We’re pleased to announce that we’ve added a new cause area to our Global Health and Wellbeing portfolio: Global Public Health Policy.

The program will be overseen by Santosh Harish, Chris Smith, and James Snowden. Santosh will lead the majority of grantmaking for the program.

We believe that some of the most important global health problems can be addressed cost-effectively by working with governments to improve policy. Policies like air quality regulations, tobacco and alcohol taxes, and the elimination of leaded gasoline have saved and improved millions of lives.

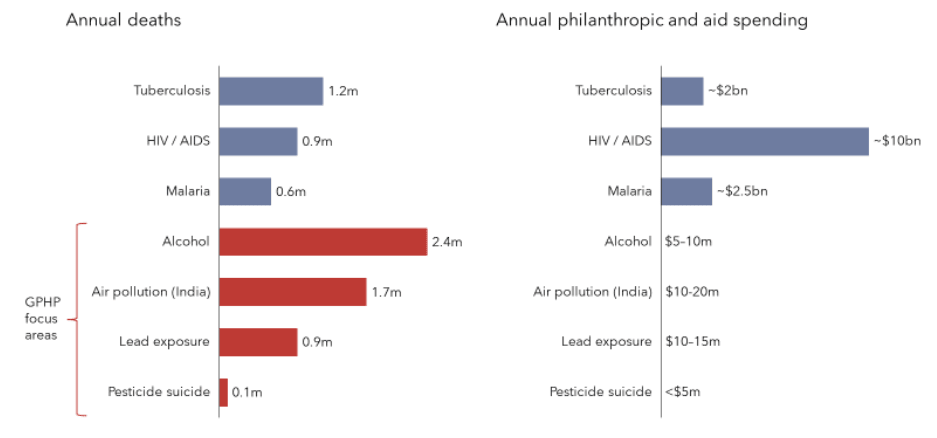

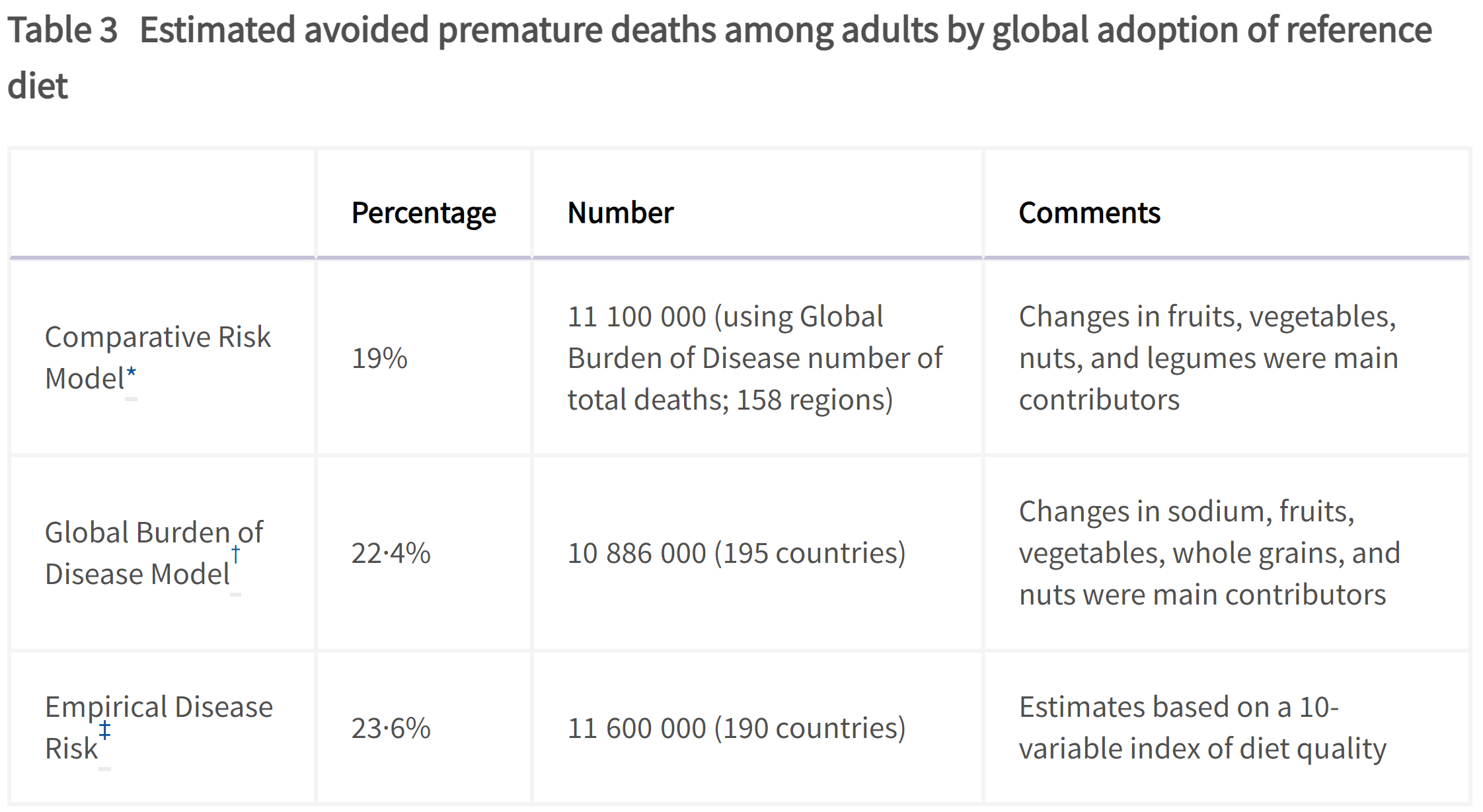

These policies typically improve public health by addressing risk factors to alleviate the burden of non-communicable disease, which comprises a growing share of the health burden but receives relatively few resources. Policy interventions affect entire populations and are often cost-effective for governments to implement. We think philanthropy can have an outsized impact by helping governments design, implement, and enforce more effective public health policies.

We’ve already made some grants for related work:

- Grants in our South Asian air quality program (which is now part of our Global Public Health Policy program)

- Several grants aimed at reducing lead exposure and excessive alcohol consumption

- Funding for the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention, to support work aimed at reducing deaths from the deliberate ingestion of pesticides

The chart below shows how little funding goes to address our current global public health policy focus areas relative to their estimated burden:

Sources: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; Mew et al. 2017; Open Philanthropy estimates

This program represents a consolidation and expansion of previous grantmaking from both Open Philanthropy and GiveWell (which incubated Open Philanthropy, and still works closely with us).

Open Philanthropy launched a program focused on South Asian air quality in January 2022, led by Santosh Harish. In October 2023, we expanded the scope of the program to include lead exposure, alcohol policy, and suicide prevention, building on a portfolio of grants which were recommended to Open Philanthropy by GiveWell.

These four topics are our current focus, but in the future we may explore other large health burdens addressable through public health policy such as tobacco, asbestos, and exposure to other pollutants.

We believe our grants to date have already resulted in meaningful impact, and we’re very excited for the potential of this new area. For more details, see the area page. And if you’d like to get in touch with us for any reason, please comment here or email info@openphilanthropy.org.

Thanks for the thoughts Kartik!

(Speaking for myself; the 10% estimate comes from work I did at GiveWell but others at Open Phil and GiveWell may disagree with me)

I agree we shouldn’t dismiss consumer surplus entirely, and in retrospect would soften some of the wording in that doc – I think the irrationality point is important but not totalizing. The Nielsen idea is interesting and I’d like to think about it more. I think internalities are less bimodally distributed between people than your model, which muddies the waters, but I wonder if an analysis like that could still be informative.

Fwiw the program we funded is primarily focused on taxation, which is a nice mechanism to balance a recognition of externalities / internalities with a general prior towards personal choice. I'd estimate higher than 10% if that wasn’t the case. A focus on tax means the reduced consumption will be from the drinks for which people had the lowest willingness to pay, limiting lost consumer surplus.[1] It also results in increased tax revenue, so could be considered as trading off against alternative ways of raising tax revenue with their own deadweight loss in consumer surplus.

TBC, I recognize the inherent fragility / subjectivity of the 10% estimate and I suspect different people would come to quite different conclusions about what input to use, so I’d be excited to see more efforts to estimate this considering the broad sweep of evidence.

Of the two studies I could find on consumer surplus, the one which attempted to estimate consumer surplus from a marginal increase in price (rather than for typical consumption) estimates a loss of €58 million in consumer surplus, compared to a €700m improvement in “health, productivity, and non-financial welfare losses” (Anderson and Baumberg 2010, pg 34), implying an offsetting impact of ~8%. (Though I think there are a bunch of ways in which that study isn’t analogous to the models we use, including a higher estimate of non-health impacts, so difficult to know what to make of it).

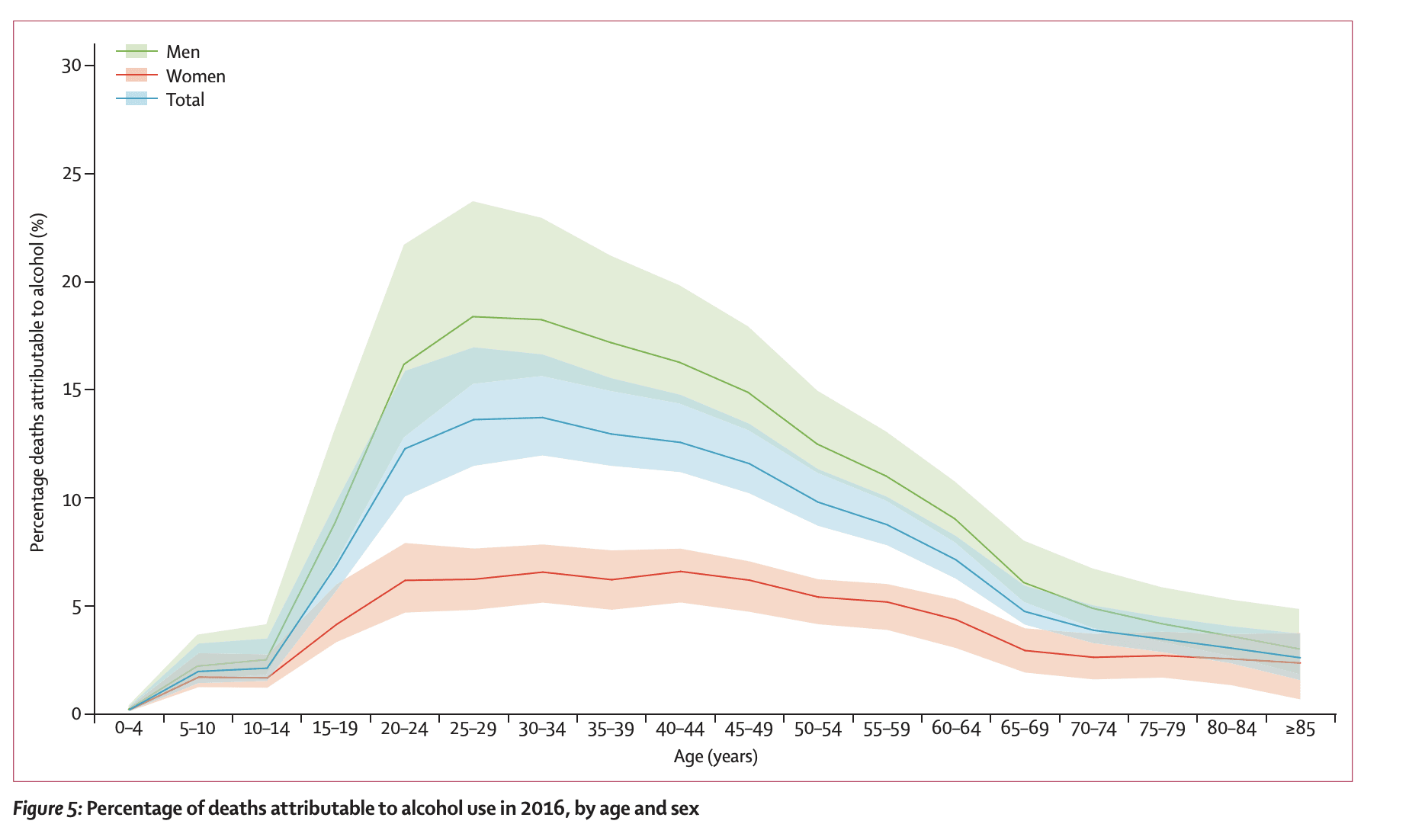

This also raises a separate worry about the extent to which taxation affects heavy drinkers, where the marginal harm is likely highest, which we tried to account for separately in the effect size estimate.