Authors: Joel McGuire (analysis, drafts) and Lily Ottinger (editing)

Formosa: Fulcrum of the Future?

An invasion of Taiwan is uncomfortably likely and potentially catastrophic. We should research better ways to avoid it.

TLDR: I forecast that an invasion of Taiwan increases all the anthropogenic risks by ~1.5% (percentage points) of a catastrophe killing 10% or more of the population by 2100 (nuclear risk by 0.9%, AI + Biorisk by 0.6%). This would imply it constitutes a sizable share of the total catastrophic risk burden expected over the rest of this century by skilled and knowledgeable forecasters (8% of the total risk of 20% according to domain experts and 17% of the total risk of 9% according to superforecasters).

I think this means that we should research ways to cost-effectively decrease the likelihood that China invades Taiwan. This could mean exploring the prospect of advocating that Taiwan increase its deterrence by investing in cheap but lethal weapons platforms like mines, first-person view drones, or signaling that mobilized reserves would resist an invasion.

Disclaimer

I read about and forecast on topics related to conflict as a hobby (4th out of 3,909 on the Metaculus Ukraine conflict forecasting competition, 73 out of 42,326 in general on Metaculus), but I claim no expertise on the topic. I probably spent something like ~40 hours on this over the course of a few months.

Some of the numbers I use may be slightly outdated, but this is one of those things that if I kept fiddling with it I'd never publish it.

Acknowledgements: I heartily thank Lily Ottinger, Jeremy Garrison, Maggie Moss and my sister for providing valuable feedback on previous drafts.

Part 0: Background

The Chinese Civil War (1927–1949) ended with the victorious communists establishing the People's Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland. The defeated Kuomintang (KMT[1]) retreated to Taiwan in 1949 and formed the Republic of China (ROC). A dictatorship during the cold war, Taiwan eventually democratized in the 1990s and today is one of the richest, freest, and highest functioning countries in the world.

Taiwan holds strategic importance due to its location, which threatens mainland Chinese maritime activities[2] as well as its dominance in advanced semiconductor manufacturing (~70%) – arguably the key bottleneck to building bigger computers on which to train ever more advanced AI models.

“The empire, long divided, must unite,” 分久必合 from Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

The PRC views Taiwan as a wayward province of China. The PRC would prefer to bring Taiwan back into the fold peacefully, as it did with Hong Kong.

But after Hong Kong’s administration returned to the mainland, the PRC demonstrated the hollowness of “one state, two systems” by steadily undermining Hong Kong’s promised autonomy, imposing a sweeping national security law, and silencing dissent through arrests, censorship, and political control.

Now, peaceful reunification seems less likely than ever before.

Part 1: Invasion — uncomfortably possible.

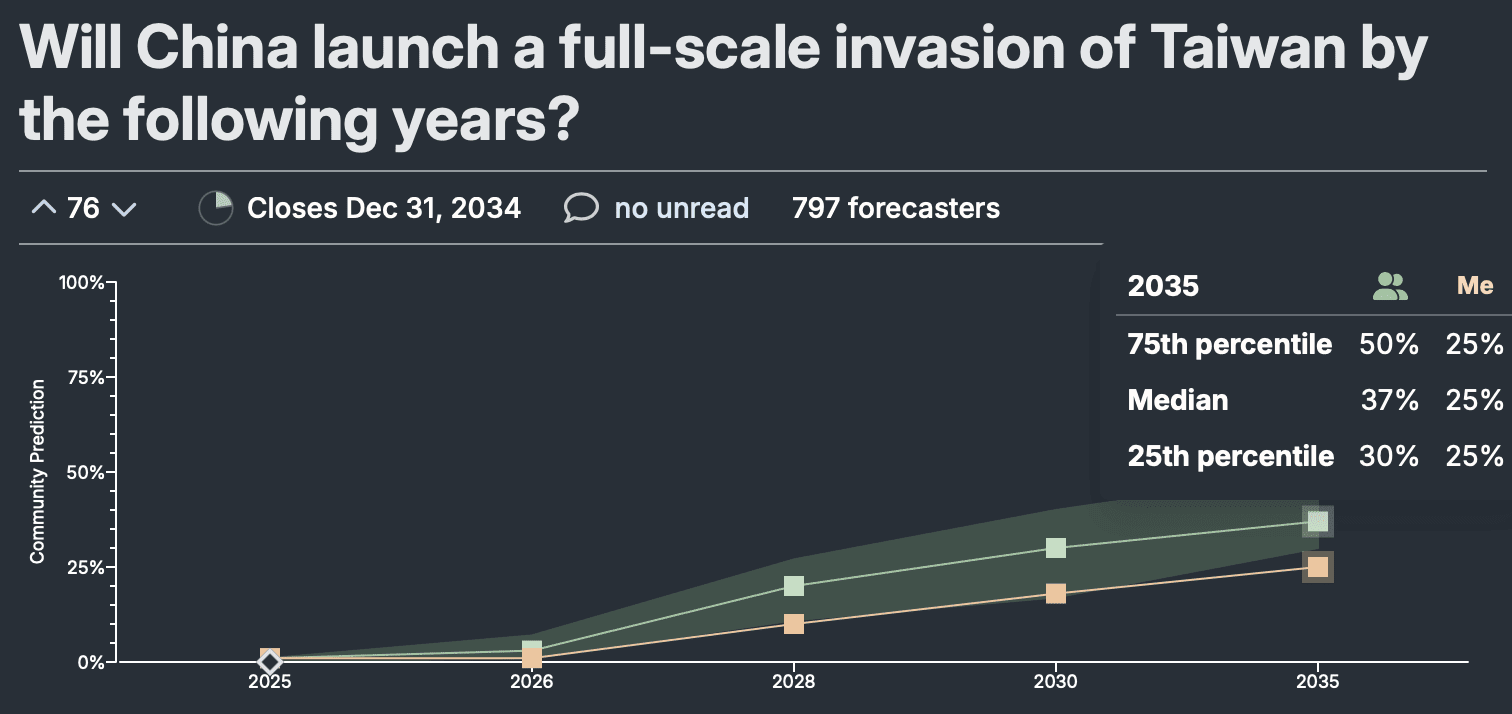

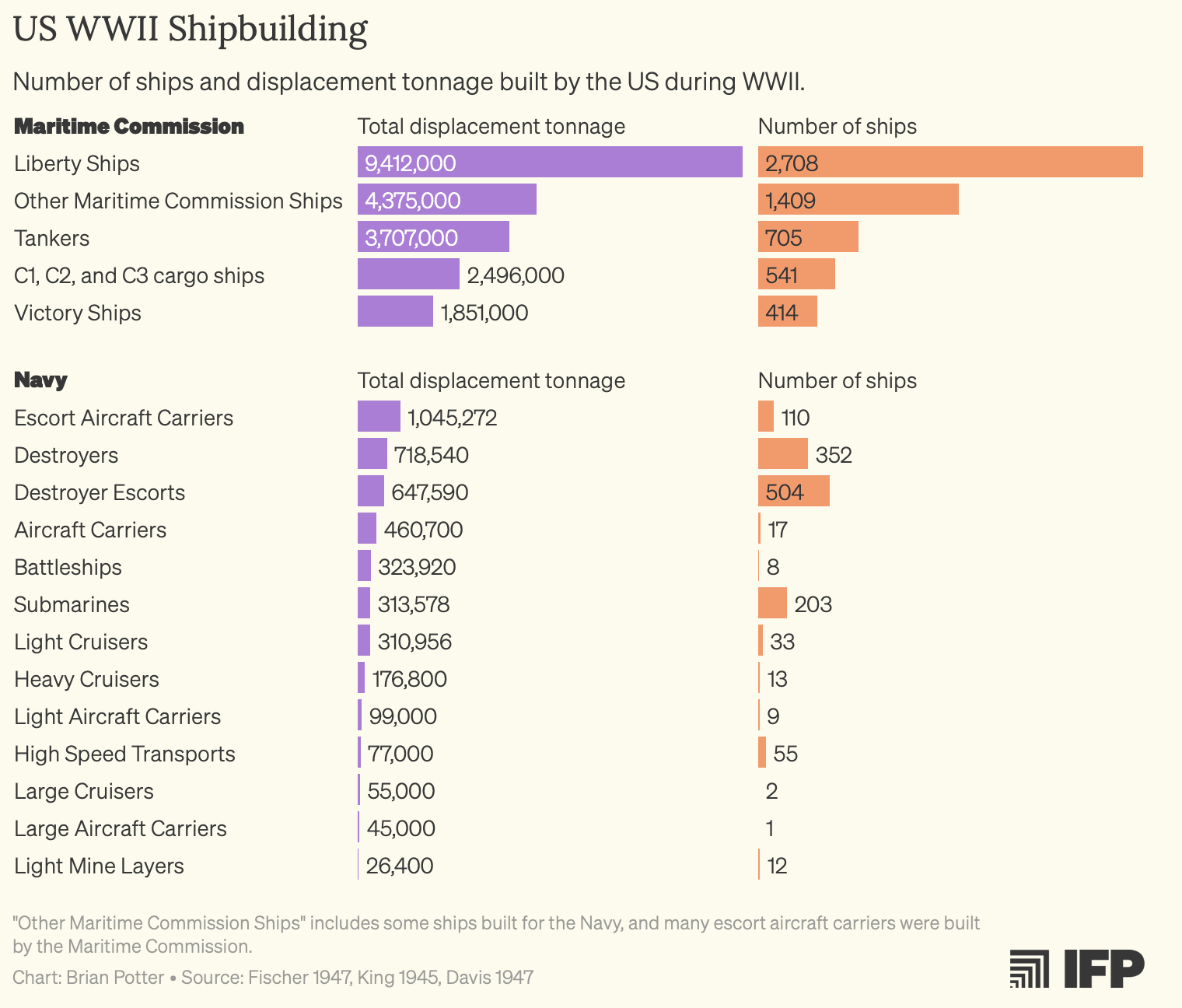

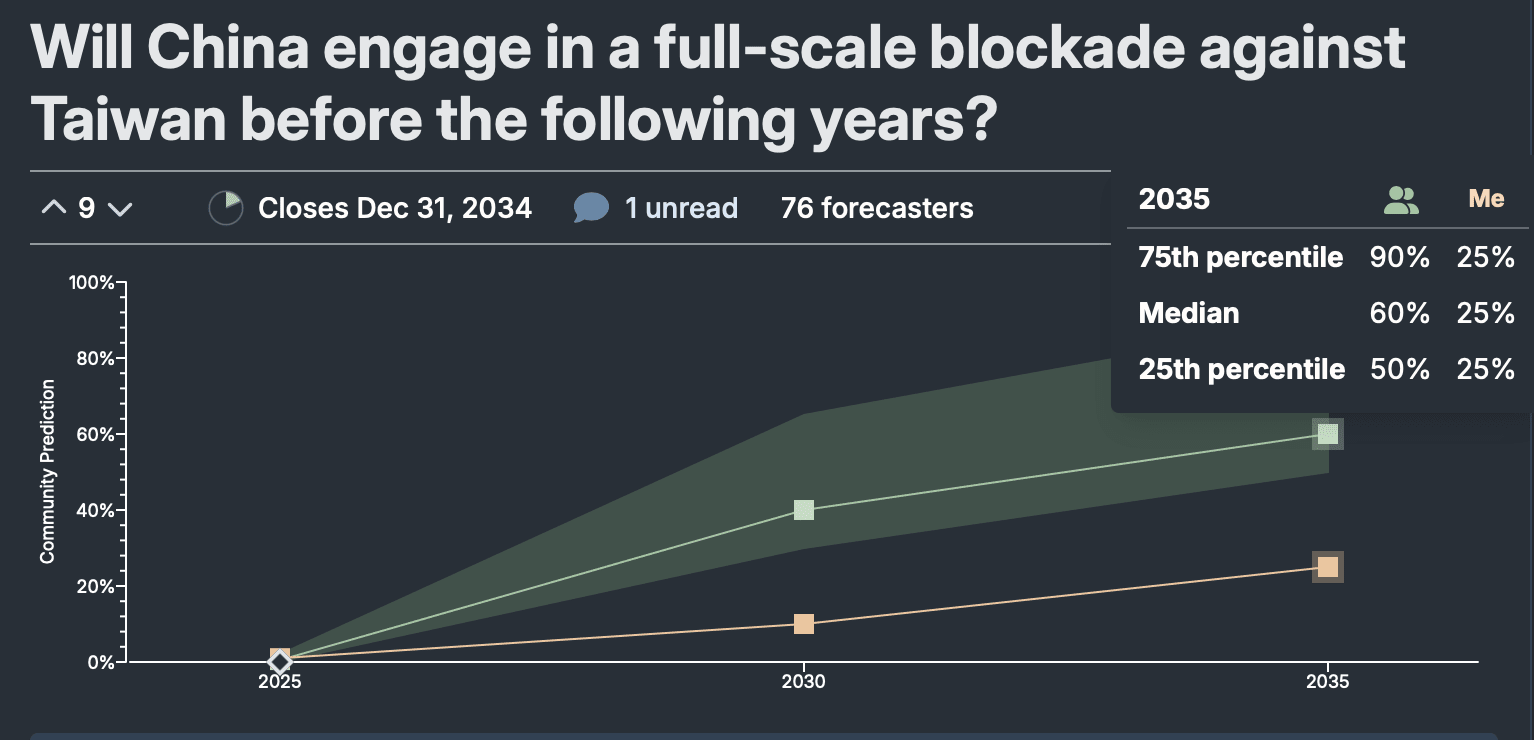

Forecasters (n = ~800) have the likelihood of an invasion of Taiwan within the next 10 years at 37%.

This estimate seems a little high to me (I am at 25%), but I will list the reasons I think that I think figures in this range are sensible.

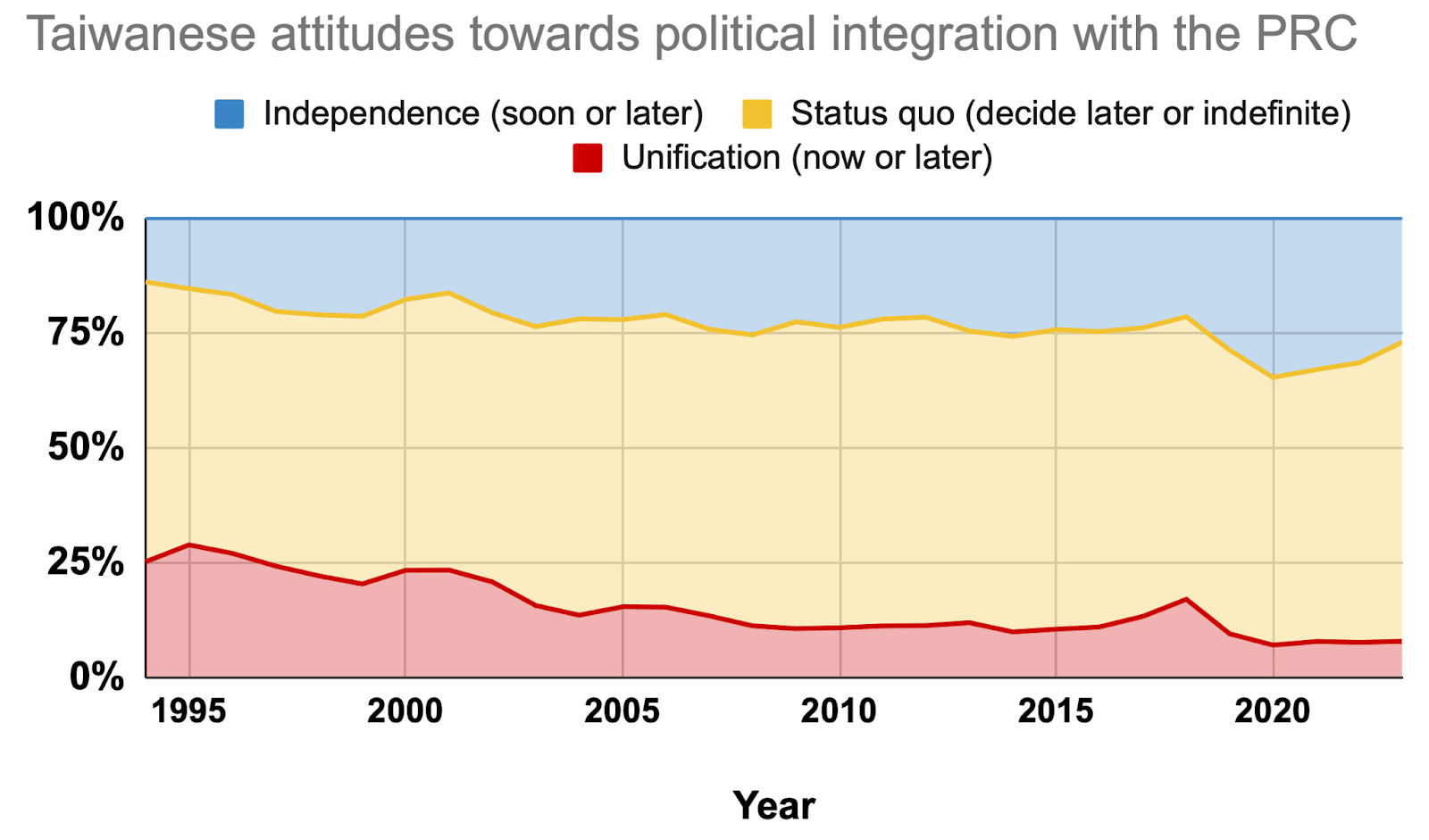

Reason 1. The Taiwanese people report historically low preference towards unifying with the mainland on any timeline.

Source: Authors own figure, using data from Election Study Center, National Chengchi University

Reason 2. Increasingly bellicose rhetoric and posturing from China

- “Complete reunification of our country must be realized, and it can, without doubt, be realized.” - Xi Jinping’s Speech at China’s 20th Party Congress in 2022.

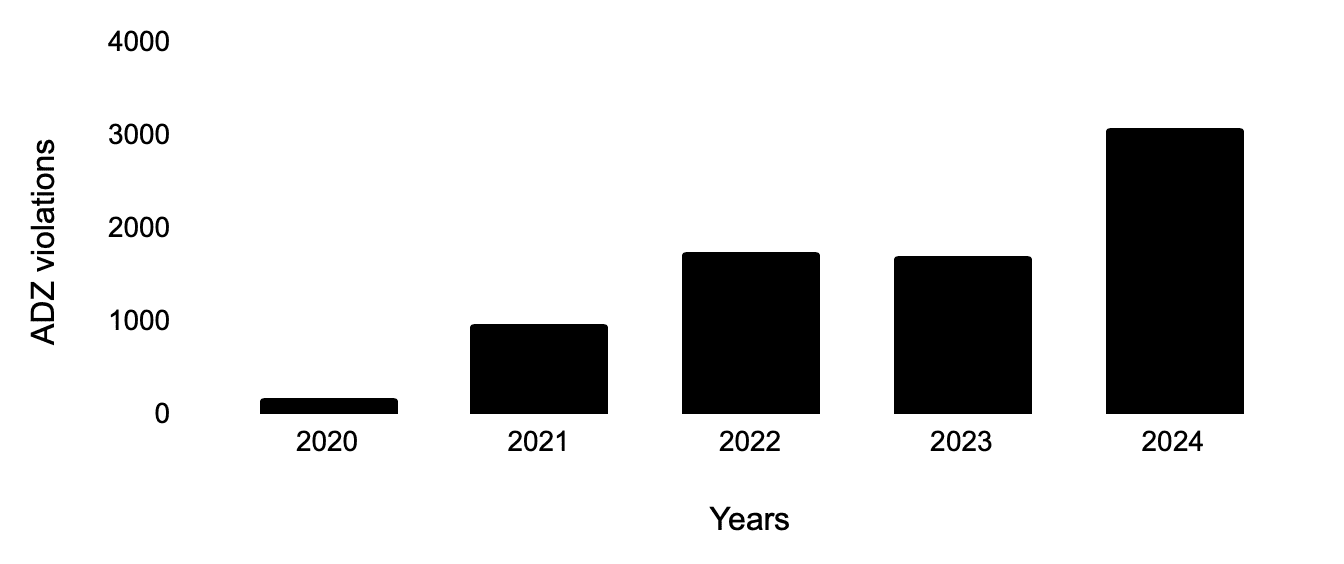

- Incursions into Taiwan’s air identification zone (ADZ), have increased dramatically in the past five years.

Source: Author’s own figure, using data from CSIS

Reason 3. Confidence from military and intelligence communities that China is preparing for an invasion.

- Former CIA chief said that the USA knew that as “as a matter of intelligence” that Xi had ordered his military to be ready to conduct an invasion of Taiwan by 2027.

- The Former US commander of the indo-pacific has similar concerns about a 2027 timeline (unclear if these views were independently arrived at).

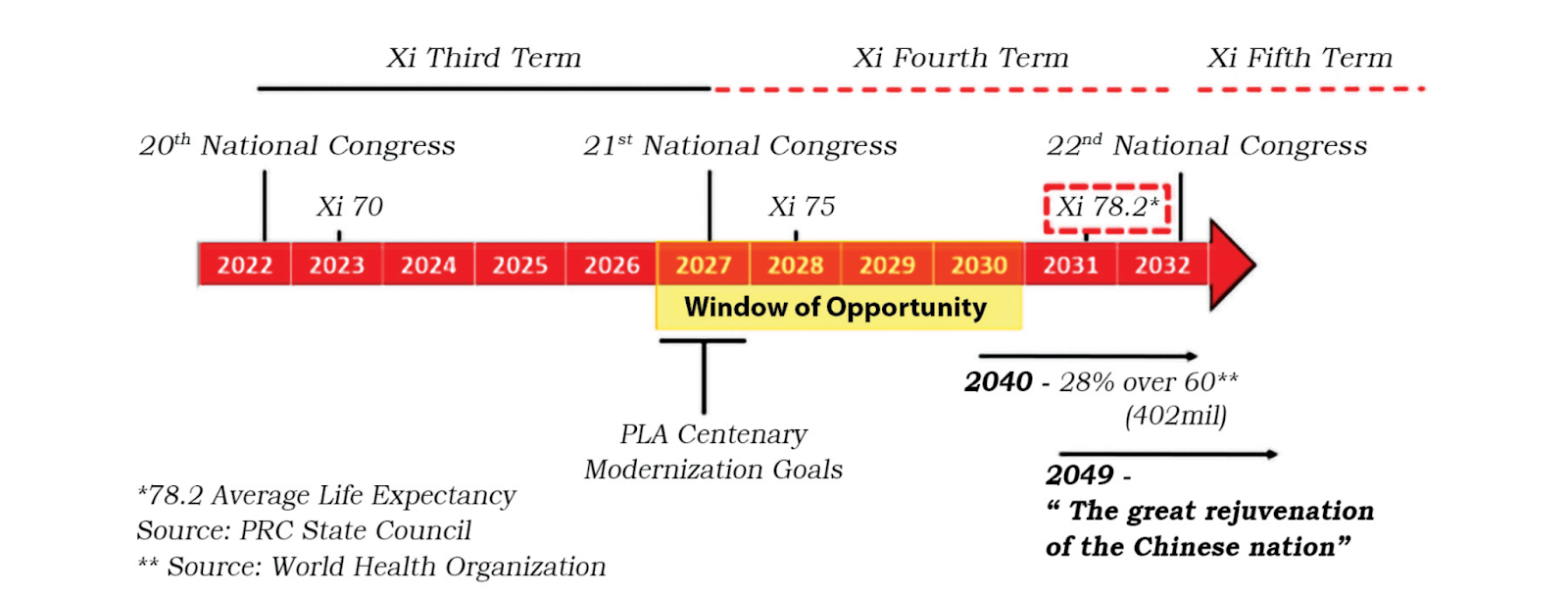

The closest China has come to a formal timeline is shortening the goal for reunification from hundreds or thousands of years to 2047[3], but several analysts seem to think the danger is front-loaded because 2027 represents the beginning of a relatively limited window of opportunity for China to invade.

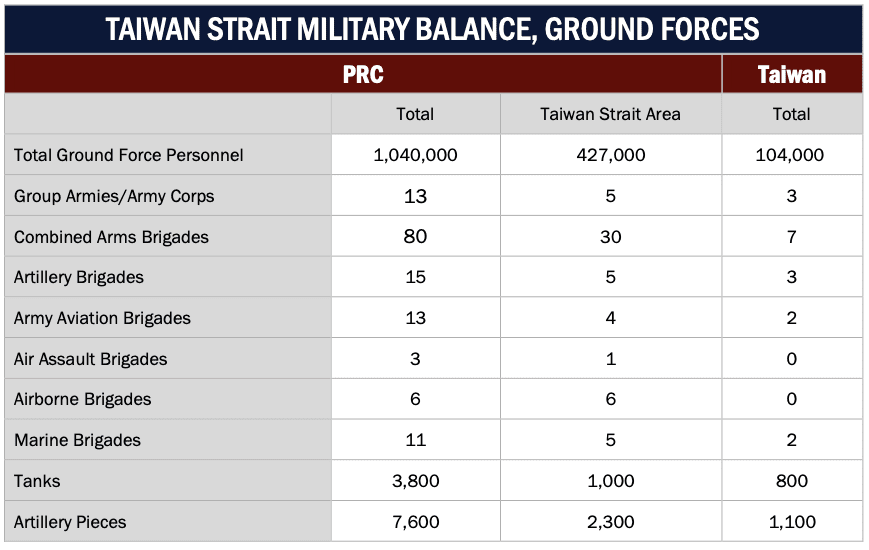

Source: Figure 1 from Amonson (2023).

The topic of timelines is debated. What is clearer is that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) appears to be preparing for the possibility of an invasion. These include acts such as:

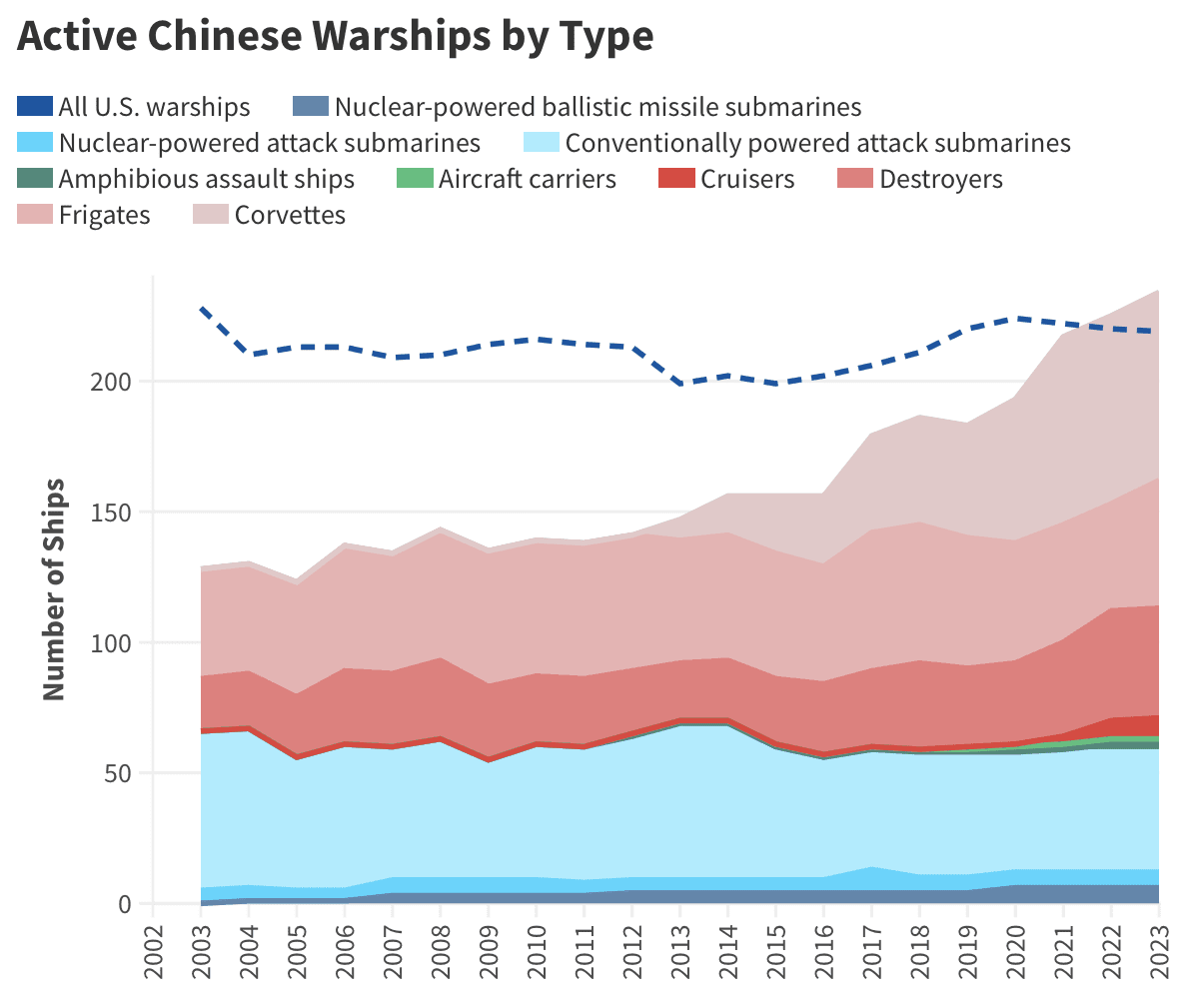

Reason 4. The PLA is building large-scale amphibious landing forces[4] (including high-capacity landing barges shown below) alongside its disproportionate investment in maritime forces.

Souce: CSIS; Note that the dashed line represents all U.S. warships

Source: China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S Naval War College

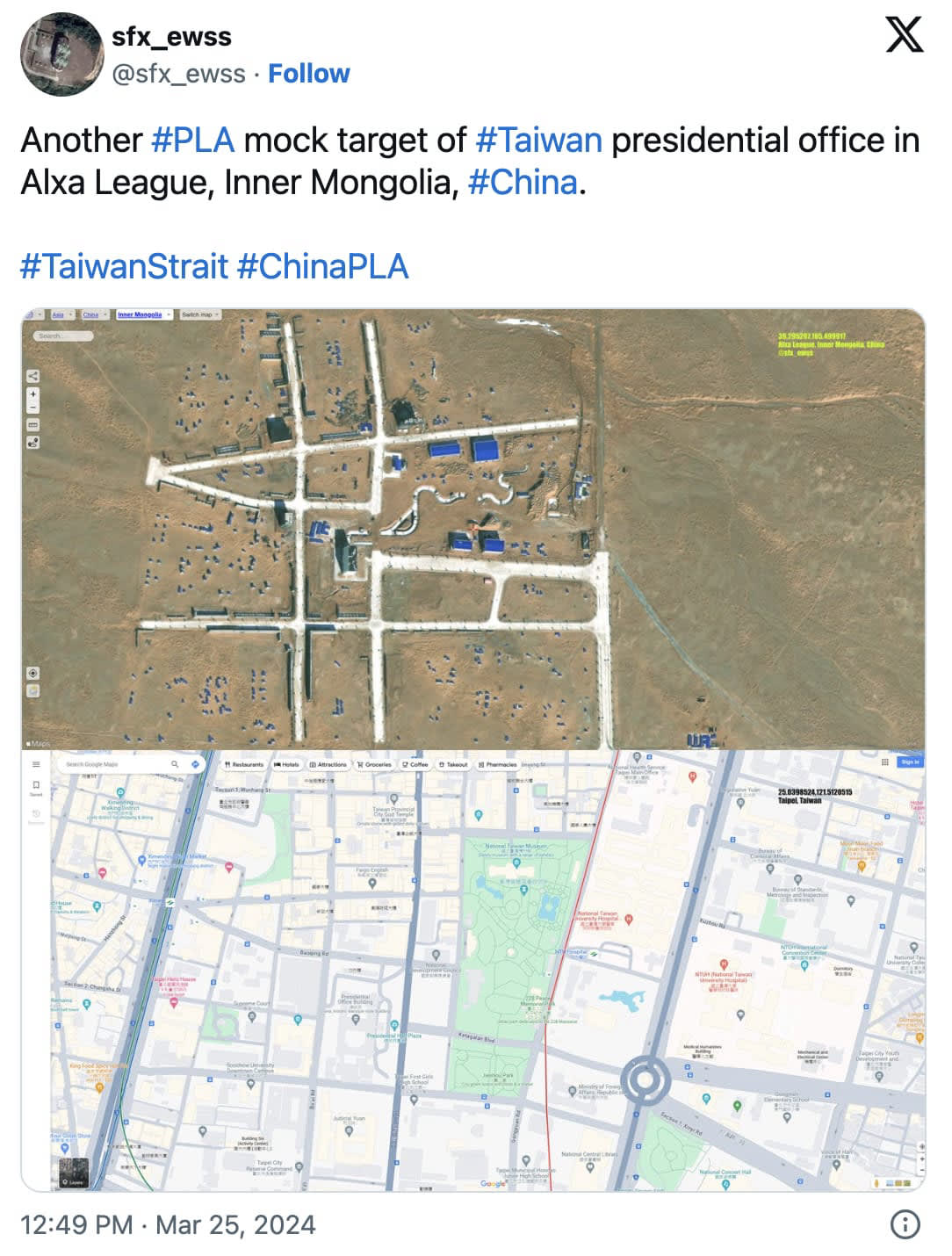

Reason 5. PLA simulates attacks on real locations such as energy infrastructure and conducts mock urban warfare drills in facilities resembling Taiwan’s Presidential Office.

Reason 6. Chinese stockpiling of minerals and resources to weather sanctions imposed in the case of a conflict.

Part 2: Why an invasion would be bad

Wars rend the fabric of society and even immiserate the victors[5]. A war over Taiwan could easily kill thousands and plunge the global economy into a recession, impoverishing millions. An occupied Taiwan could reasonably expect to become acquainted with midnight door-knocks, forced relocations, and reeducation camps. While these harms alone are worth preventing, the perils of an invasion do not end with the terror of occupation, the ruin of infrastructure, or the bleakness of lost liberty.

An invasion poses clear and catastrophic risks to all of humanity, particularly stemming from the involvement of the United States. Such a confrontation could:

- Trigger a hot war: Forecasters expect that an invasion could lead to a war with the USA (62%, I’m at 50%), which would increase the risk of nuclear war with the United States (my conditional estimate: 5%, ~1% unconditional).

- Seal in a cold war: If an invasion did not lead to hot war, I expect it could still end bilateral cooperation on global issues such as pandemic preparedness, management of emerging technologies like AI, and coordination on climate change. Through either cold or hot breakdowns in cooperation, I expect risks of a catastrophe stemming from the use or misuse of AI or biological weapons to rise (+0.6% absolute risk). Times of higher tension also elevate the risks of nuclear miscalculation (which my estimates do not account for).

- Spell the decline of the western-led liberal order: This could happen if the West fights and loses, or if it chooses not to aid a strategically valuable democratic partner, thereby losing credibility as a coalition. I do not account for the disvalue of this quantitatively.

2.1 War and nuclear war

Forecasters on Metaculus predict there is a 62% chance the US will intervene if Taiwan is invaded. This seems high given that it implies there is a greater than even chance that the Trump administration would support US military involvement. The current administration appears considerably more isolationist and far less willing to intercede on behalf of other nations than recent administrations, which have explicitly claimed that the US would defend Taiwan[6].

I estimate a lower likelihood of intervention at 50%. One of the main reasons this figure is not lower is that US involvement may be forced if US assets are attacked preemptively. China has clear incentives for launching a preemptive assault — namely, removing US and allied capabilities would potentially buy time for China to overwhelm Taiwan in the weeks or months it would take the USA and its partners to mobilize their forces.

Nuclear war

I think that a nuclear war springing from a US-China conflict over Taiwan is unlikely (0.9%). But even a “limited” nuclear war could kill hundreds of millions to billions, and I don’t expect a nuclear war between the USA and the PRC to employ anything less than a sizable proportion of their shared stockpiles of thousands of warheads. Unless the world changes course, I expect millions will die as a result of an invasion of Taiwan.

Where does this 0.9% number come from?

→ 37% chance of invasion × 50% USA intervenes × 5% nuclear risk = 0.9% nuclear war

The first two inputs are based on forecasts from a community of forecasters. The last guess is my own, so I’ll try to defend it briefly.

5%, Why so low?

Mutually assured destruction holds. Presumably we will not be dealing with Maos[7] or McCarthys next time around. After the chaos of the start of the conflict, I expect the limits to be established relatively quickly (as was clearly the case with Ukraine). Once this brief window has passed (a day or a week), the risk of escalation decreases.

I expect each side would have at least some incentive to keep the war away from its own territories[8]. If they succeed at geographically compartmentalizing the conflict, I think nuclear escalation would be less likely.

Past proxy wars between great powers (Vietnam, Afghanistan, Korea, Ukraine) as well as limited conventional conflicts between nuclear powers (Kargil War, Sino-Russian border war of 1969, and Sino-Indian border clashes) provide precedents for (mostly indirect) conventional conflict between great powers to remain conventional.

Less relevant but still related are the cases in which nuclear armed powers have declined to use nuclear force despite the prospect of potentially politically devastating defeat (Israel at the beginning of the Yom Kippur War, Russia during the Kharkiv offensive, US in Vietnam, China in Vietnam, US during the Chinese offensive in Korea, the Soviet Union in Afghanistan[9]). These cases provide a precedent for great powers treating their nuclear capabilities with restraint.

Further, I expect a war over Taiwan would not be perceived as existential for either state. Whether the leader of the PRC sees it as existential for their rule is another question. Neither state wishes to eradicate the other. This was not even the case during the Cold War, when the sides seemed more ideologically opposed and far less interdependent.

5%, Why so high?

The risk of miscalculation remains. And wars escalate.

I view my conditional 5% as mostly being accidental or due to uncontrollable escalation.

Accidents happen. We can imagine China or the USA misinterpreting a conventional strike as attempting to potentially allow for a nuclear strike. For example, the USA launches a conventional strike to neutralize Chinese anti-ship missiles to protect US carriers, but this also takes out PLA nuclear armed missiles. This may lead China to put its nuclear forces on high alert, which the USA then misinterprets as a prelude to a first strike, thus triggering a preemptive nuclear attack. We can imagine similar tragedies regarding conventional strikes on any dual-use weapon (e.g, loss of nuclear equipped submarines or early warning satellites is seen as an attempt to undermine nuclear deterrence).

There are countless ways accidents can happen, and the fog and chaos of war does not make accidents any less likely. See the times nuclear war nearly occurred due to geese, clouds, drunkenness, solar flares, or insertion of the wrong floppy disk.

Beyond accidents, I think a likelihood around 5% is plausible because the dynamics of escalation are not well understood. As Braumoller argues (2019, summarized by Clare and Martin, 2022), most wars are small, some are extraordinarily deadly. This implies there is no clear upper bound to the badness of war. Every time you start a war there seems to be some chance it will swallow the world.

Other predictions for nuclear war conditional on a crisis

- Hellman (2021) predicted a 6.7% chance that events like the Cuban missile crisis escalate to nuclear war.

- The 5% figure is the same as Peter Wildeford’s prediction that “I take a ~5% chance that any given incident will escalate into a nuclear exchange causing at least one fatality”.

- Sentinel forecasters predicted around a ~1% chance that a conflict (1k or more deaths) between Pakistan and India would escalate to the nuclear level.

- This is related to the base rate of 1 instance of use out of the last 80 years (1.25% per year) – see Rodriguez et al., (2019) for more discussion.

- However, if you condition on a nuclear power engaging in a conflict (1 in ~40?) or situations in which actors considered using nuclear weapons in a conflict or near conflict (1 in ~10), the base rates seem higher.

Sanity check

If you believe the 0.9% figure, is it sensible that this discrete risk constitutes 12-23% of the total risk of a nuclear catastrophe until 2100?

Superforecasters and domain experts predict that there is a 4-8% chance that a nuclear war will kill over 10% of the population before 2100 (p. 16, Karger et al., 2023).

I think these forecasts are plausible, and that they are the most reasonable publicly available estimates. This implies that the risk I have specified makes up a large share of the nuclear risk over the next 100 years. Is this sensible?

I think it is. That’s because:

- I think the greatest risks for nuclear war stem from direct conflict between the great powers. With the greatest concerns being the NATO-Russia, US-China, India-Pakistan, US-North Korea, and India-China dyads.

For example, if I decompose this risk by estimating that 70% of the nuclear risk comes from direct conflict and 30% of the risk stems from the US-China dyad[10]. This would imply 20% of the risk comes from a conflict over Taiwan. This strikes me as sensible and coherent with the other forecasts of nuclear risk.

I expect India to become a great power and remain an adversary of China. The more powerful India becomes with respect to China, the more hesitant China will be to engage in a conflict and risk getting pinned by India. This makes me think China has a window of opportunity to risk a high intensity great power conflict over the course of the next 10 years. This is a specific example of a general problem that China (or any other great power) faces. The more hegemonic, arrogant, and undiplomatic you become, the greater the likelihood a coalition is formed against you. This seems more a problem the more surrounded you are by potential adversaries[11].

- I think once the Taiwan question is settled, the other opportunities for conflict between the US and China seem less probable, and less likely to spark a direct hot war (Korean War 2?).

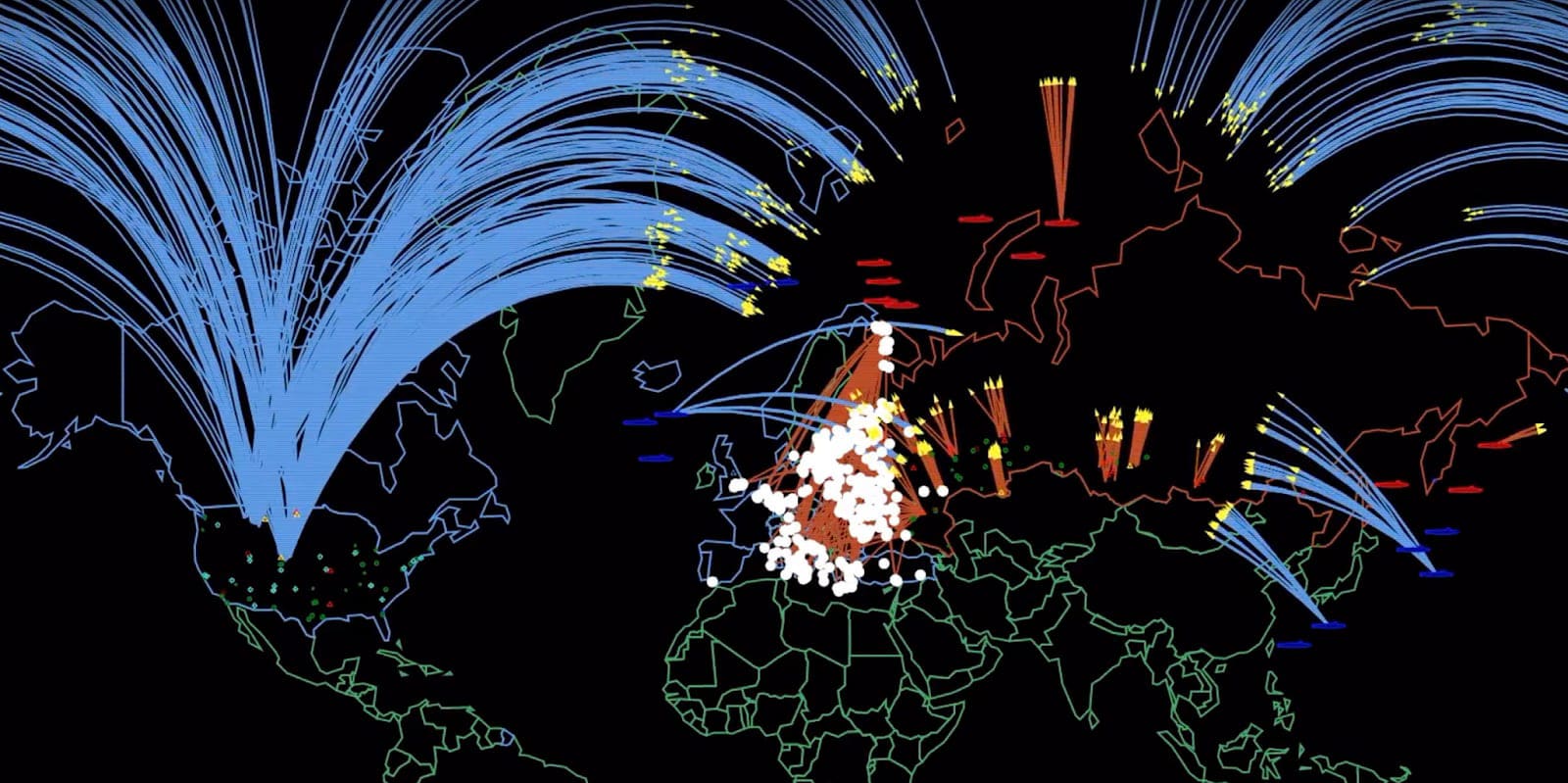

Source: PLAN A | Princeton Science & Global Security

2.2. The end of cooperation: AI and Bio-risk

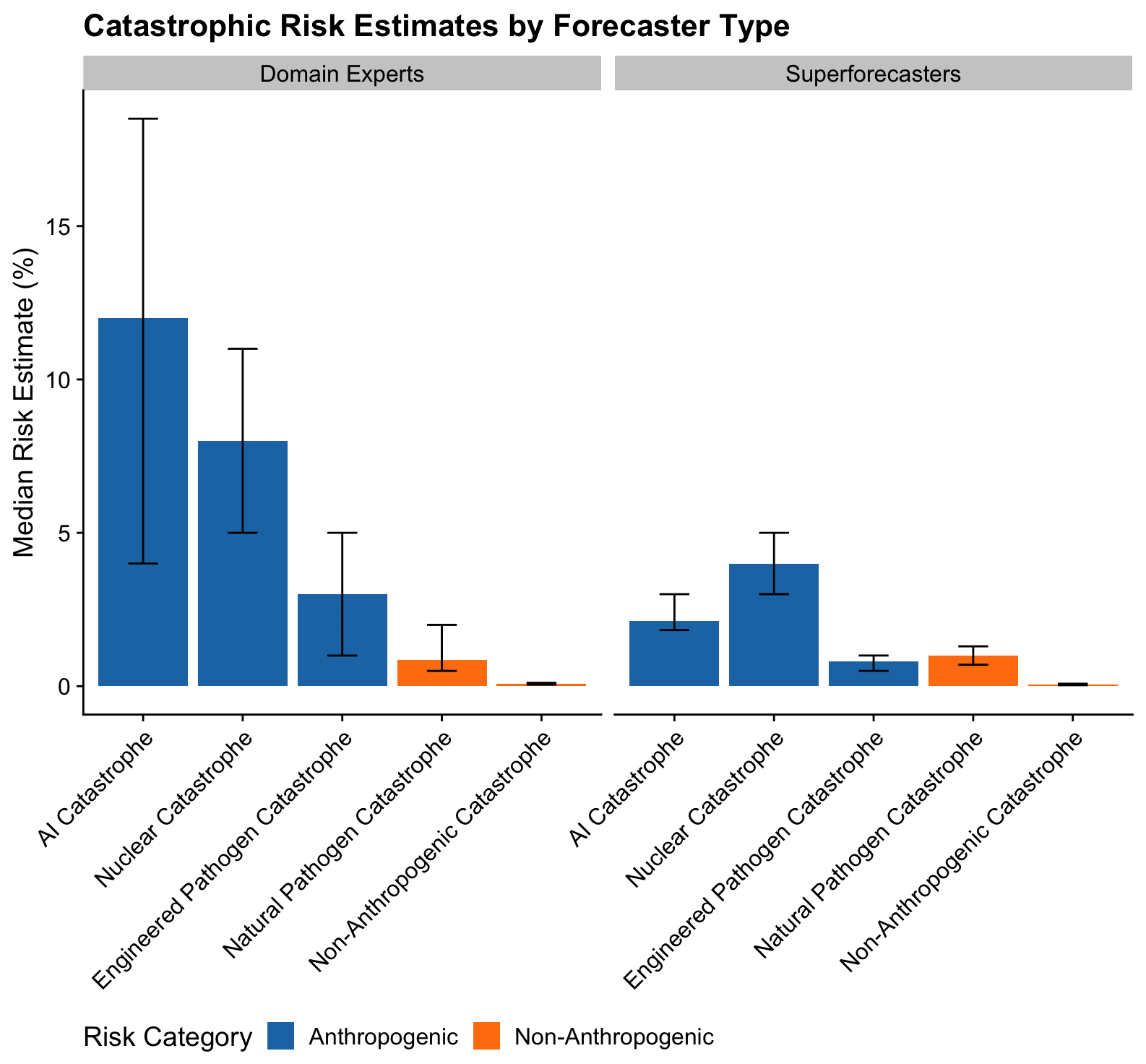

After nuclear risks, domain experts and successful forecasters (“superforecasters”) think that the likeliest source of a global catastrophe that kills at least 10% of the population before 2100 comes from two sources:

- risks posed by artificial intelligence (Experts: 12%, superforecasters: 2%) and

- a pandemic (Experts: 1.8%, superforecasters: 3.8%) (p. 16, Karger et al., 2023).

I’m not considering the direct risk from the use of AI or biological catastrophes being triggered because of a hot war, but such risks aren’t unthinkable. A war would presumably foster strong incentives to fast track AI or biological weapons, which could lead to escalation and world-shattering consequences.

Rather, I am thinking of the risk as primarily due to a breakdown in cooperation that would otherwise happen to avert such risks.

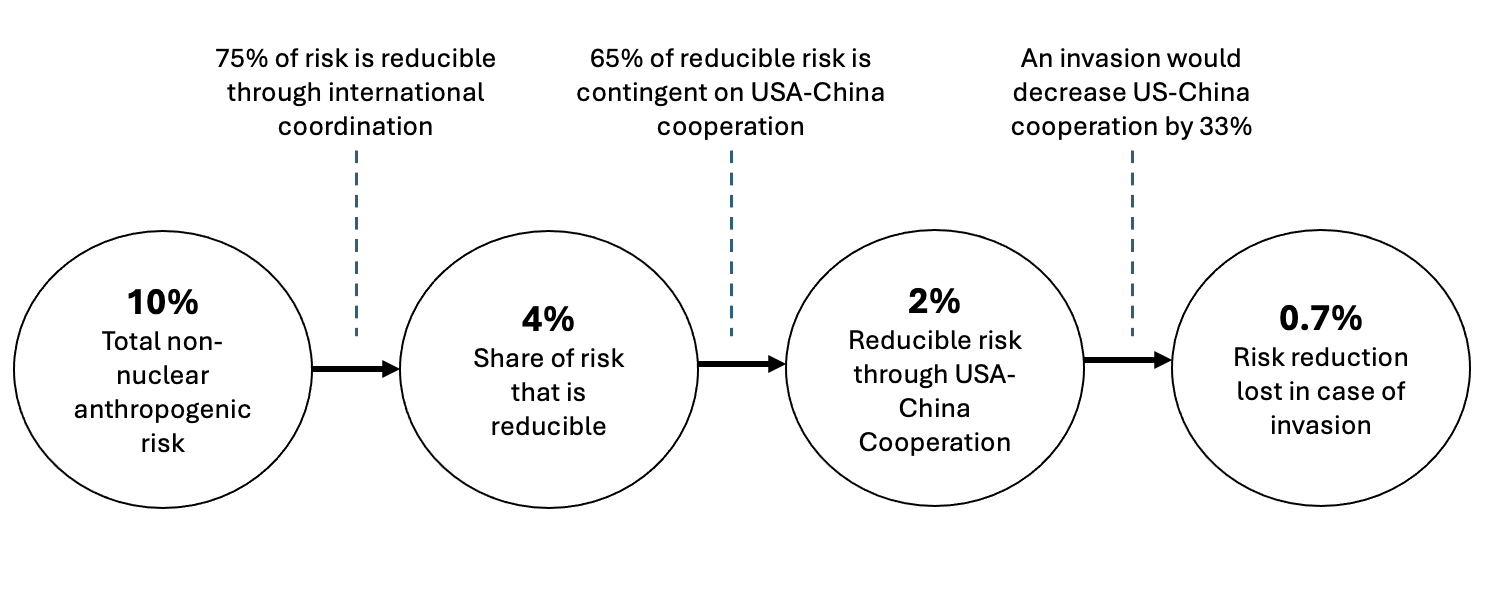

I think the likelihood of biological and AI catastrophes are an average of superforecasters and domain experts: AI = 7% and biological = 3% (total non-nuclear human caused catastrophic risk = 10%)[12].

To demonstrate with a forecast, let’s make up some numbers.

- Let’s assume that some amount of the total AI + Bio risk (40%) as reducible.

- Assume that 75% of this reducibility is through international coordination.

- Assume that 65% of the risk reducible through international cooperation is contingent on US-China cooperation.

- That implies 2% percentage points (20% of the 10%) of the risk is potentially reducible due to US-Chinese cooperation on AI and biological risks.

Assume that the prospects for cooperation would decrease drastically (33%[13]) if there was an invasion. My guess is this represents a 0.64% increase in the likelihood of catastrophic risk.

A direct conflict is not necessary to stifle cooperation. Tension over Taiwan has already threatened to end US-Chinese cooperation on other critical global issues like climate change. An analogy is US-Russian relations during the Russo-Ukrainian war. It seems as if as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian war, cooperation ceased on the New START Treaty. The treaty had probably decreased the amount of nuclear weapons each country deployed.

A cold war would still decrease bilateral cooperation and accelerate longer term arms race dynamics.

2.3 Appeasement or capitulation and the end of the liberal-led order: Value risk

Just as the Allied victory in the second world war created institutions that fostered global cooperation and democratisation, a defeat or abandonment of Taiwan could alter the trajectory of global institutions. I agree with the views of Clare (2023) when he described the less legible impacts of a great power conflict:

Major conflicts reshape the global balance of power. In their aftermath, leaders of the victorious nations often use their new influence to change various institutions in their favour.

They redraw borders and cause civilisations to rise and fall. They invest in military research and influence how technological change happens. And their diplomatic strategies shape the norms and institutions that structure the international system.

Such changes can have very long-lasting effects.43 In extreme cases, they can even change our civilisational trajectory: the average value of the world over time. This might sound abstract, but just think about how much more pessimistic you’d feel about the future if more of the world’s most powerful countries were still ruled by fascist dictators.

A new great power war has the potential to cause similarly important changes to global institutions. For example, if an authoritarian state or alliance emerged from the war victorious, they may be able to use their influence and modern digital surveillance tools to entrench their power at a global scale.

These risks apply to an invasion of Taiwan. It is tempting to say the risks of a catastrophe are too high, and the world would be safer if the USA and its allies let China conquer Taiwan. But inaction is not costless either.

The loss of Taiwan would further divide and demoralize the alliance of democracies that have had unprecedented success in creating prosperous, peaceful, sustainable, and happy societies. A victory for the CCP over the West would embolden more policymakers to pursue strong, personalistic, and centralized authority. And why not? The CCP will have not only shown that it can build while the west’s weak democracies squabble, but also that it can be victorious in warfare, the ultimate test of state capacity.

More concretely, the most common concern about letting a country fall is feeding the appetite of an imperial power. While it is hotly debated, the PRC seems distinctly less imperial in its territorial ambitions than Russia or other European powers at their grabbiest. I doubt the subjugation of Taiwan would mark the beginning of a period of conquest. But it could certainly encourage the PRC to iron out its ambitious (and still internationally unrecognized) claims to the South China sea or to engage in some lite Soviet style adventurism to prop up or establish friendly regimes.

That said, I think the clearest risk of capitulation would be opening the door to further acts of aggression by other powers. Particularly, I imagine that a successful invasion of Taiwan could embolden Russia to launch another invasion of a neighboring state, or it could provide an opportunity to break NATO once and for all by occupying a few square miles of Latvia or Estonia to create a Türkiye-Syrian style buffer zone for the ethnic Russians that, according to the Kremlin, are at risk of persecution.

Part 3: How to prevent a war

The chances of war are difficult to depress. But the deterrence gap between China and Taiwan seems small enough to close. The potential role philanthropy could play seems highly uncertain, and on its face trifling, however, the stakes are high enough I think it would be foolish to dismiss the possibility without further research and investigation.

First, I’d like to address the anticipated objections about working on this as a problem. Avoiding a war over Taiwan is a specific case of avoiding potential great power conflict. The best and most extensive work I’ve seen on prioritizing great power conflict risks is by Stephan Clare (2023). His major concerns with working on this as a cause area are:

- There are many people working on avoiding war, with strong incentives to do so. (More.)

- Even if you can influence policy, it’s often not clear what the best thing is to do. (More.)

- Maybe it’s better to focus instead on specific risks.

I’ll address these in turn.

- There are many people working on avoiding war, with strong incentives to do so.

I agree this area definitely isn’t neglected. But I don't think this is a strong enough reason alone to avoid working on the problem. I’m not sure that every avenue to try and prevent an invasion of Taiwan has already been articulated. I think there are potentially important ideas that haven’t yet been explored or given a sufficient push. The importance of this problem seems sufficient that we should at least try and have a sense of what the best options are before abandoning work on them.

- Even if you can influence policy, it’s often not clear what the best thing is to do.

In the sub-heading Clare restates this as:

“There aren’t many possible actions which are clearly positive”

I agree that policies to decrease conflict in general are often unclear whether they typically lead to a more peaceful or dangerous world. Does arming decrease aggression in adversaries, or increase the incentives to use force or provoke a race dynamic? However, considering the case of Taiwan, I think there are several policies that seem clearly positive.

I’ll briefly outline two options here before going into more depth. In this section I draw heavily on McKinney and Harris (2024), which is the best treatment I’ve seen of the topic.

Diplomacy: The Taiwanese and US governments could decrease the likelihood of an invasion by making credible commitments to the status quo — that is, that Taiwan will not seek to formally declare independence. Pursuing this strategy seems to have low downside risk.

Increasing deterrence (military and economic): The Taiwanese government can credibly make the cost of an invasion so high that China doesn’t consider it. This has some downside risks, but I think those are relatively minor.

- Maybe it’s better to focus instead on specific risks.

Perhaps it’s true that focusing on specific risk scenarios would do a better job at surfacing tangible solutions to potential catastrophes (e.g. AI or biological weapons), I think the same benefits of focus can stem from imagining the likeliest scenarios for great power conflict. Instead of asking, “How do we prevent great power war or nuclear armed conflict?” we should ask, “How do we deter Russia from invading the Baltics?” or, “How do we tame tensions between Pakistan and India?” or, of course, “How do we temper China’s appetite for Taiwan?”.

3.1. Diplomacy: speaking softly

The clearest viable diplomatic path to peace seems to be through reassuring China that Taiwan will not seek independence. This would decrease the cost of inaction for the PRC. China seems to fear that Taiwan is increasingly likely to declare independence[14] which would increase the diplomatic costs of a later invasion[15].

However, the obvious issue is that democracies get to change their minds. That could be made more difficult by, for example, enshrining the status-quo in a constitution for a certain amount of time (50 years). Something like this seems conceivable, but unlikely.

Another diplomatic option to decrease tensions would be avoiding purely symbolic but inflammatory gestures on the USA’s part, like Nancy Pelosi visiting Taiwan. This seems like a clear way to lower the temperature without doing anything to undermine Taiwan’s ability to defend itself (this has been argued by Gomez, 2023).

There are other diplomatic options that now seem unviable or unpersuasive. If the PRC had actually allowed Hong Kong to stay autonomous, then there would be a potential path towards peaceful unification, but that seems unfeasible now unless China reverses course in Hong Kongand credibly commits to “One Country, Two Systems.”

Some also suggest it would increase the cost of an invasion if Western countries made credible commitments to recognize Taiwan’s sovereignty in response. But I do not see the sense in this. It seems like it would do little to deter China. It would only impose a cost if the PRC failed. And who plans to fail? Not Xi.

3.2. Deterrence: carrying a big stick

Taiwan can increase the expected costs of invasion by investing heavily in defensive capabilities and increasing its ability to effectively mobilize reserves in the case of a conflict.

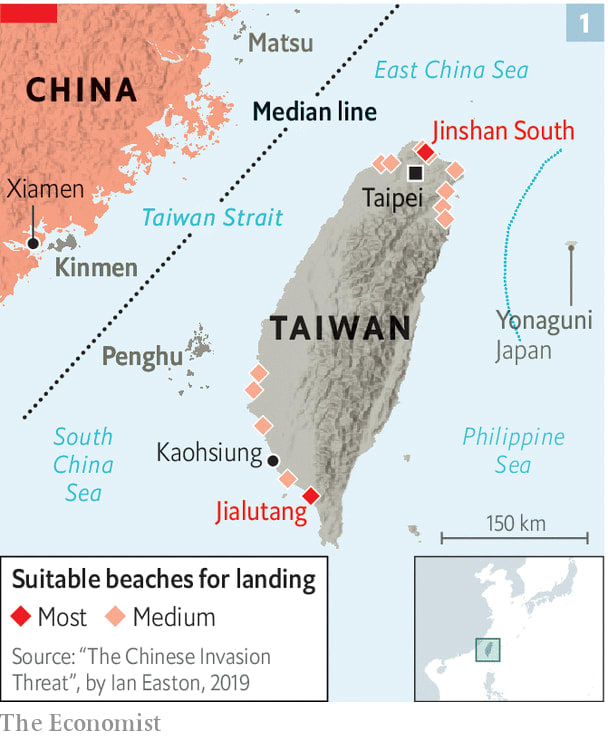

Invading Taiwan is hard. Consider that:

1) Amphibious invasions are known to be amongst the hardest military manoeuvres. The US department of defense says (2024):

“A large-scale amphibious invasion would be one of the most complicated and difficult military operations for the PLA, requiring air and maritime superiority, the rapid buildup and sustainment of supplies onshore, and uninterrupted support. It would likely strain the PRC’s armed forces and invite a strong international response. These factors, combined with inevitable force attrition, the complexity of urban warfare, and potential for determined resistance, make an amphibious invasion of Taiwan a significant political and military risk for Xi and the CCP, even assuming a successful landing and breakout past Taiwan beachhead defenses.”

2) The strait of Taiwan is wide and windy, and Taiwan doesn’t have many ports, beaches, or natural harbours (see this CFR article for a vivid illustration of these points).

3) An invasion fleet is hard to conceal, which guarantees weeks of forewarning prior to the invasion. Before the invasion of Ukraine, the identification of blood supplies (which will ruin quickly) moving to the front indicated that an attack was imminent. There would be similar and likely even less ambiguous signs before an amphibious invasion (which would also be even costlier to fake).

4) The rule of thumb for offensive operations is to maintain a 3-to-1 force ratio advantage. Maybe more for storming rocky, jungled islands — when the USA planned on invading Taiwan in WW2 they were aiming for a 4-to-1 to 10-to-1 ratio. Taiwan’s military is composed of ~100k ground forces, which means that the PLA will need to land at least ~300k troops in short order to take the island before any potential allied reinforcements arrive or Taiwanese conscripts are mobilized.

The cost of invasion is already high. It seems exceedingly plausible that with the right investments, Taiwan alone could increase the costs of invasion sufficiently to safen it considerably.

Toy model of deterrence

To start thinking about how increasing deterrence could work, let’s consider a simple model of deterrence. The key assumption is that if Taiwan is able to field a force large enough to make a 3 to 1 ratio impossible, this will dissuade China from invading. To empirically interrogate this assumption, I can imagine looking for or performing studies of wars that did and didn’t happen based on the balance of forces.

Unsurprisingly, the PRC has a huge advantage over Taiwan in terms of active personnel.

If we only go off the active duty personnel in the Taiwan Strait area, China would have around a 4 to 1 force ratio (assuming no outside intervention or activation of reserves). But presumably China would be willing to commit up to a similar ratio of its total forces that Russia has been willing to commit in Ukraine (50-80% of its Army). If we assume 65% of PLA forces are committed, that translates to an invasion force of ~650k. To deter this force, Taiwan would need to be able to credibly field at least 650k / 3 = ~200k troops, which means doubling the size of its ground forces.

Let’s be conservative and imagine that doubling Taiwan’s ground forces requires doubling the defense budget. Taiwan could feasibly come up with the cash to make this happen. Sure, it would require a considerable amount of political capital, as it’d probably mean sacrificing other budget items (although Taiwan’s debt to GDP seems relatively low at ~30% so they could potentially finance it for at least a good part of the window of danger).

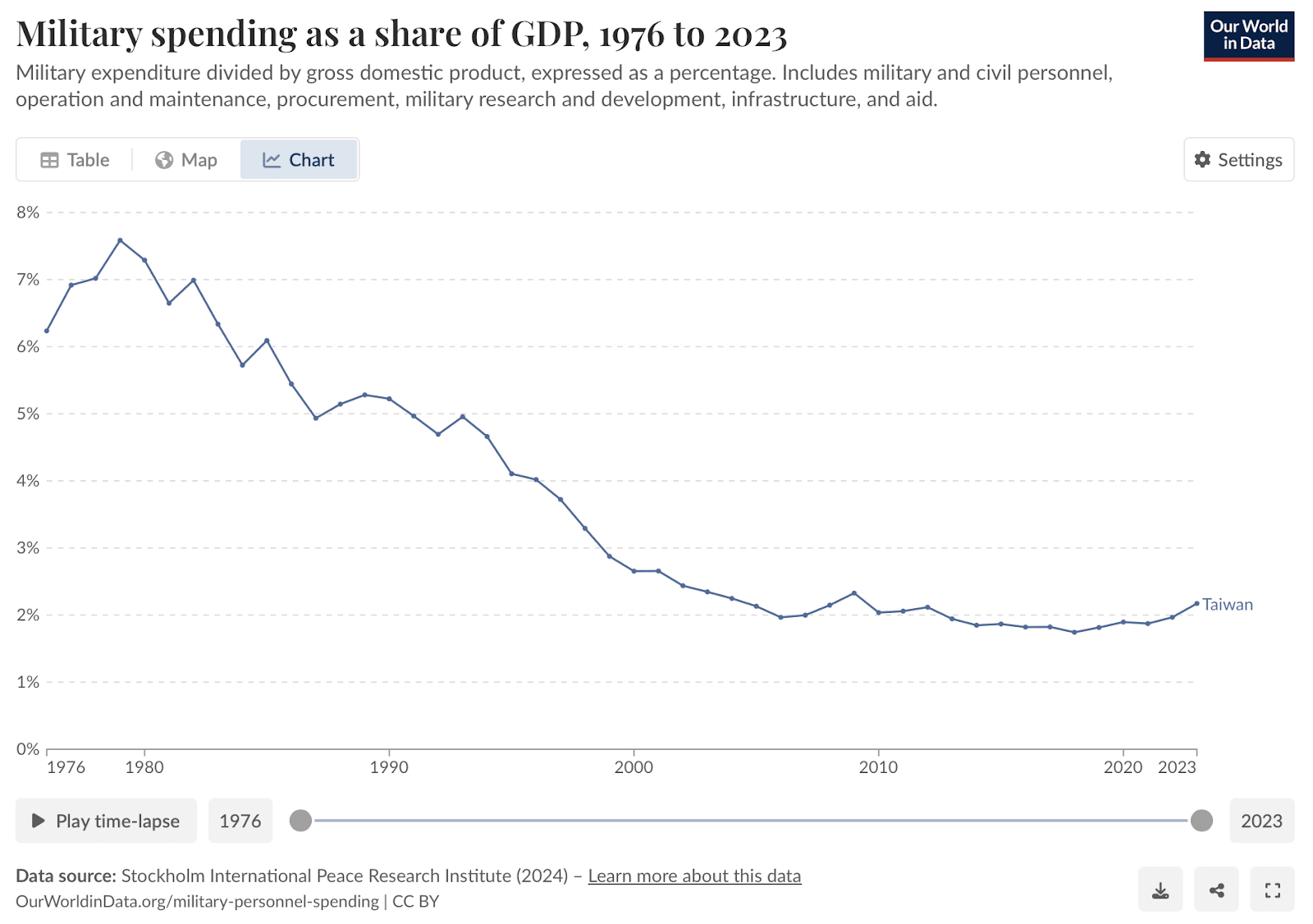

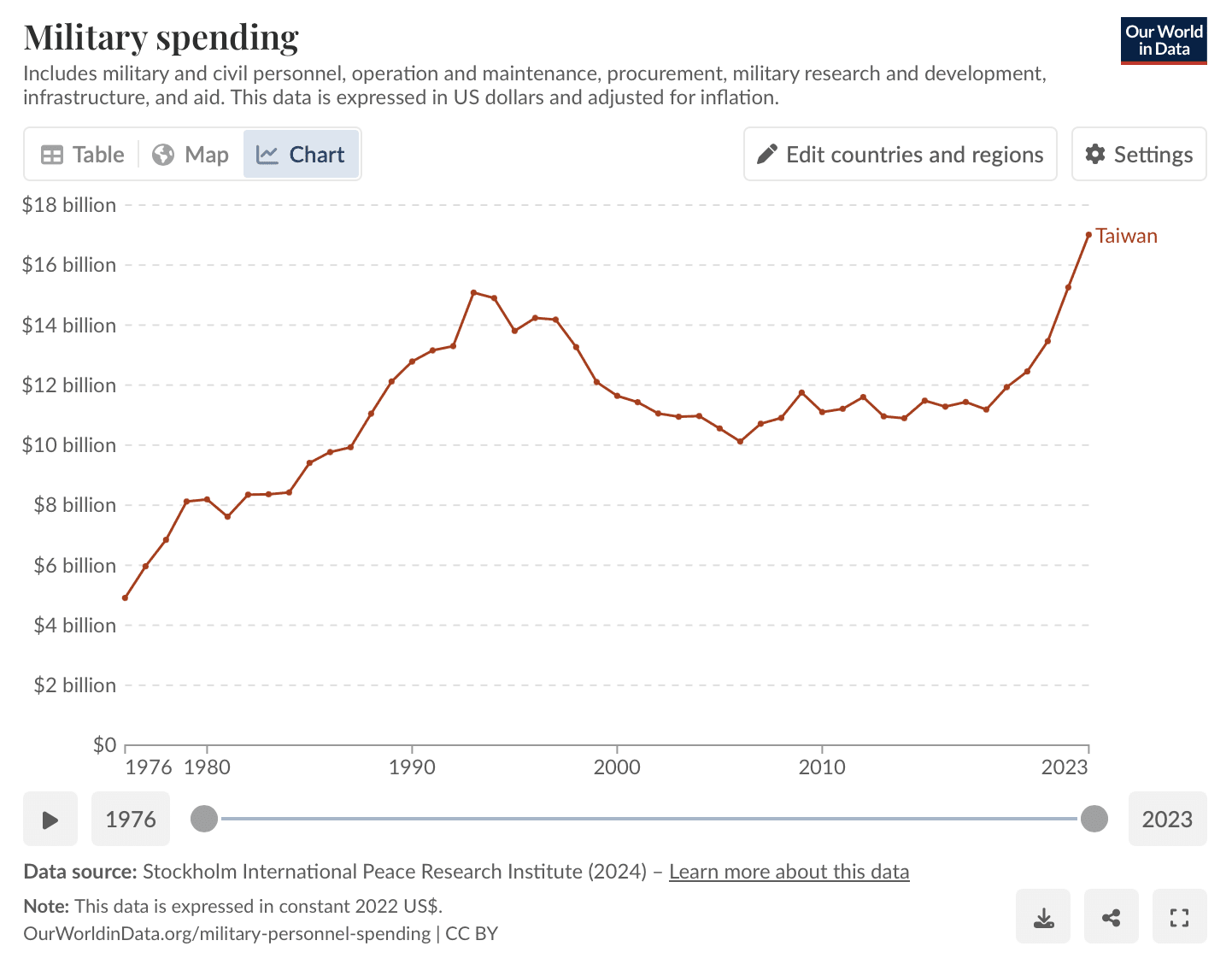

Military spending as a share of Taiwan’s GDP (~2.2%, 2023) is lower than it was during the era when deterrence held (1960s to 1990s, which was also the military dictatorship era). For reference, military spending is 2.8% of GDP in South Korea, 3.4% in the USA, and 3.8% in Poland. In most other western countries the share of military spending is below 2%, so 4.4% is high, but entirely conscionable for a country that faces a clear threat to its existence.

For much of the last 30 years, Taiwan’s military spending has been stagnant in absolute terms (which matters since defensive capabilities are a stock not a flow) despite per capita wealth tripling over the same period.

It would cost ~$17 billion per year to double the defense budget of Taiwan. This is quite a hefty price tag, But it’s only around 1/5th the annual aid provided to Ukraine since the beginning of the war, or 10% what TSMC has pledged to invest in the USA. So mustering such a sum seems possible.

But can this sum be spent effectively?

Toy cost-effectiveness of deterrence

Pulling out the gonkulator suggests that taking the dumb money approach to deterrence and just doubling the defense budget would be about twice as cost-effective at saving lives as the top global health interventions. Keeping all else constant, the reduction in risk would have to be 25% or less to make it less cost-effective than the top global life-saving charity.

As with any such cost-effectiveness analysis of a policy level intervention, this conclusion rests on a scaffolding of assumptions that each independently seem reasonable enough, but all together begin to creak. These assumptions are mainly:

- The catastrophic risks from a Taiwan invasion mentioned in the previous section.

- That a catastrophe implies only a 10% reduction in the population.

- That the lives saved are of equivalent value to those saved in a global health intervention.

- That doubling Taiwan’s military budget would halve the likelihood of invasion, which feels a bit low to me — my intuition sits more around a 67% reduction in likelihood. This is another place where I’d welcome more thoughtful predictions.

Table: Rough cost-effectiveness estimate in lives saved of doubling Taiwan’s military budget

| Parameter | Value | Note |

| Population of Earth 2028 | 8,406,829,000 | OWID, UN |

| Expected deaths from a catastrophe that kills 10% | 13,126,604 | Lower bound b/c only 10%. |

| Decrease in invasion risk if standing military doubled | 50.00% | Guess. |

| Lives saved if Taiwan strength doubled | 6,563,302 | Calculation |

| Cost to increase military budget 2x | $17,000,000,000.00 | 17 billion |

| Cost per life saved with dumb strategy | $2,590.16 | Calculation |

| Value to beat of saving a life | $5,000.00 | ~GiveWell top charity |

| Dumb deterrence money versus best global health intervention | 1.93 | ~2x as c-e. |

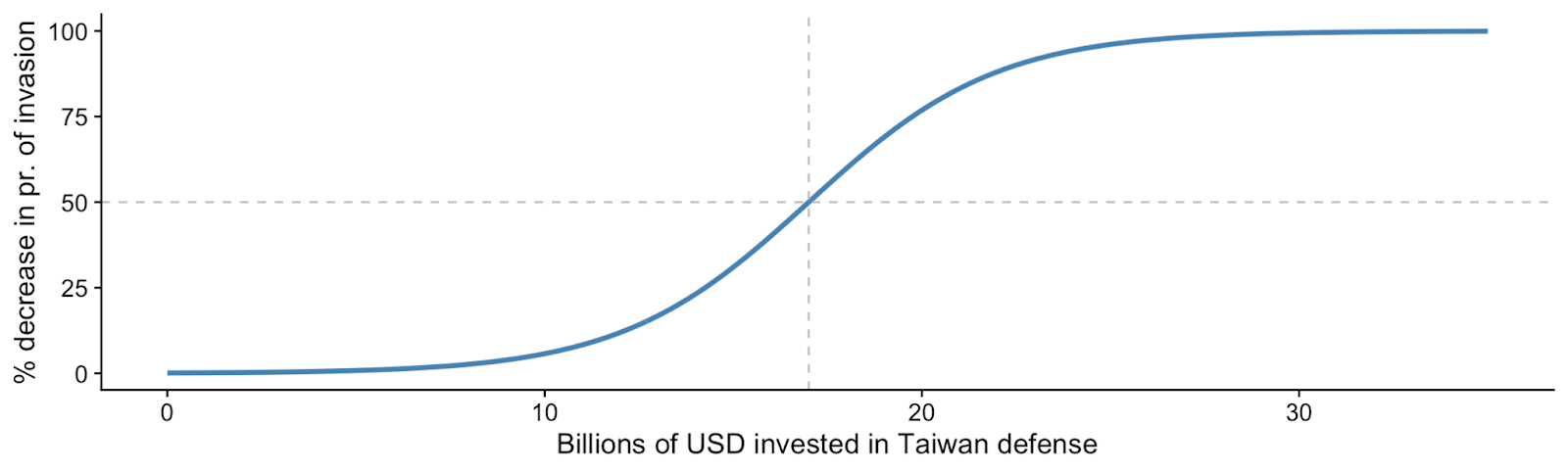

Note that this doesn’t necessarily mean that the marginal dollar contributed to Taiwan’s defense would be this cost-effective. There’s probably a non-linear relationship between investment and deterrence. For example, I can imagine the effect of the first additional billion being less than the 17th — the graph below illustrates this intuition.

Critically, it also seems plausible that an equivalent increase in deterrence from doubling Taiwan’s military budget could be achieved much more cheaply by investing in the right equipment, or by signaling that Taiwan is willing to fight. Most concretely, I think it’s easiest to imagine investments in different platforms that could destroy a Soviet inspired tank or infantry fighting vehicle. Below, I provide some illustrative figures for the “cost per kill” for different platforms (sorry EAs, I know this isn’t what you dreamed of using cost-effectiveness analysis for). I think these are in the right ballpark, but remember that they are only educated guesses.

| Weapon system | Cost | Lifetime tank kill ratio | Cost per tank kill |

| Ukrainian FPV drone | $5,000.00 | 0.02 | $250,000.00 |

| NLAW | $50,000.00 | 0.10 | $500,000.00 |

| M1 Abrams | $10,000,000.00 | 4.00 | $2,500,000.00 |

The final caveat is that I'm oversimplifying by implying that deterrence is equal to the sum of the lethality of a military’s platforms. Of course, the reality is way more complicated than that (C.f., Napoleon on morale as illustrated by Israel in the 1948 war, Vietnam in its Chinese or American wars, the Taliban and Mujahideen, etc). But these estimates are a place to start.

How to cost-effectively increase deterrence

Just about every article on the topic of deterring a cross-strait invasion (1, 2, 3, 4) emphasizes that Taiwan should invest more in relatively cheaper weapons systems that favor the defending side, such as drones, anti-ship and air missiles, and mines. However, I haven’t seen any article that approaches this topic systematically. It would be possible (although far from easy) to use data from the Ukraine war to estimate the return on investment for many different weapon systems, and then reallocate resources to prioritize the most valuable platforms.

But even with the most advanced weapons systems, if the PRC thinks that Taiwan's military will melt away at the first sign of danger, they’re probably going to roll the iron dice.

Taiwan’s military reserves are the clearest illustration of the point. At 1.6 million, comparable to China’s active ground forces and about 10 times the size of Taiwan’s active forces, the reserves alone should be enough to close the conversation about an invasion. That is, if it were certain they could be mobilized and reasonably effective. If this were the case, the PRC would need a force of at least 5 million to take Taiwan. The problem is, the quality of Taiwan’s reserves are uncertain — most analyses I’ve read exclude them from consideration. One commentary claims they only have enough stockpiles of small arms to support 10-20k reservists. My guess is that PRC also dismisses the reserves.

But there should be some way to increase the credibility of these reserve forces. To understand this better, I would try and study some cases of reserves that seem well respected and clearly add to a country's deterrence. These include Finland and Israel, where large and well trained reserves have likely dampened aggression from neighbors (in the case of Finland and the USSR) or helped avert defeat (Israel in the Yom Kippur war).

In 2024, Taiwan increased the period of conscription from 4 months to a year. Meanwhile, South Korea’s conscription period is two years by comparison.

Now, if Taiwan’s reserves are actually respectable, the question becomes how to convey this new reality.

Risks of a deterrence strategy

The PRC has little reason to fear a revanchist Taiwan. There is no Chiang Kai-shek chomping at the bit to invade the mainland (as was the case throughout the early cold war).

However, I think Chris Blattman is right that if deterrence fails, a stronger Taiwan means a longer, bloodier war because there would be a smaller gap between capabilities[16].

In general, increasing deterrence isn’t riskless. High defense investments could be seen as a sign that Taiwan is preparing to declare independence. But I think these fears could be allayed — note that higher defense spending by Taiwan didn’t trigger crises in the past.

3.3. What can be done?

I’ve already laid out some clear diplomatic and military objectives that Taiwan and its partners can pursue. But how do we get there?

I’d like to outline some ideas for funding opportunities to increase military deterrence, since that’s a topic I have a slightly better grasp of, but I would guess there are some clearly good diplomatic initiatives that could be encouraged as well (such as discouraging US politicians from making pointlessly provocative visits to Taiwan).

How tractable is it to increase deterrence?

Over the past decade there has been a surge of attention in US think tanks towards Taiwan’s defense — and Taiwan’s defense posture has changed. It’s worth further inquiry to see what if any causal link there is between the two.

There are some signs of Taiwan moving in the right direction on defense, but it seems like they could really use some more encouragement. There has been…

- Increases in the defense budget, potentially to 3%. But the KMT has also threatened cuts to the military budget.

- Taiwan is investing more in asymmetric capabilities, but still spends a lot on expensive vulnerable platforms (such as warships).

- An increase in the length of conscription, however active troop numbers declined from 160k in 2021 to 150k in 2024.

I lean towards these signs of progress being a signal that things can be pushed even further.

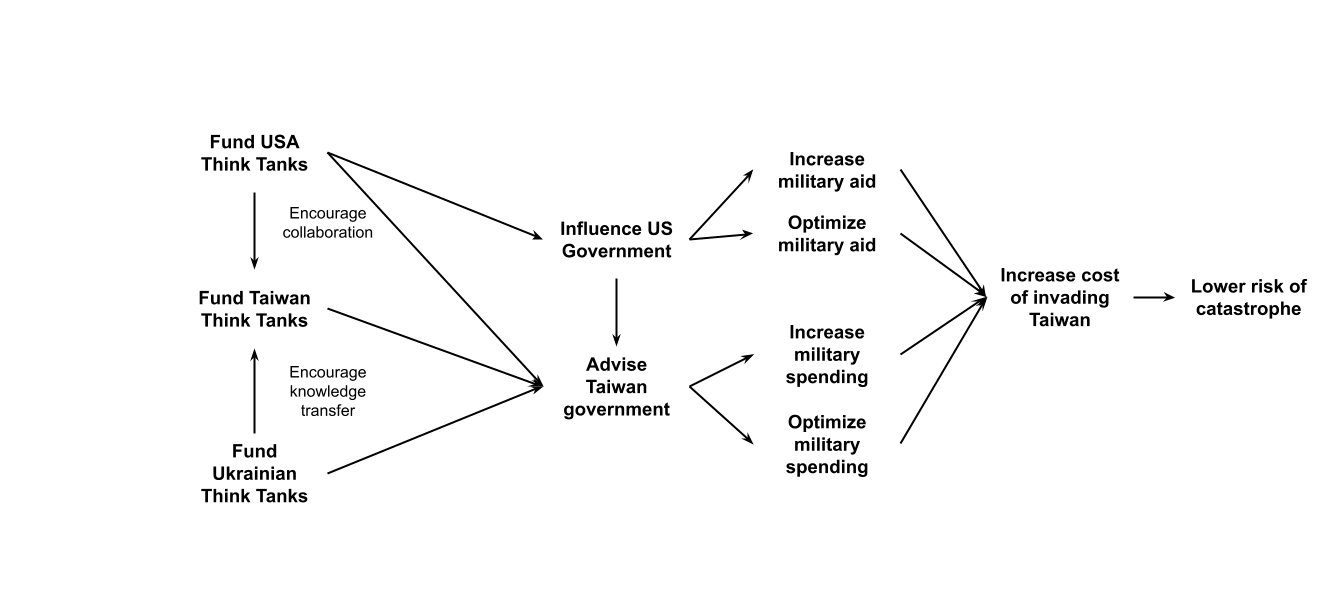

A theory of change for philanthropy increasing Taiwan’s military deterrence

Below I sketch a theory of change, which I follow by trying to articulate specific actionable interventions.

Think tanks could pursue some high-impact research, including:

- Estimating the cost-effectiveness of different weapons platforms to crystalize procurement or military aid priorities. If this already exists I would love to see it.

- Investigating historical case studies where a country has deterred conflict by signalling willingness to fight and mobilizing conscripts, and figuring out what lessons from these examples could apply to Taiwan.

- Test deterrence messaging: Review or run behavioral experiments, surveys, or wargames to identify which signals—like conscription, drills, or elite rhetoric—most effectively increase perceived willingness to fight.

The area that is probably least explored is looking for ways to signal Taiwanese willingness to fight. It seems that a large reason Russia invaded Ukraine was a belief that the Ukrainian army would vanish like the divisions of American-equipped Iraqis meant to defend Mosul from ISIS. But it didn’t, and maybe that outcome should have been more apparent. Taiwanese willingness to fight appears comparable to Ukraine’s before the war (44-48% of Taiwanese report being “very willing” to fight to defend Taiwan, compared to 50.2% of Ukrainians who said they “will resist” if Russia invades). But gauging willingness to fight is notoriously difficult (see also the unexpected Afghanistan collapse).

Clearly, there are limits to what one can do to penetrate the information bubble of an autocrat — but there surely have to be some credible signals one can undertake to convey a country’s willingness to fight. For example:

- Taiwan could hold exercises mobilizing its reserves — this would be economically costly, but could make opportunistic sense in response to a natural disaster),

- Someone could create some popular media that depicts Taiwan resisting (A Formosan “Red Dawn”),

- Heck, I would settle for some beefy macho military ads like those from Russia before the war that clearly made many Americans think Russia was an unstoppable testosterone infused juggernaut.

There are also advocacy or coordination opportunities:

- Advocating that the US DoD and its affiliate contractors get through their massive backlog of weapon supplies to Taiwan

- Encourage lesson sharing across countries. It seems plausible that a lot of US think tanks are primarily speaking to a US audience. Is there anything that could be done with facilitating US and Taiwan dialogue? Or perhaps even more cost-effectively, could we fund workshops that put Ukrainian and Taiwanese military professionals in the same room to discuss topics such as cost-effectiveness and priorities for deterrence?

4. Conclusion and further work

An invasion of Taiwan would be bad. It could be one of the worst things to occur this century. It could trigger a series of events that could be the worst thing to ever happen to humanity.

I’m not sure if anyone is exploring ways to prevent this in the Effective Altruist community. I hope I’m wrong (I’ve been less connected to the EA community in the past few years).

I understand it's a tough challenge. But preventing AI or biological catastrophes is really tough too — and that hasn’t stopped the community from dedicating the better part of its talent and resources to tackling those problems.

The obvious concern here is solvability. I expect that to be where I get the most disagreement. And fair enough, I agree the situation for solvability is similar to the conclusion in Clare’s problem profile: preventing war is not very neglected, and that is also true for averting a war over Taiwan. But unlike the general problem area, which tackles great power conflict at a high level, the particular paths to prevention seem relatively clearer. Instead of relatively vague projects like:

- “Developing expertise in the riskiest bilateral relationships, Learning how to manage international crises quickly and effectively and ensuring the systems to do so are properly maintained

- Doing research to improve particularly important foreign policies, like strategies for sanctions and deterrence

- Improving how nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction are governed at the international level

- Improving how such weapons are controlled at the national level,”

we have slightly less vague interventions, like, “Figure out the most cost-effective weapons platforms for Taiwan to acquire and advocate that the USA delivers them, or Taiwan acquires them.” Now, you may not see this as much of an improvement, but the point is that it seems like there are potentially opportunities worth funding here, and someone (??) should try and see if they exist.

With more time

- Look at case studies of Think Tanks influencing arms procurement policy in other countries.

- Read about wargames and wargame the Taiwan scenario, with an eye towards getting a better intuition for the potential dynamics that would:

- Lead towards a conflict touching the territory of the PRC / USA.

- The conflicting spiraling towards the use of nuclear / other hitherto undeveloped WMDs.

- The relationship between the two of these.

- I’d write more forecasting questions and nag the Samotsvety/Sentinel folks to contribute.

- If Taiwan is invaded, what is the chance of ….

- WW3?

- Nuclear war?

- A biological catastrophe?

- An AI catastrophe?

- Likelihood of China's first strike on USA?

- Conditional likelihood of another Russo Ukrainian conflict

- Conditional likelihood of Russian-NATO conflict

Bonus thoughts

During the course of writing this I collected a few miscellaneous thoughts that may be worth sharing.

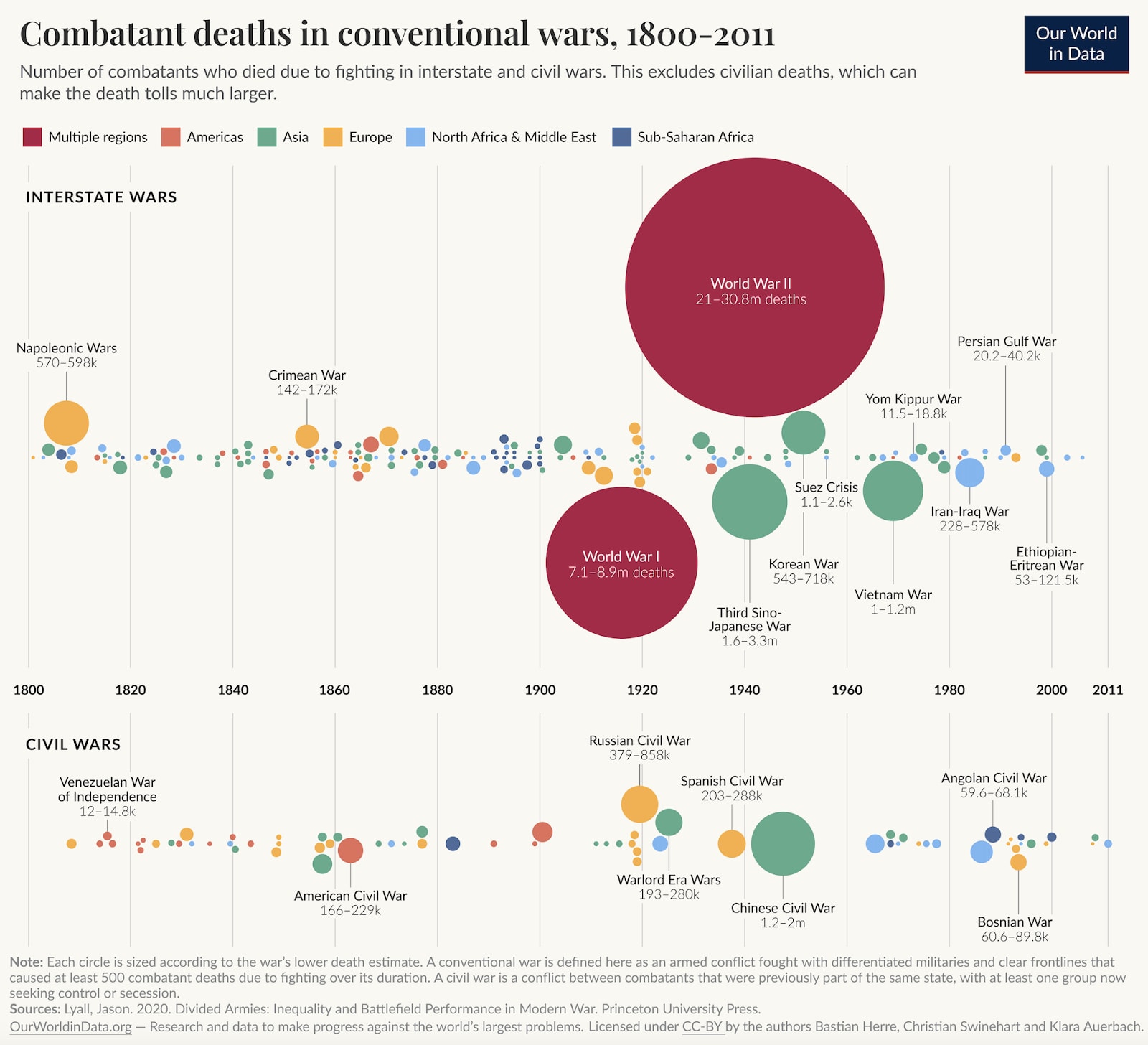

1. Reminder: a catastrophe killing 10% or more of humanity is pretty unprecedented

A lot of bad things have happened in humanity’s history. But few of them have managed to kill more than 10% of the population. This is just referring to modern humans (Homo sapiens), if we expand the reference to other species of Homo, then at least ~5 others have gone extinct – maybe due to climate related reasons. I also know there have also been other supposed bottlenecks for earlier humans (e.g., Hu et al., 2023 estimates a near extinction event 900,000 to 800,000 years ago).

| Reference year | Catastrophe | Death share | World Population (mil) | Deaths (mil) | Source |

| ~72,000 BCE | Mt Toba eruption | Up to 90% (contested) | 0.09 | 0.045 | Wikipedia |

| 1300 | Black Death | 10.96% | 456 | 50 | OWID |

| 1500 | Columbian "exchange" | 9.54% | 503 | 48 | OWID |

| 1206-1227 | Mongol conquest | 9.50% | 445 | 42 | Luke Muelhauser |

| 1919 | Spanish flu | 3.89% | 1,930 | 75 | OWID |

| 1940 | WW2 | 1.27% | 2,330 | 29.5 | OWID |

2. Where’s the Effective Altruist think tank for preventing global conflict?

We EAs love starting a think tank to solve a problem. There are plenty of projects dedicated to reducing AI related risks and bio-risk, but there seems to be few if anyone working on reducing the likelihood of global conflict. I assume this is because someone thought it seems intractable or that EAs don’t have much to contribute. If it’s the former, then have we really given it a good look before giving up? In either case, I suspect that applying a cost-effectiveness mindset to a topic such as conflict prevention is still basically underrated.

I think this topic could potentially be an EA blindspot because of our disproportionate representation in technical fields (as opposed to IR / Poli Sci), and our liberal leaning probably puts most of us on the dovish side of things – although I expect like me, many of you have had some soul searching since 2022. But I wonder. If EA somehow sprung out of Georgetown instead of Oxford – would preventing a war over Taiwan be the top cause?

3. Does forecasting risks based on scenarios change our view on the likelihood of catastrophe?

It seems plausible that the level of aggregation of forecasts affects the estimates. I imagine if you just squint and imagine the risk of catastrophe you may come up with a number like 10%. Then you break it down into risks from AI, bio, nuclear and then you realize you think that each independently feels like it has a 5% risk. Aggregating you’re now at 15%.

But zooming into a particular topic, say nuclear, maybe once you think of it in terms of every possible dyad, you think there’s a 2% chance for each of the scariest ones (NATO-Russia, USA-China, Pakistan-India) and a 1% chance for other pairings (USA-NK, USA-Iran, China-India), assuming independence – you’re now at 9% for nuclear and 19% in total. Imagine the same thing but zooming into a specific dyad and breaking it down by scenario, say for USA and China you’ve got the following (independent) scenarios:

- Taiwan in next 10 years: 0.9%

- Accidental reasons until 2100: 0.5%

- Taiwan from 2035-2100: 0.3%

- South China Sea conflict: 0.2%

- Unforeseen scenario: 0.2%

- Trade war gets kinetic: 0.15%

- Korean war: 0.1%

But this adds up to 2.25%! At this point I think you can see where I’m going. On one hand I think that focusing on particular scenarios probably leads to some availability or other cognitive biases. For example the unpacking effect suggests that people will assign higher probabilities to more detailed scenarios (Rottenstreich and Tversky, 1997; Van Boven and Epley, 2003). But in general the way to make good Fermi estimates is to start granular and work your way up. There appears to be a tension between:

- Top-down forecasting starts with base rates and broad intuition (risks undercounting).

- Bottom-up forecasting builds detailed causal models (risks double counting).

I’m not quite sure what to do about this other than try and integrate both approaches.

- ^

The KMT is one of the two main political parties in Taiwan, and is ironically more in favor of good relations with the mainland.

- ^

This is due to Taiwan’s place in the first island chain, a cold war strategy for how the USA could threaten sino-soviet access to the sea.

- ^

From Jared McKinney on ChinaTalk “In Deng Xiaoping’s 1984 “One Country, Two Systems” speech, he says, ‘It could take 100 years or it could take a thousand years, but peaceful unification is the way forward for Taiwan.’ A thousand-year timeline gives the Communist Party a lot of time to act with restraint — but that’s gone now. The PRC’s third historical resolution from 2021 changed that timeframe to 100 years, starting from 1949.” Blanchett et al. (2023) agrees that “At the highest level of the Chinese Party-state, statements tying national unification with national revival and rejuvenation have been a mainstay of political discourse since the Deng Xiaoping era.12 Such a framing offers an implicit deadline for PRC absorption of Taiwan by 2049.”

- ^

Also, see here.

- ^

For the former, I am thinking of the United States during and after WW1, and for the latter I am thinking of the UK after WW2.

- ^

Note, I’ve heard about but haven’t looked into the DoD memo that signals a focus on deterring China. This would be something to digest with more time. While there’s some China Hawks in the administration, I wouldn’t bet on them winning against the isolationists – but I also don’t trust my judgments on political forecasts.

- ^

Mao, infamously, might have been the only world leader mad enough to reject the horror of mutually assured destruction.

- ^

I think I tend to disagree with others on this. Other Metaculus forecasters (n = 147) believe that the likelihood that China will attack the US if the US intervenes in a Taiwan conflict is 70% (I have it at 40%). I think the community probably believes that the temptation for China to preemptively strike the USA is too high.

- ^

The potential military value of employing nuclear warheads here is much more questionable than the other cases.

- ^

- ^

China is surrounded by neighbors it has fought wars with in the last century (Russia, India, Vietnam, Japan, South Korea). Even if it thinks the likelihood of conflict with any of these is low, its regional environment doesn’t allow it the same strategic nonchalance that has afforded the USA its ability (if not tendency) to focus on a particular strategic issue. Also, I’ll admit this intuition comes from playing strategy games.

- ^

We can imagine other weightings than 50/50 but this is outside the scope of this report, and I’d be very surprised if the appropriate weighting differed considerably from average (30/70 or 70/30).

- ^

I basically imagine that coordination would stop for 25 of the ensuing 75 years until 2100.

- ^

This is consistent with China’s increasing penalization of advocating for independence (the supreme court making it permissible to imprison someone for life or launching an online portal that allows you to report people for speaking about independence).Warnings against independence seem like they’ve become more common. I think some of this shift is because the DPP, which is more sympathetic to independence, has won the last three presidential elections. Much of the anti-independence rhetoric seems targeted at the DPP.

- ^

Compare reactions to Russia's invasion of Ukraine to Azerbaijan’s invasion of Armenian territory that was internationally recognized as Azerbaijani. Other countries are far less likely to interfere in what is seen as an internal affair.

- ^

There may also be a repugnant silver lining to a longer war. An uncontested invasion means that China could potentially expropriate TSMC mostly intact. Plausibly becoming the world leader in semiconductor manufacturing. The more contested the invasion, the likelier that PRC’s semiconductor manufacturing is set back for a decade, potentially giving the west breathing room to safely develop AGI (see Jordan Schneider EA forum post, comment on Matt Barnett’s EA forum post). This seems like a strange thing to hope for though.

I remember hearing from my dad who served in the ROC army some time around the 1970s that conscription used to be two years of service. According to Wikipedia this got reduced because they were trying to switch to an all-volunteer force in the 2010s and only restored due to fears that an invasion was becoming imminent recently.