A tale of two movements

Imagine you are a student only starting to learn history, and you are presented with a case study. Two intellectual movements emerge around the same historical period, each committed to improving society and making people's lives better. Both set ambitious, seemingly radical goals that, at first, appear unlikely to succeed.

Fast-forward several decades. One movement grows to impressive proportions, establishing political parties across multiple countries, with tens of millions of disciplined members unified under a powerful international organization. One of these parties seizes control of a vast former empire rich in human and natural resources, while others subsequently govern a range of nations across different continents. The largest of these countries adopts a state emblem featuring a globe without borders, overlaid with symbols of labour and accompanied by the rallying cry for the proletariat of all nations to unite. In this bloc of countries, the official form of address becomes 'comrade', replacing traditional titles associated with inequality. Many intellectuals, artists, scientists, and politicians worldwide rally to support this movement, contributing ideas, influence, and even state secrets.

The other movement remains a loose and seemingly eclectic coalition of middle-class intellectuals, never exceeding several thousand members at its peak. Although it includes a handful of well-known names, its influence is largely confined to a single country—a former superpower in gradual decline.

Finally, you are asked: “Which movement had the greater chance of improving lives and achieving its goals?"

Any person with common sense but without knowledge of history would certainly think that the first, far more powerful movement, would certainly bring greater progress for humanity. And prove to be wrong.

The first one is the communist movement, which rose to global prominence in the 20th century. Despite its immense scale and resources, its grand promises often turned into unprecedented repression, inefficiencies, poverty, and immense human suffering, leaving a complex and tragic legacy. Immediately after the breakdown of the Soviet Union communists lost power in a whole number of satellite countries, which they had controlled due to military, economic and repressive support of the USSR.

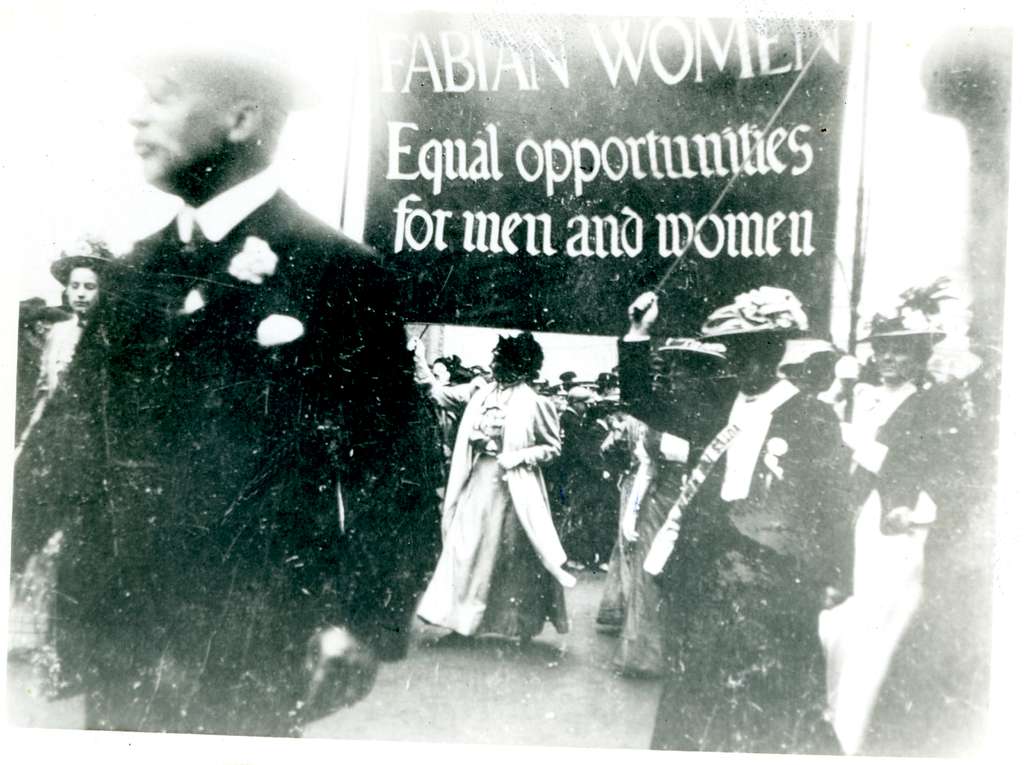

The second movement is the Fabian Society, a small, loosely organized group of British middle-class intellectuals with modest resources and often an unassuming presence. Leon Trotsky, one of the most prominent Russian communists, said of them:

“The Fabians form, in a theoretical respect, an exceedingly cloistered little world, deeply provincial, despite the fact that they live in London. Their philosophical inventions are necessary neither to the Conservatives nor to the Liberals. Even less are they necessary to the working class, for whom they provide nothing and explain nothing. These works in the final reckoning serve merely to explain to the Fabians themselves why Fabianism exists in the world. Along with theological literature this is possibly the most useless, and certainly the most boring, type of literary activity.” Leon Trotsky, The Fabian ‘Theory’ of Socialism (1925)

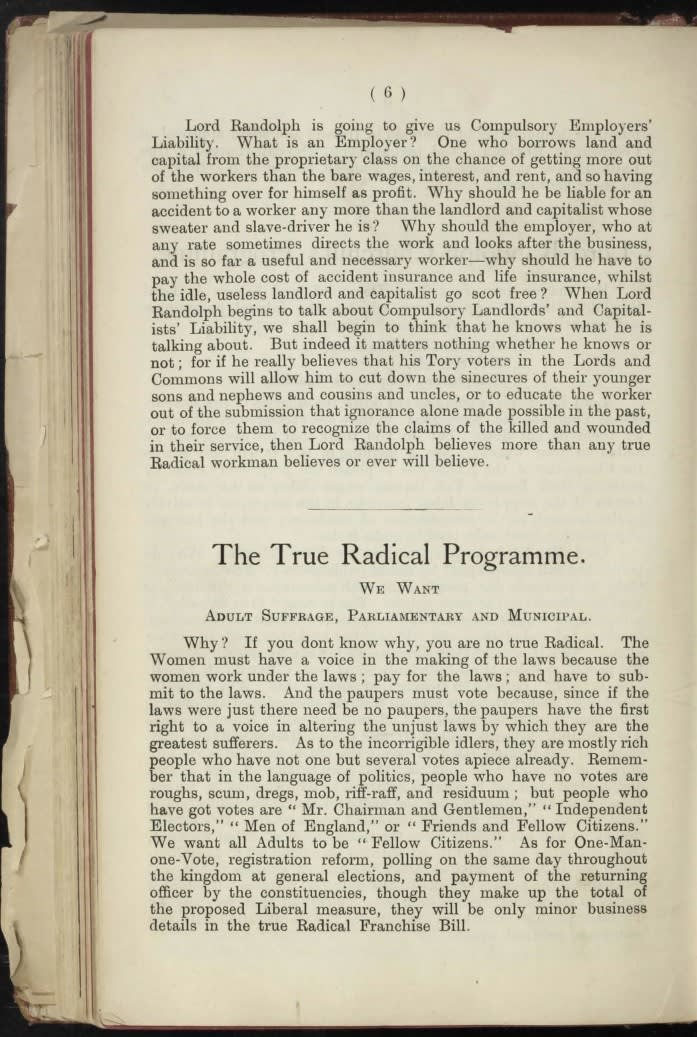

Yet, in its quiet and deliberate way, the Fabian Society achieved remarkable success. Look for example at their The True Radical Programme of 1887, which consisted of the following points:

- “adult suffrage, parliamentary and municipal”,

- paying salaries to MPs and reduction of parliamentary terms (which were 7 years at the time),

- progressive taxation on “unearned incomes” (mainly rents and interest),

- allowing elected municipal authorities to establish enterprises and compete with private companies (such as for example in supply of gas and water),

- “provision of education at public cost” and free meals “for all children at Board Schools”,

- eight hours workday.

You may ask – why call this a radical programme, aren’t these reasonable demands?

And it is a considerable extent due to the Fabians that these programme points look today like nothing special, a norm for any truly democratic society. Here is some flavour of life in the UK in 1887:

- Elections. Around 71% of the adult population did not have voting rights. No woman could vote, plus a significant part of men who did not meet certain property or income-related qualifications.

- Parliament. Members of Parliament were not salaried, effectively restricting the role to people of the ruling classes who could afford to serve without compensation for 7 years. Yes, parliamentary terms lasted up to 7 years, limiting the frequency of elections and reducing political accountability.

- Taxation was designed to place a relatively far heavier burden on the lower classes, due to indirect taxes (such as duties on everyday goods) and low or zero taxes on rents, interest and capital gains.

- Education – despite some progressive reforms, school education was compulsory only “between the ages of five and ten, though by the early 1890s attendance within this age group was falling short at 82 per cent. Many children worked outside school hours - in 1901 the figure was put at 300,000 - and truancy was a major problem due to the fact that parents could not afford to give up income earned by their children. Fees were also payable until a change in the law in 1891. Further legislation in 1893 extended the age of compulsory attendance to 11, and in 1899 to 12.” There were no provisions for free meals in schools, affecting the health and concentration of children from impoverished backgrounds.

- Working Hours - the typical workday often exceeded 10 hours, with 6-day workweeks being standard in many industries. Workers, including women and children, faced gruelling schedules with minimal labour protections, leading to widespread fatigue and health issues.

No wonder that in 1887, quoting a modern book review, the Fabians’ True Radical Programme seemed like a set of “totally insane fringe demands”. The Programme’s opening sentence was:

“We want adult suffrage, parliamentary and municipal. Why? If you don’t know why, you are no true Radical”.

These programme goals, once considered radical, were eventually realized, fundamentally reshaping society in democratic and lasting ways. A book review notes that the Fabians’ manifesto reads like a description of the average modern democracy’s public policies.

This does not include other significant outcomes of their activity, such as for example:

“The studies made by Fabians of colonial and imperial problems, together with their personal contacts with many of the future leaders from the colonial areas have considerably influenced the development of the emerging nations.”[1]

One of the seven Fabian Essayists, Annie Besant, later in 1917 became the first female president of the Indian National Congress and in the modern India there are parks and roads named after her. Mahatma Gandhi was a member of the Fabian society during his London years and his thinking was influenced by it. During the interwar period, the Society also attracted expatriate nationalists such as Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan; Obafemi Awolowo, a key figure in Nigeria’s independence movement and its first premier of the Western Region; and Lee Kuan Yew, who later became the founding Prime Minister of Singapore. The Fabian worldview left a major impression on the constitutions and governance models of these emergent Commonwealth nations, demonstrating the Society's influence beyond Britain.

But probably their greatest achievement, as described by a Fabian activist Margaret Cole, was this:

“What, lacking a theology, were they endeavouring to urge upon British opinion, and how far were they successful? To put it as simply as possible, the Fabians were answering the question asked in the first Tract, Why Are the Many Poor? with the assertion that they need not be, and that concerted action by society as a whole could prevent it. They began their propaganda at a time when it was a general opinion that poverty was an inescapable fact of society, destitution a reasonable consequence of a person's own faulty character, and unemployment, for the most part, a form of malingering which could be stopped if the penalties were made sufficiently deterrent. Today, nobody – or hardly anybody – believes that any longer; and the disappearance of the belief can without hesitation be ascribed in great part to the persistent propaganda of Fabians over the years. … But to diagnose evil is not to cure it; and the merit of Fabian reformers is that they went on to press for the abolition of great tracts of poverty by specific action – through a system of social security above all, but also through such lesser measures as provision of dinners and milk for schoolchildren and of public housing of reasonable standard, through reduction of hours of work and improvement of factory conditions, through wage regulation for the underpaid and fair wages clauses in local authority and government employment. All these today are commonplaces...”[2]

Major success factors

What factors were behind the success of the Fabians? There were certainly quite a few of them. Some were circumstantial, such as for example having first-mover advantage by being the first socialist society in Britain. Others were planned and well-executed, such as for example the role of expensive stationery. [3]

I would list three success factors being from my point of view the main ones.

People.

Dedicated and talented people were undeniably number one factor, though this was, to some extent, a stroke of luck. As Edward Pease, one of the Society’s founders, observed in The History of the Fabian Society:

“The … chief reason for the success of the Society was its good fortune in attaching to its service a group of young men, then altogether unknown, whose reputation has gradually spread, in two or three cases, all over the world, and who have always been in the main identified with Fabianism. Very rarely in the history of voluntary organisations has a group of such exceptional people come together almost accidentally and worked unitedly together for so many years for the furtherance of the principles in which they believed. Others have assisted according to their abilities and opportunities, but to the Fabian Essayists belongs the credit of creating the Fabian Society.”[4]

However, apart from that initial “good fortune”, the Fabians’ approach to cultivating human resources was far from accidental. They clearly recognized that “… people can only work together efficiently when they know each other.”

To foster and promote collaboration, the Fabians actively organized various events: regular lectures, debates, “conferences on special subjects” and “functions of all sorts in order to bring together their numbers under such conditions as enable them to become personally acquainted with each other.”

An important activity were summer schools:

Part of the intellectual potential of the Fabians was no doubt due to their tolerance for diversity of views as long as participants accepted their basic vision of socialism – something that was often wrongly branded as ‘eclectism’. While communists zealously hunted and at times even physically exterminated perceived carriers of various heresies and deviations from ‘party lines’, the Fabians encouraged open debate and intellectual experimentation, allowing a wide range of perspectives to coexist within their ranks:

Such tolerance also extended to relation with other organisations – according to Pease:

Such tolerance and openness not only attracted individuals with diverse talents and insights but also fostered a culture of creativity and innovation, enabling the Society to adapt and refine its strategies over time.

Ideas Backed by Evidence-Based Research.

The second important success factor was that the Fabians very effectively used their formidable intellectual resources to produce convincing evidence-based research. By the standards of their time, the Fabians were pioneers in using data and detailed investigation to back up their policy ideas, thereby paving the way for the modern think-tank model.

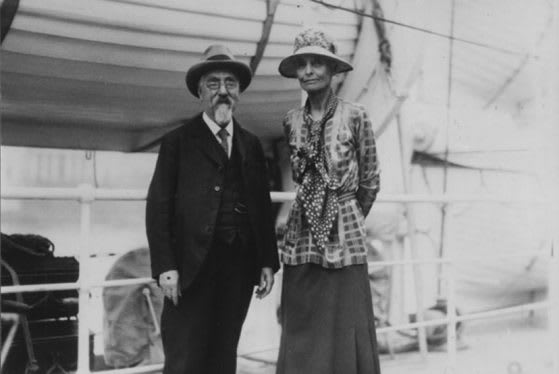

Sidney and Beatrice Webb’s major works, such as The History of Trade Unionism (1894) and Industrial Democracy (1897), weren’t just polemics—they contained meticulous statistical data, case studies, and historical analysis. They also carried out surveys, visited local councils, and interviewed officials—all of which was unusual for socialists of their time, many of whom relied more on broad theoretical arguments or purely moral appeals.

Fabian regular publications (Fabian Tracts, Essays and other pamphlets) tackled specific issues like housing, public health, education, and labour conditions. They often quoted official statistics, parliamentary reports, and other evidence to illustrate social problems and proposed solutions. In many of these tracts, the Fabians moved beyond lofty statements (“Socialism is right!”) to showing exactly how municipal ownership of gas or water could be more efficient or humane. They cited cost-benefit aspects, local precedents, and success stories, lending a heavy analytic component to their work. The New Statesman magazine, aimed at intellectual audience, was also launched by the Fabians in 1913, with G.B. Shaw being its founding director.

Sidney Webb, with the intellectual and moral support of Beatrice Webb, played a pivotal role in founding the London School of Economics. Part of their vision for LSE was to establish an institution dedicated to producing rigorous, evidence-based research. While not exclusively a Fabian institution, LSE became a center for empirical study, data-gathering, and the emerging discipline of “political science.” Its emphasis on high-quality research aligned with the Fabians’ broader ambition: to underpin social reform with robust analysis and facts—effectively championing “evidence-based governance” long before the term came into use.

Sidney and Beatrice Webb

Making Ideas a Material Force.

However, if the Fabians had only produced high-quality research, they would not have achieved as much as they did – and they understood that from the outset. To paraphrase slightly Karl Marx’s words, they recognized that ideas only become a material force once they grip the masses.

In the era without TV and internet and with the radio to become mass technology only decades later, Fabians effectively used printing press to spread their ideas. They were prolific publishers, producing a series of pamphlets known as "Fabian Tracts," which disseminated socialist ideas and policy proposals. Their first major publication, Fabian Essays in Socialism (December 1889), gained significant attention, with circulation reaching 27,000 within a year and a half—a number unprecedented for socialist publications at the time. Additionally, the society's periodicals, such as the Fabian Review, have maintained a circulation of 7,500, reaching parliamentarians, policymakers, and members throughout the country.

Part of this popularity can be attributed to the style of their publications, which were crafted to engage and persuade a broad audience. One review noted: “… propaganda based on searching investigation and hard facts, and the avoidance of jargon and sloganizing, distinguished Fabians from socialists of the doctrinaire or sentimental schools.”[5]

The society organized public lectures, conferences, and educational programs to engage directly with the public. These events featured prominent speakers, including George Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells, attracting large audiences and stimulating public interest in socialist ideas. For instance, in 1884, J.G. Stapleton delivered a lecture titled "Social Conditions in England with a View to Social Reconstruction or Development" , marking the beginning of a long series of Fabian fortnightly lectures.

One well-known and particularly effective part of the Fabians' strategy was “permeation.” This term, as described by Margaret Cole, referred to the practice of influencing individuals or groups in positions of power or influence, rather than seeking direct political control. The Fabians aimed to “honeycomb” society with their ideas, ensuring that key decision-makers—whether politicians, civil servants, industrial leaders, or academics—were taking into account Fabian ideas, even if they were not formally affiliated with the Society. The ambition was grand:

“One gets, sometimes, an impression of a Fabian vision of Britain in which every Important Person, Cabinet Minister, senior civil servant, leading industrialist, University Vice-Chancellor, Church dignitary, or what-not, would have an anonymous Fabian at his elbow or in his entourage who, trained very thoroughly (maybe in the Webbs' ideal School of Economics) in information, draughtsmanship, and the sense of what was immediately possible, would ensure that the Important Person moved cautiously but steadily in the right direction.” [6]

However, as Cole admits, “this vision was never fulfilled, of course.” Despite this, the Fabian strategy of quiet influence had a measurable impact on policy and institutions.

Although the grandest visions of permeation were never fully realized, the Fabians effectively applied this strategy in several key areas. Here are just three examples of how permeation was able to embed their ideas in the fabric of British political and social life.

1. The Labour Party

While the Fabians didn’t achieve the sweeping vision of embedding advisors everywhere, they played a foundational role in shaping the Labour Party. Their ideas heavily influenced the party’s early platform and continued to guide its policies for decades. Notably, the Fabians had major influence “in the drafting of the Labour Party’s new constitution and long-range socialist program in 1918”[7] . Over the years, several key Labour leaders and future prime ministers were associated with the Fabian Society, including Clement Attlee, who oversaw the creation of the post-war welfare state, and Tony Blair, who led the party’s modernization under the "New Labour" banner in the 1990s.

2. Influence on the London Education Act of 1902

The Fabian Society's permeation strategy is exemplified by their involvement in shaping the London Education Act passed by Balfour’s Conservative government in 1902—a government that was decidedly not socialist. The Fabians publicly claimed credit for the 'unsectarian demands' and 'amendments' incorporated into the Act, which aimed to make education more accessible and secular. Their influence on the legislation was so substantial that some commentators criticized it as 'Tory Fabianism.'

This is not the only case where influence of the Fabians extended beyond the Labour Party. Many reforms associated with the Liberal government of David Lloyd George, such as the 1908 Old Age Pensions Act and the 1911 National Insurance Act, echoed Fabian proposals.

3. The London School of Economics (LSE)

The founding of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in 1895 is one of the most significant examples of the Fabian Society's permeation strategy. Sidney and Beatrice Webb envisioned the LSE as a place to train future civil servants, policymakers, and reformers in evidence-based approaches to tackling social and economic issues.

The LSE was funded by a £20,000 bequest from Henry Hutchinson, a Fabian Society member who left the money “for the advancement of socialist causes.” It quickly became a platform for embedding Fabian ideas into public policy through the people it trained. Many of its graduates went on to hold influential roles in government and administration, helping to turn Fabian principles into practice. The school also attracted students from across the world, including future leaders like Lee Kuan Yew, the first Prime Minister of Singapore.

The LSE became not only a leading center for education and research but also, in a way, an institutional hub for Fabianism. It connected reformers, academics, and policymakers, creating a network of individuals working towards the Fabians’ vision of informed, gradual social reform. Its influence on policymaking and governance remains one of the clearest examples of how the Fabians used permeation to embed their ideas deeply into society.

Lessons for EA

Writing about the Fabians, I wanted to build on the theme from my earlier post about communities that achieved an outsized impact on humanity relative to their size.

What lessons can EA draw from the experience and history of the Fabians? First, one must note that there are similarities between the Fabians and EA, and these similarities are unlikely to be accidental. The founders of EA, being intellectuals in the British tradition, would be unlikely to overlook the history and lessons of the Fabians.

(Toby Ord clarified to me after the publication of this post: "We weren't explicitly inspired by the Fabians, but were no-doubt indirectly influenced by them and by common influences, such as academia and some kind of thoughtful, modest, and polite British sensibility.")

Both movements share a commitment to making life better and more kind. Both prioritized evidence and impact. They are characterized by a tolerance for diverse views, provided their broad basic principles are accepted. Both made membership easily accessible. Both invested in building communities of like-minded individuals through events and publications, fostering collaboration and shared purpose.

There are no grand ideas here, just a few new elements to complement the already considerable scope of EA activities.

One idea is to enhance the impact of EA conferences by inviting more prominent and famous individuals as keynote speakers. This would give the EA community a chance to engage with first-rate minds while also raising awareness of EA among intellectual, entrepreneurial, and other influential circles. Having been a member of organizing committees for several investment conferences as well as a participant, I know firsthand the impact of famous speakers, such as former U.S. Vice President Al Gore and former Federal Reserve Chairs Paul Volcker and Ben Bernanke (who at that time was chairman of President George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisers). Their presence significantly boosted conference attendance and media visibility.

Of course, as a member of conference organizing committees, I also know that the cost of inviting some keynote speakers can be a bit high unless you are an investment bank. However, I am confident that many prominent speakers sympathetic to the ideas of philanthropy could be approached. There are enough well-known people and celebrities today who are active in the fields that align with EA goals. By fostering such connections, EA could amplify its visibility and attract new allies from diverse fields.

Another idea to strengthen the EA community is to create opportunities for activists from different countries to connect in informal settings. Regional EA societies already host social events, but they are typically limited to one country. Conferences provide international engagement, but these tend be more formal. What seems to be missing are international EA retreats that combine collaboration with the enjoyment of a holiday. These retreats could offer activists the chance to meet, socialize, and collaborate in relaxed, informal settings—while also enjoying the experience of a holiday. Whether by the sea or in the mountains, these retreats could foster stronger connections and meaningful exchanges of ideas, all while giving participants a break from their routines.

Finally, I think that the biggest potential for inspiration comes from the idea of “permeation”, which can be implemented in different contexts. Here is just one example. While EA does not have explicit policy goals akin to those of the Fabians, establishing contacts with government institutions across various countries can be mutually beneficial, allowing EA to amplify capabilities of its philanthropic programmes and allowing governments to increase effectiveness of their spending. However, implementing such strategies requires patience and commitment to years of dedicated effort to cultivate meaningful relationships. Lessons must be drawn from past failures, such as the closure of the Center for Effective Aid Policy. If this project were supported with greater resources and was able to operate for longer, it would have brought tangible and lasting results.

Both the Fabian experience and my own suggest that gaining the attention of government institutions often requires comprehensive approaches. These include engaging with media, forming alliances with NGOs, and collaborating with political parties and think tanks. Developing relationships with influential academics, civil society leaders, and international organizations can also play a crucial role in creating a network of support that lends credibility and momentum to EA’s initiatives. It’s also useful to learn from the Fabians how to frame recommendations in ways that align with policymakers’ priorities and institutional goals, making them both relevant and actionable.

The remarkable story of the Fabians shows how much can be achieved by a small and determined group that sets ambitious long-term goals and plans and then pursues and executes them methodically and thoughtfully. Let’s draw inspiration from their challenging and fruitful history and apply those lessons to the challenges we face today!

- ^

H. Malcolm MacDonald, The Journal of Politics, 1962, Vol. 24, p. 770

- ^

Margaret Cole, The Story of Fabian Socialism (London: Heinemann, 1961), p. 330

- ^

- ^

- ^

P.P. Poirier, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. LXXVII, p.441

- ^

“ 'Permeation' is a peculiar Fabian term, with a very long history. It is first found in print in Herbert Bland's Fabian Essay - curiously enough, Bland was not there advocating but warning the Society against it; but the casual reference shows that it was already in common use. Occasionally it seems to mean no more than what the Americans have taught us to call 'pressure groups' - persons organised with the purpose of forcing a particular measure, a particular interest, or a particular point of view upon those in power. Beatrice Webb in 1910-11 formed, with the Fabian Society as nucleus, a group of this nature, which was called the National Committee for the Prevention of Destitution, in order to force the adoption of the Webb proposals for the abolition of the Poor Law; it failed. The Labour Representation Committee itself at its foundation came near to making itself a 'pressure group' merely; the wording of the initial resolution, 'to cooperate with any party which for the first time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interest of Labour, and ... to associate themselves with any party in opposing measures having an opposite tendency', left the possibility of such an attitude open until 1903 the Committee definitely decided to separate its membership from that of the established parties and in 1904 put together what might be called a sort of program of its own. ...

What Fabian permeation meant was primarily 'honeycombing', converting either to Socialism or to parts of the immediate Fabian programme, as set out in the continuous stream of Tracts and lectures, key persons, or groups of persons, who were in a position either to take action themselves or to influence others, not merely in getting a resolution passed, or (say) inducing a Town Council to accept one of the clauses of the Adoptive Acts, but in 'following up', in making sure that the resolution or whatever it was didn't remain on paper but was put into effect. It was not necessary that these 'key persons' should be members of the Fabian Society; often it was as well they should not; what was essential was that they should at first or even second-hand be instructed and advised by Fabians.

Hence Shaw's insistence, at the Bradford Conference, that Fabians should be free to join Liberal and Radical associations where they could push the Fabian point of view; hence the Fabian delight over the formation of the Oxford University Fabian Society, full of potential rulers of England. One gets, sometimes, an impression of a Fabian vision of Britain in which every Important Person, Cabinet Minister, senior civil servant, leading industrialist, University Vice-Chancellor, Chirch dignitary, or what-not, would have an anonymous Fabian at his elbow or in his entourage who, trained very thoroughly (maybe in the Webbs' ideal School of Economics) in information, draughtsmanship, and the sense of what was immediately possible, would ensure that the Important Person moved cautiously but steadily in the right direction. This vision was never fulfilled, of course; but the influence of hard-working, educated, burrowing Fabians was sufficiently strong and persuasive to receive handsome tribute from historians like G.M. Trevelyan and Sir Ernest Barker, whose book on Political Thought in England from Herbert Spencer to the Present Day (1915) prophesied that 'the historian of the future will emphasise Fabianism in much the same way as the historian of today emphasises Benthamism.' "

Margaret Cole, The Story of Fabian Socialism (London: Heinemann, 1961), pp. 84-86

- ^

P.P. Poirier, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. LXXVII, p. 441

ank you for this post—it looks very interesting. I’ve given it a quick skim but wanted to check in on a concern/critique I have before engaging more closely with the recommendations.

Most of the post seems dedicated to explaining why the Fabians were so successful.

However, I’m not yet convinced that they actually caused meaningful change. You begin by listing some of their goals and then highlight how many of those goals came to fruition, but that doesn’t establish their causal role in making those changes happen.

It looks like you provide two main forms of evidence for their influence:

1. Noting that they had influential members or supporters in many countries.

2. Quoting a particular supporter of the Fabians.

Unfortunately, both of these seem like weak evidence to me. The first point is fairly common—many people sign up for societies and pay lip service to their supposed importance without necessarily contributing to their impact. For example, PlayPumps (a classic Effective Altruist case of an ineffective and even counterproductive yet widely endorsed charity) had many influential supporters, but that didn’t make it effective or significant.

As for the Margaret Cole quote, it doesn’t provide much evidence either—it’s essentially just an endorsement, asserting that the Fabians were important without substantiating that claim?

To be clear, I’m not saying you’re wrong about the Fabians being influential. Rather, I think the post hasn’t yet provided strong evidence for that claim. If you were to include more comprehensive or compelling evidence, this could be a really valuable post.

Thanks a lot for your work here!

(Apologies if this seems pedantic. I think these methodological considerations are important for the effort to learn useful lessons from history though. See these posts I wrote for some related thoughts)

https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/blog/what-can-the-farmed-animal-movement-learn-from-history

https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/blog/social-movement-case-studies-methodology )

Thank you for reading my post and for the thoughtful comment — and for the links to the Sentience Institute methodology, which I found genuinely interesting.

The goal of my post was to draw lessons for the EA community from the Fabians' approach, not to provide a rigorous causal analysis of their impact — which would require considerably more space and evidence than a forum post allows. That said, I do think however the evidence for Fabian influence goes well beyond the two points you mentioned. The historical literature — Margaret Cole's The Story of Fabian Socialism, Edward Pease's History of the Fabian Society, and several academic assessments — document specific causal pathways, such as for example the Fabians' direct role in drafting the Labour Party's 1918 constitution, their documented influence on the Education Act of 1902 (passed by a Conservative government), the institutional legacy of the LSE in training generations of policymakers and researchers. These are examples of traceable policy influence.

Establishing rigorous causal attribution for social change is inherently difficult — as your own methodology work discusses so well. My post would have certainly benefited from foregrounding these specific causal pathways more clearly rather than relying primarily on references to the existing literature made in my post:

- Pease,

- Cole,

- MacDonald in the Journal of Politics,

- Poirier in Political Science Quarterly,

- Scott Alexander's post.

If I revisit this topic, I'll aim to incorporate that kind of evidence more explicitly. Thank you for pushing the analysis to be stronger — that's what makes the Forum valuable.

Dear Alex,

Fascinating read, both for the title and the topic tackled and recommendations.

So, I think that history is a very good source of ideas and of inspiration on what to do next, something which I think is neglected by the EA movement in general and its primary actors specifically - I would even argue that Toby Ord's answer to you was lukewarm at best if not just polite at worst. (though i do remember tackling a fascinating book by a historian in my first book club participation).

As for the topic, I'd like to provide some comments (these are just my ignorant comments, not to be treated as authoritative in any way). First from what I remember, some of the Fabian ideas, such as at least the vote for women, were around way before the Fabians - according to Wikipedia, "A member of the Liberal Party and author of the early feminist work The Subjection of Women, Mill was also the second member of Parliament to call for women's suffrage after Henry Hunt in 1832.[5][6]" (here's he link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Stuart_Mill ). Wikipedia does not seem to consider J.S. Mill or his predecessor Henry Hunt as a Fabian.

Furthermore, I think that in the grand scheme of historical progress, it may actually be a bit more randomly that some movements' ideas get applied and other's not, or even the extent that these ideas are 'theirs' as opposed to mostly around in the ether (or zeitgeist, in other words). So, for example, I think many of the concrete ideas you attribute to the Fabians probably overlapped with other socialist or other thinkers of the time, and on the other hand, as Ord remarks, their ways of influencing and pushing their agenda forward may have also had to do more with peculiarities of British culture (groups of gentlemen, usually rich, in a stratified society, rather than say mass revolution - even Science, a previous quintessentially British revolution in 1650, was for many years practiced and propagated only among learned Gentlemen).

As for communism, in your introduction, I'd be a bit more charitable, in recognising many of its positive ideas such as trade unions, though i wouldn't hasten to contradict the preceding paragraph of the text by remarking that maybe many of the measures suggested by Marx may have also drawn from the Zeitgeist of mid-to end of the 10th century. Also however i'd remark that it's possible for communism to have the last laugh after all as I heard some time ago that whereas in the first half of the twentieth century it was the poor and uneducated who supported it, nowadays it's also championed by many educated people in the US (think, of course in a much more constrained way, of the support for Bernie Sanders).

Anyway, History's a funny thing, so you never know what may be rediscovered later and where its random (according to me, even though that's one of the huge points of contention i have with EA doctrine - longtermism - ) walk will take us and which movements will be deemed to have influenced what in the future.

And a note on your recommendations, yeah, it sounds good to attract elites, but yeah, as a personal life-choice, i've recently decided that for my biggest passions and struggles i choose to fight, I would go with the non-elite masses - at least that's the aspiration.

Best Wishes,

Haris

Dear Haris,

Thank you for the interesting comments.

As for Toby Ord's answer, it was in a friendly personal message and I quoted part of it most relevant to the post.

Regarding that some ideas were not unique to the Fabians - you are absolutely right about Mill, one of the people who I admire. Unfortunately, at his time he was unable to do anything to implement his proposal - and I wanted to take into account not only the idea but the implementation, too.

Regarding the rest, I'll be glad to discuss all this personally.

Best wishes,

Alex

Dear Alex,

Many thanks for getting back to me, yes, I agree that having a method to actually implement your wishful revolutionary thinking is very important, and yes, that could be the base of a long and fascinating discussion i'd like to have over a glass of wine and/or good food :)

Best Wishes,

Haris

Executive summary: The Fabian Society, a small group of British intellectuals, achieved remarkable social and political reforms through evidence-based research, strategic influence of key institutions, and patient advocacy - offering valuable lessons for modern movements like Effective Altruism.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Executive summary: The Fabian Society, a group of British intellectuals, achieved remarkable social and political reforms through evidence-based research, strategic influence of key institutions, and patient advocacy - offering valuable lessons for modern movements like Effective Altruism.

Key points: