Crosspost of this article.

1 Forethought

You hear a lot of talk about AI alignment, the process of getting AI’s aims to line up with our own. This makes sense given that we’re currently in the process of building AIs that could be vastly smarter than people, and we don’t yet have a great plan for getting them to do what we want. Surprisingly, there isn’t as much talk about other kinds of AI preparedness. If we’re creating superintelligence, this will have a profoundly transformative impact on every aspect of our world, and it’s best to prepare.

Enter Forethought. They’re a research organization trying to figure out how to navigate a world of profoundly transformative AI. They have some extremely impressive people on the team, including Will MacAskill (one of the cofounders of effective altruism), Tom Davidson (formerly a senior research fellow at Open Philanthropy), and many others. Hopefully they will also hire me!

A while ago, Forethought published a report called Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion. I thought the report was thoughtful, cogent, and persuasive. Its core thesis is probably right, and it has huge implications if it is right. For this reason, it seemed like a good idea to summarize it. That’s what I’ll do here. I won’t say, every sentence, “the Forethought team says,” but just know, I’m primarily summarizing what they say, not giving my own thoughts.

Their thesis in a nutshell: AI is likely to radically transform the world, prompting staggeringly fast economic growth, many new technologies, and a number of unprecedented challenges. And the world isn’t ready.

2 The intelligence explosion

TLDR: AI is advancing very rapidly and shows no sign of stopping. Among other things, the number of AI models we can run is increasing 25x per year, 500X as fast as growth in number of human researchers. If this continues, we will get extremely rapid growth in research abilities, which will prompt unprecedented innovation—potentially hundreds of years of growth in a few years even on conservative assumptions that predict pretty dramatic slowdowns in AI capabilities growth. Advancements in research capabilities will lead to both a technological and industrial explosion.

The fine print…

Every year, human research capacity grows about 5% per year. In contrast the number of AI researchers we can create has been growing 25x per year, over 500 times as quickly. Research is the primary bottleneck to long-term economic growth. These trends are on track to continue for quite a while. Once AI reaches human capabilities, therefore, it will be as if the number of researchers is growing 25x per year. So even if AI progress slowed down considerably (say, to only growing 4x per year) and never advanced past human capabilities, we’d be on track for explosive growth of a kind never before seen in history.

New innovation can figure out new clever ways to overcome bottlenecks. So if AI continues growing this quickly—or even if it slows down considerably but not completely—we’re in for a massive explosion of economic growth and technological progress.

The trends driving rapid AI progress are:

- Training compute: this is the amount of raw computational power that goes into training the AI models. It’s been growing about 4.5x per year since 2010.

- Algorithmic efficiency in training: this is how efficiently the algorithms use computational power. Efficiency has been growing 3x per year (from 2012 to 2023). This, combined with the last factor, has been leading to effective compute from pretraining going up by more than 10x per year.

- Post-training enhancements: this is the improvements in AI capabilities added after training, and it’s been growing about 3x per year, according to Anthropic’s estimates. Combined with the more than 10x boost in algorithmic efficiency, “it’s as if physical training compute is scaling more than 30x per year.”

- Inference efficiency: this is how cheaply you can run a model at a given level of efficiency. This cost has been dropping 10x per year, on average, since 2022.

- Inference compute scaling: This is the amount of physical hardware going into model inference, and it’s been going up 2.5x per year since 2022. In total, then, these two factors, if they continue, could support a growth in the AI population of 25x per year. And both are on track to continue for quite a while.

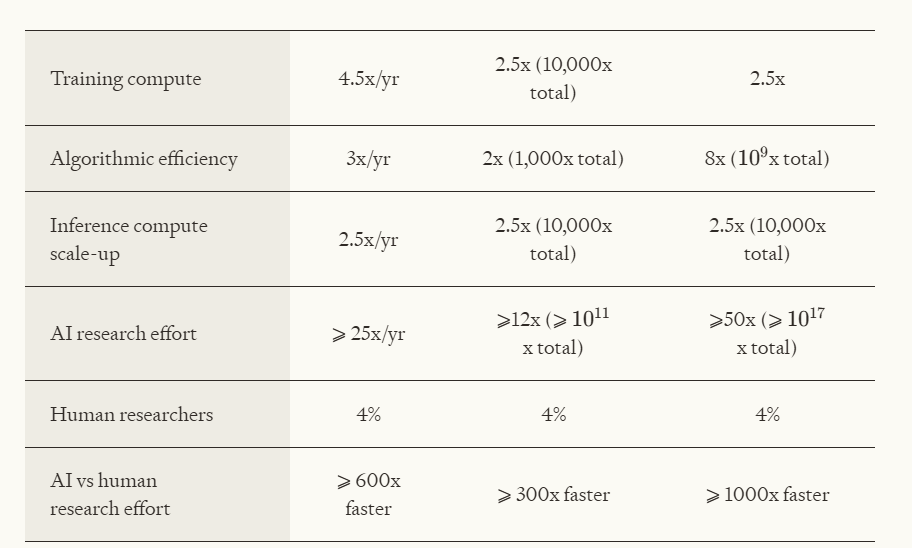

The chart below shows how rapid progress could be (showing both yearly growth rates and growth rates over the course of a decade):

The authors write “Putting this all together, we can conclude that even if current rates of AI progress slow by a factor of 100x compared to current trends, total cognitive research labour (the combined efforts from humans and AI) will still grow far more rapidly than before.”

AI research capacities are improving dramatically. On Ph.D level science questions, GPT-4 at the beginning performed only slightly better than random guesswork. 18 months later it beat Ph.D level experts. AI’s main bottleneck has been its inability to perform long and complex tasks, but possible task length has been doubling roughly once every seven months. If this keeps up, AI will, in a few years, be able to quickly perform tasks that take expert humans up to a month, then several months, then years, then decades.

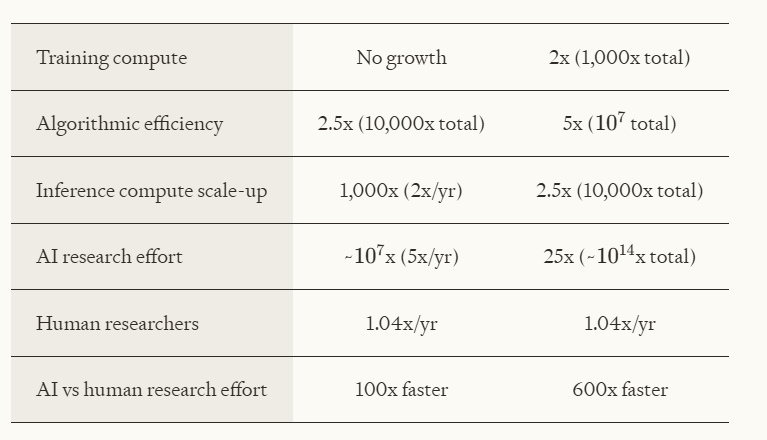

After AI reaches parity with humans, it won’t just stop. Even relying on very conservative estimates of the growth in AI capabilities, it will shoot far past humans. The chart below shows that even on very conservative assumptions, AI research capabilities will grow 100 times as quickly as human research capabilities in the decade after AI reaches parity with humans.

All this illustrates that the case for explosive growth in research capabilities is pretty robust. Even if there’s stagnation in some areas, progress in other areas could fill the void. Several different kinds of stagnation would be needed for AI to stagnate overall. In Forethought’s conservative estimate of research progress, total research capabilities would go up about 5x per year, leading to overall research capabilities growing 10 million times in a decade. “This would be enough to drive over three hundred years’ worth of technological development on current rates of progress.”

The big thing you hear from AI progress skeptics is that we might hit a wall in these metrics, especially scaling. After all, as Toby Ord notes “increasing the accuracy of the model’s outputs [linearly] requires exponentially more compute.” This is certainly a possible bottleneck, but now I’d bet that AI progress will continue for quite a while. Before I give the specific arguments, let me give the one sentence synopsis that you should hold in your head when thinking through claims that AI is hitting a wall: for AI to be plateauing, several different consistent trends that have been roughly constant for many years would have to slow down very dramatically—even if they merely slowed down by 90%, you’d still get an intelligence explosion.

Now for the details:

- The trends are fairly robust. The most important trends for continued progress are compute and algorithmic efficiency, but both have been going up for many years. One should always be skeptical of claims that a persistent trend will stop. In particular, there seems to be no strong evidence that algorithmic efficiency has slowed, it’s been going up about 3x per year for about a decade, and it alone continuing would be enough to drive rapid progress. If scaling hits a wall, we should expect more investment in algorithmic improvements.

- In addition, despite recent hype, pretrain compute has been going up about 4.5x per year and doesn’t look to be on track to stop. Progress from scaling is likely to continue till at least 2030.

- As the charts show above, even if there was pretty considerable slowdown on some trends, economic growth could still be amazingly fast. Even if the number of AI models merely doubled every year after reaching human-level capabilities, that would still be like the population of researchers doubling every single year.

- There’s good reason to think AGI is possible in principle. Billions of dollars are being poured into it, and the trend lines look pretty good. These facts make me hesitant to bet against continued progress.

- As we’ve seen, progress in algorithmic efficiency has been pretty robust. This allows continued growth even if scaling hits a wall. Scaling alone has been a driver of lots of progress, but even if pure scaling is inadequate, progress can continue. Despite some slowdowns in pretrain compute, benchmark performance is still on trend, partially driven by boost in reinforcement learning.

- AIs are currently very useful. However, they are very inefficient at learning compared to humans. This should lead us to suspect that there is lots of room for possible improvement in AI’s ability to learn. Even small improvements in this could lead to extreme progress.

And note: this doesn’t rely on recursive self-improvement. It just relies on capabilities being multiplicative and continuing to go up according to anything like current trends. If you think AI will self-improve, you get even faster growth. And this feedback loop isn’t unlikely because doubled research efforts tend to lead to more than doubled software performance, so even accounting for new software innovation getting harder to find, there’s still reasonable chance of a feedback loop (Tom Davidson guesses there’s a 50% chance of a software feedback loop).

Now, total economic growth is significantly bottlenecked by physical labor. Tons of research isn’t enough unless you can build and experiment. But cognitive labor would still be able to make many different kinds of important innovations, leading to massive progress in non-labor-intensive industries like mathematics. In addition, very intelligent AI would be able to use the comparatively constrained physical labor optimally, and perform robust simulations to fill in for the physical bottleneck.

So stage one of the intelligence explosion is a software explosion. AI capabilities would accelerate massively, along with broader progress in fields constrained by the numbers of researchers.

We should also expect this software explosion to produce a technology explosion. Advancements in research will be so rapid that even accounting for declining returns and taking a conservative estimate of the speed of software improvement, we’d be on track for 300 years of technological growth in a decade.

This massive growth in innovation could lead to huge increases in robotic technology. This creates feedback loops—robots could build more robots designed to build more robots, leading to even faster progress. And as algorithms advance extremely quickly, we should expect to see advancements in the algorithms behind robots, leading to even more efficient operationalization. This massive technological progress will lead to a huge upswing in industrial capabilities. Production will increase dramatically.

Thus, unless things slow down dramatically on several different metrics, we are in for a wild ride, the likes of which have never been seen before in human history. Planning for such an insane world seems important. Thus, my guess: 60% odds that at some point in the next few decades, we’ll see a century’s worth of growth in a single decade. And potentially things could go significantly faster. 100 years of growth in a decade is a pretty low-end estimate.

3 After the explosion

Suppose we get this explosion in software, technology, and/or industrial power. This will lead to huge advances in many different domains and to many new challenges. The last century brought about new threats, with the discovery of Fascism, bioweapons, and the nuclear bomb. Now imagine compressing all those discoveries into ten years. That’s what we’re likely in for.

One point that strikes me as very clear: we should have more smart people thinking these things through. That’s one reason why I think donating to Forethought is a good bet (though conflict of interest alert: I directly benefit from Forethought having more money as it means they’ll hire more people, thus making it likelier they’ll hire me). You can see some of the impact they’ve had so far here. To me it seems clear that in a world where there’s basically only one group on the planet thinking through non-alignment aspects of the intelligence explosion, funding them is a good idea.

But let’s survey the big challenges posed by an intelligence explosion. I’ll bold the things that are my ideas but don’t appear in the paper.

3.1 AI takeover

Extremely rapid advancements in AI raise the odds that AI will takeover. AI might become misaligned, in the sense that we don’t successfully get it to do what we want. This misaligned AI, once it achieves superintelligence, could take over. To prevent these risks we should fund alignment research including:

- Interpretability research which gives us greater insight into what the AI is thinking.

- Research on using reinforcement learning to get the AIs not to do bad things (e.g. by being risk averse).

- Research to stop AI alignment faking.

- Research to stop AIs from resisting shutdown.

The authors don’t discuss alignment much in the report because it’s been discussed extensively elsewhere. But this is clearly an important thing to get right.

3.2 Very destructive technologies

If the AI produces extremely rapid economic growth, we should expect it to produce many new technologies. If the last century’s technological progress had been compressed into a decade, we’d have gotten nuclear weapons, drones, biological weapons, cyber warfare, and much more in less than a decade. Future potentially destructive technologies include:

- New more virulent bioweapons.

- Huge drone swarms. Dangerous drones could be mass-produced cheaply and in secret given that “One deadly, autonomous, insect-sized drone for each person on Earth could fit inside a single large aircraft hangar.”

- Enormous nuclear stockpiles, large enough to threaten human extinction, unlike current nuclear stockpiles.

- Atomically precise manufacturing that could allow one to 3-D print nearly any technology.

- Effective missile defense that enables countries to safely launch nuclear first-strikes.

- Other. This probably is the biggest risk, aside from bioweapons. We should expect that a lot of future technology will be unpredicable, just as people in 1920 wouldn’t have been able to forecast very well the technology of the last 100 years.

To guard against these, we should:

- Use AI to create defensive technologies that can guard against potential risks from new tech.

- Develop international treaties that prevent the development of dangerous new technologies

- Heavily regulate whichever new technologies the AIs suggest could be used to threaten the world (e.g. the tech that could be used to build drones). Ideally we could have really smart and precise AI regulators.

- Slow the intelligence explosion, which could give the world more time to adapt to new technologies.

3.3 Power-concentrating mechanisms

The intelligence explosion could allow power to be concentrated in the hands of just a few actors. Whichever actors control the gains from AI could get access to extreme power. Risks from this include:

- AI might enable private actors to launch successful coups.

- Authoritarian countries might seize global control using AIs. They could create a singularly loyal and dedicated AI workforce to protect themselves.

- Explosive growth will benefit those who possess existing capital, leading to disproportionate future control from both individuals and countries with lots of wealth at the start of the intelligence explosion. This could also massively boost inequality.

To prevent these, we could:

- Impose regulations requiring AI model specs that prevent coups.

- Audit models for secret loyalties.

- Empower actors to prevent AI coups.

- Make AIs risk averse.

- Distribute capital more across people and countries. Alternatively increase its spread across good actors and reduce its spread across bad actors.

- Reduce the scope and spread of global authoritarianism.

Note: these suggestions aren’t comprehensive, but just a general overview. For more, I recommend the Forethought report on stopping AI coups.

3.4 Value lock-in mechanisms

The rapid advancements in technology could allow some actor to permanently lock in their values, so that the future can’t change what’s ultimately brought about. Ways of doing this include:

- Advancements in AI capabilities could enable efficient surveillance that allows authoritarian regimes to remain stable.

- AI could be trained with goals that then get propagated for the rest of history (this one strikes me as the most worrying).

- Advanced AI could enable binding commitments.

- Technological advancements could allow us to shape the desires of future humans via genetic engineering.

- With new tech challenges, the odds of a global government increase, and this might lock in goals long-term. If such a thing develops, there is a strong moral reason to reflect carefully on the global government’s constitution.

I find AI being given goals that then get locked in to be the biggest risk. There is a strong moral case for very careful reflection before we give goals to extremely powerful AI.

3.5 AI agents and digital minds

AIs will get increasingly advanced and agent-like. It is very plausible that they will then become conscious. Given the massive scale-up in technological power, our actions might affect—either beneficially or detrimentally—the welfare of staggeringly large numbers of digital minds. This poses a number of challenges:

- We’ll have to decide which AIs merit moral concern. This will depend both on which factors make one morally important—whether consciousness, agency, or something else—and which digital minds have consciousness and agency (something notoriously hard to figure out).

- We’ll have to decide whether to give AIs rights and if so, which rights to give them. If AIs matter morally, probably we should give them rights. But given how easy it will be to create digital minds, if we give them the ability to influence the future, then we’ll quickly turn over global control to AIs.

- There’s risk that companies will train the AIs to say they’re not conscious, and people will thus ignore the AIs interests, just as we mostly ignore the interests of animals in factory farms.

- Even if we count interests of AIs, we might make moral errors, like promoting the wrong kind of welfare, failing to create well-off digital minds, or not believing there’s a moral reason to create happy people. We also might just not take moral pitches very seriously, and thus lose out on most future value.

- Even if we have mostly the right theory of consciousness, it might be a bit too broad or too narrow, leading to neglecting the welfare of many conscious beings.

To address these risks, we should:

- Allow digital people to have rights, so they’re not permanently disenfranchised.

- Impose welfare requirements for how digital minds are treated.

- Work to discover what makes AIs happy, and then make a bunch of happy digital minds.

3.6 Space development

Near-term space development sounds like science fiction. But if the arguments in section two are right, it is reasonably likely that we’ll get hundreds of years of progress compressed into decades. So if you thought without AI we’d probably get space colonization in the next few centuries, you should think with AI, we’ll probably get it within a few decades. This poses many challenges:

- Historically, countries have been able to consolidate power by taking over land. Similar dynamics are likely to hold in space. Whoever reaches space first may be able to hold on to power, but at a much grander scale.

- Once some entity gains access to space resources, it can use its resources to quickly expand operations throughout other star systems. Thus, the development of space may very quickly set off an uncontainable chain reaction.

These risks merit robust international agreements that will require the optimal use of space resources and prevent lone actors from taking over. Ideally, we’ll prevent anyone from grabbing resources in space until there’s a plan for making it go well. Similarly, I’d suggest imposing some tax so that some percent of space resources have to go towards creating happy digital minds.1

3.7 New competitive pressures

Very rapid growth in technology results in fierce competition with many serious downsides:

- There might be a race to the bottom. Whoever takes the fewest safety and welfare measures may have the biggest advantage. Thus, the most immoral risk takers may inherit the Earth (or the space, as it were).

- Competitive pressures might favor humans who hand over the most resources to AI systems. This could lead to rapid AI takeover.

- New AI technology could enable efficient blackmail—e.g. by threatening to unleash a bioweapon unless some course of action is taken.

There are also ways that the intelligence explosion could erode competitive pressures. For instance, impartial and cooperative AIs could be used to facilitate peaceful and desirable agreements.

3.8 Epistemic disruption

A technological explosion could disrupt our belief-forming process in major ways. Specifically:

- AI might be arbitrarily good at arguing, and thus always enable one to find capable arguments in support of one’s preexisting views. Changing minds might become harder.

- AI might have special persuasive abilities that allow it to convince people of things much more easily than people.

- AI might develop and spread ideologies that are viral but manifestly unreasonable.

- AI might discover destabilizing new truths that would disrupt how we think about the world. Just imagine discovering Newtonian physics, Darwinian evolution, all the evidence for Darwinian evolution, the big bang, all in a few years.

There are also some ways AI would be good for our collective belief-forming processes. It could:

- Enable rapid and efficient fact-checking.

- Enable fast and reasonable analysis of arguments.

- Make automated extremely accurate forecasts.

- Very intelligent AI could make better decisions than humans on matters of policy and other important decisions.

The last is already happening. If you have a controversial view, try arguing with LLMs about it. They make a pretty good devil’s advocate.

3.9 Abundance

The intelligence explosion could also have huge upsides. One of those is that it could produce unprecedented abundance. A world of rapidly growing wealth is one where everyone will be a lot richer. Advances in medicine, science, and consumer goods will follow. A richer world will tend to be more peaceful and careful, as those who are wealthier are less likely to go to war and more likely to try to extend their lives. It also opens up greater opportunities for trades across different value systems.

3.10 Unknown unknowns

It’s very hard to predict how the future will go. We just don’t know what technology will be available. As a result, we should expect a lot of crazy stuff to happen that we’d never guess.

4 Big takeaways

This has been a fairly scattershot presentation of their core ideas. Their paper is 61 pages, and I was trying to give a shortened summary. But what are the big ideas?

First, an intelligence explosion is (plausibly) coming. It is reasonably likely, though not certain, that we’ll get extremely rapid rates of economic growth of a kind never before seen in world history. We might be getting technology that looks like something out of science fiction.

Second, we can’t just punt every problem to the superintelligence. For some problems, we’ll need to get things right before we develop superintelligence (E.g. alignment). Additionally, once we reach superintelligence, it will be obvious who has power in the world, and so there is no longer as much opportunity for it to be in the interests of everyone to prevent any lone actor from taking control.

Third, there are a lot of challenges posed by the intelligence explosion. Misalignment isn’t the only threat. The world needs to prepare for the Pandora’s box of new risks—both technological and moral. There are many ways that the future could be destroyed or nearly all its value lost.

Fourth, there are many ways to prepare. We should:

- Give public servants the ability to use AI, so that they can consult it for important decisions.

- Think seriously about which values to give AI, rather than just how to get AI aligned with some values.

- Inform the world of the potential incoming intelligence explosion. Currently, few key decision makers are awake to what could be the greatest challenge of our times. That must change!

- Empower responsible decision-makers. I feel a lot better about a world where Anthropic wins the arms race than one where, say, Grok does.

- Impose regulations to slow the intelligence explosion and give the world time to prepare.

Navigating an intelligence explosion is an extremely difficult thing to do. There are lots of ways things could go wrong, but if things go well, the world could be made better beyond our wildest dreams. We are sleepwalking towards a cliff’s edge; it is time the world woke up.

This claim is not true:

If the trends over the last, say, five years in deep learning continued, say, for another ten years, that would not lead to AGI, let alone an intelligence explosion, and would not necessarily even lead to practical applications of AI that contribute significantly to economic growth.

There are several odd turns of logic in this post. For instance:

A fundamental weakness in deep learning/deep RL, namely data inefficiency/sample inefficiency, is reframed as "lots of room for possible improvement" and turned into an argument for AI capabilities optimism? Huh? This is a real judo move.

Overall, the argument is very sketchy and hand-wavy, invoking strange, vague ideas like: we should assume that trends that have existed in the past will continue to exist in the future (why?), if you look at trends, we’re moving toward AGI (why? how? in what way, exactly?), and even if trends don’t continue, progress will probably continue to happen anyway (how? why? on what timeline?).

There are also strange, weak arguments like this one:

Compelling virtual reality experiences are possible in principle. Billions of dollars have been invested in trying to make VR compelling — by Oculus/Meta, Apple, HTC, Valve, Sony, and others. So far, it hasn’t really panned out. VR remains very small compared to conventional gaming consoles or computing devices. So, being possible in principle and receiving a lot of investment are not particularly strong arguments for success.

VR is just one example. There are many others: cryptocurrencies/blockchain and autonomous vehicles are two examples where the technology is possible in principle and investment has been huge, but actual practical success has been quite tiny. (E.g., you can’t use cryptocurrency to buy practically anything and there isn’t a single popular decentralized app on the blockchain. Waymo has only deployed 2,000 vehicles and only plans to build 2,000 more vehicles in 2026.)

With claims this massive, we should have a very high bar for the evidence and reasoning being offered to support them. Perhaps a good analogy is claims of the supernatural. If someone claims to be able to read minds, foresee the future through precognition, or "remote view" physically distant locations with only their mind, we should apply a high standard of evidence for these claims. I’m thinking specifically of how James Randi applied strict scientific standards of testing for such claims — and offered a large cash reward to anyone who could pass the test. In a way, claims about imminent superintelligence and an intelligence explosion and so on are more consequential and more radical than the claim that humans are capable of clairovoyance or extrasensory perception. So, we should not accept flimsy arguments or evidence for these claims.

I wouldn’t even accept this kind of evidence or reasoning for a much more conservative and much less consequential claim, such as that VR will grow significantly in popularity over the next decade and VR companies are a good investment. So, why would I accept this for a claim that the end of the world as we know it — in one way or another — is most likely imminent? This doesn’t pass basic rationality/scientific thinking tests.

On the topic of Forethought’s work, or at least as Will MacAskill has presented it here on the forum, I find the idea of "AGI preparedness" very strange. Particularly the subtopic of space governance, which is briefly, indirectly touched on in this post. I don’t agree with the AGI alignment/safety view, but at least that view is self-consistent. If you don’t solve all the alignment/safety problems (and, depending on your view, the control problems as well), then the creation of AGI will almost certainly end badly. If you do solve all these problems, the creation of AGI will lead to these utopian effects like massively faster economic growth and progress in science and technology. So, solving these problems should be the priority. Okay, I don’t agree, but that is a self-consistent position to hold.

How is it self-consistent to hold the position that space governance should be a priority? Suppose you believe AGI will be invented in 10 years and will very quickly lead to this rapid acceleration in progress, such that a century of progress happens every decade. That means if you spent 10 years on space governance pre-AGI, in the post-AGI world, you would be able to accomplish all that work in just a year. Surely space governance is not such an urgent priority that it can’t wait an extra year to be figured out? 11 years vs. 10? And if you don’t trust AGI to figure out space governance or assist humans with figuring it out, isn’t that either a capabilities problem — which raises its own questions — or an alignment/safety problem, in which case, shouldn’t you be trying to figure that out now, instead of worrying about space governance?

Would it be any less strange if, instead of space governance, one of MacAskill’s priorities for AGI preparedness was, say, developing drought-resistant crops, or making electric vehicles more affordable, or reconciling quantum theory with general relativity, or copyright reform? Is space governance any less arbitrary than any of these other options, or a million more?

In my view, MacAskill has made a bad habit of spinning new ideas off of existing ones in a way that results in a particular failure mode. Longtermism was a spin-off of existential risk, and after about 8 years of thought and discussion on the topic, there isn’t a single compelling longtermist intervention that isn’t either 1) something to do with existential risk or 2) something that makes sense to do anyway for neartermist reasons (and that people are already trying to do to some extent, or even the fullest extent). Longtermism doesn’t offer any novel, actionable advice over and above the existential risk scholarship that preceded it — and the general tradition of long-term thinking that preceded that. MacAskill came up with longtermism while working at Oxford University, which is nearly 1,000 years old. (“You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?”)

AGI preparedness seems to be the same mistake again, except with regard to AGI alignment/safety and AI existential risk, specifically, rather than existential risk in general.

existential risk : longtermism :: AGI alignment/safety : AGI preparedness

It’s not clear what it would make sense for AGI preparedness to recommend over and above AGI alignment/safety, if anything. Once again, this is a new idea spun-off of an idea with a longer intellectual history, presented as actionable, and presented with a kind of urgency (yes, perhaps ironically, longtermism was presented with urgency), even though it’s hard to understand what about this new idea is actionable or practically important. Space governance is easy to pick on, but it seems like the same considerations that apply to space governance — it can safely be delayed or, if it can’t, that points to an AGI alignment/safety problem that should get the attention instead — apply to the other subtopics of AGI preparedness, except the ones that involve AGI alignment/safety.

Moral patienthood of AGIs is possibly the sole exception. That isn’t an AGI alignment/safety problem, and it isn’t something that can be safely delayed until after AGI is deployed for a year, because AGIs might already be enslaved, oppressed, imprisoned, tortured, killed, or whatever before that year is up. But in this case, rather than a whole broad category of AGI preparedness, we just need the single topic of AGI moral patienthood. Which is not a novel topic, and predates the founding of Forethought and MacAskill’s discussion of AGI preparedness.

Disclaimer: I have also applied to Forethought and won't comment on the post directly due to competing interests.

On space governance, you assume 2 scenarios:

I agree that early space governance work is plausibly not that important in those scenarios, but in what percentage of futures do you see us reaching one of these extremes? Capabilities allowing for rapid technological progress can be achieved under various scenarios related to alignment and control that are not at the extremes:

And capabilities allowing for rapid technological progress can be developed independently of capabilities allowing for the great wisdom to solve and reshape all our space governance problems. This independence of capabilities could happen under any of those scenarios:

So, under many scenarios, I don't expect AGI to just solve everything and reshape all our work on space governance. But even if it does reshape the governance, some space-related lock-ins remain binding even with AGI:

In all these scenarios, early space industrialisation and early high-ground positions create durable asymmetries that AGI cannot trivially smooth over. AGI cannot coordinate global actors instantly. Some of these lock-ins occur before or during the emergence of transformative AI. Therefore, early space-governance work affects the post-AGI strategic landscape and cannot simply be postponed without loss.

The disagreement could then be over whether we reach AGI in a world where space industrialisation has already begun creating irreversible power asymmetries. If a large scale asteroid mining industry or significant industry on the moon emerges before AGI, then a small group controlling this infrastructure could have a huge first mover advantage in using that infrastructure to take advantage of rapid technological progress to lock in their power forever/ take control of the long-term future through the creation of a primitive Dyson swarm or the creation of advanced space denial capabilities. So, if AI timelines are not as fast as many in this community think they are, and an intelligence explosion happens closer to 2060 than 2030, then space governance work right now is even more important.

Space governance is also totally not arbitrary and is an essential element of AGI preparedness. AGI will operate spacecraft, build infrastructure, and manage space-based sensors. Many catastrophic failure modes (post-AGI power grabs, orbital laser arrays, autonomous swarms, asteroid deflection misuse) require both AGI and space activity. If it turns out that conceptual breakthroughs don't come about and we need ridiculous amounts of energy/compute to train superintelligence, then space expansion is also a potential pathway to achieving superintelligence. Google is already working on Project Suncatcher to scale machine learning in space, and Elon Musk, who has launched 9000 Starlink satellites into Earth orbit, has also discussed the value of solar powered satellites for machine learning. All of this ongoing activity is linked to the development of AGI and locks in physical power imbalances post-AGI.

As I argued in my post yesterday, even without the close links between space governance and AGI, it isn't an arbitrary choice of problem. I think that if a global hegemony doesn't emerge soon after the development of ASI, then it will likely emerge in outer space through the use of AI or self-replication to create large scale space infrastructure (allowing massive energy generation and access to interstellar space). So, under many scenarios related to the development of AI, competition and conflict will continue into outer space, where the winner could set the long-term trajectory of human civilisation or the ongoing conflict could squander the resources of the galaxy. This makes space governance more important than drought-resistant crops.

All you have to admit for space governance to be exceptionally important is that some of these scenarios where AGI initiates rapid technological progress but doesn't reshape all governance are fairly likely.

This reply seems to confirm that my objection about space governance is correct. The only reasons to worry about space governance pre-AGI, if AGI is imminent, are a) safety/alignment/control problems or value lock-in problems, which I would lump in with safety/alignment/control and/or b) weaknesses in AI capabilities that either mean we don’t actually achieve AGI after all, or we develop something that maybe technically or practically counts as "AGI" — or something close enough — and is highly consequential but lacks some extremely important cognitive or intellectual capabilities, and isn’t human-level in every domain.

If either (a) or (b) are true, then this indicates the existence of fundamental problems or shortcomings with AI/AGI that will universally affect everything, not just affect outer space specifically. For instance, if space governance is locked-in, that implies a very, very large number of other things would be locked-in, too, many of which are far more consequential (at least in the near term, and maybe in the long term too) than outer space. Would authoritarianism be locked-in, indefinitely, in authoritarian countries? What about military power? Would systemic racism and sexism be locked-in? What about class disparities? What about philosophical and scientific ideas? What about competitive advantages and incumbent positions in every existing industry on Earth? What about all power, wealth, resources, advantages, ideas, laws, policies, structures, governments, biases, and so on?

The lock-in argument seems to imply that a certain class of problems or inequalities that exists pre-AGI will exist post-AGI forever, and in a sense significantly worsen, not just in the domain of outer space but in many other domains, perhaps every domain. This would be a horrible outcome. I don’t see why the solution should be to solve all these problems and inequalities within the next 10 years (or whatever it is) before AGI since that seems unrealistic. If we need to prepare a perfect world before AGI because AGI will lock in all our problems forever, then AGI seems like a horrible thing, and it seems like we should focus on that, rather than rushing to try to perfect the world in the limited remaining time before it arrives (which is forlorn).

Incidentally, I do find it puzzling to try to imagine how we would manage to create an AI or AGI that is vastly superhuman at science and technology but not superhuman at law, policy, governance, diplomacy, human psychology, social interactions, philosophy, and so on, but my objection to space governance doesn’t require any assumption about whether this is possible or likely. It still works just as well either way.

As an aside, there seems to be no near-term prospect of solar panels in outer space capturing energy at a scale or cost-effectiveness that rivals solar or other energy sources on the ground — barring AGI or some other radical discontinuity in science and technology. The cost of a single satellite is something like 10x to 100x to 1,000x more than the cost of a whole solar farm on the ground. Project Suncatcher is explicitly a "research moonshot". The Suncatcher pre-print optimistically foresees a world of ~$200 per kilogram of matter sent to orbit (down from around a 15x to 20x higher cost on SpaceX's Falcon 9 currently). ~$200 per kilogram is still immensely costly. In my quick math, that’s ~$4,000 per typical ground-based solar panel, which is ~10-30x the retail price of a rooftop solar panel. This is to say nothing of the difficulties of doing maintenance on equipment in space.[1]

The barriers to deploying more solar power on the ground are not a lack of space — we have plenty of places to put them — but cost and the logistical/bureaucratic difficulties with building things. Putting solar in space increases costs by orders of magnitude and comes with logistical and bureaucratic difficulties that swamp anything on the ground (e.g. rockets are considered advanced weapon tech and American rocket companies can’t employ non-Americans).[2]

A recent blog post by a pseudonymous author who claims to be "a former NASA engineer/scientist with a PhD in space electronics" and a former Google employee with experience with the cloud and AI describes some of the problems with operating computer equipment in space. An article in MIT Technology Review from earlier this year quotes an expert citing some of the same concerns.

Elon Musk’s accomplishments with SpaceX and Tesla are considerable and shouldn’t be downplayed or understated. However, you also have to consider the credibility of his predictions about technology in light of his many, many, many failed predictions, projects, and ideas, particularly around AI and robotics. See, for example, his long history of predictions about Level 4/5 autonomy and robotaxis, or about robotic automation of Tesla’s factories. The generous way to interpret this is as a VC-like model where a 95%+ failure rate is acceptable because the small percentage of winning bets pay off so handsomely. This is more or less how I interpreted Elon Musk in roughly the 2014-2019 era. Incidentally, in 2012, Musk said that space-based solar was "the stupidest thing ever" and that "it's super obviously not going to work".

In recent years, Musk’s reliability has gotten significantly worse, as he’s become addicted to ketamine, been politically radicalized by misinformation on Twitter, his personal life has become more chaotic and dysfunctional (e.g. his fraught relationships with the many mothers of his many children, his estrangement from his oldest daughter), and as, in the wake of the meteoric rise in Tesla’s stock price and the end of its long period of financial precarity, he began to demand loyalty and agreement from those around him, rather than keeping advisors and confidants who can push back on his more destructive impulses or give him sober second thoughts. Musk is, tragically, no longer a source I consider credible or trustworthy, despite his very real and very important accomplishments. It’s terrible because if he had taken a different path, he could have contributed so much more to the world.

It’s hard to know for sure how to interpret Musk’s recent comments on space-based solar and computing, but it seems like it’s probably conditional on AGI being achieved first. Musk has made aggressive forecasts on AGI:

Musk’s recent comments about solar and AI in outer space are about the prospects in 2029-2030, so, combining that with his other predictions, this would seem to imply he’s talking about a post-AGI or post-superintelligence scenario. It’s not clear that he believes there’s any prospect of this in the absence of AGI. But even if he does believe that, we should not accept his belief as credible evidence for that prospect, in any case.