As the farmed animal advocacy movement expands globally, a strategic question emerges:

Should we prioritize preventing or slowing the spread of industrial animal agriculture in future high-production regions (e.g. parts of Sub-Saharan Africa) over investing in advocacy in currently high-production regions that remain neglected in terms of farmed animal advocacy (e.g. parts of Asia and Latin America)[1]?

Some important notes

- In this post, to prioritize X over Y means preferring to direct new funding and talent towards X rather than Y.

- All of these regions—future high-growth and current high-production areas in Africa, Asia, and Latin America—are underfunded relative to the number of animals affected and the scale of advocacy challenges they face. Ideally, they would all receive significantly more funding and attention. The purpose of this debate is not to pit neglected regions against each other, but to explore which might be most impactful for marginal resources.

- The following points are generalizations that don’t necessarily capture the full diversity of contexts within each region, and there will be exceptions. For example, in many LMICs in Sub-Saharan Africa, animal agriculture is generally less entrenched, whereas in Asia and Latin America it tends to be more established—though this is by no means a hard rule.

Why I’m writing this

My intention with this post is to provide a few preliminary pointers to spark discussion, rather than to present a comprehensive set of arguments and data. If you have additional evidence, perspectives, or counterarguments, please share them in the comments.

I’m writing from my perspective as @Hive's Asia Ambassador. At Hive, we provide a platform for nuanced, impact-focused discussions about strategy in the farmed animal advocacy movement, and we think this debate could benefit from a wide range of perspectives. If you’d like to continue the conversation beyond the Forum, you can join the Hive Slack, where many advocates explore these questions in more depth. We’re curious how others in the movement are thinking about these strategic regional decisions—especially if you work in or with these areas.

Background

This debate is inspired by research exploring interventions that might be effective in combating the rise of factory farms in Sub-Saharan Africa, e.g. this report by Bryant Research and @AnimalAdvocacyAfrica. (Interested readers could also refer to Animal Advocacy Africa's various reports, and @Animal Ask's reports on Egypt, Ghana, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.)

According to a previous post by Animal Advocacy Africa:

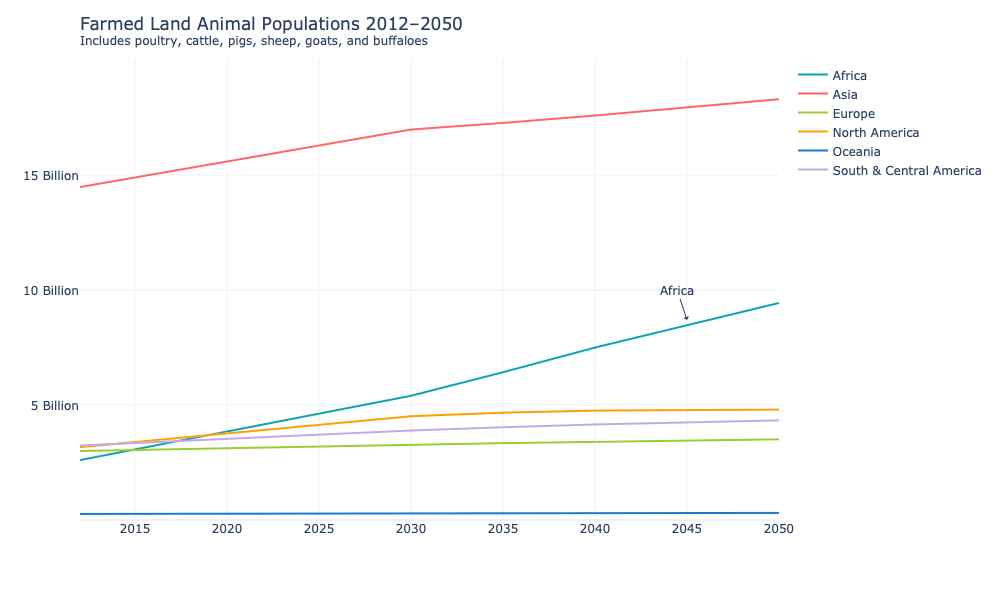

At present, Asia leads and will continue to lead all continents in terms of the total number of farmed land animals. This can largely be attributed to factory farming in China, Indonesia, and India. Nevertheless, Africa’s livestock numbers are expected to increase by a much larger absolute number and at a higher rate than Asia’s projected 26% rise from 2012 to 2050. [Emphasis in original.]

At the same time, Asia and Latin America are among the top regions driving global farmed animal production. Asia alone is responsible for the vast majority of land animals slaughtered for meat each year[2], and it also leads aquaculture production by a wide margin[3]. Latin America is the second-largest contributor to global aquaculture[4]. While industrial animal agriculture is more entrenched in these regions, advocacy remains underfunded relative to the scale of animal suffering.

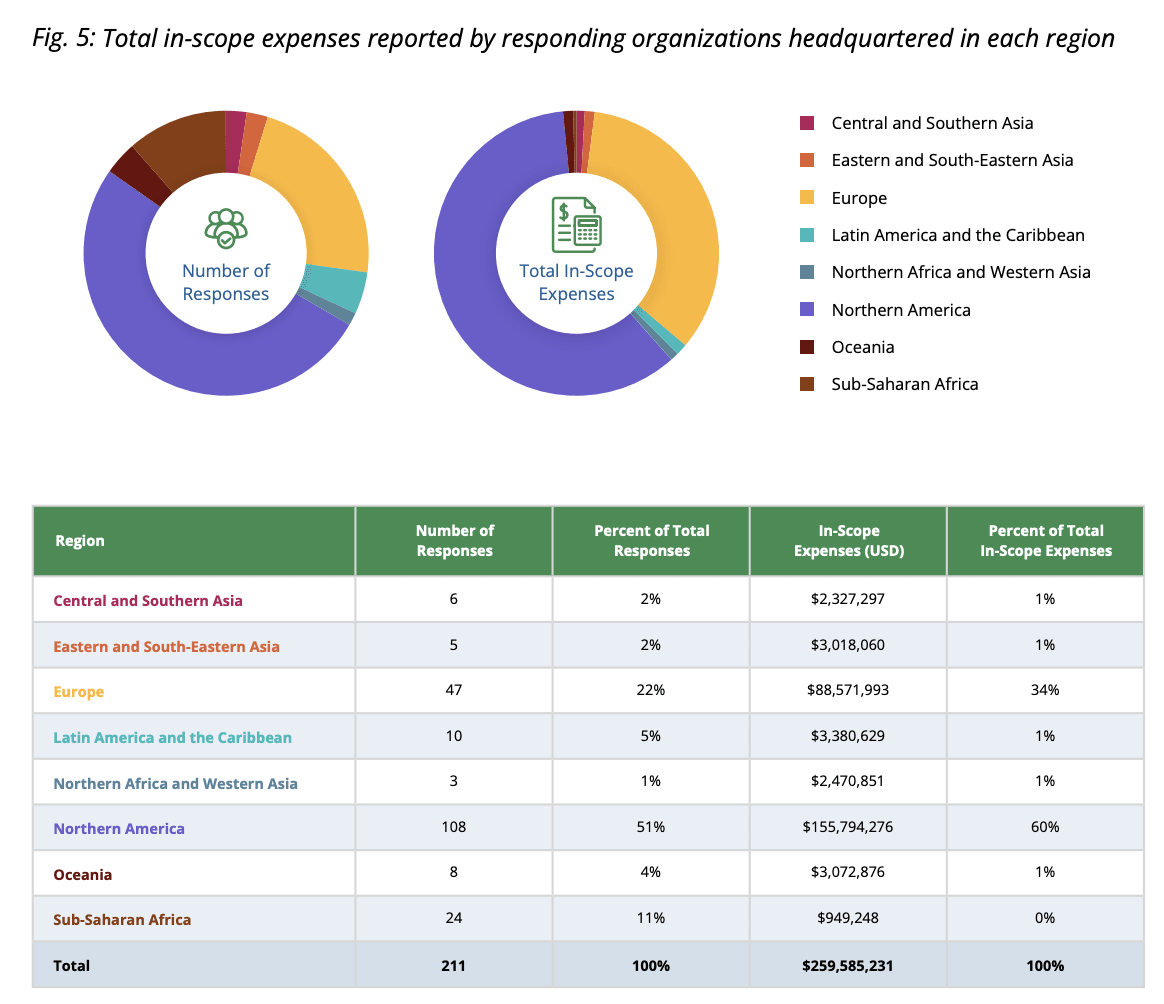

For example, the Stray Dog Institute’s 2024 State of the Movement report shows organizations from Africa, Asia, and Latin America contributed only around 6% of the total in-scope expenses[5] tracked by its survey–with those from Sub-Saharan Africa contributing the least.

Arguments for preventing or slowing industrial animal agriculture in future high-production regions

- Prevention may be more effective than reversal: It seems easier to prevent a system from becoming established than to dismantle it after it has taken root. In regions where industrial animal agriculture hasn't yet become the dominant model, there may be opportunities to promote alternative food systems, influence policy development, and shape consumer preferences before powerful industry interests become entrenched.

- Influencing growth trajectories creates compounding benefits: Small advocacy wins early in a region's development can significantly alter growth trajectories, potentially preventing decades of animal suffering through compounding effects. Early-stage interventions may have outsized long-term impacts.

Arguments for investing in advocacy in currently high-production regions that remain neglected in terms of farmed animal advocacy

- Established systems may be more vulnerable to change: Perhaps counterintuitively, it might be easier to reform or replace industrial animal agriculture once it's established rather than prevent its emergence. In regions where factory farming is already widespread, there may be more documented evidence of its negative impacts on animal welfare, public health, the environment, and local communities—providing advocates with powerful arguments for change.

- Relatedly, industrialization creates more structured advocacy targets: As animal agriculture industrializes, it typically consolidates into fewer, larger, and more structured corporate entities. These companies are often more sensitive to consumer pressure, regulatory changes, and reputational damage than numerous small-scale producers. Having clear targets for corporate campaigns and policy advocacy can make strategic interventions more feasible and impactful.

- Building on movement experience: The farmed animal advocacy movement has developed significant expertise and experience working within contexts where industrial animal agriculture is already established. Our more successful campaigns and interventions come from these contexts. Leveraging this existing knowledge base in similar high-production regions might yield more reliable results than pioneering entirely new approaches in pre-/near-industrial contexts.

- Intensification may be driven by powerful economic forces: It might not be feasible to significantly alter the trajectory of intensification because of various driving forces (economic, demographic, political, etc). Rising incomes, urbanization, and population growth create strong market incentives for industrial animal agriculture. If preventing intensification is unlikely to succeed, resources might be better directed toward mitigating harm in regions where industrial systems are already operating at scale.

- Uncertainty about future trajectories: It is not necessarily guaranteed that industrialization will follow the same path in all regions. Some areas might develop hybrid systems or leapfrog directly to more sustainable alternatives due to unique economic, cultural, or environmental factors. This uncertainty makes it difficult to predict where preventative efforts would have the greatest impact.

This is a complex topic, and as farmed animal advocates, we have so much to learn and have lots of uncertainty. If you've read this post in full and would like to contribute to the discussion, but are worried that you don't have much to contribute, please err towards contributing. Myself and the team at @Hive would be grateful for it. Thank you for reading!

Thanks to Sofia Balderson, Thomas Billington, Megan Jamer, Haven King-Nobles, Björn Ólafsson, Moritz Stumpe, Toby Tremlett, and Kevin Xia for reviewing a draft version of this post. Their feedback was invaluable, and this post doesn’t necessarily reflect their views. All mistakes are my own.

- ^

In this post, I use this definition of various regions.

- ^

Our World in Data. Land animals slaughtered for meat, 1961 to 2023.

- ^

Our World in Data. Aquaculture production.

- ^

Our World in Data. Aquaculture production.

- ^

In-scope expenses are defined in the report as the portion of an organization’s expenses going to work that directly or indirectly benefits animals farmed or caught for food.

I’m glad to see this debate happening. I believe there’s a uniquely high-leverage window to act now before industrial animal agriculture fully entrenches itself in Africa. One major example: the $2.5 billion expansion of JBS into Nigeria, which is projected to slaughter 150–200 million chickens, cattle, and pigs annually. Moves like this could rapidly transform local food systems toward intensive industrial models, making future reforms much harder and more expensive. I also see other African countries in the early stages of industrial growth.

Compared to Asia/Latin America, Africa has far fewer advocacy organizations as well as advocates and minimal corporate lobbying power from animal welfare groups. That means our potential interventions now could help set higher standards for farmed animals or even slow harmful industry practices before they become the norm.

I’m curious: Are there cost-effectiveness studies comparing prevention in Africa with reform in other (entrenched) regions? I think this could help funders make more informed strategic decisions.

Thanks for sharing this example, Asampana. Do you have a rough idea of what it would take to prevent this expansion, i.e., at what level does the relevant decision-making power lie? And are there existing political movements or currents that are conducive to success?

I once heard a talk by @Daniela Waldhorn that raised the thought experiment of "what if animal advocates had established a movement against factory farming when it was still in its infancy?" There may be something to the case that a large number of people could be mobilized to support such bans and that opposition to them is surmountable when the industry is still young. But it still seems likely that JBS would seek to expand elsewhere instead.

Thank you, Squeezy! I think you raised a really important question about where decision-making power lies and whether movements can mobilize around factory farming in its infancy.

I’m glad to say that, there has already been structural work on this, my colleagues, Daniel Ayinde and Fasipe Isaac, with support from the @AnimalAdvocacyAfrica training program, are developing a project called Sanuvia, focused on advocating for stronger animal welfare regulations in response to the JBS expansion in Nigeria. Sanuvia reflects exactly the kind of early, coordinated action you described.

This makes me confident that with the right support, Africa could build momentum before factory farming becomes deeply entrenched.

It might be helpful to distinguish between two different strategies:

These are just speculations, perhaps this is a false dichotomy.

Thanks for breaking down the two strategies, Squeezy! I think that framing is very useful.

I agree that animal advocates alone might not have the political leverage, but I see real potential in aligning with adjacent movements and political decision makers. Also, student networks often share overlapping concerns and could become strong allies.

I vote that slowing intensification is a bit more likely to be the best use of resources at current margins. I agree that this probably has lower tractability and that, as @Moritz Stumpe 🔸 says, the African advocacy movement can't effectively absorb as much funding and labour as the Asian movement. But I think there's a very narrow window to slow the takeoff of sub-Saharan factory farming, and we should take the low-probability, high-EV, urgent bet while we can.

That said, I actually think that steering this takeoff, i.e. 'welfare advoacy in future high production regions', is probably a better use of resources than either slowing intensification or 'welfare advocacy in neglected, high production regions'.

It's a great question, Angel, and I strongly think everybody should feel highly uncertain -- I feel very open to changing my mind. I've been researching the intensification of hen farming in sub-Saharan Africa for the past few months, so that informs my answer, but I don't feel as informed about intensification in Latin America, or the intensification of aquaculture.

Thanks Ben. Excited to hear about your research! Please do share that with me/us, as soon as it's ready :)

also eagerly waiting for the research report.

Thank you, Ángel, for opening this debate. I will focus on aquaculture, which I consider the most neglected sector and the one that affects the largest number of sentient beings by individual count. In my view, it is the most illustrative example to frame the problem.

In Latin America, the challenge is not only to confront an already established industry, but also to act preventively against an expanding threat: shrimp farming in new countries across the region. Today, Ecuador is the world’s largest exporter of shrimp and one of its leading producers. In addition, Panama, Mexico, Brazil, Honduras, Guatemala, Colombia, and Cuba are also involved in production. At the same time, countries like Chile (the world’s second-largest salmon producer) are exploring the development of new shrimp farming initiatives through research and pilot programs, although no commercial industry has yet been established. Advocacy in this context is preventive: while general aquaculture frameworks exist, there are no specific welfare standards for shrimp, let alone operational bans.

From my perspective, the dilemma is not “established vs. preventive,” but rather “established + preventive vs. preventive.” Moreover, if we use coastline length as a proxy for aquaculture-suitable coast, Latin America and the Caribbean together account for approximately 72,000 km, compared to Africa’s 40,000 km. This provides an objective measure of the potential scale of the problem if we fail to act in time.

This is compounded by a severe underrepresentation of organizations working beyond companion animals. I speak from direct experience: I am Chilean, and 11 years ago I co-founded the legal organization Fundación Derecho y Defensa Animal, with a strong focus on legal advocacy. Based on that foundation, and through the work of LatinGroup for Animals, we can affirm that in key countries like Chile and Ecuador, there are only three or four professionalized organizations dedicated to legal animal advocacy, and in the Caribbean, there are virtually none. This is a field-based empirical observation that underscores the urgency of a coordinated regional strategy.

Do you have a guess for what % of each coastline is already used for aquaculture?

Africa's coastline measures approximately 30,500 km, while the combined coastline of Latin America and the Caribbean is substantially shorter, at roughly 22,000 km.

Africa's land area is about 30,365,000 km² (11,724,000 sq mi). Latin America and the Caribbean together have a total land area of approximately 20,139,378 km² (7,775,854 sq mi)

So i also think Africa would relatively be a best fit for implementation.

My vote may be surprising for someone working at @AnimalAdvocacyAfrica. So let me explain:

I agree with Moritz's view on this. Africa and African organisations still need to develop the capacity to absorb as much funding. But then again, there is a need to prioritise Africa when you begin to consider how long it takes to get political support and for this political support to materialise into actionable policies. I am of the opinion that starting early is best in the African situation because government laxity is a concern, and they may likely entertain advocacy that helps them to create jobs or develop the economy (which is a major concern, by the way). Talk about the economy is not always at the forefront of animal welfare discourse.

100% agreed on starting early. And then growing the capacity as fast as we can effectively!

Thank you for explaining clearly Moritz, especially the capacity to absorb funding.

From what i have noticed, there are students who have shown interest in animal welfare in some African countries. What’s often missing out is not willingness or talent, but structured support and coordination to help these groups scale effectively

Kudos to Animal Advocacy Africa for already providing this type of foundation and training . I think with time, Africa will get the capacity to absorb more resources

Thanks Maxwell! We're working hard on trying to increase the capacity for the African movement to absorb more of this funding effectively. I hope and think our alumni (like yourself) will play a key part in this!

I support this, I gave an EAGx (Singapore) talk basically arguing for this (maybe a more general point, that we should focus much more on prevention)

40%➔ 60% disagreeI am generally more optimistic about advocacy that seeks to improve welfare conditions than advocacy that tries prevent the expansion of intensive production. Welfare campaigns have smaller asks, which I suspect makes them more tractable. I also worry that obstructed intensification in one place will largely be offset by intensification or production expansion elsewhere.

I would vote differently if the topic were framed in terms of focusing more on places that have growing industries instead of in terms of preventing the spread of intensification. I strongly welcome evidence or speculation that preventing spread is tractable.

The tractability on this will be terrible - you'll be trying to persuade poor countries to limit quality/quantity/variety of food availability to their own people, and you can imagine how that will go. Additionally, there may be potential human costs in terms of nutrition and economic growth.

If you do want to affect AW in LMICs, Innovate Animal Agriculture style work trying to affect the kind of industrial animal agriculture seems far more tractable (in fact it's probably more tractable than in HICs, since e.g. there are no sunk costs in terms of equipment and capital).

There is momentum currently