The logic of a meat tax is clear: people usually opt for the cheapest option in the supermarket, which is why governments have sometimes intervened and hiked up prices for alcohol, tobacco, and unhealthy foods before. Why not meat? But what seems like a clean and easy solution is actually quite risky — not just because it could spark massive backlash, but also because it might cause more animals to be farmed. Let’s talk about it.

The following is a crosspost from my newsletter on meat reduction strategies, More Than Meats the Eye. If you'd like to receive this newsletter, you can sign up for free here.

What is a Meat Tax?

A “meat tax“ is a controversial policy that would increase the price of meat and/or animal products for consumers or for farmers to reduce their production. It’s the same idea of a tobacco or alcohol tax: a way to guide people away from harmful behaviors without fully abolishing them (called a “Pigouvian tax”).

While they might seem like a recent concept, the idea of a meat tax goes all the way back to a 90s economics report. Reading this paper, I’m struck by how matter-of-fact the idea is presented. The author made a clear argument: high meat consumption in rich countries is unsustainable, so we should incentivize the purchases of more sustainable foods like grains, fruits, and vegetables over animal products. Boom: meat tax. (Actually, he called it a “food conversion efficiency tax”, but that mouthful only goes to show that economists should never be in charge of naming things.)

Researchers disagree on how much money a meat tax should even be — 20-60% more, 9-33% more, or even 1-100% more — but in general, most proposals I have read fall somewhere around 20-30% price hikes. Some believe taxes should be different on imports and exports, various species, or should target farmers instead of consumers. Needless to say, a “meat tax” is not one specific policy proposal, but a spectrum.

Right now, true meat taxes are theoretical in all countries but one: Denmark. Starting in 2030, farmers will have to pay 43 USD per tonne of methane their animals emit, with potential exceptions if the farmers implement more sustainable agricultural practices. This is a production-focused tax, but it may still create higher prices for consumers over time. Germany and Sweden have also publicly talked about the idea, but no implementation plan currently exists.

Meat Taxes Work…Kinda

Real-world research into taxes on alcohol, foods high in fat, salt, and sugar, and other unhealthy foods shows that taxes can reduce consumption of the targeted products. We don’t yet have real-world data on meat taxes, but economic theory and models predict they’d work. A Dutch analysis estimates that a 30% tax on meat and a 10% subsidy for vegetables would benefit the economy on the scale of over ten billion euros over thirty years due to public health and environmental benefits. Another model predicted that an average meat tax of 25% could reduce meat-related deaths by 9% and health costs by 14% — billions in savings. (Check out my earlier post on the economic benefits of a plant-based world if you want to learn more.)

Note: The vast majority of research on meat taxes has focused on Northern Europe, so we don’t know how generalizable the data is to other regions.

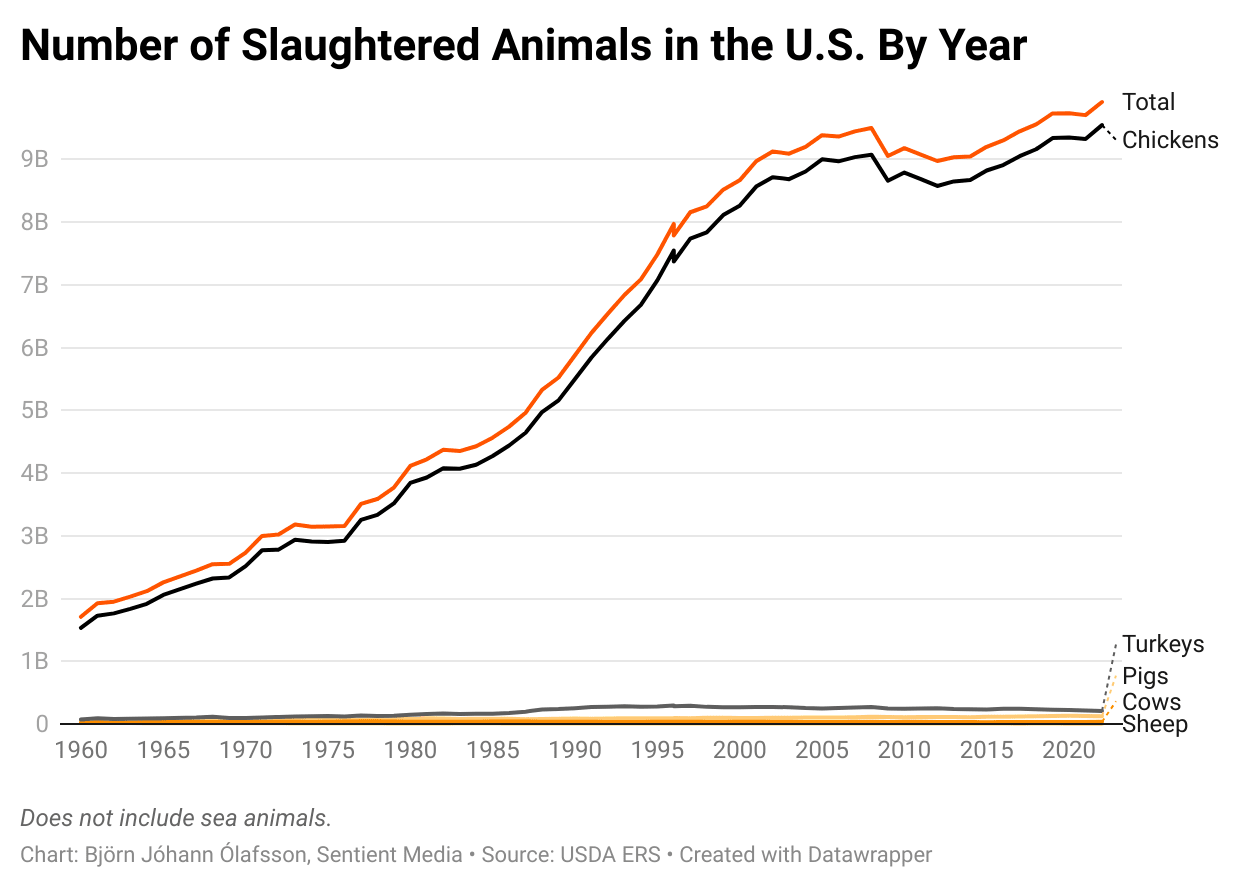

But there’s a catch. A big one. While meat taxes can probably reduce the amount of meat we consume, they might actually increase the number of animals we consume. If that sounds counterintuitive, let me introduce you to the small body problem: to get the same amount of meat from chickens as we would from a single cow, we must kill around 200 chickens, given they have, well, smaller bodies. Even if people reduce their overall meat consumption and swap some of the beef they would have eaten for chicken, the number of animals suffering in factory farms will still increase, even if everyone is eating more plants.

To help visualize the problem, check out this chart I made for an earlier article of the numbers of land animals killed in the U.S. — cows and pigs are barely a blip.

Would a meat tax make this problem worse? The research is mixed, but leans towards ‘yes’. In an excellent report from Animal Ask, Ren Ryba shows that in four out of nine studies they modelled, consumers were likely to replace red meat with chicken and/or fish. Another modelling study estimated that a red meat tax would increase poultry consumption by 5%. However, another study from this year disagrees, and models that if chicken is taxed (even if taxed less than red meat), then overall numbers of slaughtered animals would decrease.

Experiments can also help shed some light on the issue. An online supermarket experiment shows this problem in action. When participants encountered a meat tax and warning labels on red meat products, they increased their purchases of chicken by 12% and cheese by 33% compared to a control group. Plant-based meats and tofu products were unaffected. In other words, a red meat tax would likely drive people to replace beef and pork with other animal products, not plant-based foods.

Is it possible to create a meat tax that incorporates animal welfare, thereby reducing both the total consumption of meat and the number of animals in our food systems? Sure. Is it commonly talked about? Unfortunately, no. Most advocates for meat taxes tend to be motivated by climate change or public health, which are great motivations of course! But animal welfare needs to be on the agenda too.

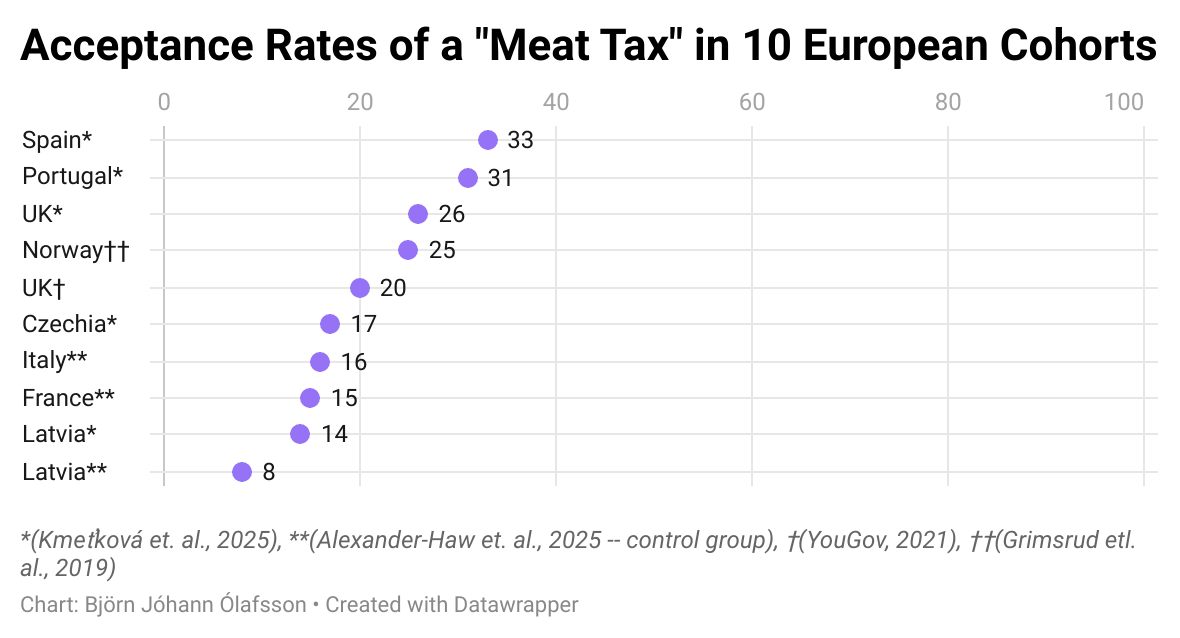

Meat Taxes Aren’t Popular

Across four studies that analyzed ten European cohorts in total, they found that the acceptance rate of meat taxes varied between 8.3% and 33%, with an average of 20.5%. That’s low. Really low. For context, no U.S president has ever polled that low, not even after January 6th or Watergate.

One reason? Equity. Focus groups have also found that people believe meat taxes may be unfair, akin to a “tax on the poor” (or, in economist terms, a “regressive tax”). Others argue, correctly or not, that these taxes would cause farmers to suffer financial harm or even bankruptcy. Some people also claim these proposals are unnecessary, harm a country’s self-sufficiency, harm biodiversity, or increase imports. And finally, the biggest downside is the most obvious: people like eating meat and don’t like spending money.

Popularity isn’t everything, of course, but research has shown that politicians tend to agree with voters on this issue more than not. It’s unlikely we could pass a law like this without moving the needle on public opinion.

Could This Change in the Future?

There is good news! Studies of meat taxes’ popularity find that they tend to be more popular amongst younger people, indicating that their popularity may grow over time. Also, when the tax is framed as lowering the prices of other foods, like fruits and veggies, politicians and citizens are more likely to support it — this can likely sidestep the argument that meat taxes are classist.

However, other research has shown that increased education on the health benefits of meat taxes doesn’t increase the odds of acceptance. Framing the tax as a boon to climate and public health only had a teeny boost in acceptance.

The name “meat tax” probably isn’t the best choice. “Food conversion efficiency tax” isn’t great either, but some people have suggested “slaughter tax,” “carcass tax,” or “methane tax”. I couldn’t find any messaging studies on the impact of different names, but I believe this could be a worthwhile area of research, similar to the Good Food Institute's efforts to label “cultivated meat correctly.”

How To Make This Work

Look, I don’t think meat taxes are an impossibility. But advocates need to tread very carefully. If we want a meat tax policy to succeed, we’d need to:

- Identify countries most likely to adopt such a tax.

- European countries are typically first on the list, but considering the lack of research in other continents, it’s worth seeing if other countries might be more open to the idea.

- Carefully design a policy such that it wouldn’t fall victim to the small body problem.

- This means that economists would need to model meat consumption in the target country and tax the production or consumption of smaller animals like chickens and fishes accordingly, not just red meat. This Pigouvian tax needs to be “Chickouvian” too.

- Ensure that the tax includes lowered prices in other food categories.

- Research suggests this is crucial for popular support — people don’t want their grocery bills to go up, so the meat tax would need to come hand-in-hand with reductions of the cost of fruits, vegetables, grains, and alternative proteins.

- Consider pairing a meat tax with other laws, such as plant-forward initiatives, farmer transition subsidies, alternative protein subsidies, or other ways to benefit both the economy and the citizens of a country.

- Consider an animal welfare tax, not just a carbon tax.

- Models suggest that a “slaughter tax” would reduce animal deaths more than a “carbon tax.”

- While nearly all the discussion of a meat tax relates to climate change (and sometimes public health), we’ve very rarely used animal ethics as a motivation. In countries with higher public support for animal welfare, these laws may be more feasible.

But good policy is only half the story. We’d need a strong messaging framework to get something like this off the ground:

- Research effective messaging and framing strategies to increase public support.

- I suspect that the most crucial narrative would be to combat the idea that a meat tax is inequitable to poor individuals and farmers.

- Other research has looked into public health vs. climate frames, but we need more experiments. Again, I think we should look more into the idea of explicitly framing this around animal welfare — this is an untapped idea.

- Message-test different names for the policy (“meat tax”, “carbon tax”, “slaughter tax”, “methane tax”, etc.).

- We need to find a name that is accurate but doesn’t stoke backlash.

- Create effective campaigning and lobbying initiatives to encourage its passage.

- Ask any advocate — nothing gets passed without consistent effort.

Passing a meat tax won’t be easy – in fact, I don’t think it should be a current priority in most countries. But it might be a good long-term goal requiring careful consideration, campaigning, and strategy. What do you think?

If you like this analysis, subscribe to my newsletter here!

Perhaps before we start thinking about a meat tax, we could think about reducing meat subsidies instead? Farm animal production, and especially production of animal feed, are hugely subsidized throughout the world.

Last I checked, the best estimates of the impact of direct subsidies on cost seemed to be around 1-2% of cost for beef and pork and less than that for chicken/eggs/milk. (Can't find this now, so lower credibility, but AI estimates seem to agree)

Based on this, removing them would be great, but probably wouldn't be tractable enough compared to other interventions given the difficulty.

I think my point is less about the impact of subsidies per se and more about what their presence tells us about the effective difficulty of taxing meat. In other words, the same political forces that give rise to these subsidies would also fight any attempt to tax meat. If you don’t think it’s realistic to end meat subsidies, then I argue you should also think it’s not realistic to start meat taxes.

I suspect that when you pose things as taxes, they almost always come out unpopular in polls. If you wanted public support you could instead lead with plant subsidy or plant based protein subsidies and then note that these would be financed by a small tax on harms to animal welfare or something.

In fact probably would do better by framing it in terms of taxing “animal-hours spent in cages”, animal pain, or factory farming in general

Executive summary: While a meat tax could reduce meat consumption and deliver climate, health, and economic benefits, poorly designed policies risk increasing animal suffering (via the “small body problem”) and face steep public opposition, so advocates should treat it as a long-term goal requiring careful policy design, strong messaging, and integration with broader food system reforms.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.