Introduction

In this post, I present what I believe to be an important yet underexplored argument that fundamentally challenges the promise of cultivated meat. In essence, there are compelling reasons to conclude that cultivated meat will not replace conventional meat, but will instead primarily compete with other alternative proteins that offer superior environmental and ethical benefits. Moreover, research into and promotion of cultivated meat may potentially result in a net negative impact. Beyond critique, I try to offer constructive recommendations for the EA movement. While I've kept this post concise, I'm more than willing to elaborate on any specific point upon request. Finally, I contacted a few GFI team members to ensure I wasn't making any major errors in this post, and I've tried to incorporate some of their nuances in response to their feedback.

From industry to academia: my cultivated meat journey

I'm currently in my fourth year (and hopefully final one!) of my PhD. My thesis examines the environmental and economic challenges associated with alternative proteins. I have three working papers on cultivated meat at various stages of development, though none have been published yet. Prior to beginning my doctoral studies, I spent two years at Gourmey, a cultivated meat startup. I frequently appear in French media discussing cultivated meat, often "defending" it in a media environment that tends to be hostile and where misinformation is widespread. For a considerable time, I was highly optimistic about cultivated meat, which was a significant factor in my decision to pursue doctoral research on this subject. However, in the last two years, my perspective regarding cultivated meat has evolved and become considerably more ambivalent.

Motivations and epistemic status

Although the hype has somewhat subsided and organizations like Open Philanthropy have expressed skepticism about cultivated meat, many people in the movement continue to place considerable hope in it, or at minimum, maintain strong sympathy toward the concept. Yet there are numerous reasons to be skeptical, and it's worth debating whether promoting cultivated meat should remain among the priorities of EA or EA-supported organizations, and more generally to what extent the sympathy many EAs hold toward cultivated meat remains justified in 2025.

While I consider myself well-informed on cultivated meat, there are certainly more knowledgeable individuals who likely don't share my position, such as the people doing excellent work at GFI. Therefore, I don't wish to suggest that my skepticism automatically stems from superior knowledge of the subject. Moreover, many aspects remain uncertain, and we should place only limited confidence in many current studies.

Important limitations of this post include:

- The difficulty in predicting consumers' actual attitudes toward cultivated meat. Even the most rigorously conducted studies provide only limited insight, given today's general lack of familiarity with cultivated meat and uncertainty about how it will eventually be marketed. Similarly, studies on environmental impact or production costs remain speculative without data from large-scale production facilities.

- This critique relies on hypotheses that don't all have strong empirical foundations, though they appear reasonable enough to warrant consideration.

- My main argument seems relatively simple and straightforward, and I'm surprised it isn't discussed more frequently. I may have overlooked something significant.

Baseline assumptions for this discussion

Cultivated meat is likely environmentally better than conventional meat, but probably not as good as plant-based meat

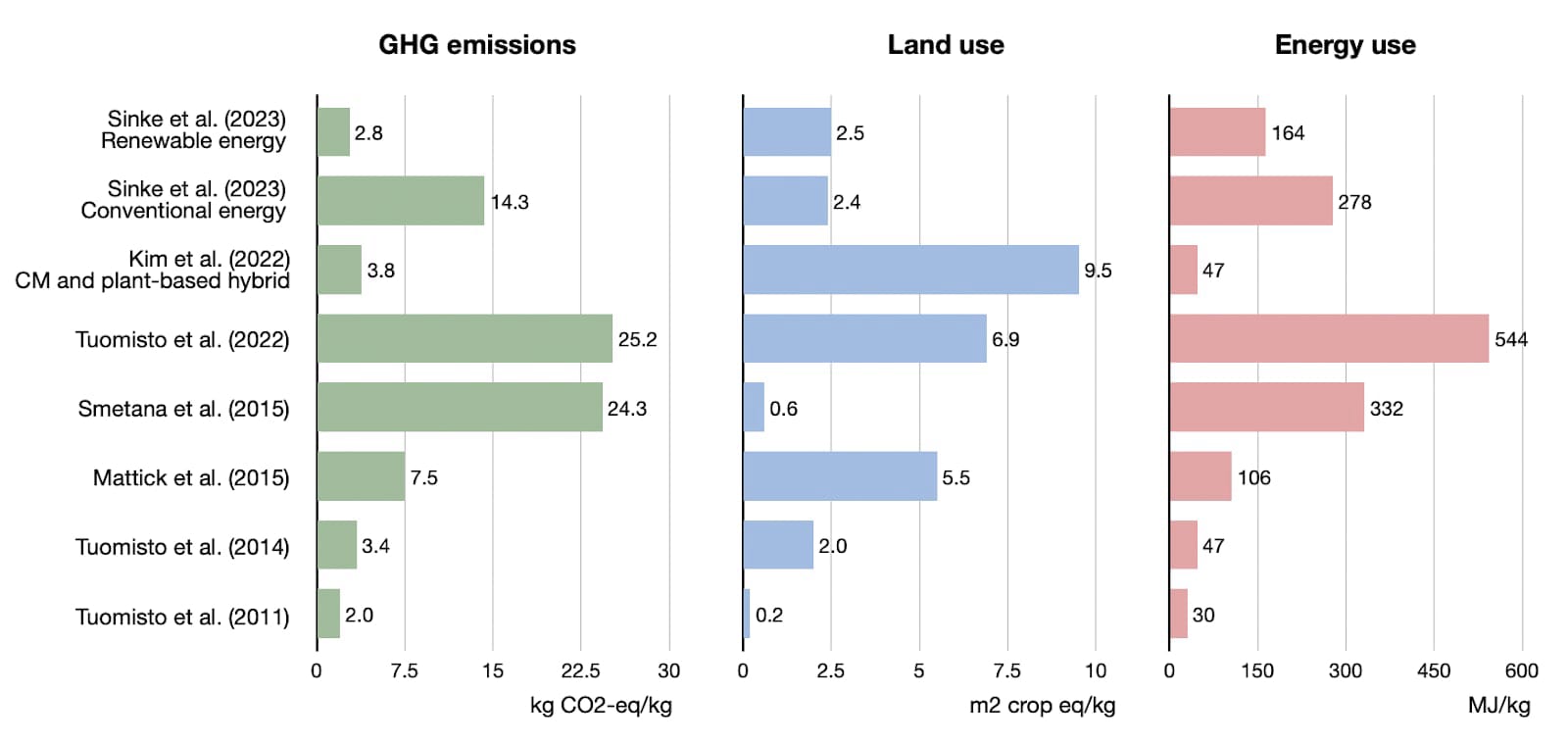

I don't contest that cultivated meat would likely be better for the environment than the average piece of conventional meat, particularly beef. Cultivated meat shows promising environmental advantages compared to conventional meat, particularly regarding land use. According to Sinke et al. (2023), cultivated meat would require 64% less land than chicken and up to 90% less than beef. Note however that other studies nuance the idea that cultivated meat would require much less land.

Comparison of the results of selected life cycle analyses about cultivated meat published in peer-reviewed journals.

Regarding greenhouse gas emissions, the results vary dramatically by energy source, cultivated meat produced with renewable energy demonstrates substantially lower emissions than beef, while with conventional energy sources, it actually performs worse than chicken, emitting more greenhouse gases. This stems from the fact that the production process remains extremely energy-intensive, approximately 5.5 times more than conventional meat.

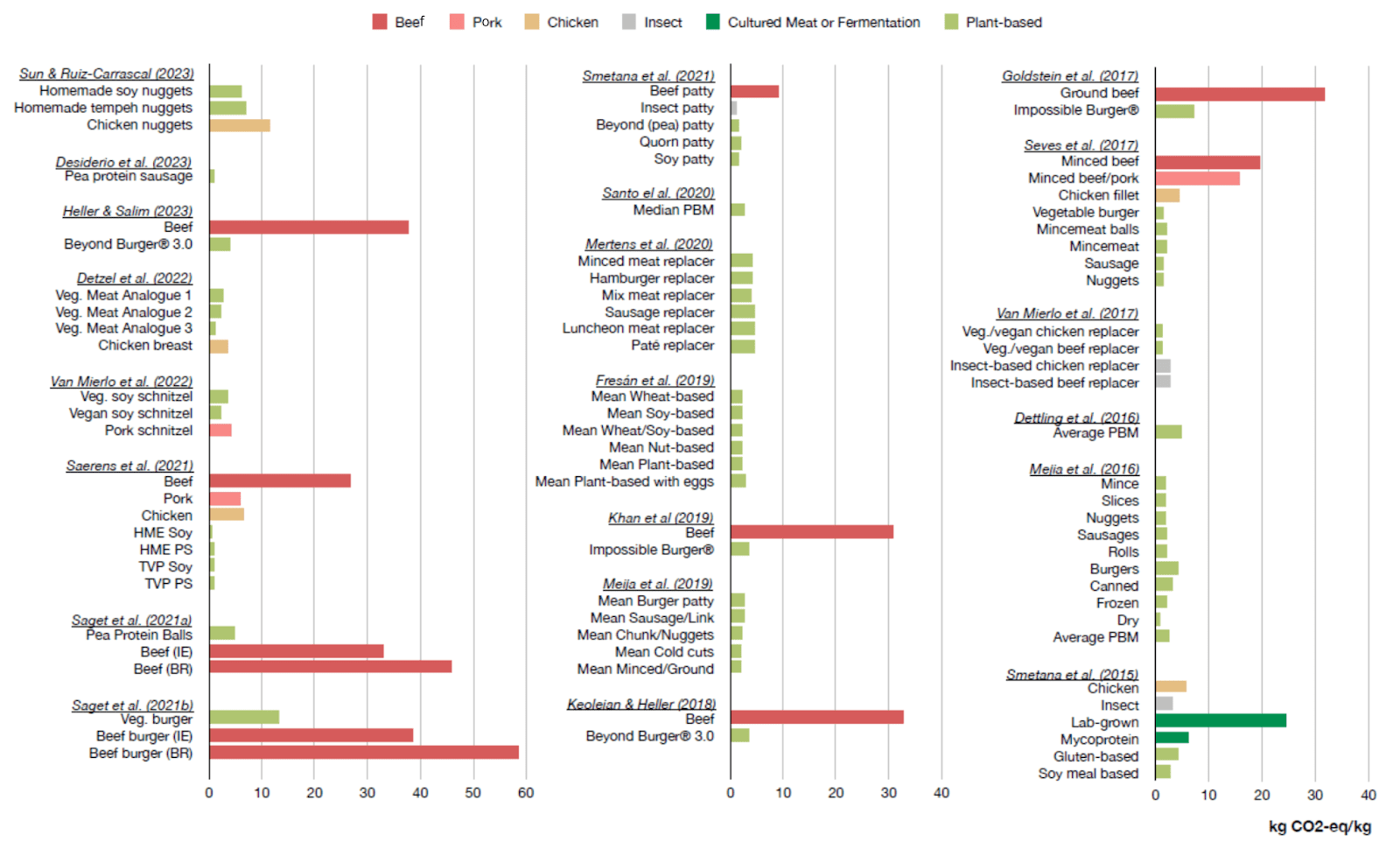

Plant-based meat demonstrably remains more promising from an environmental perspective. Below is a synthesis of the LCAs I've found regarding greenhouse gas emissions from different plant-based meats, noting that this is quite a broad category with, for example, processing methods that can vary considerably, which influences the final result.

Summary of GHG emissions from a selection of LCAs of plant-based meat substitutes

a) Values reported for PBMs in (Fresán 2019b; Mejia et al. 2019; Dettling et al. 2016) are means.

Cultivated meat will remain quite expensive for several years, and hybrid plant-cell products will likely appear on the market first

While cultivated meat made its market debut in December 2020, only four companies (excepting pet food) have obtained market authorization so far, and their products remain available in extremely limited quantities. To date, six publicly available TEAs (Techno-Economic Analyses) have scrutinized the production process of cultivated meat (I've chosen to ignore one concerning insect cells), with cost estimates and technical assumptions regarding bioreactor designs, media formulations, cell characteristics, aseptic requirements,cetc. varying dramatically, making direct comparisons challenging. You can look at this paper for a detailed comparison and summary of the different TEAs. Nevertheless, here are the estimates obtained by these TEAs:

Estimated costs for the production of 1kg of cultivated meat (wet matter)

| Study | 1kg production cost estimation |

| Risner et al. 2020 | $2 - $437 000 |

| Vergeer et al. 2021 | $6.43 (optimistic future scenario) - $22 421 (current cost for pessimistic scenario) |

| Humbird 2021 | $22 (fed-batch + amino acids obtained from hydrolysates) - $51$ (perfusion) |

| Garrison et al. 2022 | $63 (lowest) |

| Negulescu et al. 2022 | $17 (262,000 L airlift bioreactor) - $35 (stirred tank bioreactor) |

| Pasitka et al. 2024 | $23.26 - $26.44 |

Even with optimistic assumptions, it appears difficult to go below $20 at the moment and for the years to come. Note that I've also received information supporting these figures and order of magnitude from industry insiders. And these are just production costs, which don't include, for example, distribution and margins for various intermediaries.

As a result, a growing number of industry players are now adopting a different approach: hybrid products where cultivated cells represent just one ingredient among others, with the raw material being primarily plant-based. A typical example is adding animal fat cells, which are reputed to be very flavorful and difficult to imitate with plant-based alternatives. To my knowledge, there are no recommendations or standards regarding the desirable proportion of cells. Some companies claim to be aiming for 50/50. At the other extreme, recently the company Good Meat launched a product in Singapore containing only 3% cultivated cells.

While I believe that cost remains a crucial crux in the discussion and a legitimate concern regarding cultivated meat's potential, I choose not to delve deeper into this topic in this post, as it is already well-known to most people interested in the subject.

Cultivated meat is ethically better than conventional meat

The suffering inflicted by factory farming is immense, and reducing our reliance on systems that cause such harm is morally urgent. Cultivated meat would dramatically reduce the number of animals used in meat production, with donor animals potentially serving as what Van Dooren and others have called "sacrificial surrogates"—beings whose lives are subordinated to benefit others. Of course, just as some people decide to walk away from Omelas, I understand that some people reject this idea, particularly those with non-utilitarian moral frameworks. On the contrary, adherents to utilitarian frameworks might argue that farmed animals used for cultivated meat could have net-positive lives worth living, especially since there would be far fewer economic constraints on their welfare compared to conventional farming, and providing these animals with high living standards could even serve as positive PR for cultivated meat companies.

Additionally, I think that concerns about fetal bovine serum that often arise are not a genuine problem, given that eliminating it will be necessary to achieve economic viability and large-scale production. Several studies suggest this is possible, and of the few products that have obtained marketing authorization in recent years, some were not produced using media containing fetal bovine serum. The same applies to scaffolds and microcarriers, for which edible, non-animal alternatives are being developed and appear promising.

The main argument: cannibalization rather than conversion

A common misconception pervades discussions of cultivated meat (and other alternative proteins): the assumption that any product environmentally and ethically superior to conventional meat must necessarily yield net positive outcomes. This reasoning fundamentally misframes the issue. The critical question is not whether cultivated meat improves upon conventional meat, but rather whether it improves upon the specific alternatives it will actually displace in the marketplace.

The theoretical foundation supporting cultivated meat rests on its potential to deliver products with sensory characteristics remarkably similar to conventional meat, while dramatically reducing animal suffering and environmental degradation. The implicit promise is that such products would directly substitute for conventional meat consumption. However, this theory contains a crucial, often understated assumption: that cultivated meat would appeal to consumer segments distinct from those already receptive to other meat alternatives, thereby expanding the total market share diverted from conventional meat. Proponents envision capturing meat enthusiasts who remain deeply attached to meat's material qualities and sensory experience, consumers who have historically rejected plant-based alternatives as inadequate substitutes. But this should not be taken for granted.

Thus, if consumers viewed plant-based meat and cultivated meat as perfect substitutes, cultivated meat would have a net negative effect since plant-based alternatives perform better both environmentally and in terms of animal welfare (albeit marginally for the latter). In my view, several lines of evidence suggest this substitution scenario is quite plausible.

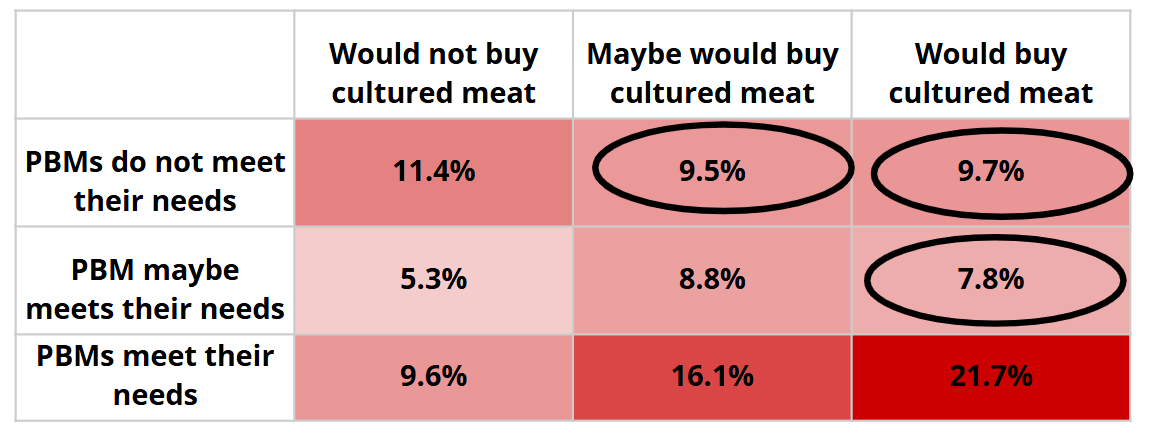

In one of the only, if not the only, study that looks at these substitution effects, Slade (2018) found a strong (although not perfect) correlation between preferences for plant-based alternatives and cultivated meat, indicating substantial overlap in consumer segments interested in both products. Bryant & Sanctorum (2021) found a similar correlation, although their results also suggest there is a segment of potential consumers who might prefer cultivated meat to plant-based meat.

This idea is reinforced by demographic studies showing similar characteristics among consumers interested in both alternatives: they tend to be younger, more educated, urban-dwelling, and environmentally conscious compared to conventional meat consumers. Acceptability studies consistently reveal that the psychological and demographic factors predicting willingness to try cultivated meat, including food neophilia, environmental concerns, and reduced attachment to conventional meat, are remarkably similar to those predicting plant-based meat adoption (Onwezen et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2024; Onwezen & Dagevos 2024). Some differences do emerge, cultivated meat appears to attract more men and self-identified regular meat eaters, but these findings primarily come from studies on willingness to try, which may not reliably predict actual purchasing behavior in real-world settings.

Now, remember also what we said about the cost of cultivated meat: it will likely first appear on our shelves in the form of hybrid products that are primarily plant-based. In this context, we have even more reason to believe there would be a strong substitution effect between plant-based meat and cultivated meat, typically because we would lose consumers with a "carnivore" profile. Unfortunately, we have very few studies on hybrid products and none that look at substitution effects between plant-based meat, cultivated meat, hybrid products, and conventional meat (but this is the subject of one of my working papers). It's concerning that these hybrid products remain understudied despite likely being the first commercially viable offerings. This represents a significant gap in the research literature, which predominantly focuses on products made only of cultivated cells.

I acknowledge that my argument relies on limited data. However this limited data actually underscores my argument: cultivated meat advocates need to demonstrate it will attract different consumers than plant-based alternatives, as this assumption forms the foundation of their strategic justification yet remains largely unexamined.

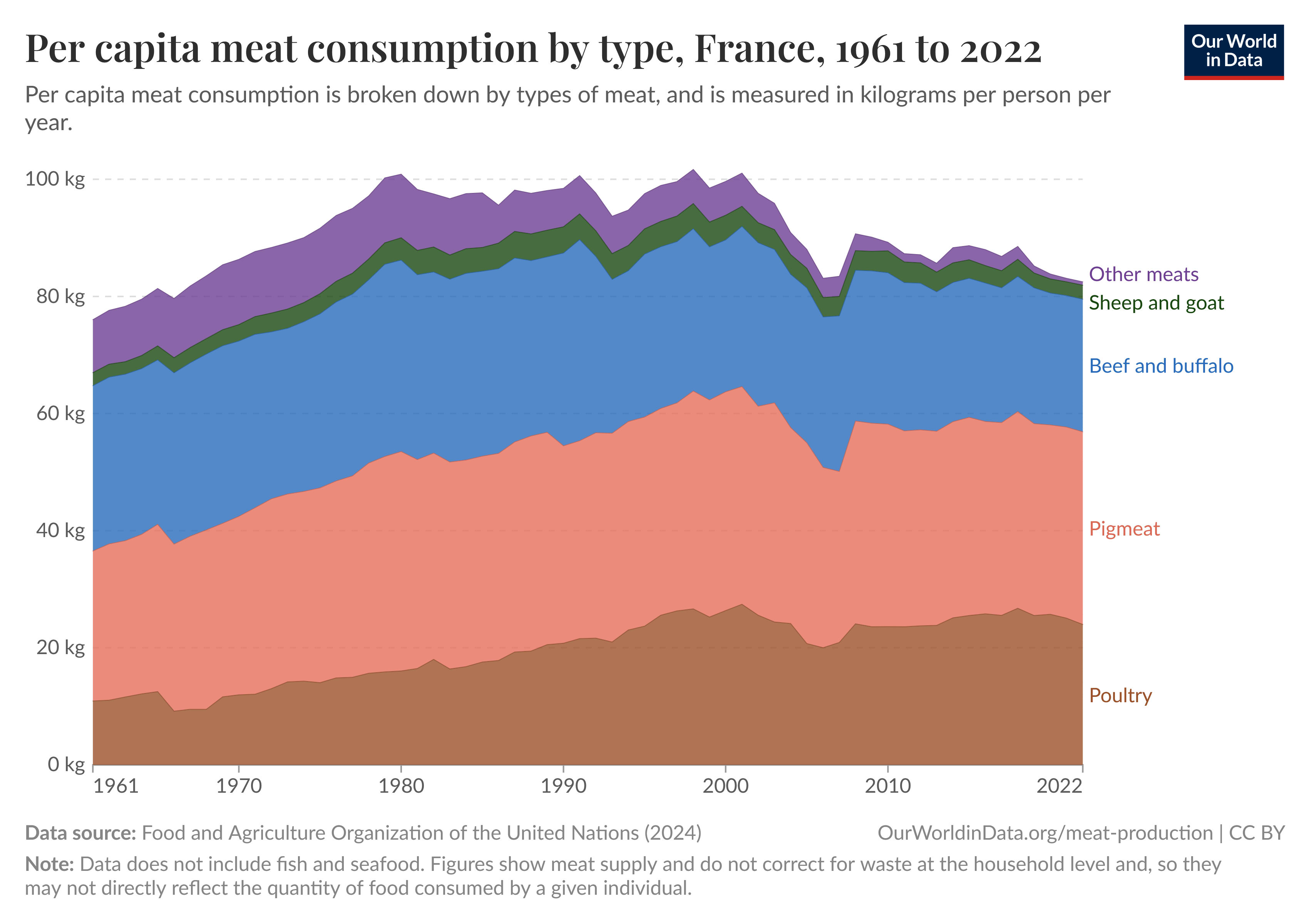

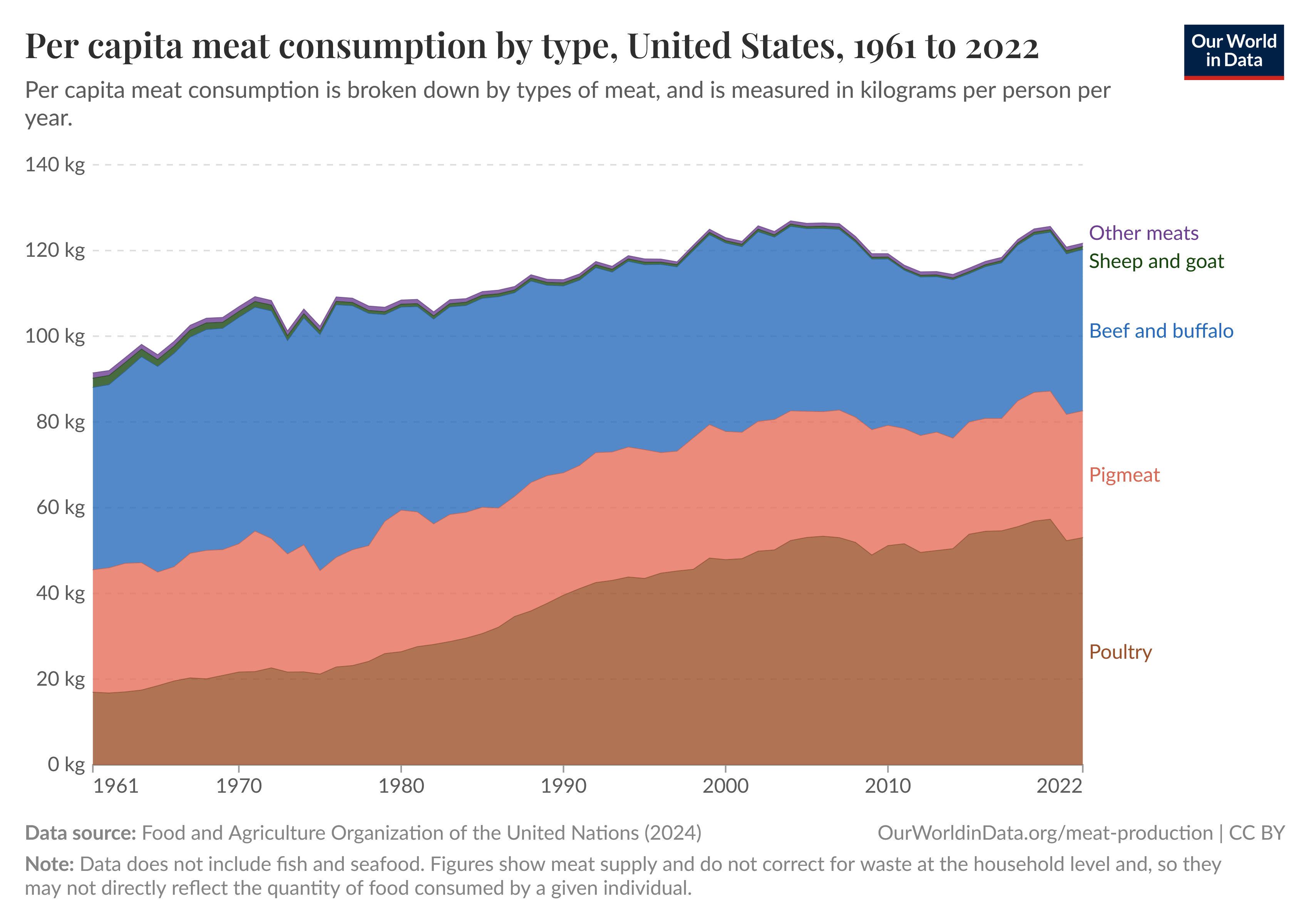

This echoes a broader concern about replacement assumptions. We often take for granted that alternative proteins will indeed replace meat. But this is not self-evident, as they could just be added to the current consumption basket rather than displacing meat, as some studies suggest. To draw a historical parallel, when industrial chicken farming developed in the second half of the 20th century, people didn't eat less of other meats; they just ate chicken in addition. As Jacob Peacock argued, even if alternative proteins become price-competitive, taste-competitive, and convenience-competitive, this alone would not guarantee they will replace conventional meat rather than simply exist alongside it. Likewise, a YouGov survey in the US found that only 13% expected to prefer eating “lab-grown meat” in a scenario where it was “indistinguishable from animal meat in terms of taste, nutrition, and cost.

Another important consideration is the uncertain timeline for cultivated meat's availability in meaningful quantities, whether as hybrid or 100% cellular products. Meanwhile, the organoleptic qualities of plant-based alternatives are improving at a remarkable pace, even though I acknowledge more progress is still needed. I recall when I became vegan about 10 years ago, I was eating tomato-flavored soy steaks that were absolutely disgusting. Today, we have a plethora of relatively convincing alternatives. By the time 100% cellular cultivated meat reaches market readiness the sensory gap might be negligible. Already, products like Beyond or Impossible burgers are nearly indistinguishable from conventional meat in fast-food settings. Recent innovative products such as La Vie’s ham, Swap’s chicken, and Juicy Marbles’ beef cuts demonstrate the accelerating quality of plant-based alternatives. Given these trajectories, it's reasonable to question what competitive advantage cultivated meat might offer when it finally achieves commercial scale, as plant-based products will have continued improving for years. Especially when considering that few consumers believe cultivated meat will match the taste of conventional meat, which calls into question the supposed inherent superiority sometimes granted to cultivated meat over plant-based alternatives.

Strategic drawbacks of the current focus

Beyond the potential waste of resources that the current focus on cultivated meat constitutes, it's not impossible that it directly has a negative impact on other meat alternatives. I see several mechanisms that could lead to this:

- Resource competition: while not every investment in cultivated meat directly diverts funding from other alternatives, finite capital and research attention create inevitable trade-offs in the alternative protein space. In a similar fashion, political capital spent securing regulatory frameworks for cultivated meat could instead support various policies that would create a more level playing field for all alternative proteins. Note that there are also strong arguments suggesting resources put into cultivated meat are not fungible; i.e., they would not otherwise go to plant-based meat. While it's true that food scientists working on protein texturization or flavor chemistry might easily transition between different alternative protein technologies, this is not the case for many specialists. For example, a tissue engineer specializing in cell culture media development would be unlikely to switch over to plant-based meat research if cultivated meat were out of the race.

- Media attention imbalance: cultivated meat captures disproportionate media coverage due to its technological novelty, while impressive plant-based innovations struggle to generate similar interest.

- "Humane-washing" risk: I've heard from several industry contacts that some companies were considering hybrid products not based on plants, but on conventional meat. In this scenario, there's a risk that cultivated meat serves as greenwashing or "humane-washing," especially if its share remains very small in the finished product.

- Psychological anchoring effect: cultivated meat's position as an idealized "perfect" solution may unintentionally devalue plant-based alternatives by framing them as inherently inferior interim options.

- Technological solutionism: the promise of future cultivated products enables moral licensing, with people postponing dietary changes—I've frequently heard statements like: "I'll wait for cultivated meat rather than go vegetarian today," which serves as a responsibility-deferring strategy. That said, it's worth considering that many people using cultivated meat as an excuse to defer making a dietary switch might not have changed their diet anyway, even in the absence of the promise of cultivated meat.

- Potential reputational spillover: cultivated meat faces significant political challenges and has been preemptively banned in several jurisdictions. This controversial status might possibly influence public perception of other alternative proteins. In the French context for instance, cultivated meat has faced preventive bans in public food services and schools. It is widely perceived negatively as it's associated with a form of interference by American billionaires in French agriculture, making any association with it a significant political and reputational risk.

The evidence that would make me eat my words (and maybe cultivated meat)

A compelling body of research could shift my position on cultivated meat's strategic value. I would reconsider if multiple well-designed studies analyzing substitution effects demonstrated that cultivated and plant-based meats appeal to sufficiently different consumer segments. Some overlap between these segments would be expected and acceptable, but it should be modest enough that cultivated meat would primarily expand the total alternative protein market rather than cannibalize plant-based sales. For this to be convincing, the research would need to examine not just hypothetical 100% cellular products, but also the hybrid products likely to dominate the cultivated meat market initially. Ideally, these studies would identify specific cellular content thresholds that influence consumer preference patterns, revealing whether acceptance meaningfully differs between products containing 3% versus 50% cultivated cells. Most importantly, this research would need to confirm that cultivated meat attracts consumers with specific aversions to plant-based options, people who would not adopt plant-based alternatives regardless of their continued improvement.

I should note that significant questions about scaling and cost reduction would still remain even with favorable consumer data. However, these challenges are already widely discussed, which is why I haven't focused on them in this post.

I should also acknowledge an important counterpoint suggested by some GFI team members with whom I've exchanged: taking a precautionary approach to cultivated meat could be risky because we have no guaranteed backup plan if plant-based alternatives, fermentation, and cultivated meat all fall short. Hybrid products that combine these technologies could potentially reach taste and price parity sooner than either technology alone (plant-based meat has further to go on taste, while cultivated meat has further to go on price). If hybrid products achieve taste parity even just a few years earlier than plant-based alternatives alone, the amount of suffering averted annually would already be immense. This perspective values pursuing multiple protein technologies simultaneously, given the urgency of addressing factory farming.

What I'd like to see change in the Effective Altruism approach to cultivated meat

I propose several changes to how the EA community approaches cultivated meat:

First, we should make the discussion of substitution effects more central when evaluating cultivated meat. We need to directly confront the risk that cultivated meat might primarily or even exclusively displace plant-based alternatives rather than conventional meat. We must understand that this isn't just a minor concern but a potential fatal flaw in the strategic case for cultivated meat.

Second, the EA community should temper its enthusiasm for cultivated meat until we have compelling evidence of low substitution effects between cultivated and other alternative proteins. The current level of support appears disproportionate to the available evidence.

Third, if we have reasons to believe that cultivated meat could reach a different consumer profile, we should develop specific strategies to ensure cultivated products target these right consumer segments if they are to advance our shared goals.

Fourth, resource allocation within the EA movement should reflect expected impact. While I recognize that currently few effective altruists directly financially support cultivated meat as individuals, the community's intellectual resources, attention, and organizational funding should be directed toward the alternatives with the strongest evidence of positive impact.

Finally, this evidence warrants thoughtful discussions about reconsidering resources currently invested in the promotion and development of cultivated meat by EA-aligned organizations like the Good Food Institute and, to a lesser extent, ProVeg.

I would like to thank Antonin Broi, Guillaume Vorreux, Joseph Ancion, and Romain Barbe as well as members of GFI for their valuable feedback and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article.

PS: I would be delighted to discuss this topic with you at EAG London—especially if you disagree with my perspective!

I meant that prohibiting abortion violates the right to bodily autonomy of the mother: her body is required for the pregnancy, and the pregnancy was against her will. So the body of the mother is used as merely a means. Abortion and killing a foetus does not violate the right to bodily autonomy of the foetus, because the body of the foetus is not used as a means to achieve someone else's ends. If the body of the foetus did not exist, there was no pregnancy and then the objective of the mother, not to be pregnant, is automatically achieved. So the presence of the body of the foetus is not necessary. So the body of the foetus is not used as a means.

Those 36% of US population that are against abortion, do not count, because they have an inconsistent ethic that involves unwanted arbitrariness (discrimination). Their ethic is speciesist, whereby human foetuses have a higher moral status than non-human animals. They believe that foetuses should not be killed whereas non-human animals are allowed to be killed. Such speciesist discrimination is arbitrary, and cannot be wanted by non-human animals. Hence unwanted arbitrariness. If such unwanted arbitrariness would be permissible, then we would be permitted to arbitrarily exclude the opinions of those people that are against abortion and arbitrarily exclude those people from democracy.

How many people would be against killing and eating individuals if those individuals had positive lives? If speciesism is excluded, and hence ‘individuals’ can refer to humans as well, then I expect a vast majority would be against such killing. Even if that means the individuals are not brought into existence.

About your total utilitarianism: the loss of welfare of a human who loves the taste of meat but is no longer allowed to eat meat, is smaller than the loss of welfare of all the animals who would be prematurely killed and eaten by that human. Hence, breeding animals but not killing and eating them, would increase total welfare. Also: the loss of welfare of a human who gives a bit of money to an animal sanctuary is smaller than the loss of welfare of animals on a sanctuary that lacks money to buy things for the animals. Hence, to increase total welfare, the human should give a bit of money to the animal sanctuary. And by the same reasoning he should give some money to another sanctuary that breeds and helps extra animals. And so, according to total utilitarianism, the human is not allowed to eat meat and is obligated to donate a lot of money to animal sanctuaries.

You are correct to assume that people would not want to farm lots of animals with super high welfare if they were not being raised for meat. That means those people are not total utilitarians.

If you want to maximize the ratio of annual welfare and cost, and if annual welfare does not explicitly depend on the lifespan of the animals, then you run into the replacement problem: the belief that killing an animal painlessly and bringing another animal into existence that has the same momentaneous welfare, is morally neutral. That would assume that animals would not have a personal identity over time. But there is evidence that animals are concerned about their future and do not want to be prematurely killed.

To be honest, I think that you are deluding yourself by believing that expectational total hedonistic utilitarianism is not that demanding. The belief that huge sacrifices would cause you to be less effective in doing good, seems to be like merely a rationalization. I don’t know of any total utilitarian who could not do a little more sacrifice in order to do more good. You can donate to the point that you are very poor and still work as hard, or even harder, to earn as much money, or even more money. I think total utilitarians should at least be honest and acknowledge that they are not doing all the things that would maximize total welfare. All total utilitarians that I know, are able to donate a little bit more on the margin and do more good.

About future human-years: a human who exists today can validly complain today that his/her welfare in the future is discounted. A human who does not exist today and will never come into existence cannot validly complain today that his/her welfare in the worlds where s/he is brought into existence in the future, is discounted. Hence, future human-years of humans who exist today always count at least as much as future human-years of humans who will never exist. Note that most humans believe that they have a personal identity over time, that they do identify themselves with future human-years.