I write to raise what I think is a fundamental flaw in a Center for Global Development (CGD) article about immigration.[1] I posted here only after receiving what I considered inadequate feedback from the authors over the last 3 months.[2]

The major argument of the article “UK recruitment of nurses can be a win-win” is that the current situation where Nigeria exports an ever-increasing number of nurses to the UK could be good for both countries. For Nigeria, the benefits come through both the classic economic benefits of remittances, and stimulating increased nurse training in Nigeria to compensate for the losses of nurses.

A Misleading Datapoint

The central datapoint on which their argument rests seems misleading. The authors cite the number of nurses who leave Nigeria each year for the UK alone and claim that increased nurse training in Nigeria is enough to replace these nurses. “Between late 2021 and 2022, the number of successful national nursing exam candidates increased by 2,982—that is, more than enough to replace those who had left for the UK.” Technically, they are correct that the number trained replaces those who leave only for the UK, but they don’t consider the majority of nurses who left to other countries.

Emigration to the UK constitutes under 25% of the total nurse emigration from Nigeria. A more meaningful data point would have been the total number of nurses that leave Nigeria for all countries. Based on this Guardian article (and others), about 29,000 new nurses were registered in Nigeria over the last 3 years, while 42,000 left. The total number of nurses in Nigeria is reducing, not increasing as they claim.

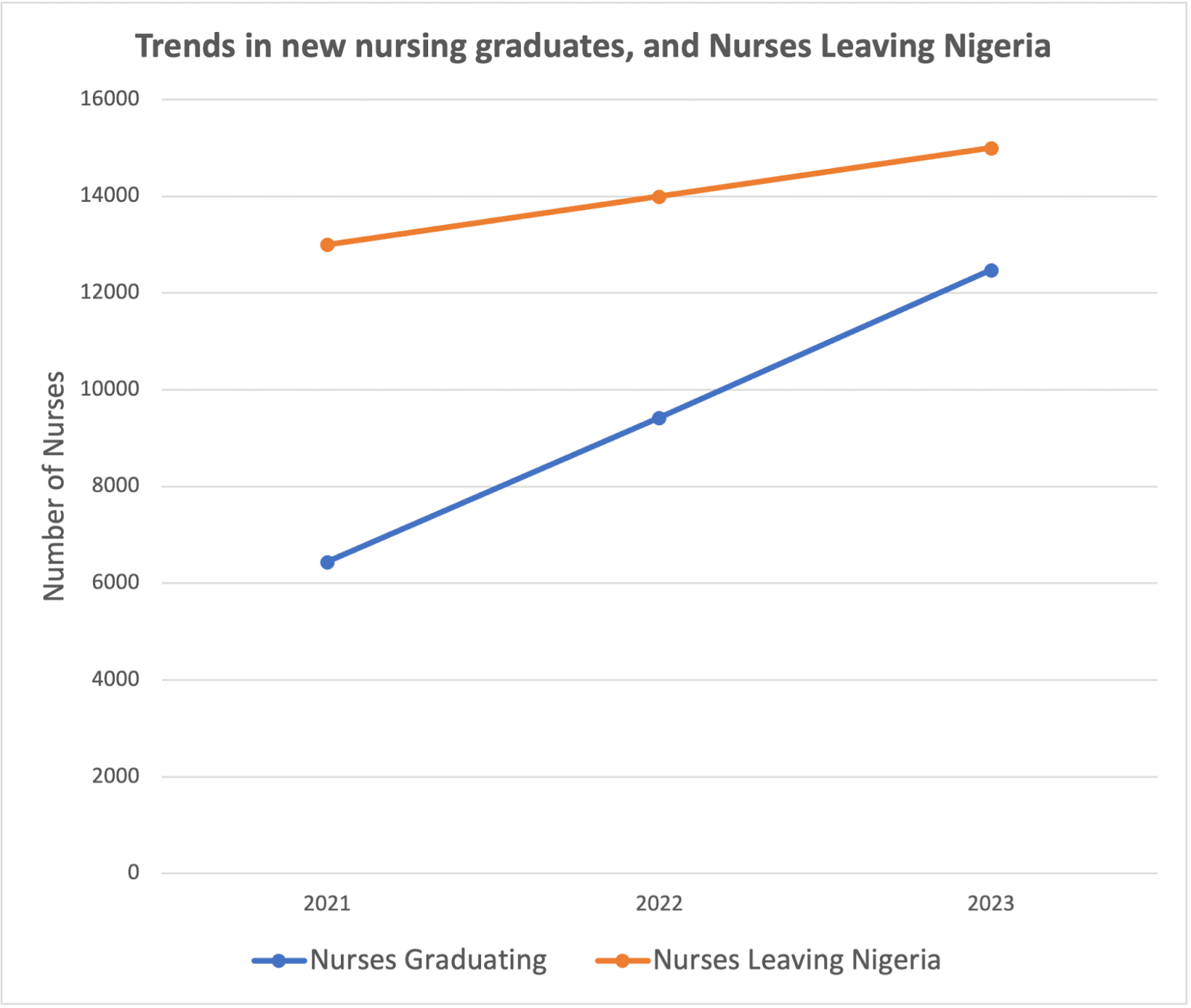

To express this situation graphically, the best graph to illustrate whether or not nurse Migration is a "Win-Win" for both Nigeria and England might have looked more like this (forgive the poor formatting!)

Over the last 3 years Nigeria has lost a net 13,500 nurses. This is a loss of about 1% of their nurse workforce a year, while Nigeria needs an increase of around 2.5% nurses yearly just to keep up with population growth. This assumes that no nurses left or joined the Nigerian workforce for other reasons. Nurses may leave the Nigerian workforce due to retirement or for other work, while nurses could also be entering Nigeria from other countries to work - I doubt these adjustments would make a big difference to the overall analysis.

Based on this data, it looks like England will win and Nigeria will lose. My main claim is that it is incorrect to claim a win-win scenario for two countries when emigration from Nigeria includes a majority of nurses leaving for many other countries – not just the UK. I’m very happy to be shown where I’ve gone wrong here and welcome any comments!

An Author's response

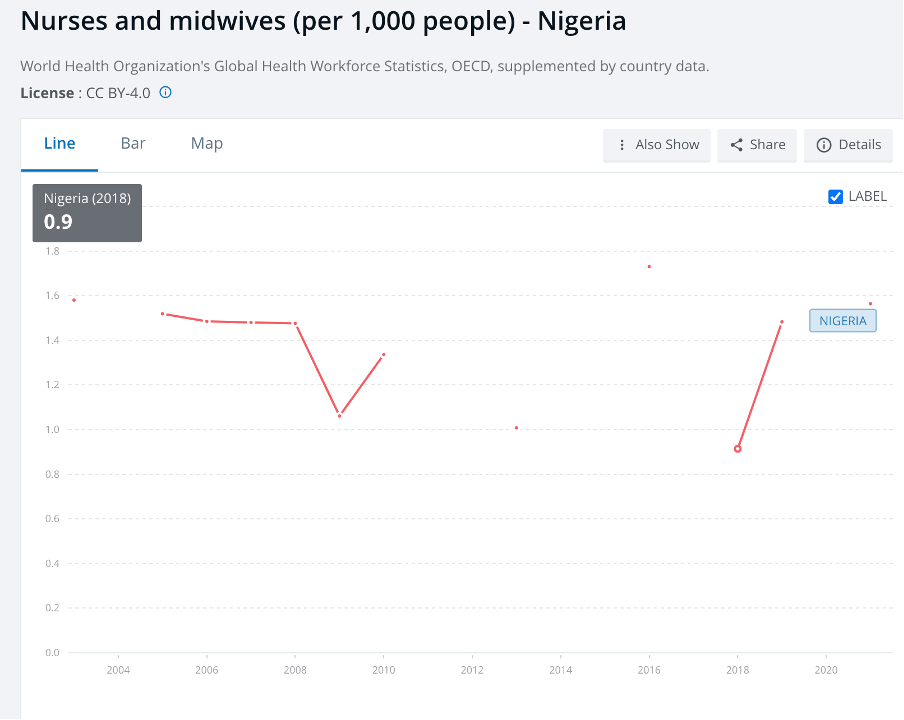

Privately, one of the authors briefly responded that their argument is based on the change in trainees and migrants over time. This still avoided my concern: you cannot look at migration outflows and inflows between two countries in a vacuum. The author also noted WHO data that shows a flat trend in the number of nurses per 1,000 people. I agree that tracking “nurses per capita” over time would be the best way to measure whether the nurse situation in Nigeria is improving or deteriorating. However the world bank data appears grossly inaccurate. Their “nurses per 1,000 population” number fluctuates implausibly between 1.75 per 1,000 in 2016, to almost half that 0.9 per 1,000 in 2018 then back up 1.5 per 1,000 the next year. Unless 100,000 nurses left Nigeria over 2 years then flooded back in the next year (not the case), the data is absurd and not to be trusted. The most proximate data we have to understand trends in nursing numbers is probably the data above - total number of nurses trained each year vs, those leaving he country (as displayed above). I don't think we have a reliable data source for nurses per capita in Nigeria.

An Implausible WHO Data Set

Also, (a side point) the authors' argument that Nigerian nursing institutions could be increasing their trainee numbers as a direct response to the UK policy doesn’t make much sense either. There would be a long lag time (3-5 years of training) before we would see any response to a new policy which took in more nurses from another country. Instead nurse training increases rapidly 1-2 years after UK immigration increases. I think you could make a decent argument that Nigeria is increasing nursing training in response to a general overall trend in nurse emigration, but not just from the UK policy.

In summary looking at trends and number of nurse emigration (what I think the article tries to do), the data appears to show net harm to the Nigerian Health System, not a “win-win” at all.

If I’m right, then I think the premise for the article is invalid – i t should probably be retracted or rewritten. I don’t love being that guy who brings the criticism and would rather have resolved this without posting here, but I think truth-seeking is important, especially when addressing Open Philanthropy funded think tanks. I also think when you chase a potential inaccuracy in good faith, it's usually best to continue until the loop is closed.

I recognize there’s more than a chance I’m wrong here, so I’m very open to being rebuffed in part or in full. I'll edit or retract the post based on convincing responses. I would especially appreciate a response from CGD authors or staff.

- ^

I don’t have a strong opinion either way on the merits of high-skilled immigration. Part of what prompted me to look into this issue more is that I had a vague idea of starting a nursing school in Uganda, in partnership with the UK (or other) government, which could supply both our organisation OneDay Health and a high income country with nurses.

- ^

Before writing this I tried multiple times to get an adequate response from the authors.

1) Contacted CGD by e-mail 3 months ago (response “your response was fed back to the authors for their consideration” only)

2) Contacted the individual authors via e-mail 1 month ago (no response)

3) Posted something similar to this on the EA Global Health and Development Slack (received a short response from one author, discussed here)

One of the authors of the original CGD blog here.

Hi Nick,

Thanks again for engaging. I don’t think your criticism is correct and I’ll try again to explain why here in more detail.

Our blog argued that after a UK visa policy change in 2020, there was a change in the trend or growth rate in both nurse migrants to the UK and new nurse trainees. To show this we present data from both before and after the policy change in 2020. The data you present from only post-2021 can't therefore refute our argument. We’re arguing that the situation could have been worse in the absence of the policy change, with even fewer new nurses being accredited in Nigeria.

Between 2018 and 2020 there was increasing migration to the UK, before the visa change, but the rate of increase dramatically accelerated following the visa change. In our previous blog we left implicit the idea of the counterfactual - that absent the policy change in 2020, trends would have continued as they had previously.

What about other countries?

You’re right to point out our lack of data for other destination countries. If our theory is correct (and it is only really a theory), we should expect to see a spike in nurse migration to the UK after 2020, and no change in nurse migration to other destination countries. The best data on this would probably be going through each destination country's records, but as a short-cut I took a look at the OECD data on annual flows of Nigerian-trained nurses to OECD countries. This data is I’m sure flawed, but it is entirely consistent with our argument. The OECD suggests that in the most recent year for which data is available the UK is by far the largest recipient of nurse migrants from Nigeria, with a flow of 1,709 in the latest available year, followed by the United States (87), Ireland (82), Canada (36), New Zealand (24), Germany (9), and Italy (1). Furthermore, the trends fit our theory entirely. Unfortunately, there is no data for the United States after 2015, but for Ireland, Canada, New Zealand, Germany, and Italy, there is no change in annual flows after 2021, whilst there is a huge spike for the UK.

Is this really plausible? It probably shouldn’t be that surprising that the largest flows from anglophone Nigeria are to other anglophone countries, with a particularly high demand for jobs in the UK given historical links and the fact that it is geographically closer to Nigeria than the other anglophone countries and in a closer time zone. For another source, a recent survey of Nigerian nurses found that the UK was the most preferred migration destination (Badru et al 2024, Investigating the emigration intention of health care workers: A cross‐sectional study).

What about the short time lag between the visa policy change and nurse training?

Is it implausible that nurse graduate numbers would increase so quickly in response to visa opportunities, given that training takes 3-5 years? This is a fair concern. If there was a steady pipeline of trainees progressing smoothly through the 3-5 year training course and all trainees then taking the professional exam at the end of their training period, then yes it would be impossible to see such a sudden increase. If however on the other hand there are significant numbers of trainees who have been enrolled on and off for a cumulative period of 3-5 years but had not previously sat the professional exam, for instance due to a lack of available job opportunities, then the emergence of new job opportunities could easily lead to the observed rapid bump in exam candidates.

Is migration reducing the availability of health care in Nigeria?

For this to be true, you would have to assume that all trained health care workers are able to find jobs in Nigeria in healthcare, which doesn’t seem likely to be true to me. You dismiss the World Health Organisation workforce data on nurses per capita because it is noisy, and argue we should instead rely on the data from the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria, a government agency. I have bad news for you, because the WHO gets its data mostly from government agencies. WHO supplements government data where it can with more reliable census or survey data, but its unlikely to be significantly less reliable than the official government data. Official data from low- and middle-income countries is often noisy, but what does seem apparent to me from the long time period available in the WHO data is that there is no ongoing downward trend in the availability of nurses in Nigeria. An alternative data source are the Demographic and Health Surveys, which show the share of births attended by a skilled provider. This is relatively flat over time from 1990 to 2021.

Ultimately our blog was speculative - we have a clear theory that training should respond to job opportunities, which seems to be consistent with the data we presented. As we wrote in the blog, this data is not definitive and doesn't prove our argument. But the data you have presented doesn’t contradict our argument either, and neither do any of the other new data sources I have consulted, whether from the OECD, WHO, or DHS. None of this data is perfect and we might be wrong, but I don’t think you’ve made that case yet.

Thanks,

Lee

Thanks yes I would agree the article might hold water if UK Nurses made up over perhaps 60 percent of emigration

Even on a sanity check there's no chance only 2000ish nurses leave Nigeria every year. It's way too low to even be plausible. I think there's a major issue here (which is common and somewhat understandable) with giving credence to sources because they are perceived to be "trustworthy' even when their numbers are obviously meaningless. The WHO and OECD data cited should be dismissed out of hand for absurdity, but I think Lee gives it credence bec... (read more)