Bostrom's Maxipok principle suggests reducing existential risk should be the overwhelming focus for those looking to improve humanity’s long-term prospects. This rests on an implicitly dichotomous view of future value, where most outcomes are either near-worthless or near-best.

We argue against the dichotomous view, and against Maxipok. In the coming century, values, institutions, and power distributions could become locked-in. But we could influence what gets locked-in, and when and whether it happens at all—so it is possible to substantially improve the long-term future by channels other than reducing existential risk.

And this is a fairly big deal: both because Maxipok could mean leaving value on the table, and in some cases because following Maxipok could actually do harm.

This is a summary of “Beyond Existential Risk”, by Will MacAskill and Guive Assadi. The full version is available on our website.

Defining Maxipok

Picture a future where some worry that terrorist groups could use advanced bioweapons to wipe out humanity. The world's governments could coalesce into a strong world government that would reduce the extinction risk from 1% to 0%, or maintain the status quo. But the world government would lock in authoritarian control and undermine hopes for political diversity, decreasing the value of all future civilisation by, say, 5%.

If we totally prioritised existential risk reduction, then we should support the strong world government. But we'd be saving the world in a way that makes it worse.

A popular view among longtermists is that trying to improve the long-term future amounts to trying to reduce existential risk. The clearest expression of this is Nick Bostrom’s Maxipok principle:

Maxipok: When pursuing the impartial good, one should seek to maximise the probability of an “OK outcome,” where an OK outcome is any outcome that avoids existential catastrophe.

Existential risk is not only the risk of extinction: it is more generally the risk of a “drastic” curtailment of humanity’s potential: a catastrophe which makes the future roughly as bad as human extinction.

Is future value all-or-nothing?

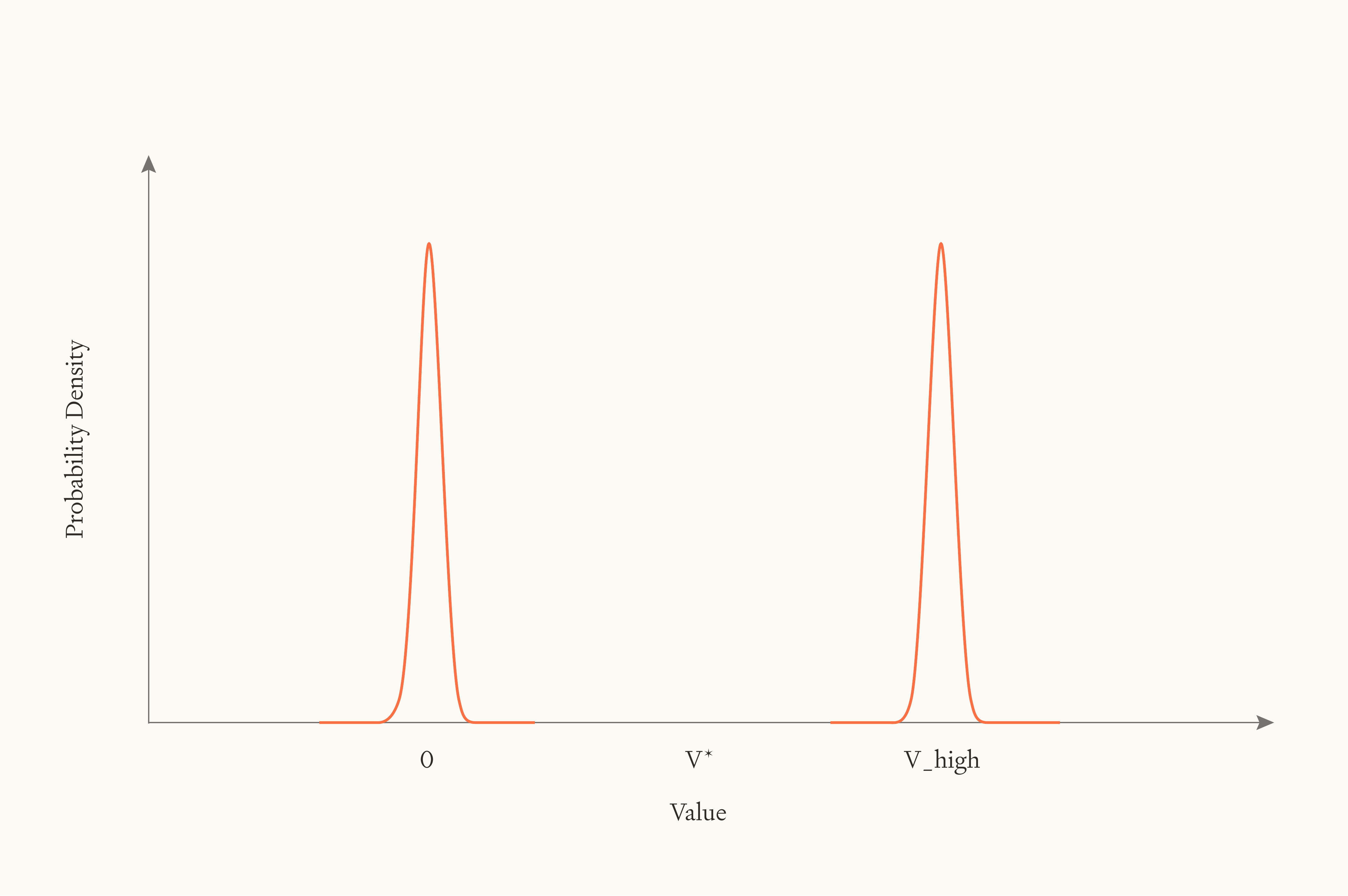

Why would this be true? We suggest it’s because of an implicit assumption, which we’ll call Dichotomy. Roughly, Dichotomy says that futures cluster sharply into two categories—either very good ones (where humanity survives and flourishes) or very bad ones (existential catastrophes). If futures really are dichotomous in this way, then the only thing that matters is shifting probability mass from the bad cluster to the good cluster. Reducing existential risk would indeed be the overwhelming priority.

Here’s a more precise definition:

Dichotomy: The distribution of the difference that human-originating intelligent life makes to the value of the universe over possible futures is very strongly bimodal, no matter what actions we take.

The case for Dichotomy

Maxipok, then, significantly hinges on Dichotomy. And it’s not a crazy view—we see three arguments in its favour.

The first argument appeals to a wide “basin of attraction” pointing towards near-best futures. Just as an object captured by a planet's gravity inevitably gets pulled into orbit or crashes into the planet itself, perhaps any society that is competent or good enough to survive naturally gravitates toward the best possible arrangement.

But there are plausible futures where humanity survives, but doesn’t morally converge. Just imagine all power ends up consolidated in the hands of a single immortal dictator (say, an uploaded human or an AI). There's no reason to think this dictator will inevitably discover and care about what's morally valuable: they might learn what's good and simply not care, or they might deliberately avoid exposing themselves to good moral arguments. As far as we can tell, nothing about being powerful and long-lived guarantees moral enlightenment or motivation. More generally, it seems implausible that evolutionary or other pressures would be so overwhelming as to make inevitable a single, supremely valuable destination.

The second argument for Dichotomy is if near-best futures are easy to achieve; perhaps value is bounded above, at a low bound, so that as long as future civilisation doesn’t soon go extinct, and doesn’t go a direction that’s completely valueless, it will end up producing close to the best outcome possible.

But bounded value doesn't clearly support Dichotomy. First, there's a nasty asymmetry: while goodness might be bounded above, badness almost certainly isn't bounded below (intuitively we can always add more awful things, and make the world worse overall). But that asymmetry wouldn’t support Dichotomy; it would support a distribution with a long negative tail, where preventing extinction could generally make the future worse. That’s not the only issue with bounded views, but at any rate they’re unlikely to make Dichotomy true.

Here's a third argument that doesn't require convergence or bounded value. Perhaps the most efficient uses of resources produce vastly more value—orders of magnitude more—than almost anything else. Call the hypothetical best use "valorium" (whatever substrate most efficiently generates moral value per joule of energy). Then either future civilisation optimises for valorium or it doesn't. If it does, the future is enormously good. If it doesn't, the future has comparatively negligible value.

There's some evidence for this heavy-tailed view of value. Philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote of love: "it brings ecstasy—ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy." One survey found that over 50% of people report their most intense experience being at least twice as intense as their second-most intense, with many reporting much higher ratios.

On the other hand, Weber-Fechner laws in psychophysics suggest that perceived intensity follows a logarithmic relationship to stimulus intensity, implying light rather than heavy tails.

But it’s hard to know how to extrapolate from human examples to learn things about the distribution of value on a cosmic scale. This Extremity of the Best hypothesis isn’t obviously wrong, but we wouldn’t bet on it.

The case against Dichotomy

Even if one of these arguments had merit, two more general considerations count strongly against it, such that we end up rejecting Dichotomy.

In the future, resources will likely be divided among different groups—different nations, ideologies, value systems, or even different star systems controlled by different factions. If space is defence-dominant (meaning a group holding a star system can defend it against aggressors, plausibly true given vast interstellar distances), then the initial allocation of cosmic resources could persist indefinitely.

This breaks Dichotomy even if the best uses of resources are extremely heavy-tailed. Some groups might optimise for those best uses, while others don't. The overall value of the future scales continuously with what fraction of resources go to which groups, and there's no reason to expect only extreme divisions. The same applies within groups. Individuals might divide their resource budgets between optimal and very suboptimal uses, but the division itself can vary widely.

Perhaps the deepest problem for Dichotomy is that we should just be widely uncertain about all these theoretical questions. We don’t know whether societies converge, whether value is bounded, whether the best uses of resources are orders of magnitude better. And when you're uncertain across many different probability distributions—some dichotomous, some not—the expected distribution is non-dichotomous. It's like averaging a bimodal distribution with a normal distribution: you get something in between, with probability mass spread across the middle range.

Non-existential interventions can persist

There's one more objection to consider. Maybe we're wrong about Dichotomy, but Maxipok is still right for a different reason: only existential catastrophes have lasting effects on the long-term future. Everything else—even seemingly momentous events like world wars, cultural revolutions, or global dictatorships—will eventually wash out in the fullness of time. Call this persistence skepticism.

We think you should reject persistence skepticism. We think it's reasonably likely—at least as likely as extinction—that the coming century will see lock-in—events where certain values, institutions, or power distributions become effectively permanent—or other forms of persistent path-dependence.

Two mechanisms make this plausible:

AGI-enforced institutions. Once we develop artificial general intelligence, it becomes possible to create and enforce perpetually binding constitutions, laws, or governance structures. Unlike humans, digital agents can make exact copies of themselves, store backups across multiple locations, and reload original versions to verify goal stability. A superintelligent system tasked with enforcing some constitution could maintain that system across astronomical timescales. And once such a system is established, changing it might be impossible—the enforcer itself might prevent modifications.

Space settlement and defence dominance. Once space settlement becomes feasible—perhaps soon after AGI—cosmic resources will likely be divided among different groups. Moreover, star systems may be defence-dominant. This means the initial allocation of star systems could persist indefinitely, with each group's values locked into their territory, other than through trade.

Crucially, even though AGI and space settlement provide the ultimate lock-in mechanisms, earlier moments could significantly affect how those lock-ins go. A dictator securing power for just 10 years might use that time to develop means to retain power for 20 more years, then reach AGI within that window—thereby indefinitely entrenching what would otherwise have been temporary dominance.

This suggests quite a few early choices could have persisting impact:

- The specific values programmed into early transformative AI systems

- The design of the first global governing institutions

- Early legal and moral frameworks established for digital beings

- The principles governing allocation of extraterrestrial resources

- Whether powerful countries remain democratic during the intelligence explosion

Actions in these areas might sometimes prevent existential catastrophes, but they often involve improving the future in non-drastic ways; contra Maxipok.

So what?

We think it’s a reasonably big deal for longtermists if Maxipok is false.

The update is something like this: rather than focusing solely on existential catastrophe, longtermists should tackle the broader category of grand challenges: events whose surrounding decisions could alter the expected value of Earth-originating life by at least one part in a thousand (0.1%).

Concretely, new priorities could include:

- Deliberately postponing or accelerating irreversible decisions to change how those decisions get made. This could mean pushing for international agreements on AI development timelines, implementing reauthorisation clauses for major treaties, or preventing premature allocation of space resources.

- Ensuring that when lock-ins occur, the outcomes are as beneficial as possible. This might involve advocating for distributed power in AI governance (rather than single-country or single-company control), encouraging widespread moral reflection before lock-ins occur, or working to ensure humble and morally-motivated actors design locked-in institutions rather than ideologues or potential dictators.

- Influencing which values and which groups control resources when critical decisions get made. This could mean promoting better moral worldviews, working on the treatment and rights of digital beings before those rights get locked in, or affecting the balance of power between democratic and authoritarian systems.

- Building better mechanisms for global coordination, moral deliberation, and governance handoffs to transformative AI systems.

None of these interventions is primarily about reducing the probability of existential catastrophe. But if Maxipok is false, they could be just as important—or even more important—than traditional existential risk reduction interventions, like preventing all-out AI takeover, or extinction-level biological catastrophes.

None of this makes existential risk reduction less valuable in absolute terms. We’re making the case for going beyond a singular focus on existential risk, to improving the future conditional on existential survival, too. The stakes remain astronomical.

This was a summary of “Beyond Existential Risk”, by Will MacAskill and Guive Assadi. The full version is available on our website.

(Having just read the forum summary so far) I think there's a bunch of good exploration of arguments here, but I'm a bit uncomfortable with the framing. You talk about "if Maxipok is false", but this seems to me like a type error. Maxipok, as I understand it, is a heuristic: it's never going to give the right answer 100% of the time, and the right lens for evaluating it is how often it gives good answers, especially compared to other heuristics the relevant actors might reasonably have adopted.

Quoting from the Bostrom article you link:

It seems to me like when you talk about maxipok being false, you are really positing something like:

Whereas maxipok is a heuristic (which can't have truth values), strong maxipok (as I'm defining it here) is a normative claim, and can have truth values. I take it that this is what you are mostly arguing against -- but I'd be interested in your takes; maybe it's something subtly different.

I do think that this isn't a totally unreasonable move on your part. I think Bostrom writes in some ways in support of strong maxipok, and sometimes others have invoked it as though in the strong form. But I care about our collectively being able to have conversations about the heuristic, which is one that I think may have a good amount of value even if strong maxipok is false, and I worry that in conflating them you make it harder for people to hold or talk about those distinctions.

(FWIW I've also previously argued against strong maxipok, even while roughly accepting Dichotomy, on the basis that other heuristics may be more effective.)

On Dichotomy:

Looking at the full article:

Thanks for putting this out!

I agree with quite a lot of this, however I think one of the most important points for whether or not we get something close to a near-best future is whether or not we have some kind of relatively comprehensive process for determining what humanity does with our future; what I’ve been calling “deep reflection,” which could be something like a long reflection or coherent extrapolated volition.

I think if such a process is used to determine how to use at least some percentage of future resources, then at least that percentage could be close to optimal value; if for some reason there is not a comprehensive process that determines any significant percentage of future resources, then I am quite pessimistic that we would get very far above 0% possible value, as getting high value seems quite difficult because it seems like there are many factors or crucial considerations (e.g. here and here) which could decrease future value, and like getting even a few of these factors wrong may mean we get close to zero value.

I am also quite sympathetic to extremity of the best. My intuition is that it is very likely that optimal use of resources is far, far better than most other likely uses. Would be happy to expand more on this if there is interest.

That said, I think it’s important to recognize the importance of such a comprehensive process as an essential unifying strategic element; conditional on avoiding any existential catastrophes, it seems to me the vast majority of future value[1] will be determined by two factors:

I think all of the other factors you mentioned are quite important, but I believe that they gain the vast majority of their value through how they influence the above two factors. Again, this is simply because (i) I believe we need such a process to determine how to get much above zero value with any degree of confidence, and (ii) it seems quite possible there will not be widespread agreement that we should use resources optimally according to the outcome of this process, but hopefully some grand bargain/existential compromise can be reached, or more optimistically perhaps we could try to get on a path where more convergence happens.

Would be curious to hear if you disagree with the previous paragraph, it feels like a pretty big crux for me.

Rather than "the vast majority of future value," perhaps it would be slightly more accurate to say "the vast majority of positive impact we will have in expectation"; perhaps we are already predestined to achieve very high value or very low value, or more importantly, perhaps there are things we could do that seem like they will have a large impact (positive or negative); but unless our actions are leading to comprehensive strategic clarity (comprehensive reflection), and the likelihood of acting on this clarity (deep reflection), if seems hard to be confident ex ante our actions are highly likely to have highly positive impact in the final analysis.

I think the big challenge here is going to be that Maxipok is easier to coordinate around because it doesn't (seem) to involve commitment to a particular future. The US and China and Russia might agree to not do things that will end the world, but it's going to be much harder to get on the same page about any decisions that cause lock-in of particular values or even a particular decision-making procedure.

As a result, getting away from Maxipok takes us more and more into pivotal-acts territory.

Very glad to see this discussed direclty, though. I would love to see at least US decision makers thinking about what a proto-viatopia looks like in the near term.

Executive summary: The authors argue that Nick Bostrom’s Maxipok principle rests on an implausible dichotomous view of future value, and that because non-existential actions can persistently shape values, institutions, and power, improving the long-term future cannot be reduced to existential risk reduction alone.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Great post, my comments are responding to the longer linked document.

1. I had a thought about quasilinear utilities and moral preferences. There, you say "What’s more, even if, given massive increases in wealth, people switch to using most resources on satisfying moral preferences rather than self-interested preferences, there is no guarantee that those moral preferences are for what is in fact good. They could be misguided about what is in fact good, or have ideological preferences that are stronger than their preferences for what is in fact good; their approximately linear preferences could result in building endless temples to their favoured god, rather than promoting the good."

Still, I think there's an argument that can be run that outcomes caused by moral preferences tend to converge / be very similar to one another. Here, the first step is to

distinguish de dicto and de re moral preferences. Second, if we imagine a group of agents with de dicto moral preferences, one argument for convergence is that each agent will be uncertain about what outcomes are morally best, and then agreement theorems suggest that once the various agents pool their information, they will tend to converge in their credence distribution over moral theories. But this means that their distribution over what outcomes are morally best will tend to converge. Connecting back to the main question, the point is that if we think that in the future most outcomes involve decision-makers being de dicto ethical, then we might expect concentration in the outcomes, if decision-makers tend to converge in their de dicto ethical credence distributions. Regardless of what is actually good, we should expect most outcomes in which agents want to be de dicto ethical to be similar, if these agents have similar credences across outcomes about the good. This only works for de dicto not de re moral preferences: if I want to help chickens and you want to help cows, no amount of pooling our information will lead to convergence in our preferences, because descriptive information won't resolve our dispute.

2. I was a bit confused about the division of resources argument. I was thinking that if the division of resources is strong enough, that actually would support dichotomy, because then most futures are quite similar in total utility, because differences across territories will tend to be smoothed out. So the most important thing will just be to avoid extinction before the point of division (which might be the point at which serious space colonisation happens). Again, after the point of division lots of different territories will have lots of different outcomes, so that the total value will be a function of the average value across territories, and the average will be smooth and hard to influence. I think maybe where I'm getting confused is you're imagining a division into a fairly small number of groups, the valorium-optimisers and the non-optimisers. By contrast, I'm imagining a division into vast numbers of different groups. So I think I agree that in your small-division case, dichotomy is less plausible, and pushing towards valorium-optimisation might be better than mitigating x-risk.

3. "if moral realism is false, then, morally, things in general are much lower-stakes — at least at the level of how we should use cosmic-scale resources" I think this argument is very suspicious. It fails according to quasi-realists, for example, who will reject counterfactual like "if moralism is false, then all actions are permissible." Rather, if one has the appropriate pro-attitudes towards helping the poor, quasi-realists will go in for strong counterfactuals like "I should have helped the poor even if I had had different pro-attitudes". Similarly, moral relativists don't have to be subjectivists, where subjectivists can be defined as those who accept the opposite counterfactuals: if I had had pro-attitudes towards suffering, suffering would have been good. Finally, I am not identifying another notion of "stakes" here beyond "what you should do." I also think the argument would fail for non-cognitivists who do not identify as quasi-realists, although I found those views harder to model.

4. Even if AGI had values lock-in, what about belief shifts and concept shifts? It is hard for me to imagine an AGI that was not continuing to gather new evidence about the world. But new pieces of evidence could dramatically change at least its instrumental values. In addition, new pieces of evidence / new experiences could lead to concept shifts, which effectively cause changes to its intrinsic values, by changing the meaning of the concepts involved. In one picture, for any concepts C and C*, C can shift over some amount of time and experience to have the intension currently assigned to C*. If you have that strong shifty view, then maybe in the long run even a population of AGIs with 'fixed' intrinsic values will tend to move around vast amounts of value space.

Also, regarding AGI lock-in, even if AGIs don't change their values, there are still several reasons why rational agents randomize their actions (https://web.stanford.edu/~icard/random.pdf). But chance behavior by the AGI dictator could over time allow for 'risks' of escaping lock-in.

5. Might be fruitful to engage with the very large literature on persistence effects in economics (https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/understanding_persistence_ada-ns.pdf). They might have models of persistence that could be adapted to this case.

Also curious what you guys would make of The Narrow Corridor by Acemoglu and Robinson, which gives a systematic model of how liberal democracies stably evolved through game theoretical competition between state and society. Seems like the kind of model that could be fruitfully projected forward to think about what it would take to preserve flourishing institutions. More generally, I'd be curious to see more examples of taking existing models of how successful institutions have stably evolved, and apply them to the far future.

6. I was a bit skeptical about the argument about Infernotopia. The issue is that even though utility is not bounded from below, I think it is very unlikely that the far future could have large numbers of lives with negative utility levels. Here is one argument for why: suppose utility is negative when you prefer to die than stay alive. In that case, as long as agents in the future have the ability to end their lives, it would be very unlikely to have large numbers of people whose utility was negative. The one caveat here is the specific kind of s-risk where suffering is adversarially created as a threat against altruists; I do think this is worth hedging against. But other than that, I'm having trouble seeing why there would be vast numbers of lives not worth living.