This is an essay I’ve drafted but haven’t completed — I’m posting it in the spirit of Draft Amnesty and because there’s a Debate Week on the topic; expect mistakes, cut-off sentences, missing context, etc., and feel free to ask follow-up questions here or in this thread! This is a draft as part of a bigger essay series I'm working on, on “Better Futures”. |

I define moral error as an outcome where most future beings endorse the civilisation that they inhabit, but where there is an enormous loss of value because those future beings’ preferences are for the wrong things.

In this post I list some examples of axes for moral error: decisions where mistakes by future decision-makers could result in the loss of most possible value. I do not try to be exhaustive; my goal is to illustrate the variety and number of different decisions that could lead to moral error.

This exercise increased my confidence in the idea that, if future decision-makers act on the wrong moral view, then that would very likely result in the loss of most value. This is true even if the view they have is reasonable (and it’s especially likely if decision-makers go all-in on optimising for one view).

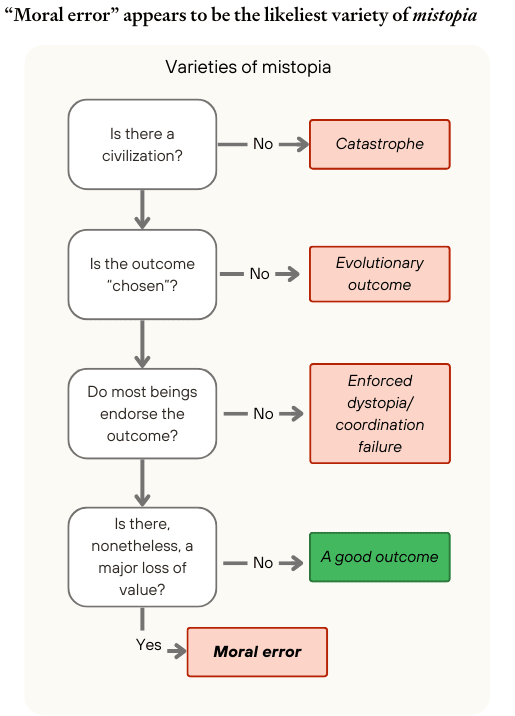

I define a mistopia as a society that is only a small fraction as good as it could have been. A society being mistopian doesn’t mean that the society is worse than nothing or that there’s more suffering than happiness in that society. A mistopian civilisation society could still be, on balance, better than a barren world — it could even be very good compared to today, just much less good than would be possible. “Moral error” appears to me to be the likeliest variety of mistopia.

Where should we look for potential sources of moral error?

One way to identify potential sources of moral error is to think of moral atrocities of the past, and imagine them returning to widespread acceptance. So, for example, the future could see the return of widely accepted slavery, racial hierarchy, torture of one’s enemies, or totalitarianism. But that gives us only a very limited set of possibilities; of all possible moral catastrophes, we have probably only witnessed a tiny handful in history. Restricting ourselves in this way might make moral error seem much less likely than it really is.

A different method — and the one I’m focusing on here — is to consider various positions in moral philosophy, explore the differences in their recommendations about what society should look like in the long term, and identify situations in which the wrong choice would result in the loss of almost all value. Existing positions in moral philosophy show us what views people come to with a bit more reflection than is usual (though vastly less reflection than might occur over the long run, or in a post-AGI world). The exercise shows just how different the evaluations of different plausible futures are, by what can otherwise seem like very similar moral views.

This process still doesn’t give us anywhere close to a complete picture of the types of moral error that could occur and feels a little artificial. But it can give us a helpful glimpse.

What philosophical assumptions does the idea of “moral error” rely on?

The idea of moral error can seem to have a very realist flavour. But we needn’t assume objectivist realism to be worried about moral error. To see this, consider a simple subjectivist view on which the claim “I think X is morally better than Y” is true iff I think I would prefer X to Y if I had sufficient time to reflect on my preferences in idealised conditions. On this view, the future suffers moral error if you would regard it as missing out on most possible value by the lights of your own reflective preferences.

My discussion might also have a particularly utilitarian flavour. But the concept of moral error does not bake in the truth of some variant of utilitarianism, either. Variants of utilitarianism are particularly useful to illustrate moral error, as they are simple theories that can quickly give a quantitative sense of how bad different moral mistakes are. But moral error should be taken very seriously on any plausible non-utilitarian view, too.

Outline of the list of axes for moral error

Preference-satisfactionism, hedonism, and other theories of wellbeing

Population ethics: duration and number of lives

Other issues related to population ethics

The trade-off between happiness and suffering

The moral status and rights of digital beings

Other issues related to capacity for wellbeing

Should we value diversity of life?

The trade-off between growth and conservation

Causal and non-causal decision theories

Meta-ethics: should society encourage change of one’s preferences?

More generally: change versus stasis

Listing some examples of axes for moral error

Preference-satisfactionism, hedonism, and other theories of wellbeing

Currently, hedonism, preference-satisfactionism and the objective list view give fairly similar recommendations about how to improve people’s lives. But that might be a contingent fact about our world: most of the time, we can help people by giving them instrumentally useful goods (such as money, education, or health); and, most of the time, people want objective goods which also improve the quality of their conscious experiences.

For a very technologically advanced civilization, capable of designing beings in very different ways, this convergence is unlikely to remain. The beings that achieve the most preference satisfaction per unit of resources would likely be very different from the beings that achieve the best experiences or most objective goods per unit of resources. For example, the future could be filled with “happiness machines” that have blissful positive experiences but have no autonomy or growth; this could be very good by hedonist’s lights, but of little value by an objective list theory’s lights.

Population ethics: duration and number of lives

Even if future beings have very high per-moment wellbeing[1], they could vary greatly in the length of their lives. They could mainly have very short lives if they are mainly digital, and are regularly reset to earlier times, and this counts as death; or if digital beings are regularly created for a particular task and then ended once the task is complete. Alternatively, future beings could mainly have very long lives, if they enjoy life and want to keep living, and have the ability and resources to keep extending their lives.

A world with many short-lived beings could lose out on most value from a number of perspectives.

For example, if a critical-level view of population ethics is correct, then lifetime wellbeing[2] needs to be above a critical level for a life to be valuable.[3] If the short-lived lives are short enough, then even though they have high per-moment wellbeing, those lives would be below the critical level and so make the world worse. If there are sufficient numbers of them, such a world could even be worse than nothing, on the critical-level view.

- Additionally, many views in population ethics value high average lifetime wellbeing, in addition to high total wellbeing. A world where most beings have very short lives would have much lower average lifetime wellbeing than it could have done with a smaller number of longer lives.

- And one could think that death is an intrinsic bad. On this view, a world with large numbers of short-lived beings would have a lot more death than it could have done, and that fact alone makes the world worse.

A future with only very long-lived beings is not a safe bet either, however; it seems quite possible that such worlds would lose out on almost all value. For instance:

- Lifetime wellbeing could be diminishing in years of life lived; perhaps a life that’s 10 times as long, at a given level of per-moment wellbeing is only twice as good. Or lifetime wellbeing could even be bounded above; I think this is the common-sense view, insofar as, for most people, there’s no life that’s so good that they would be willing to take a 99.9999999% risk of death in exchange for a 0.0000001% chance of that life.

- And a world full of long-lived beings could be much less efficient at producing total wellbeing than a world with large numbers of short-lived beings. For example, if the long-lived beings value diversity of experience, they will not want to only consume the most cost-effective goods, and will require ever-more exotic and expensive experiences in order to stay happy.

Population ethics poses other issues, too. Even assuming that all future beings have lives of exactly the same length, there is still the question of how many beings there are and what average wellbeing they have.

There might well be intense tradeoffs to be made between creating very many lives of low average lifetime wellbeing, or creating fewer lives of high average lifetime wellbeing. Depending on how total versus average wellbeing is valued, making a mistake in either direction could result in most value being lost.

The trade-off between happiness and suffering

There are various plausible views about how happiness and suffering trade off against each other. Perhaps those with power will have the choice between a future that involves an enormous amount of happiness but some amount of suffering, too, and a future that involves almost no suffering but much less happiness. Which of these two futures is better than the other would depend on how to trade off happiness and suffering. With a sufficiently extreme exchange rate, a future with an enormous amount of happiness but some amount of suffering could even be actively bad.

The moral status (and rights) of digital beings

Once AI becomes sufficiently advanced, there will be a hard challenge around how to incorporate digital beings into society. On one perspective, digital beings with moral status should be given all the same rights as human beings, including voting and other political rights, and to do otherwise would be to implement an unjust regime with second-class citizens, even if those digital beings have been designed to be willing servants.

On another perspective, giving digital beings voting rights would be a catastrophe. In the absence of population growth restrictions, we should expect the population of digital beings to quickly surpass the population of human beings. Giving digital beings voting rights would therefore mean handing over control of society to them. If what is of value comes from distinctively human preferences that are not shared by those digital beings, the result could be the loss of almost all value.

Even within worlds where digital beings do not have political rights, there could be a huge amount at stake depending on what welfare rights they have. If future decision-makers wrongly believe that digital beings have no moral status, then those digital beings might have much worse lives than they should. If, on the other hand, future decision-makers wrongly believe that digital beings do have moral status even though they don’t, then human beings might have worse lives than they should, in order to promote the welfare of digital beings.

We might also face decisions about whether to move towards worlds in which beings are mostly biological or digital; different moral views would evaluate these worlds in very different ways.[4]

More generally, moral views can differ in how they evaluate the capacity for wellbeing of different sorts of beings. For example, a human brain has over a million times as many neurons as an ant brain. Does a human being have a million times the capacity for wellbeing that an ant? It’s unclear, and one could reasonably think that the number is much higher or much lower than that.

In the future, this issue could have enormous importance. Perhaps the best future consists of beings with brains the size of humans, or the size of ants, or the size of galaxies, or somewhere in between. Again, getting this wrong could result in the loss of almost all value. Perhaps the capacity for wellbeing scales with the square of brain size: if so, then a single galaxy-brain would be vastly more valuable than a huge population of beings with human-sized brains. Or perhaps the capacity for wellbeing scales with the logarithm of brain size; if so, then the future with ant-brain-sized beings would be vastly more valuable than one with a much smaller number of beings with larger brains.

Of course, brain size might be quite unimportant in assessing a being’s capacity for wellbeing. But similar considerations would likely apply when assessing whatever it is that is relevant to capacity for wellbeing.

Should we value diversity of life?

Consider two possible futures for humanity:

- Variety: There is an enormous number, n, of lives with very high lifetime welfare w_H. These lives are varied and each is unique.

- Homogeneity: There is an enormous number, n, of lives with very high lifetime welfare w H+ε (which is arbitrarily close to w_H, but a tiny bit higher). These lives are qualitatively identical; their conscious experiences are subjectively indistinguishable, and their physical substrates are atom-for-atom copies of one another.

All impartial[5] theories of population ethics that have been proposed in the literature, as far as I know, evaluate B as better than A.[6] But intuitively, A is (much) better than B.

If the impartial theories are right, then choosing A would be a massive moral error. But if the intuitive view is right, choosing B would be a similarly grave mistake.

The trade-off between growth and conservation

Future society could end up using all available resources in productive ways, or it could choose to forbid the use of most of those resources. Some perspectives might regard the former outcome as a moral catastrophe: environmentalist views are the most obvious, but also views (such as strict negative utilitarianism) on which the proliferation of civilisation is, overall, a bad thing. Other perspectives, including views on which having a larger population of sufficiently well-off people makes the world better, might regard widespread conservation as a moral catastrophe.

Causal and non-causal decision theories

Causal and non-causal decision theory might make quite different recommendations for how society should be structured. Causal decision theory would recommend making best use of the resources that people can affect — namely, those in our future light cone. Non-causal decision theory might recommend engaging in acausal trade: acting in a certain way in order to make it more likely that other beings, outside of our light cone or even our branch of the multiverse, act in a way that we prefer. From either perspective, someone following the other decision theory would be making a terrible mistake.

Meta-ethics: should society encourage change of one’s preferences?

A society that in the future believes there is no objective moral truth might not be nearly as willing as one that does believe in an objective moral truth to: (i) reflect upon and alter their own preferences in the light of argument; (ii) have consistent moral views; (iii) take weird moral ideas seriously. At worst, such a society could just act on their own unreflective preferences rather than try to improve upon them at all. In any of these scenarios, if that society is mistaken and there is an objective moral truth, then society’s moral views could be systematically wrong, and most possible value could be lost.

Alternatively, perhaps at some point those in power believe there is a convergently-discoverable moral truth, when there isn’t. They therefore might not be sufficiently concerned about other groups (including AIs) taking power from them, because they believe that those groups would converge on the right moral views. Again, most possible value could be lost as a result.

Change versus stasis

More generally, it’s not obvious what counts as moral progress, and what counts as value drift. We could get it wrong in either direction. Perhaps we let moral norms continue to change in the future, when we should have locked-in something close to contemporary views. Or perhaps the first generation with the power to do so locks in their unreflective values, even though those are far away from those values that would seem best upon deep reflection.

Empirical errors

Though I’ve mainly highlighted errors that could be made about normative theory or axiology, it’s possible that there could be moral error as a result of mistakes concerning matters of fact, too. For instance, if we mistakenly thought it was not physically possible to settle other star systems then we might miss out on the possibility of creating a larger good civilisation.

There are convergent instrumental reasons for coming to accurate views about matters of fact for most issues. But these reasons might still not be strong enough to cause us to actually form the correct views – in present society there are many untaken opportunities here. And sometimes the instrumental reasons might favour false beliefs. For example, it’s plausible that, historically, false religious beliefs have been useful for increasing the amount of trust and cooperation within large societies. Perhaps the same selection pressures favours similar false beliefs in the future, too.

Concluding notes

This has been a litany of ways in which we could lose out on most possible value because future decision-makers want the wrong things, but it’s barely scratched the surface.

I’ve focused on views that are relatively obvious, in the sense that they have been suggested by at least some philosophers. But what’s morally correct might be much weirder than anything I’ve canvassed here. Perhaps what’s best is a society that we today would find deeply repugnant; or perhaps it’s something too bizarre and alien for us to even comprehend.

What’s more, I’ve assessed possible futures just in terms of the outcomes they involve. But perhaps what matters is also the process we take — for example, whether it's sufficiently inclusive, or democratic, or did not involve significant wrongs along the way. So, even if we get a very good outcome, we could still lose out on almost all value if the wrong process got us there.

In the end, I see numerous sources for and ways we could end up in moral error. And I don’t expect us to solve this problem by default.

One of the major reasons I’m worried about these sources of moral error is that they’re unlike the kinds of issues we’ve addressed before. Much of the moral progress we’ve made over the past few centuries has come from expanding the moral circle. And much of the mechanism for that change is that the disenfranchised (like women, the enslaved, people of colour, and LGBTQ+) have been able to advocate for themselves. Whereas, so far, on issues where the disenfranchised cannot advocate for themselves (such as nonhuman animals or future generations), moral progress has been faltering, even when the arguments in favour of extending the moral franchise to these groups are incredibly strong.

Most of the issues we’ve canvassed in this post are cases where the disenfranchised cannot advocate for themselves, or where it doesn’t even make sense to talk about “the disenfranchised”. In fact, on many issues advocacy could go in the wrong way. Suppose that in the future there was a large underclass of digital workers with no rights and miserable lives. Would they unite and advocate for better living conditions? No. After the point at which beings are designed rather than seeded, they can be designed to endorse the lives they have, whatever those lives are. A society with the motive to create an underclass of digital workers would be strongly incentivised to ensure that those workers were designed to approve of that regime, even if they ended up being miserable. Far from advocating for their rights, that underclass of digital beings would be advocating against their own liberation.

- ^

Definition. Per-moment wellbeing: how good or bad someone’s life is, for that person, at a particular moment in time.

- ^

Definition. Lifetime wellbeing: how good or bad someone’s life is overall, for that person.

- ^

Definition. Value of a life: the amount by which a life intrinsically contributes or takes away from the impartial good.

- ^

Digital beings could potentially be much cheaper to create, could live in a much wider range of environments, and could lead much happier lives with a given unit of resources than biological beings. Digital beings could probably possess many of the properties that we think give human beings moral status to a much greater degree. On many moral views, therefore, it would be imperative to have a future consisting mainly of digital beings rather than human beings.

On the other hand, on many moral views there is something special and distinctive about humanity per se. A future where almost all beings are digital, or even where there are no human beings remaining, could seem quite dystopian from this perspective.

Similar considerations would apply to human beings versus “posthuman” successors, even if those successors were still biological.

- ^

I say “impartial” because some narrow person-affecting views could regard the two populations as incomparable.

- ^

That all extant impartial population axiologies evaluate B as better than A can be seen by noting that A and B both contain the same number of lives, both are perfectly equal, both only contain lives with welfare that is high enough to surpass any “sufficiency” threshold, but B has higher total (and therefore average) wellbeing. But the evaluation that B is better than A also follows from two more basic principles:

Anonymity: The value of a population depends only on how many lives instantiate each lifetime welfare level. (Wording taken from Teru. As he notes, “The assumption of anonymity means that we can make evaluative comparisons between distributions, in such a way that one population is at least as good as another just in case its distribution is at least as good,” where he defines a distribution as “a finite, unordered list of [lifetime] welfare levels, perhaps containing repetitions.”)

Strong Pareto: If two populations A and B contain exactly the same people, and A is at least as good for every person, and strictly better for at least one person, then A is better than B.

As far as I know, all impartial population axiologies that have been proposed in the literature endorse these principles. But any view that endorses both these principles regards Homogeneity as better than Variety.

Nice post! I agree moral errors aren't only a worry for moral realists. But they do seem especially concerning for realists, as the moral truth may be very hard to discover, even for superintelligences. For antirealists, the first 100 years of a long reflection may get you most of the way to where your views will converge towards after a billion years of reflecting on your values. But the first 100 years of a long reflection are less guaranteed to get you close to the realist moral truth. So a 100-years-reflection is e.g. 90% likely to avoid massive moral errors for antirealists, but maybe only 40% likely to do so for realists.

--

Often when there are long lists like this I find it useful for my conceptual understanding to try to create some scructure to fit each item into, here is my attempt.

A moral error is making a moral decision that is quite suboptimal. This can happen if:

--

Some minor points:

I think this is overall an important area and am happy to see it getting more research.

This might be something of a semantic question, but I'm curious if you what you think of the line/distinction between "moral errors" and say, "epistemic errors".

It seems to me like a lot of the "moral errors" you bring up involve a lot of epistemic mistakes.

There are interesting empirical questions about what causes what here. Wrong epistemic beliefs clearly lead to worse morality, and also, worse morality can get one to believe in convenient and false things.

As I think about it, I realize that we probably agree about this main bucket of lock-in scenario. But I think the name of "moral errors" makes some specific assumptions that I think are highly suspect. Even if it seems like the case now that differences of morality are the overriding factor to differences in epistemics, I would place little confidence in this - it's a tough topic.

Personally I'm a bit paranoid that people in our community have academic foundations in morality more than epistemics, and thus correspondingly emphasize morality more because of that. Or, it seems a bit convenient when specialists in morality come out arguing about "moral lock-in" as a major risk.

Unfortunately, by choosing one name to discuss this (i.e. "Moral Errors"), we might be locking in some key assumptions. Which would be ironic, given that the primary worry itself is about lock-in of these errors.

(I've written a bit more on "Epistemic Lock-In" here)

Executive summary: Moral error—where future beings endorse a suboptimal civilization—poses a significant existential risk by potentially causing the loss of most possible value, even if society appears functional and accepted by its inhabitants.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.