Crosspost of my blog.

You shouldn’t eat animals in normal circumstances. That much is, in my view, quite thoroughly obvious. Animals undergo cruel, hellish conditions that we’d confidently describe as torture if they were inflicted on a human (or even a dog). No hamburger is worth that kind of cruelty. However, not all animals are the same. Contra Napoleon in Animal Farm, all animals are not equal.

Cows are big. The average person eats 2400 chickens but only 11 cows in their life. That’s mostly because chickens are so many times smaller than cows, so you can only get so many chicken sandwiches out of a single chicken. But how much worse is chicken than cow?

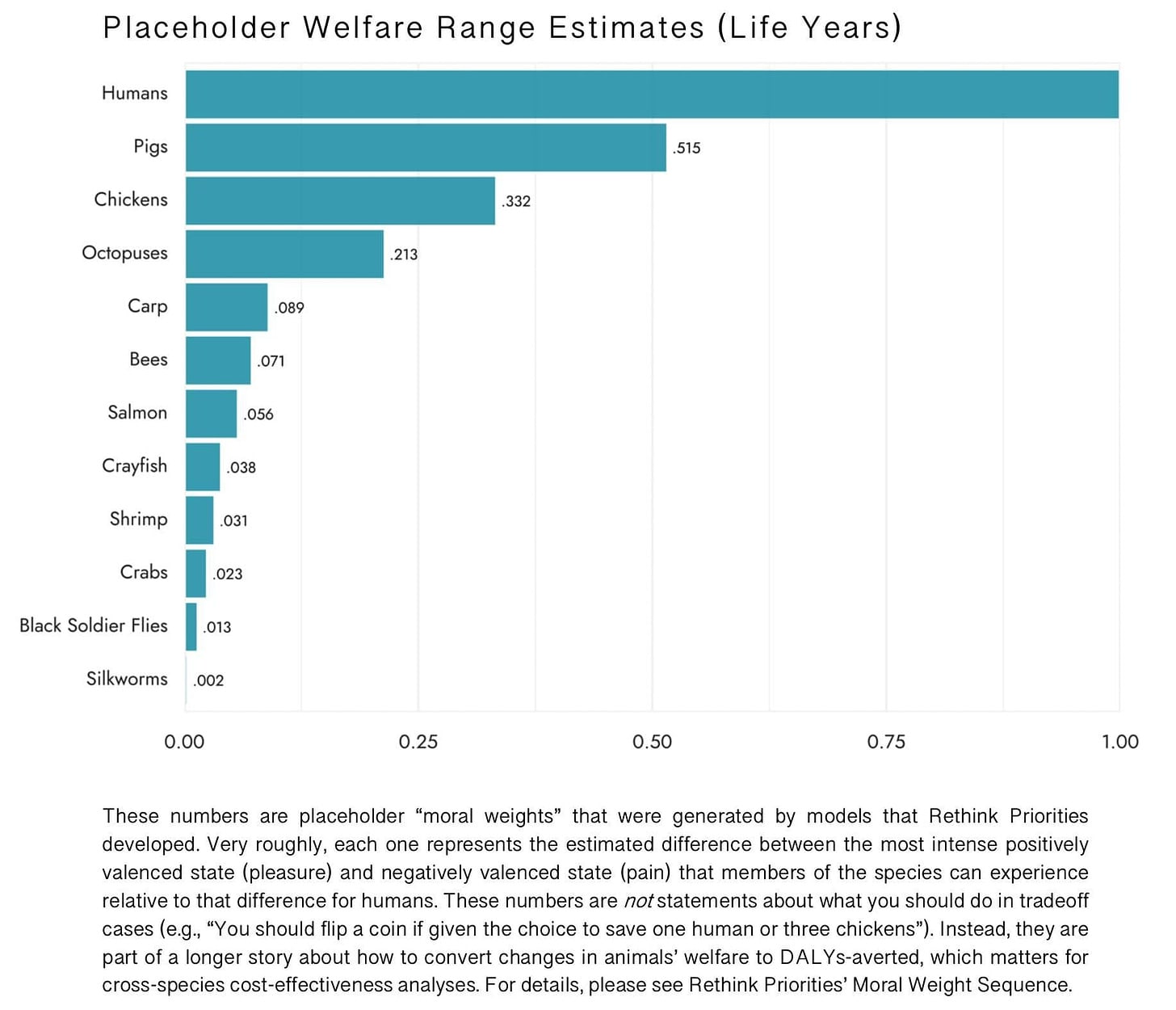

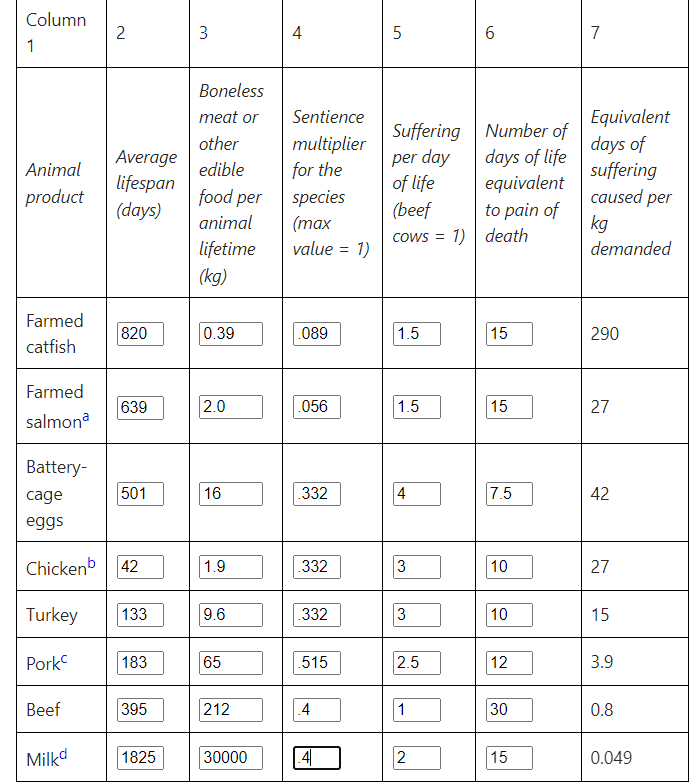

Brian Tomasik devised a helpful suffering calculator chart. It has various columns—one for how sentient you think the animals are, compared to humans, one for how long the animals lives, etc. You can change the numbers around if you want. I changed the sentience numbers to accord with the results of the most detailed report on the subject (for the animals they didn’t sample, I just compared similar animals), done by Rethink Priorities:

When I did that, I got the following:

Rather than, as the original chart did, setting cows = 1 for the sentience threshold, I set humans = 1 for it. So therefore you should think in terms of the suffering caused as roughly equivalent to the suffering caused if you locked a severely mentally enfeebled person or baby in a factory farm and tormented them for that number of days. Dairy turns out not that bad compared to the rest—a kg of dairy is only equivalent to torturing a baby for about 70 minutes in terms of suffering caused. That means if you get a gallon of milk, that’s only equivalent to confining and tormenting a baby for about 4 and a half hours. That’s positively humane compared to the rest!

Now I know people will object that human suffering is much worse than animal suffering. But this is totally unjustified. Making a human feel pain is generally worse because we feel pain more intensely, but in this case, we’re analyzing how bad a unit of pain is. If the amount of suffering is the same, it’s not clear what about animals is supposed to make their suffering so monumentally unimportant. Their feathers? Their lack of mental acuity? We controlled for that by having the comparison be a baby or a severely mentally disabled person (babies are dumb, wholly unable to do advanced mathematics). Ultimately, thinking animal pain doesn’t matter much is just unjustified speciesism, wherein one takes an obviously intrinsically morally irrelevant feature like species to determine moral worth. Just like racism and sexism, speciesism is wholly indefensible—it places moral significance on a totally morally insignificant category.

Even if you reject this, the chart should still inform your eating decisions. As long as you think animal suffering is bad, the chart is informative. Some kinds of animal products cause a lot more suffering than others—you should avoid the ones that cause more suffering.

Dairy, for instance, causes over 800 times less suffering than chicken and over 1000 times less than eggs. Drinking a gallon of milk a day for a year is then about as bad as having a chicken sandwich once every four months. Chicken is then really really bad—way worse than most other things. Dairy and beef mostly aren’t a big deal in comparison. And you can play around the numbers if you disagree with them—whatever answer you come to should be informative.

I remember seeing this chart was instrumental in my going vegan. I realized that each time I have a chicken sandwich, animals have to suffer in darkness, feces, filth, and misery for weeks on end. That’s not worth a sandwich, no matter how tasty. But if you are going to eat meat, at least lay off the chicken.

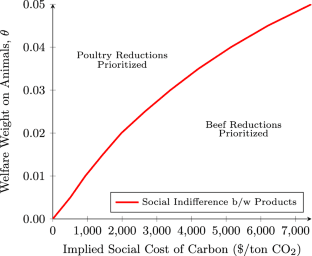

Thanks, Vasco! You are welcome to list me in the acknowledgements. I’m glad to have the reference to Tomasik’s post, which Timothy Chan also cited below, and appreciate the detailed response. That said, I doubt we should be agnostic on whether the overall effects of global heating on wild animals will be good or bad.

The main upside of global heating for animal welfare, on Tomasik’s analysis, is that it could decrease wild animal populations, and thus wild animal suffering. On balance, in his view, the destruction of forests and coral reefs is a good thing. But that relies on the assumption that most wild animal lives are worse than nothing. Tomasik and others have given some powerful reasons to think this, but there are also strong arguments on the other side. Moreover, as Clare Palmer argues, global heating might increase wild animal numbers—and even Tomasik doesn’t seem sure it would decrease them.

In contrast, the main downside, in Tomasik’s analysis, is less controversial: that global heating is going to cause a lot of suffering by destroying or changing the habitats to which wild animals are adapted. ‘An “unfavorable climate”’, notes Katie McShane, ‘is one where there isn’t enough to eat, where what kept you safe from predators and diseases in the past no longer works, where you are increasingly watching your offspring and fellow group members suffer and die, and where the scarcity of resources leads to increased conflict, destabilizing group structures and increasing violent confrontations.' Palmer isn’t so sure: ‘Even if some animals suffer and die, climate change might result in an overall net gain in pleasure, or preference satisfaction (for instance) in the context of sentient animals. This may be unlikely, but it’s not impossible.’ True. But even if it’s only unlikely that global heating’s effects will be good, it means that its effects on existing animals are bad in expectation.

There’s another factor which Tomasik mentions in passing: there is some chance that global heating could lead to the collapse of human civilisation—perhaps in conjunction with other factors. In some respects, this would be a good thing for non-humans—notably, it would put an end to factory farming. It would also preclude the possibility of our spreading wild animal suffering to other planets. On the flipside, however, it would also eliminate the possibility of our doing anything sizable to mitigate wild animal suffering on earth.

Now, while there may be more doubt about the upsides than about the downsides of our GHG emissions, that needn’t decide the issue if the upsides are big enough. But even if Tomasik and others are right that wild animal lives are bad on net, there’s also doubt about whether global heating will reduce the number of wild animal lives. And even if both are these premises are met, I’m not sure they’d outweigh the suffering global heating would inflict on those wild animals who will exist.

I think you have misinterpreted what my article about discounting is recommending. In contrast to some other writers, I’m not calling for discounting at the lowest possible rate. Even at a rate of 2%, catastrophic damages evaporate in cost-benefit analysis if they occur more than a couple of centuries hence, thus giving next to no weight to the distant future. However, a traditional justification for discounting is that if we didn’t, we’d be obliged to invest nearly all our income, since the number of future people could be so great. I argue for discounting damages to those who would be much better off than we are at conventional rates, but giving sizable—even if not equal—weight to damages that would be suffered by everyone else, regardless of how far into the future they exist. My approach thus has affinities with the one advocated by Geir Asheim here.

One implication is that while we’re under no obligation to make future rich people richer, we ought to be very worried about worst-case climate change scenarios, since in those humans could be poorer. Another is that since most non-humans for the foreseeable future will be worse off than we are, we shouldn’t discount their interests away.