Disclaimer: all beliefs here are mine alone, and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of my employer or any organization I work with.

Summary: This is my best attempt to explain my beliefs about AI existential risk, leaving none of my assumptions unstated or unchallenged. I’m writing this not because I’m confident that I arrived at the right answer, nor because I think I’ve stumbled on an especially clever insight. I’m writing this because laying out my thought process in full detail can be a helpful tool for thinking clearly and having productive dialogues. If you disagree with any of the points I’ve made, then I encourage you to write your own P(doom) explanation in a similar style.

Introduction

I just came back from Manifest, where I had the privilege of participating in a live AI doom debate with Liron Shapira of the AI Doom Debates newsletter. Shapira self-describes as an AI doomer – meaning, he believes that there’s a roughly 50% chance that advanced AI systems will kill all of humanity within our lifetimes. While I agree that AI existential risks are plausible, I am not nearly as pessimistic as he is. This debate was a good opportunity to sort out our differences and identify cruxes in our arguments.

I don’t agree with everything that Shapira said, but I appreciate the effort he put in to make the debate more structured and legible. In particular, he analogized the debate to an AI “Doom Train”: he identified 11 claims that contradict the AI doom narrative, with the implication that if you don’t believe in AI doom, you must agree with at least one of the 11 claims. The claims are as follows:

- AGI isn’t coming soon

- Artificial intelligence can’t go far beyond human intelligence

- AI won’t be a physical threat

- Intelligence yields moral goodness

- We have a safe AI development process

- AI capabilities will rise at a manageable pace

- AI won’t try to conquer the universe

- Superalignment is a tractable problem

- Once we solve superalignment, we’ll enjoy peace

- Unaligned ASI will spare us

- AI doomerism is bad epistemology

I admit that while I have thought about each of these problems, I have not until now formulated a coherent answer to all of them. Like many people, I obtained my P(doom) mostly through vibes rather than any sort of rigorous reasoning. But since the Doom Debates team gave us such a useful scaffold to think about this subject, I figure that I’ll use it to both clarify my own thinking and make that thought process legible to you, my readers. I will cover each claim, and give my probability for believing that that claim is true.

The 11 Claims

1. AGI isn’t coming soon (15%)

Both “AGI” and “soon” are somewhat ill-defined in this statement. For the purposes of this article, I’ll use the term artificial general intelligence (AGI) as it’s most commonly used – to mean an AI system that can outperform human beings at all significant cognitive tasks. And, I’ll say that “soon” means “by 2040”. 2040 is a totally arbitrary date, but I think it works as well as any other arbitrary date I could choose.

Longtime readers of my blog will know that I’ve believed in short AGI timelines ever since Situational Awareness was published last summer. My timelines have grown slightly longer since then, but not by much. In fact, it seems like short AGI timelines have finally started coming into the popular consciousness, as evidenced by the recent popularity of AI 2027.

I am not very technically advanced, nor am I an insider in the U.S. government, the Chinese government, or any of the leading AI labs. So, I don’t have any special insights into the current state of AI progress that you can’t find on your own. There are plausible arguments for and against short- to medium-term AGI development (see 80,000 Hours’s articles on the case for and the case against AGI by 2030). In my opinion, the “for” case is more likely, but not overwhelmingly so.

2. Artificial intelligence can’t go far beyond human intelligence (1%)

This never seemed like a very plausible argument to me. Assuming that intelligence is a real and significant trait that a being can have, I see no reason to believe that humans have mastered that trait. Even the smartest humans have limits on how fast they can learn new things, how well they can remember the information they’ve learned, and how creative they can be in using that information to generate novel and useful discoveries. Why should I believe that John von Neumann is the upper limit? I see no reason, in theory, that we couldn’t have somebody twice as bright, twice as quick-witted, and twice as creative as von Neumann.

Saying “the smartest human has an IQ of 200; therefore, no being could possibly have an IQ above 200”[1] seems as implausible to me as saying “the fastest human can run 100 meters in 9.58 seconds; therefore, no creature could possibly run 100 meters in faster than 9.58 seconds”.

So, I think it’s basically inevitable that if/when we reach AGI, artificial superintelligence (ASI) will come soon thereafter.

(The smarter version of this claim is that while ASI might in theory be possible, the jump between AGI and ASI is non-trivial and could take longer than we expect it to. I believe that such a “long gap” scenario is plausible, but it doesn’t really affect my P(doom). It only affects how soon I believe doom would occur after the advent of AGI.)

3. AI won’t be a physical threat (1%)

This is the claim that because AI is “just” a piece of code, it will never pose a threat to humans in the real world.

Again, not a very plausible argument to me. The idea that you can “just unplug AI if it goes rogue” sounds clever for about 2 seconds, until you seriously think about it. If AI were just a single being running on a single computer somewhere, then we could plausibly contain it. But AI is not that. There will be many instances of a given AI, and these instances might be running in hundreds, thousands, or even millions of computers around the world. Unplugging one of those computers might be easy enough, but unplugging all of them in time to avert catastrophe would involve a large degree of human coordination to pull off. And that’s assuming that we can even recognize the danger in time, which is also not guaranteed. If even one of the malicious AI instances manages to not be shut down, then it could use its superhuman persuasive abilities to convince humans in the real world to give it resources or give it a robot body. And with those resources and robot body, it could take actions to amass even more resources and more robot bodies. And once that happens, the malicious AI will be a physical threat.

This is one of the oldest arguments in the AI safety world, and for 20 years none of the proponents of “just unplug it” theory have offered a compelling account of how we would reliably do that. I recommend this post from LessWrong if you want to learn more.

4. Intelligence yields moral goodness (30%)

This claim feels way out of my area of expertise. I’m no philosopher. I have no clue whether moral realism is true or not. I have no clue whether the Orthogonality Thesis is true or not. I’ve read some of the leading proponents of both worldviews, but none of their arguments were all that persuasive to me. I’m inclined to believe that the Orthogonality Thesis is probably true, but that belief comes more from vibes than from any rigorous argument I could give you.

5. We have a safe AI development process (20%)

The word “safe” is not well-defined in this statement, so it’s hard to know what exactly this is claiming. I’ll reword this claim as, “In the event that a misaligned AGI emerges, humans will be able to identify it and stop it from taking over the world.”

Certainly, there are reasons to be pessimistic here. Already, AI developers have rushed or skipped safety tests in their hurry to ship new products as fast as possible, and this need for speed only seems to be increasing as AI capabilities grow stronger. And if the competitive dynamic between AI companies wasn’t bad enough, there’s also the competitive dynamic between the U.S. and China. Both America and China want to win the AI race, and American and Chinese leaders might be willing to cut corners on AI safety in order to make that happen. Additionally, decision-making is generally more prone to error in times of high geopolitical tension or war, which makes the increasing tensions between America and China all the more dangerous. So, it seems likely that warning signs of a coming misaligned AGI will be missed or ignored until it’s too late.

That being said, the question on the table is not, “Are AI developers acting responsibly?” (The answer to that question would almost certainly be no.) Rather, the question is, “Will AI developers be successful at stopping a misaligned AGI, should it emerge?” And this could still plausibly be true, even if the developers are cutting corners. To give a somewhat crude analogy, the Union army made many mistakes during the American Civil War, yet despite those mistakes it was still good enough to beat the Confederacy.

These companies may be reckless, but they’re not stupid, nor do they have a death wish. As soon as they detect a serious threat from misaligned AI, they will immediately put their top engineers and cybersecurity experts to work to try and mitigate that threat. And while I certainly wouldn’t want to rely on that as humanity’s survival plan, I also don’t think it’s impossible that that plan could work.

6. AI capabilities will rise at a manageable pace (N/A)

(I view this as basically a repeat of the previous question, so everything I said there applies here.)

7. AI won’t try to conquer the universe (50%)

In order for an AI system to try to conquer the universe, three things each have to be true:

- The AI system has inherent motivations / goals.

- The AI system’s goals are misaligned to human goals.

- The AI system’s goals are expansionary – meaning, that it desires to take up as many resources as possible.

If any of these things are not true, then the AI will not try to conquer the universe. If A isn’t true, then the AI can’t “try” to do anything (at least not without some human directing it). If B isn’t true, then the AI won’t try to conquer the universe unless we want it to. And if C isn’t true, then even if the AI is misaligned, it won’t pose a threat to us. So, I’ll split claim 7 into 3 smaller claims:

7A: By default, AGI will not be truly agentic. (2%)

Many AI doomers take it for granted that AI has to be some kind of maximizer – in other words, that it has to have some goals that it strives to achieve, independent of what its creator might have intended for it to do. Indeed, the current RL-based framework for building AI basically guarantees that AIs will be maximizers. (They’re literally giving the AI a function to maximize, and selecting for those instances that succeed.) Assuming that current methods scale to AGI, I think it is overwhelmingly likely that that AGI will be a maximizer.

That being said, I don’t think the maximizer outcome is completely overdetermined. It’s conceivable to me that we can somehow produce a superintelligence that is non-agentic. (Or, to the extent it’s agentic, it’s only instrumentally agentic in the service of its creators’ goals. But it won’t intrinsically pursue goals of its own accord.) Not a likely scenario in my mind, but not totally impossible either.

7B: By default, AGI will be aligned to human interests. (40%)

This is another one of those classic LessWrong debates. Many smart people have been arguing for a long time over whether or not we should expect that by default, an agentic AI system will be aligned to its creators’ interests or to its own independent (and likely divergent) interests. I don’t have anything especially interesting or insightful to add to that conversation.

If you had asked me a year ago whether alignment by default is true, I would have said probably yes at a likelihood of ~60%. But in the year since, we have seen multiple pieces of evidence suggesting the AI misalignment is not just a speculative concern, but a real property that current models are capable of exhibiting. I’m referring in particular to Anthropic’s “Alignment faking in large language models” paper (December 2024) and OpenAI’s “Detecting misbehavior in frontier reasoning models” (March 2025). Neither of these pieces of evidence are overwhelming, but they’re enough to update me from “alignment-by-default is probably true” to “alignment-by-default is probably false”.

7C: By default, AGI will be misaligned but non-expansionary. (8%)

As the classic Yudkowsky quote goes, “The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of atoms which it can use for something else.” But how do we know that the AI even wants your atoms? It’s possible that even if the AI has interests misaligned from your own, it will still have no desire to take over the universe. Consider two analogies from human history:

Some of the most intelligent humans in many cultures choose to be monks. They choose to go into caves and consume as few resources as possible, content to spend all their time on intellectual and spiritual pursuits. Maybe an AGI would be content as a “brain in a jar” – spending some amount of energy on computations, but otherwise not bothering anybody.

In the early 15th Century, Ming Dynasty China sent a huge Treasure Fleet across the Indian Ocean, going as far as India, Arabia, and East Africa. As the largest, most well-organized, and most technologically advanced state in Asia at the time, it’s probable that had the Ming Emperors wanted to conquer and colonize large portions of South Asia and Africa, they could have done so. Yet, they didn’t. After just a few expeditions to the southwest, the Hongxi Emperor decided to halt the voyages, burn all the ships, and destroy any records that the voyages had ever occurred. It’s still not entirely clear to historians why this happened. But the leading theory is just that the Chinese didn’t care about exploration and conquest in the way that later generations of Europeans would. China was already the world’s center of trade and civilization (or so the Chinese believed), so they felt no need to expand outward. Similarly, we can imagine a “Hongxi AGI” which takes over some portion of the universe – maybe an island, or a planet, or a solar system – and then leaves the rest of the universe alone.

To be clear, I don’t think either of these scenarios are all that likely. Even if all you want to do is sit in a cave and think all day, it’s still in your best interest to defend your cave from any outsiders who might try to destroy it. And the easiest way to remove the threat of outsiders is to simply remove the outsiders. Even for non-expansionary agents, instrumental convergence applies. Nonetheless, I do not believe that misaligned superintelligence necessarily implies that AI will try to take over the whole universe.

Putting these three possibilities together, we have a 50% probability that our most powerful AI will not be a misaligned, expansionary agent. In other words, we have a 50% probability that our most powerful AI will not try to conquer the universe.

(Note that I say “most powerful AI” and not “every AI”. We can imagine a scenario in which a misaligned superintelligence tries to conquer the universe but is thwarted by a more powerful aligned superintelligence. As long as the most powerful AI is on humanity’s side, then it doesn’t really matter if less powerful AIs are aligned or not.)

8. Superalignment is a tractable problem (20%)

For those who don’t know, superalignment is the task of aligning superintelligent AI systems to their creators’ wishes. Even if AGI wouldn’t be aligned by default, some have argued, it could still become aligned with enough effort and clever engineering.

Once again, we encounter a debate where I feel like I’m in over my head. That’s because assessing the strength of any particular alignment strategy would require extensive technical knowledge of cybersecurity, along with insider knowledge of the algorithms and systems involved. I have neither, so take what I’m about to say with a grain of salt.

A lot of smart people seem to think that superalignment is tractable, but honestly, the entire effort strikes me as wishful thinking. If a being that is way smarter than you wants to deceive you or take advantage of you in some way, it will probably find a way to do so. You can write a million papers about mechanistic interpretability or scalable alignment, but it won’t fix the fundamental issue that a less intelligent creature is rarely capable of controlling a more intelligent creature. ASI, practically by its very definition, will be able to outsmart any security measures you could conceive of to contain it.

To be clear: this is not a statement against superalignment or technical safety work. I think that such work still has a reasonable chance of succeeding, and given the extremely high stakes, that still makes it worth doing. Besides, who am I to contradict Ilya Sutskever? I just think we should be realistic that superalignment is a long-shot bet that we should only rely on if absolutely necessary.

9. Once we solve superalignment, we’ll enjoy peace (80%)

At this point, we should probably define what we mean by a “good AI future”. Some people believe that AI development will go well if humans remain in control of AI, whereas others believe that AI development will go well if it leads to human prosperity. These might sound like synonymous conditions, but they really aren’t.

Gradual disempowerment is the idea that even if we create an aligned superintelligence that does whatever it’s told, it will become increasingly difficult for humans to exercise meaningful control over that superintelligence. The AI will move too fast and be too complicated for us mere humans to keep up with, so realistically the AI will still be able to mold the world however it wishes. Maybe the AI will have even mastered the art of persuasion, such that even if it technically only does what we tell it to, it can manipulate us to give it whatever orders that it wants us to give. This seems…fine to me. I’m a total utilitarian, so the only thing I care about is whether humans (and other sentient beings) feel pleasure or pain. I don’t care if the AI controls us, as long as it uses the control to benefit us rather than harm us. I recognize, of course, that not everybody shares my moral beliefs. Some people think that human autonomy is an inherently good thing, and such people would reject having AI overlords, even if those overlords are benevolent. But I think that for those of us with a utilitarian worldview, as long as the ASI is aligned, we have no reason to worry about gradual disempowerment.

There is an additional concern that even if some humans remain in control of AI, those humans won’t necessarily act in the best interests of other humans. For instance, many have written about stable totalitarianism, the idea that technology could enable a regime to permanently entrench its control over some or all of humanity and stomp out all opposition. Whereas any human dictator can only live for so many years, the thinking goes, a digital dictator could live forever. I agree that this is a cause for some concern, but I’m not too worried about it. One crucial reason why the totalitarian regimes of the past were so bad is resource scarcity; there was only so much wealth and land to go around, and leaders were willing to use extreme acts of violence to make sure that their preferred group had access to those resources, while other groups did not. But if you get rid of resource scarcity, there’s suddenly not much to fight about. Assuming that ASI can lead us into a universe of abundance, then even the most greedy and cold-hearted dictator will be able to fulfill his wishes without resorting to oppression. The techno-Nazis won’t need wars of conquest to win their lebensraum; they can just colonize other planets. The techno-Stalinists won’t need to steal from kulaks in order to feed the people; they can just build giant robot factories, thus finally fulfilling the Marxist ideal of giving “to each man according to his need”. As stated before, I’m fine with having an overlord, as long as that overlord treats me well.

But – some might argue – just having material abundance doesn’t guarantee a good or free life. We can imagine a techno-ISIS controlling their techno-caliphate, covering women in hijabs made of silicon, and forcibly inserting chips into each person’s brain to track whether they’ve oriented their hoverboard to face Mecca 5 times today. This techno-caliphate might have solved poverty and hunger, but it would still seem like a dystopia to most of us. Thankfully, our leading AI labs seem to be mostly free from religious extremists – if anything, atheists are highly overrepresented among AI developers – so this particular scenario seems farfetched. But what about other authoritarian ideologies? I’ve written before about what might happen if the Chinese government creates ASI. The tl;dr is that I am worried about the possibility and would not want to trust the CCP with ASI; but nonetheless, modern Chinese technocrats seem far more interested in building high-speed rails than in conducting the cultural purges of their Maoist forebears.

Others have brought up the possibility that instead of there being just one ASI, there might be multiple rivalrous ASIs. These rivalrous ASIs might go to war with each other, with humans as the collateral damage. This seems…way too speculative for me to even comment on. We’ve strayed pretty far from the path of anything quantifiable, and what happens after we build ASI is ultimately a matter of pure guesswork. I’m just going to say that, conditional on humanity creating an aligned superintelligence, a utopian future will follow with 80% probability. That 80% figure is based on nothing but vibes, but that’s about the best I can do.

10. Unaligned ASI will spare us (1%)

Even if AI is misaligned and tries to control the universe (per claim 7), some have argued that it will spare the planet Earth and all the humans on it. These arguments, however, strike me as very implausible wishful thinking.

Perhaps, some might claim, the AI will keep us around to do trade with us. I mean, maybe. But it’s hard for me to imagine what goods or services a human could provide that a galaxy-conquering ASI couldn’t get on its own. And even if we somehow could produce some good or service that the AI can’t get elsewhere, the result wouldn’t be the AI leaving us alone and mutually cooperating; the result would be the AI enslaving us and forcibly harvesting our resources for perpetuity. I guess that’s not doom per se – it’s only permanent enslavement rather than death – but it sure doesn’t seem like a fun scenario for us humans.

Or perhaps, some might claim, the AI will keep us around to study us, just as we keep some wild animals around on nature reservations. But again, it’s hard for me to imagine what an AI could possibly learn about us that it couldn’t have learned from studying the hundreds of thousands of years of human history, or from running realistic simulations of human life.

The way I see it, if there really is a superintelligence that is bent on conquering the universe and doesn’t listen to humans, then the chances are overwhelmingly high that humans won’t fare very well.

11. AI doomerism is bad epistemology (true, but mostly irrelevant)

Trying to predict the future of technology is inherently an epistemically fraught thing to do. This is especially true in the case of AI, for several reasons: AI is a very new and speculative technology; it's not clear who, if anybody, should be considered an expert on forecasting AI; and AI forecasting relies on insights gleaned from many disparate disciplines (computer science, mathematics, materials sciences / semiconductor physics, economics, history, and even philosophy). It's hard to be truly knowledgeable about even one of these areas, and being knowledgeable enough to make accurate predictions across each of those disciplines seems practically impossible. It's important to be epistemically humble in moments like this.

That being said, “We’re bad at predicting the future” doesn’t really update us in one direction or the other. AI doomers face the exact same epistemic problems as non-doomers, so this isn't a good argument either for or against doom.

If it's an argument for anything, it's an argument against both very high p(Doom) numbers and very low p(Doom) numbers. If somebody claims that AI doom is <1% likely or >99% likely, then I think they're being overconfident in their ability to predict the future. But within the 1-99% doom range, I don't think this heuristic helps us very much.

Multiplying the Numbers Together

So, considering everything I’ve said above, what’s my P(doom)?

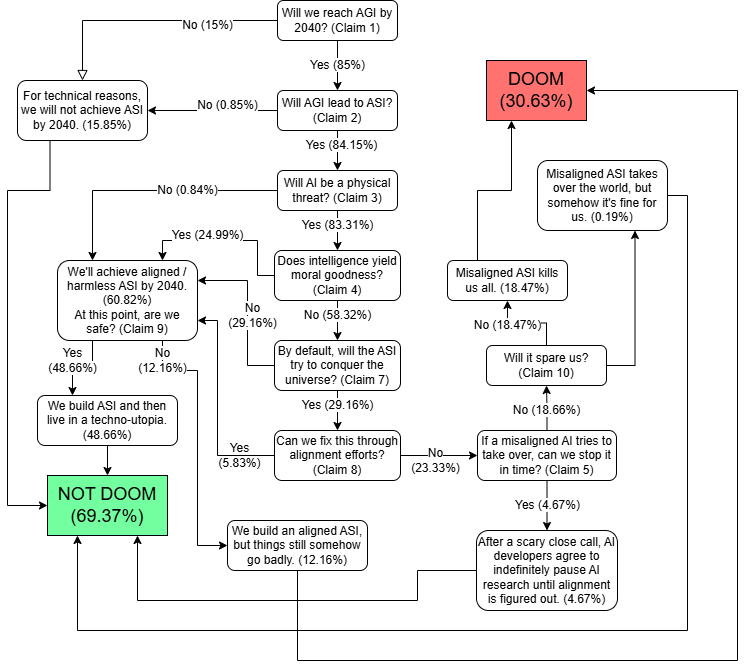

Per the flowchart above, my baseline P(doom) is 30.63%.

Other Considerations

Everything I’ve written above is my attempt to construct, from first principles, a reasonable prior about the likelihood of AI doom. But on top of that prior, there are various other heuristics / pieces of evidence we can use to update our beliefs upward or downward. In my estimation, the most important of these include:

“Humanity Won’t Be Doomed” is a Good Historical Heuristic

There is no shortage of people throughout history forecasting the doom of humanity. These people range from religious eschatologists, to Malthusians, to those forecasting the inevitable rise of global totalitarianism, to those believing that nuclear weapons will kill us all, to extreme climate change pessimists. You may believe that these claims are plausible or not, but at least as of June 2025, none of these doomsday predictions have come true.

This suggests that as a rule, humanity is actually pretty good at avoiding dangers, innovating our way out of our greatest problems, and leaving an intact world for our children. If you walk through life with a “Nothing Ever Happens” attitude, you’ll be correct far more often than you’ll be incorrect.

Therefore, I’d give this a Bayes factor of 0.75. It lowers my P(doom), but I think it’s too broad a statement to update very greatly on. (Also, it should be noted that there is some survivorship bias here: If any of those previous catastrophic risks had killed humanity, then we wouldn’t be alive today to think about them. By definition, we can only live in a universe where humanity hasn’t gone extinct.)

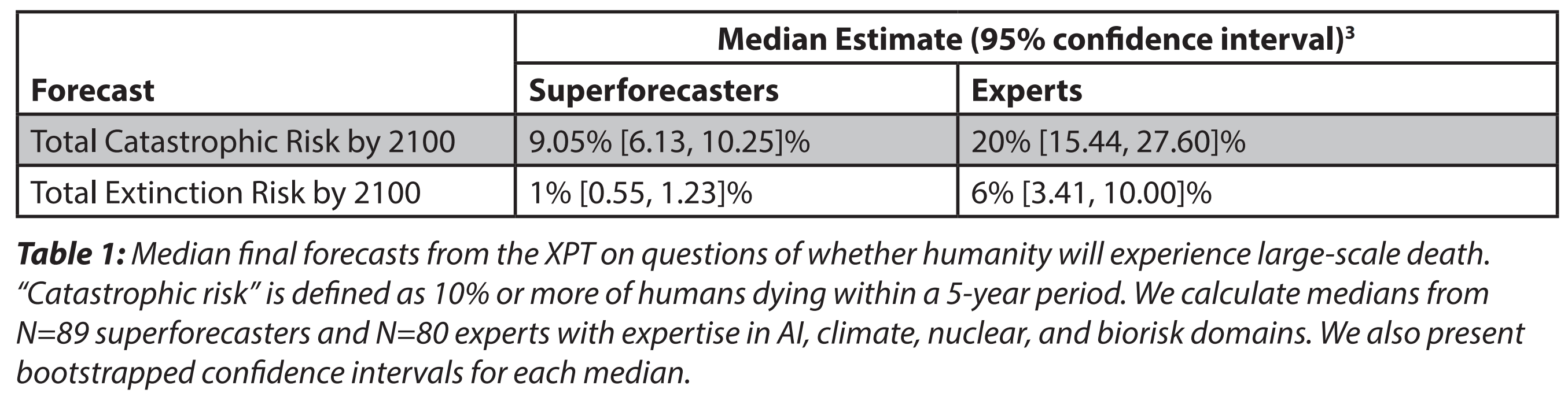

Superforecasters Think We’ll Probably Be Fine

If you want to know how the future will go, why not ask the experts at future-prediction? There are multiple websites and venues where forecasters can compete to see who’s the best at predicting the future; the winners of these competitions are known as superforecasters. I won’t go into the exact details of how superforecasters are identified (there’s a whole book about it if you’re curious), but suffice it to say that these are incredibly impressive people who have a very good track record at predicting future events (at least compared to non-superforecasters, and even compared to many domain experts).

What do the superforecasters say? Well, the most comprehensive effort to ascertain and influence superforecaster opinions on AI risk was the Forecasting Research Institute’s Roots of Disagreement Study.[2] In this study, they found that nearly all of the superforecasters fell into the “AI skeptic” category, with an average P(doom) of just 0.12%. If you’re tempted to say that their number is only so low because they’re ignorant or haven’t taken the time to fully understand the arguments for AI risk, then you’d be wrong; the 0.12% figure was obtained after having months of discussions with AI safety advocates, who presented their best arguments for believing in AI x-risks.

(This is not to say that there aren’t any superforecasters who believe in AI x-risks. Eli Lifland, co-lead of the famous Samotsvety Forecasting team and author of AI 2027, is one of them. But such people appear to be a minority of the superforecaster population.)

If my estimate of P(doom) is markedly different from the superforecasters’ estimates, then at least one of us has to be wrong. And between me and the superforecasters, I’m epistemically humble enough to think that the mistake is probably on me.

Therefore, I’d give this a Bayes factor of 0.2. Sure, it’s possible that I’m right and the superforecasters are wrong. Maybe AI is such an unprecedented development that the superforecasters’ intuitions are all wrong, or they’re suffering from groupthink, or they simply lack the requisite technical knowledge to come to an accurate opinion. But if the superforecasters can’t be trusted to find a good answer, why should I believe that anybody else can? This is, to my knowledge, the strongest argument against AI doom.

AI Developers and Top Government Officials Seem to Think We’ll Be Fine

Who has the most advanced technical knowledge, and who has access to top-secret information about today’s cutting-edge AI technologies? Well, the AI developers themselves! And, to a lesser extent, American and Chinese government officials. If anybody is in a position to accurately assess the state of AI and the risks it poses, it should be these people. If anybody were to see warning signs of a coming misaligned agent, it would be these people. And so, do they see a risk?

By any outward indications, no. AI companies are still rushing forward at full speed, saying and doing little to indicate that they believe seriously in AI x-risks. (The only exception among company heads seems to be Dario Amodei, who does talk about AI risks pretty regularly.) Government officials also seem to be largely silent on the matter, focusing instead on economic growth and competition with China. Sure, some politicians will talk about mundane AI risks like deepfakes or job loss, but they won’t touch the big issue.

Now, you might reasonably protest that these are not exactly unbiased sources. AI companies are incentivized to downplay risks in order to obtain short-term economic gains. And politicians are incentivized to ignore existential risks (which are seen as a fringe and faraway issue) in favor of more salient and quotidian political concerns. But even though AI developers and government officials might be biased, they’re not suicidal. I think that if Sam Altman truly believed that AI would kill him and his child and everyone else he loves, he would pull the plug. And if President Trump believed that AI would kill him and his children and everyone else he loves, he too would pull the plug.

Since the AI developers and government officials are not pulling the plug, it seems accurate to say that they genuinely believe that AI poses no significant existential risks, or at least that such risks are manageable. And once again, I’m epistemically humble enough to not presume that I know more about AI risk than the engineers at OpenAI.

Of course, it should also be noted that even if AI developers genuinely believe their own rhetoric about AI safety, that doesn’t necessarily imply that the rhetoric is true. People frequently come to false beliefs in situations like this, for a number of reasons. People are notoriously bad at taking low-probability, high-impact risks seriously, even when they affect them personally (see: climate change, pandemic preparedness). There's a well-documented psychological bias toward optimism about risks from technologies you're personally involved in developing. And there’s the "boiling frog" problem - if risks emerge gradually, they might not trigger the dramatic "pull the plug" response you'd otherwise expect. Nonetheless, it is substantially more likely that AI developers would believe that what they’re doing is safe conditional on it actually being safe than conditional on it being dangerous.

Therefore, I’d give this a Bayes factor of 0.6.

Multiplying the Numbers Together (Again)

Taking my baseline P(doom) number and multiplying it by each of the bayes factors gives .3063 x .75 x .2 x .6 = .0276. In other words, after all my analysis is complete, I believe that there is a 2.76% chance that AI will doom humanity by the year 2040.

Conclusion

A 2.76% probability of AI doom is fairly low by the standards of the AI safety community, but it’s not trivially low. It still means that there is a 2.76% chance that you and everybody you love will be dead in the next 15 years. We should lower those odds if we can! You don’t have to be a doomer to support AI safety.

Before writing this post, I had believed that P(doom) was somewhere in the range of 1-5%, and my updated belief falls right in the middle of that range. Of course, you should be skeptical whenever somebody produces a lengthy tract of “evidence” in favor of something they already believed, since that is a red flag for confirmation bias. But I promise that I did not write this post with the intention of confirming my pre-existing beliefs. I wrote this post in a genuine effort to find the truth, and I started with my mind open to the possibilities that the real P(doom), after calculating, could be substantially higher or lower than I expected. Maybe I did something wrong, or maybe I got lucky, or maybe I just have really good gut intuitions for things like this.

I am not confident that I came to the right answer. There are many points where I am out of my depth, where some very smart people disagree with me, and where I relied on vibes and guesswork rather than any serious argument. I’m writing this not because I believe I’ve generated some novel insight into the nature of AI risk, but because I think it is useful for both myself and others to know exactly where I stand and why.

I encourage my readers, especially if you disagree with me, to produce your own version of this document with your own thoughts and probabilities. On which of the 11 claims do you most disagree with me? What other factors would you use to update your beliefs one way or the other? What might I be missing?

- ^

I’m not claiming that the highest IQ is 200 (it’s basically impossible to reliably measure IQ above a certain point), nor am I claiming that IQ is a perfect measure of intelligence. I’m just using the example to make my point clear.

- ^

This study was conducted from April - May 2023. Obviously a lot has changed in the AI world since then, but afaik the headline results of this study have not been substantially altered by recent events. If anybody can point me to a more recent study regarding superforecasters’ AI x-risk estimates, I’d love to see it.

I see this a bunch but I think this study is routinely misinterpreted. I have some knowledge from having participated in it.

The question being posed to forecasters was about literal human extinction, which is pretty different from how I see

p(doom)be interpreted. A lot of the "AI skeptics" were very sympathetic to AI being the biggest deal, but just didn't see literal extinction as that likely. I also have moderate p(doom) (20%-30%) while thinking literal extinction is much lower than that (<5%).Also the study ran 2023 April 1 to May 31, which was just right after the release of GPT-4. Since then there's been so much more development. My guess is if you polled the "AI skeptics" now, the p(doom) will have gone up.

Bostrom defines existential risk as "One where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential." There's tons of events that could permanently and drastically curtail potential without reducing population or GDP that much. For example, AI could very plausibly seize total power, and still choose to keep >1 million humans alive. Keeping humans alive seems very cheap on a cosmic scale, so it could be justif... (read more)