This is a transcript of my opening talk at EA Global: London 2025. In my talk, I challenge the misconception that EA is populated by “cold, uncaring, spreadsheet-obsessed robots” and explain how EA principles serve as tools for putting compassion into practice, translating our feelings about the world's problems into effective action.

Key points:

- Most people involved in EA are here because of their feelings, not despite them. Many of us are driven by emotions like anger about neglected global health needs, sadness about animal suffering, or fear about AI risks. What distinguishes us as a community isn't that we don't feel; it's that we don't stop at feeling — we act. Two examples:

- When USAID cuts threatened critical health programs, GiveWell mobilized $24 million in emergency funding within weeks.

- People from the EA ecosystem spotted AI risks years ahead of the mainstream and pioneered funding for the field starting in 2015, helping transform AI safety from a fringe concern into a thriving research field.

- We don't make spreadsheets because we lack care. We make them because we care deeply. In the face of tremendous suffering, prioritization helps us take decisive, thoughtful action instead of freezing or leaving impact on the table.

- Surveys show that personal connections are the most common way that people first discover EA. When we share our own stories — explaining not just what we do but why it matters to us emotionally — we help others see that EA offers a concrete way to turn their compassion into meaningful impact.

You can also watch my full talk on YouTube.

One year ago, I stood on this stage as the new CEO of the Centre for Effective Altruism to talk about the journey effective altruism is on. Among other key messages, my talk made this point: if we want to get to where we want to go, we need to be better at telling our own stories rather than leaving that to critics and commentators. Since then, we’ve seen many signs of progress, especially in recent months.

In May, TIME magazine featured EA not just once, but twice in its “Philanthropy 100,” celebrating Peter Singer’s influence, as well as Cari Tuna and Dustin Moskovitz’s use of EA frameworks in their philanthropic giving through Open Philanthropy.

I have also been glad to see EA in the news at the New York Times, where they turned to us for input on topics ranging from donations in response to USAID cuts to the potential implications of digital sentience.

But maybe the most surprising — and, let’s be honest, definitely the most entertaining — recent coverage came from the late night Daily Show. Many of you will have already seen it, but for those of you who haven’t, here’s the video.

There’s a lot to love here. Shrimp welfare getting a primetime platform, and a comedy show making space to portray the horror of inhumane slaughter methods, overcrowding, and eyestalk ablation. It’s playful and funny, showing that treating our work as deadly serious doesn’t mean we have to take ourselves too seriously. It’s a segment I hope many more people see.

But through the laughter, there’s a line that sticks out: “Fuck. Your. Feelings.”

Not the most polite message to use to kick off EAG, but one worth talking about. This caricature — that EA is populated by cold, uncaring, spreadsheet-obsessed robots — would be easy to laugh off if it was a one-off, but it isn’t. This misconception follows us around, in many contexts, in polite and impolite forms…despite the fact that it’s importantly wrong.

It’s a mischaracterization that doesn't represent who we are, but has important implications nonetheless. It affects how we relate to our work, how we tell stories about our movement, and how well we are able to inspire other people to join our efforts to make the world a better place.

But most of us aren’t here without feelings or despite our feelings. In many cases, we’re here because of them.

Part of why I think this caricature doesn’t reflect EA as a whole is because I know that it doesn’t describe me. When I think of why I want to do good, I end up thinking a lot about the feelings I have. And when I think about how feelings can motivate action, I come back to a cause that hasn’t historically received lots of airtime at EA Global: potholes.

Now, given this is EAG, you might think I’m talking about potholes in LMICs and their counterfactual impact on traffic fatalities. But, no. I actually want to talk about potholes in my hometown of Omaha, Nebraska.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with Nebraska, it’s a landlocked state in the middle of the US, and when I once told a European that it’s where I’m from, he remarked, “Ooh! I know Nebraska! Famously the most boring place in America!”

It's also where my father became famous for filling potholes.

My father had a day job, and being a vigilante construction worker was not it. He ran a small online travel agency from our home in Omaha, where the city had neglected its decaying infrastructure for years. Every day, my dad and everyone else in the city were stuck driving over crumbling roads to work, or to the grocery store, or to drop kids like me off at school. And many of them felt mad about it.

And one day, when my father drove over one pothole too many, he got mad too. But unlike everyone else, he didn't just get mad. He decided he would fill the potholes himself.

So he went out, bought his own asphalt patching material, and went around the neighborhood filling in the holes. He spent countless hours and thousands of dollars just to make the roads a little less broken.

Now, I have no desire to advocate for potholes as one of the world’s most pressing

problems. But I want to point out what unites a person who feels angry about potholes that their local government doesn’t fill, a person who feels dismayed by gaps in global aid, a person who feels sad that animals are tortured en masse to feed us, and a person who feels fearful about the possibility of human extinction from transformative technology.

All of these people have something important in common when they say: This is a problem I care about, feel strongly about, and I want to take action.

A sad fact about the world is that potholes aren’t the only problem that people encounter and choose to do nothing about.

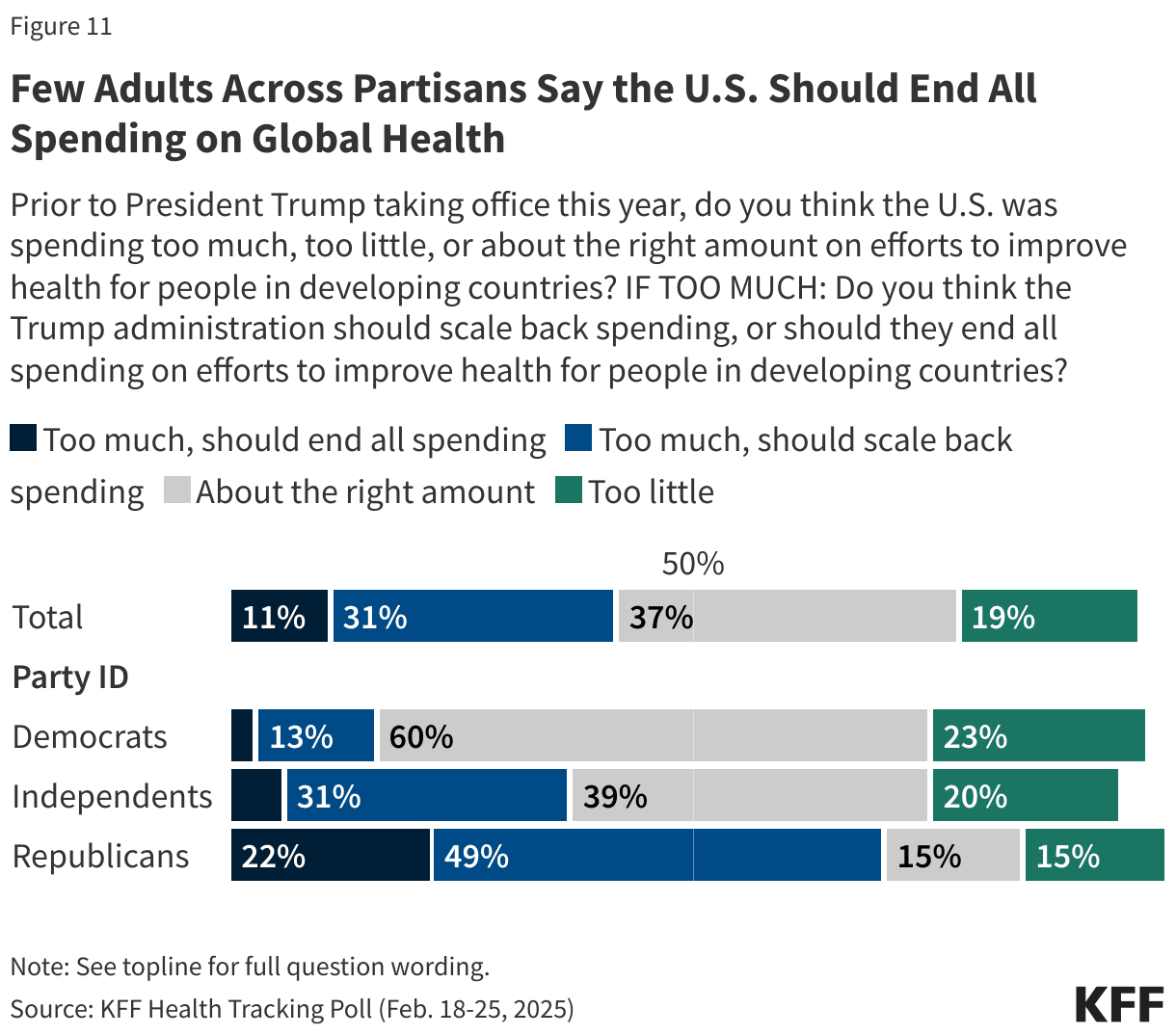

Take the recent cuts to USAID. The majority of Americans support maintaining or increasing the amount of American aid that existed prior to Trump taking office, which suggests that there are at least 150 million Americans displeased with the administration’s recent decisions. Yet only a fraction have taken action.

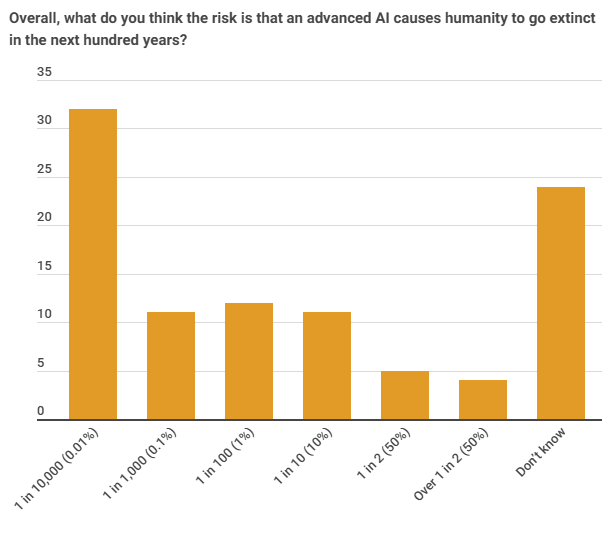

Take AI risk. On this side of the pond, about a quarter of Brits report believing there’s at least a 10% chance AI causes human extinction within the next century, which makes for about 15 million adults feeling some degree of fear for the fate of humanity. Yet again, only a fraction have taken action.

There are many people who feel something is wrong and choose to look away.

When forced to drive over potholes day after day, it can feel better to turn off the part of our brains that tells us something is wrong than to sit with our building anger or sadness or fear and confront the reality that the problem has gotten really bad, and nobody is coming to fix it.

But we know that tuning out isn’t the only option.

There’s a fraction of the world that doesn’t just keep driving! There are people who look at holes much bigger than potholes and say: If no one else will fix this, I will. And a startlingly large proportion of those people are in this room[1] right now.

Many of us in the EA community have dedicated ourselves to staying with our feelings

and not looking away. We stare at eye-watering problems day after day. What distinguishes this community isn’t that we don’t feel. It’s that we don’t stop at feeling. We act.

Effective altruism provides tools for us to translate our feelings into action.

When the new US administration issued stop-work orders that froze USAID's global health programs, GiveWell didn’t wait in vain for someone else to step in. They moved quickly to plug the most critical gaps. Within weeks, they mobilized $24 million in emergency funding to provide life-saving malaria prevention and HIV testing services. They're currently investigating more than $100 million in additional grants as they continue to manage the fallout from these cuts.

When it comes to AI safety, the effective altruism community was one of the earliest groups taking action. Open Philanthropy identified “risks from artificial intelligence” as a top priority cause way back in 2015. Since then, our community has grown AI safety from a niche concern into a thriving field with its own institutions, training programs, and research agendas. Programs like MATS — Machine Learning Alignment and Theory Scholars — have trained a new generation of AI safety researchers pioneering novel research agendas like externalized reasoning oversight, situational awareness evaluations, and gradient routing — which all sound extremely important and which I will confidently pretend to understand if you ask me about them.

From conversations with many of you, and with others across our community, it’s clear that these actions were preceded by strong feelings. Sadness. Anger. Hope.

This is what compassionate action looks like: translating our feelings into concrete steps that help. EA gives us the tools to do that. Not to feel less, but to act more.

Why is it, then, that sometimes we’re portrayed as walking, talking spreadsheet robots?

Part of it, I think, is that when our stories are being told, by us or by others, the focus tends to be on what we’re doing or not doing. It’s our actions that count, after all. In comparison, it can be difficult to make space for the how and the why. It’s not newsworthy that someone felt upset by a pothole. It is newsworthy what someone did in response to it.

In EA, our ‘whats’ tend to attract attention — shrimp welfare and digital sentience are counterintuitive and controversial, which makes them good for clicks. Whereas our ‘whys’ — our feelings — are more intuitive, more widely shared, and more recognizably human. In other words, they seem boring.

But that doesn’t mean we should cut them from our story.

There’s a long track record of people involved in EA naming feelings as our foundations. Back in 2017, Holden Karnofsky wrote about radical empathy as a motivating reason to care about animals and people on the other side of the planet, in the same way it was once radical to recognize the moral worth of a neighbour of a different race.

In his book The Precipice, Toby Ord talks about why he cares about humanity’s future:

Indeed, when I think of the unbroken chain of generations leading to our time and of everything they have built for us, I am humbled. I am overwhelmed with gratitude; shocked by the enormity of the inheritance and at the impossibility of returning even the smallest fraction of the favor. Because a hundred billion of the people to whom I owe everything are gone forever, and because what they created is so much larger than my life, than my entire generation.

But these motivating feelings rarely make it into stories about our work. It’s too easy to focus on what’s different. And the thing that separates the majority of the people inside this room from the majority of people outside of it is our actions, not our feelings.

Even when it’s not newsworthy, it can be worth reminding people that, hey, like just about everybody else, we’d find it really sad if we all died.

Sometimes, it’s ok to tell people what they already know and feel. Sometimes, it’s ok not to tell people about all of the ways they could be acting differently, and instead, validate all of the ways their feelings make sense. Sometimes, it’s okay to not emphasize what’s original and unique about EA, but rather the ways in which we’re exactly the same as everyone else.

The lack of attention on what makes us the same can intensify focus on what makes us different. And that means that oftentimes, discussions surrounding EA center less on what we do and more on what we don’t do.

You aren’t focused on homelessness in your own backyard. You aren’t trying to fix your country’s broken healthcare. You aren’t focused on the discrimination you see day in and day out. And because there’s so much concern with what we aren’t doing, that can lead people to believe we don’t care.

I don’t think that’s true, though. I’m sad every time I see someone living and suffering on the streets where I live in San Francisco. I’m filled with love for my parents and feel afraid when I think of their health declining. I’m angry and upset about the racism and homophobia that I witnessed growing up in Nebraska.

But I also feel angry at a food system that plucks the eyestalks of shrimp, at governments that leave children to die of malaria, and at corporations that recklessly race to develop technologies that could endanger us all.

I care about every tortured animal, every dying child, and every future individual that could have a fulfilling life. But I can’t help them all. And if we don’t want to deny the world’s problems, and if we don’t want to disassociate from them, then we need a way to decide which feelings to act on, and which actions to take.

That is compassion. Compassion is what we call converting our feelings into actions that help others. It is the bridge between our awareness that other people are hurting and our actions to make it better.

Effective altruism is compassionate. This community is compassionate. We recognize that the world doesn’t need us to take on its suffering; it needs us to take action to alleviate its suffering.

Taking ideas seriously is a common trait among the EA community. I think there’s a related EA trait: taking feelings seriously.

When we feel sad or angry or afraid about the state of the world, we ask ourselves: What can we do about it, with the resources available to us? What can I do about it, with the time and money available to me?

EA principles are still the best tools I know of to answer these questions, which is to say they’re the best tools I know of to put compassion into practice. Our feelings tell us that action is required, but in the face of so many complex and seemingly insurmountable problems, our feelings alone can’t tell us what action to take, or which problem to prioritize.

That’s where our principles come in.

Impartiality, scope sensitivity, truthseeking, and tradeoffs may seem cold or uncaring at first glance, but they’re not the problem — they’re an essential part of the solution.

Without impartiality, we’d be blind to the needs of those far away or unfamiliar.

Organizations like Rethink Priorities have done pioneering work on sentience and how to weigh animal suffering, extending our moral circle.

Without scope sensitivity, we’d fail to help as many as we can by as much as we could. Scope sensitive members of the community haven’t flinched while going down the species by body size and up the species by population size, from cows to chickens to shrimp to insects, ultimately improving the lives of billions of animals.

Without truthseeking, we’d be beholden to familiar ideas even when they lead us astray. This community has funded and used research from the Welfare Footprint Institute to change their strategies and better understand how to help chickens, fish, and pigs.

Whether we like it or not, everyone who wants to make a difference has to make hard tradeoffs. Recognizing tradeoffs isn’t a failure of compassion. It is an expression of it. Our resources are finite, and much smaller than the full scale of all the problems and promise in our world. So we have to choose.

Between just the US and UK, there are about two million registered non-profits, over 100 times the number of McDonald's. Meaning every time we dedicate our resources to one charity, we’re choosing not to dedicate them to millions of others.

One way to choose is to stick to what we know, what’s close to our heart or close to home.

The other way is to make spreadsheets. We know it’s unconventional (and for many it’s counterintuitive) to express deep care by doing a cost-effectiveness calculation. It’s understandable that, without knowing why we do this, people might watch us intentionally and calculatedly choosing not to help those close to home, and assume that we are cold and uncaring.

But I think that gets EA the wrong way round. We don’t make spreadsheets because we don’t care. We make spreadsheets because we care so much.

Why does this misconception matter?

If compassionate people don’t see us as compassionate, and they don’t hear us communicating that EA is a meaningful way to be compassionate, we risk alienating like-minded people who might otherwise dedicate their resources to tackling the world’s most pressing problems. In every survey Rethink Priorities has run on how people first find out about EA, personal contacts come out on top.

How we show up matters. It mattered to me in my EA journey.

When I first discovered EA, I was deeply skeptical of AI safety. It took me a long time to be convinced that it was something I should be concerned about. And the primary reason it took so long wasn’t that I was presented with bad arguments, and it wasn’t because I was stupid. It was because I associated AI safety with cold and faceless people on the internet, so I didn’t warm up to them or their ideas.

Now, this was not my most truthseeking reaction. But it was a human one. The people I mentally associated with AI didn’t seem particularly compassionate to me. Instead, they seemed self-centered: inflating the importance of their work and ignoring very real diseases killing very real people on the other side of the world because the only thing that could threaten them and other wealthy Westerners was a sci-fi fantasy.

But what eventually changed my mind was spending time with them. Because only then did I learn not just about their ideas, but also about their feelings. And importantly, I learned not just about the very real terror they felt about the potential for all humanity to die, but also the compassion they demonstrated for the suffering and the poor, as people who were vegans, kidney donors and 10% pledgers.

These people clearly felt strongly about the suffering of others and sincerely believed the best way they could help others was by shaping the development of transformative technology. Once I understood that we had common motivations, I heard their arguments differently.

And while specific diets or donations are not and should not be barriers to entry to participate in this community, I think the people in this room are here because we care. I want to make it easier for others to see that caring.

However you feel, there’s power in showing up as your full, feeling self. Our stories should convey both sides of our compassion — both the strength of our feelings and the impact of our actions. Those feelings and actions will vary from person to person, from org to org, and from story to story, which gives each of us the opportunity to reach different audiences with different emotional registers.

The EA brand won’t be controlled or contained by any one EA organization, CEA or otherwise. Ultimately, it will be a composite function of every EA actor and every EA ambassador and advocate, which is to say that it will be a composite of all of you. It will be a function of the stories told about you, and the stories you tell yourselves. We are more than our spreadsheets. The diversity of our stories can strengthen our outreach if we make EA’s public persona more reflective of the humans who built it.

So, with that in mind, I’m going to ask that you don’t fuck your feelings. Because sometimes, in order to make people think differently and act differently, we first need to make them feel.

So, I hope you spend time learning, but I also hope you spend time feeling. You are surrounded by so many compassionate people who feel the holes in the road and take heroic action to fill them in for others. I want to continue building this community because I believe in our compassion and because I believe in our principles. I feel inspired to advocate for EA because I believe we’ve already achieved so much and because I believe we’re only just getting started.

- ^

Or reading this post!

Really appreciated this talk. It did a great job of holding both feeling and strategy — not shying away from anger, sadness, or hope, but also not getting stuck there. The story about your dad filling potholes really stayed with me — such a simple, clear example of what it means to notice harm and just decide to help. I think sometimes we act like caring and action need to be either emotional or analytical, but this reminded me that they can (and should) be both. Spreadsheets and systems can be powerful tools because we care — not instead of it. Thanks for naming that so clearly!