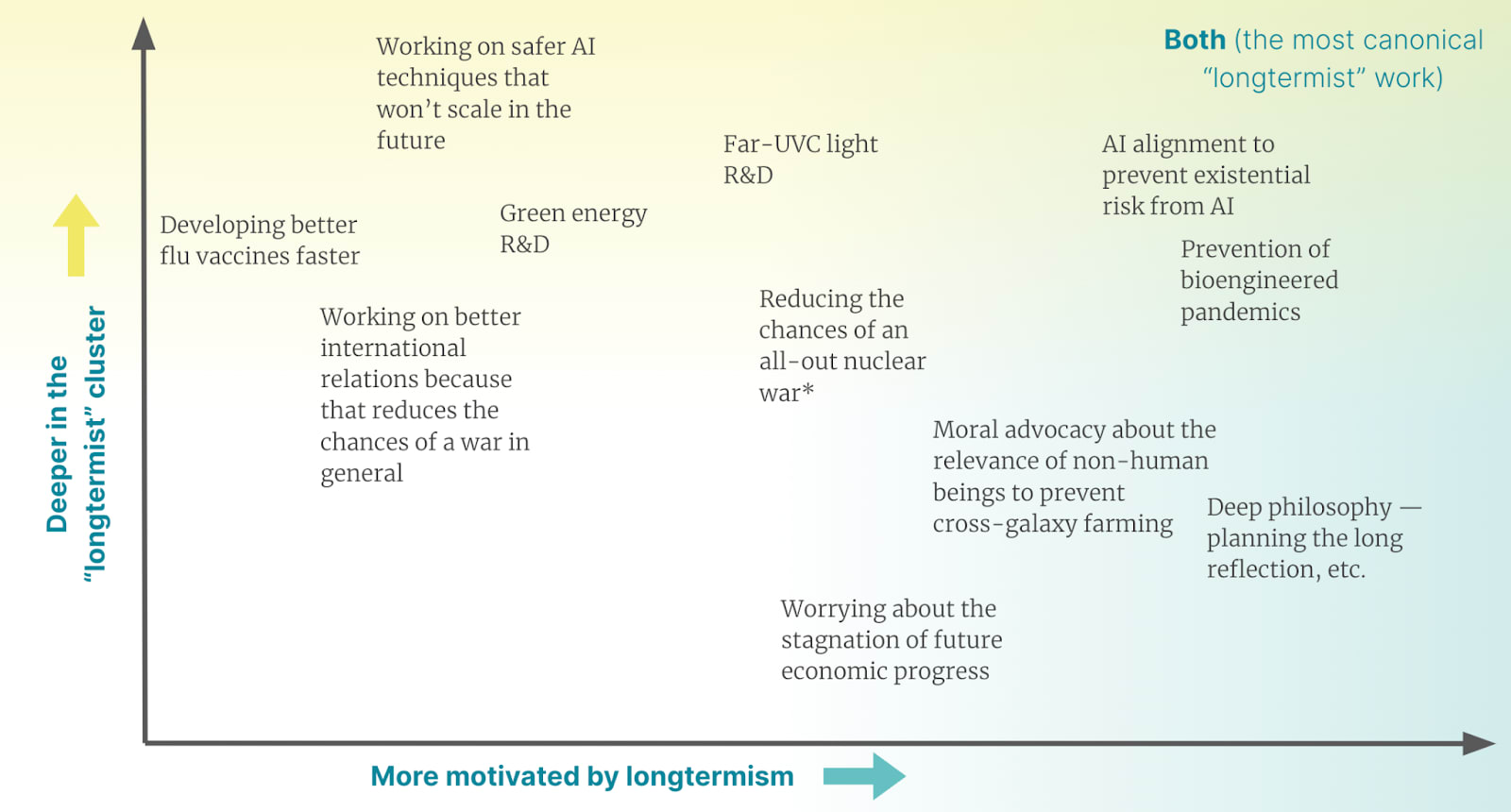

Many of the relevant distinctions aren’t binaries, but rather spectrums — some things look more or less “longtermist” under one of the two approaches, as opposed to simply being clearly “longtermist” or not — so a better picture might look more like a 2-dimensional visualization:

In this diagram, the most canonical “longtermist” projects are in the top-right corner; the examples I chose are in the “longtermist cluster” and are often directly motivated by longtermism. This includes AI alignment, prevention of bioengineered pandemics, etc. Developing better flu vaccines is often associated with longtermism through biosecurity — an ostensibly “longtermist” cause — while advocacy or research about the moral relevance of non-human beings can be deeply motivated by longtermism but often isn’t thought of as “longtermist” because it’s not clearly in the cluster.

Note that some people believe that basically no projects outside the canonical longtermist ones actually look promising under a longtermist worldview (although they might agree that the "longtermist cluster" contains things that also aren't "longtermist" under this classification). I currently disagree, but can see this point of view.

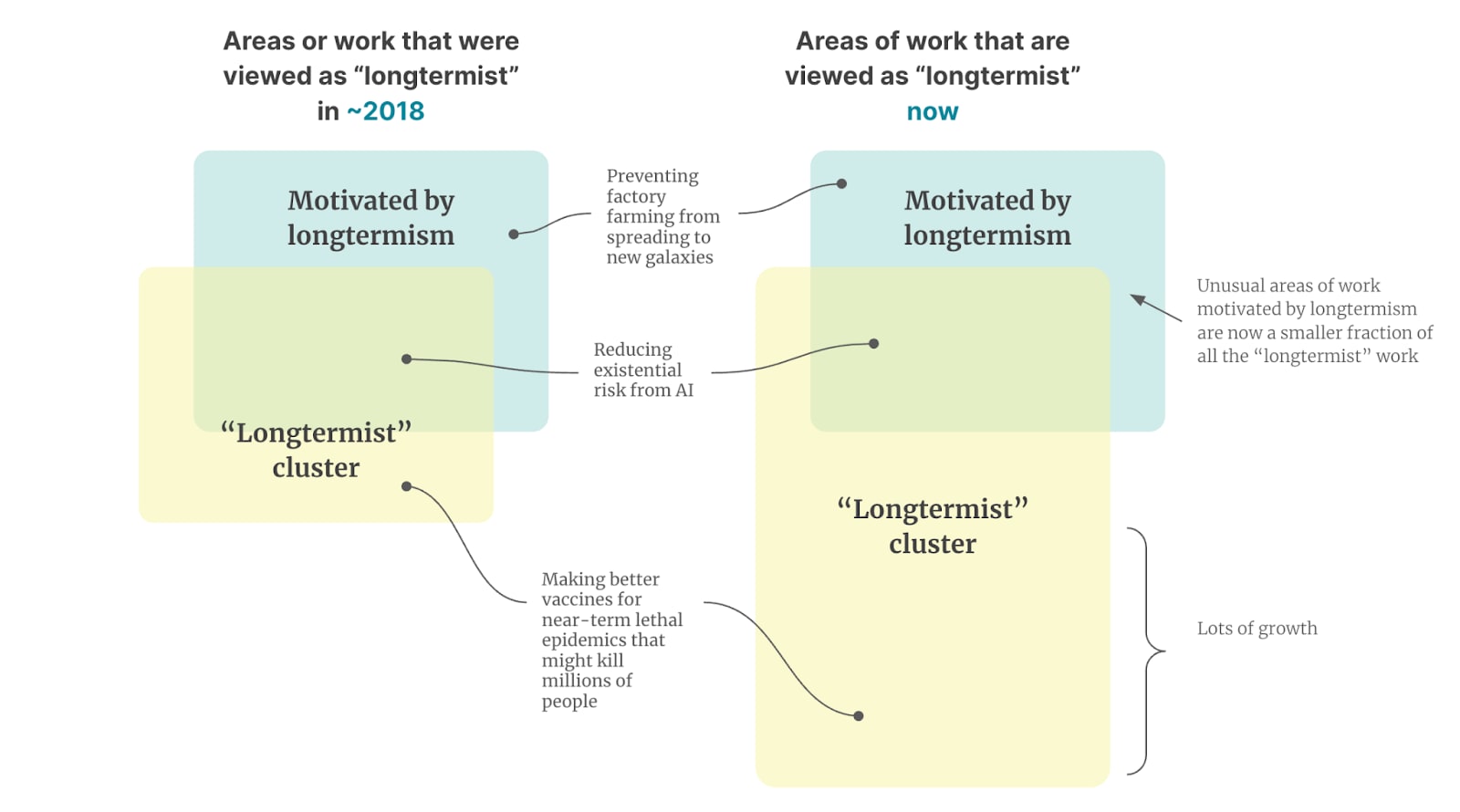

The difference between the two approaches is growing, and people who primarily think about the “longtermist cluster” now identify “longtermism” more closely with the causes it is currently associated with (AI safety, biosecurity, general risk reduction)

I think the two approaches have been different for a while (e.g. a lot of work on biosecurity is not motivated by longtermist thinking).

And the approaches have diverged more recently. Some of the causes previously dominated by “longtermists”[5] have grown a lot — more people have started to believe these causes are pressing problems and have started working on them (particularly AI risk and pandemic preparedness). These areas remain coded as “longtermist,” but many of the people working in them today are not significantly motivated by the desire to improve the long-term future. Relatedly, some risks that many believed were “long-term future risks” are now more widely viewed as urgent or near-term, so more people have started working on them for different reasons (there’s a convergence going on, to some extent; people with different values now share more priorities in practice). (See for instance this piece by Scott Alexander.)

Some resulting problems

We assume someone’s philosophy based on their “revealed cause prioritization” and vice versa — which causes further difficulties

Examples of this kind of thing going wrong (some of these are very similar to things I've seen or heard about):

- Pluto says that they agree with the classic longtermist argument, so the people talking to Pluto (and, say, recommending opportunities to Pluto) assume that Pluto wouldn’t work on non-human welfare and don’t recommend those opportunities to them

- Or even just assume that Pluto wants to work on AI safety

- Ariel is working on AI safety, so people assume that she fully endorses longtermism or makes all cause-prioritization decisions based on longtermism (slightly related[6])

- ...which could additionally cause information cascades or incorrect deferral to Ariel in a way that causes more people to take on a kind of naive and more “hardcore” longtermist perspective on the world

- Eve doesn't buy the longtermist argument and gets frustrated because she sees prominent members of the community endorsing projects that are in the longtermist cluster a lot, which leads her to conclude that these people believe that longtermism is the only viable approach

- You see that Gascon is working on AI safety, so you assume that he cares about the long-term future and entrust him with something like a grantmaking project aims to improve the long-term future — but actually Gascon just finds his current AI safety project interesting, or thinks that AI is a near-term harm

- You meet Baymax, who works on biosecurity (say, far-UVC light), and you disagree with the longtermist argument. You start talking about cause prioritization and you feel like you can try to convince Baymax of all your reasons for not believing the longtermist case. This is not useful; Baymax's main crux for prioritizing biosecurity is the potential for near-term pandemic harm.

People motivated by longtermism might overlook unusual areas of work or go for something that’s in the “longtermist cluster” but isn’t actually that promising when considered from a philosophically longtermist perspective

- When someone is seriously compelled by the longtermist argument, they might simply not consider areas like animal welfare, because they don’t see many discussions of animal welfare and longtermism; most “longtermist” spaces are full of discussions from the “longtermist cluster.”

- If someone gets classified as “longtermist” or agrees with the classic argument and wants to do “longtermist work,” they might default to things in the “longtermist cluster” without prioritizing within that cluster enough. So they might e.g. do work that’s much more relevant for near-term epidemic preparedness than work that really helps in cases like global pandemics or non-bio work.

- I have similar concerns about “EA projects” sometimes.

Semi-related: people who disagree with the classic longtermist argument might steer away from “longtermist”-coded projects despite them actually looking good under other philosophical and empirical worldviews

I think some projects are promising under non-”longtermist” worldviews, but get somewhat overlooked by people who don’t think longtermism is sound as a philosophy. For example:

- Near-term AI safety work

- Studying ways to improve international coordination to reduce the chances of war or conflict (because that would be bad for people alive today)

- Developing vaccines for potential pandemics faster, developing cheaper and more accessible PPE, etc.

- Reducing extinction risk because extinction is bad under completely different worldviews

I’m not sure how much this happens, in practice.

A few (tentative) suggestions/takeaways

I'm not sure about these!

- Avoid implying that some project is only justified based on a pretty narrow philosophy/worldview (e.g. longtermism) unless you’re pretty sure that’s the case.

- I think generally “longtermist or not” is a worldview distinction that’s over-used in EA; e.g. human-focused vs. not is probably at least as important, as are more empirical questions like “do you believe that very powerful AI systems are coming soon?” I expect that it’s often more useful to group things based on other questions/classifications (instead of whether or not they’re “longtermist”).

- When you do talk about whether something is “longtermist” or not, specify what your approach is and make that clear. (E.g. this was a useful conversation.)

- I generally try to reserve the label “longtermist” for projects that are in fact motivated by longtermism (although at this point I also think it makes sense to use it to identify a cluster of work in our broader network).

- Notice if you’re making assumptions about someone’s worldview based on something like the cluster they seem to be in (and vice versa), and check whether you endorse having this as a very strong prior.

- Consider more often avoiding the term “longtermism” if you’re not really sure what you mean by it and how others will understand it.

- ^

I initially wrote a version of the current post over a year ago. In it, I mostly argued for a specific classification system (the motivation-based system below). I never ended up posting it because I wasn't convinced of my arguments, but related topics have come up many times since then and I've decided to try sharing something. I'm still not totally convinced of the details.

Relatedly, I think the arguments here are not particularly new, but I don't remember seeing someone lay them out in one place.

- ^

You can also try to define projects as “longtermist” depending on where their actual impact lies, as opposed to the motivations of the people pursuing the project. I think this is more difficult but will result in a similar approach (although different conclusions). (I haven't checked carefully.)

- ^

These projects can also look good under other philosophical/moral approaches — I’m not claiming that longtermism has to be the only reason for pursuing some kind of work.

- ^

The cluster is also probably associated with requiring a higher willingness to work on low-probability events, longer feedback loops, etc. — things not necessarily relevant to the philosophy directly.

- ^

which are therefore in the “longtermist cluster” for historical reasons

- ^

Holden Karnofsky: There’s a line that you’ve probably heard before that is something like, “Most of the people we can help are in future generations, and there are so many people in future generations that that kind of just ends the conversation about how to do the most good — that it’s clearly and astronomically the case that focusing on future generations dominates all ethical considerations, or at least dominates all considerations of how to do the most good with your philanthropy or your career.” I kind of think of this as philosophical longtermism or philosophy-first longtermism. It kind of feels like you’ve ended the argument after you’ve pointed to the number of people in future generations.

And we can get to this a bit later in the interview — I don’t think it’s a garbage view; I give some credence to it, I take it somewhat seriously, and I think it’s underrated by the world as a whole. But I would say that I give a minority of my moral parliament thinking this way. I would say that more of me than not thinks that’s not really the right way to think about doing good; that’s not really the right way to think about ethics — and I don’t think we can trust these numbers enough to feel that it’s such a blowout.

And the reason that I’m currently focused on what’s classically considered “longtermist causes,” especially AI, is that I believe the risks are imminent and real enough that, even with much less aggressive valuations of the future, they are competitive, or perhaps the best thing to work on.

Thank you, Lizka, for this post. I focus on pandemic preparedness, and I had assumed that biosecurity was primarily a “longtermist” cause. I felt uncomfortable not having a settled personal view on longtermism as a philosophy. Reading your post and the linked references reassured me that it is fine not to claim longtermism as my motivation. I still want to learn more about moral philosophy to eventually form my own view on longtermism, but in the meantime I now think it is reasonable to say that I share the goals and the drive to contribute, even if my reasons do not fully align with those of longtermists. David Thorstad’s series also gave me some food for thought: https://reflectivealtruism.com/2023/11/18/exaggerating-the-risks-part-12-millett-and-snyder-beattie-on-biorisk/ - Do you know of any circulated survey that gives insights into what motivates EAs to work on this or that cause/intervention (i.e longtermist worldview or not)?

I like this framing, and I found that is resonates well with a minor level of discomfort I've had about uses of the term "longtermism." I especially liked the examples you have with characters (Pluto, Eve, etc.), as I find a few examples for a concept/framework to be very helping for grasping the "shape" of the idea.

Separately, I really like the graphics that you made for this. I think that you designed them well, from the color choices to the spacing. Could you share what tool/program you used to create these graphics?

Thank you! I used Google Slides. :)

Wow! I've never seen such nice design from Google Slides. Great job.