Here’s the funding gap that gets me the most emotionally worked up:

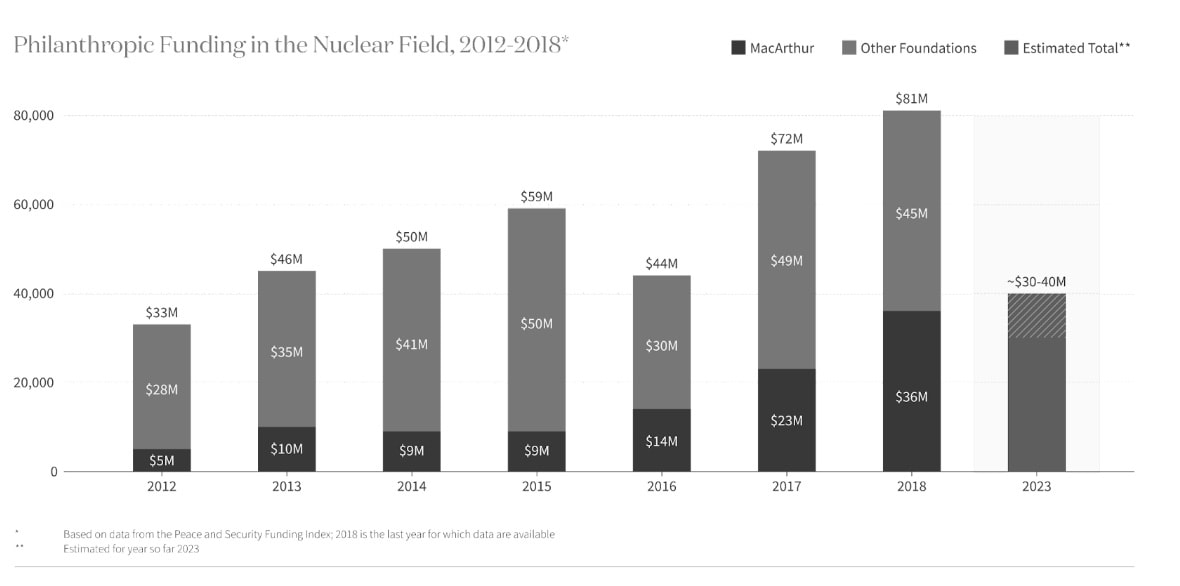

In 2020, the largest philanthropic funder of nuclear security, the MacArthur Foundation, withdrew from the field, reducing total annual funding from $50m to $30m.

That means people who’ve spent decades building experience in the field will no longer be able to find jobs.

And $30m a year of philanthropic funding for nuclear security philanthropy is tiny on conventional terms. (In fact, the budget of Oppenheimer was $100m, so a single movie cost more than 3x annual funding to non-profit policy efforts to reduce nuclear war.)

And even other neglected EA causes, like factory farming, catastrophic biorisks and AI safety, these days receive hundreds of millions of dollars of philanthropic funding, so at least on this dimension, nuclear security is even more neglected.

I agree that a full accounting of neglectedness should consider all resources going towards the cause (not just philanthropic ones), and that 'preventing nuclear war' more broadly receives significant attention from defence departments. However, even considering those resources, it still seems similarly neglected as biorisk.

And the amount of philanthropic funding still matters because certain important types of work in the space can only be funded by philanthropists (e.g. lobbying or other policy efforts you don't want to originate within a certain national government).

There's also almost no funding taking an approach more inspired by EA, which suggests there could be interesting gaps for someone with that mindset.

All this is happening exactly as nuclear risk seems to be increasing. There are credible reports that Russia considered the use of nuclear weapons against Ukraine in autumn 2022. China is on track to triple its arsenal. North Korea has at least 30 nuclear weapons.

More broadly, we appear to be entering an era of more great power conflict and potentially rapid destabilising technological change, including through advanced AI and biotechnology.

The Future Fund was going to fill this gap with ~$10m per year. Longview Philanthropy hired an experienced grantmaker in the field, Carl Robichaud, as well as Matthew Gentzel. The team was all ready to get started.

But the collapse of FTX meant that didn’t materialise.

Moreover, Open Philanthropy decided to raise their funding bar, and focus on AI safety and biosecurity, so it hasn’t stepped in to fill it either.

Longview’s program was left with only around $500k to allocate on Nuclear Weapons Policy in 2023, and has under $1m on hand now.

Giving Carl and Matthew more like $3 million (or more) a year seems like an interesting niche that a group of smaller donors could specialise in.

This would allow them to pick the low hanging fruit among opportunities abandoned by MacArthur – as well as look for new opportunities, including those that might have been neglected by the field to date.

I agree it’s unclear how tractable policy efforts are here, and I haven’t looked into specific grants, but it still seems better to me to have a flourishing field of nuclear policy than not. I’d suggest talking to Carl about the specific grants they see at the margin (carl@longview.org).

I’m also not sure, given my worldview, that this is even more effective than funding AI safety or biosecurity, so I don’t think Open Philanthropy is obviously making a mistake by not funding it. But I do hope someone in the world can fill this gap.

I’d expect it to be most attractive to someone who’s more sceptical about AI safety, but agrees the world underrates catastrophic risks (or reduce the chance of all major cities blowing up for common sense reasons). It could also be interesting as something that's getting less philanthropic attention than AI safety, and as something a smaller donor could specialise in and play an important role in. If that might be you, it seems well worth looking into.

If you’re interested, you can donate to Carl and Matthew’s fund here:

If you have questions or are considering a larger grant, reach out to: carl@longview.org

To learn more, you might also enjoy 80,000 Hours’ recent podcast with Christian Ruhl.

This was adapted from a post on benjamintodd.substack.com. Subscribe there to get all my posts.

It's worth separating two issues:

The Foundation had long been a major funder in the field, and made some great grants, e.g. providing support to the programs that ultimately resulted in the Nunn-Lugar Act and Cooperative Threat Reduction (See Ben Soskis's report). Over the last few years of this program, the Foundation decided to make a "big bet" on "political and technical solutions that reduce the world’s reliance on highly enriched uranium and plutonium" (see this 2016 press release), while still providing core support to many organizations. The fissile materials focus turned out to be badly-timed, with Trump's 2018 withdrawal from the JCPOA and other issues. MacArthur commissioned an external impact evaluation, which concluded that "there is not a clear line of sight to the existing theory of change’s intermediate and long-term outcomes" on the fissile materials strategy, but not on general nuclear security grantmaking ("Evaluation efforts were not intended as an assessment of the wider nuclear field nor grantees’ efforts, generally. Broader interpretation or application of findings is a misuse of this report.")

Often comments like the ones Sanjay outlined above (e.g. "after throwing a lot of good money after bad, they had not seen strong enough impact for the money invested") refer specifically to the evaluation report of the fissile materials focus.

My understanding is that the Foundation's withdrawal from the field as a whole (not just the fissile materials bet of the late 2010s) coincided with this, but was ultimately driven by internal organizational politics and shifting priorities, not impact.

I agree with Sanjay that "some 'creative destruction' might be a positive," but I think that this actually makes it a great time to help shape grantees' priorities to refocus the field's efforts back on GCR-level threats, major war between the great powers, etc. rather than nonproliferation.