I was encouraged to post this here, but I don't yet have enough EA forum karma to crosspost directly!

Epistemic status: these are my own opinions on AI risk communication, based primarily on my own instincts on the subject and discussions with people less involved with rationality than myself. Communication is highly subjective and I have not rigorously A/B tested messaging. I am even less confident in the quality of my responses than in the correctness of my critique.

If they turn out to be true, these thoughts can probably be applied to all sorts of communication beyond AI risk.

Lots of work has gone into trying to explain AI risk to laypersons. Overall, I think it's been great, but there's a particular trap that I've seen people fall into a few times. I'd summarize it as simplifying and shortening the text of an argument without enough thought for the information content. It comes in three forms. One is forgetting to adapt concepts for someone with a far inferential distance; another is forgetting to filter for the important information; the third is rewording an argument so much you fail to sound like a human being at all.

I'm going to critique three examples which I think typify these:

Failure to Adapt Concepts

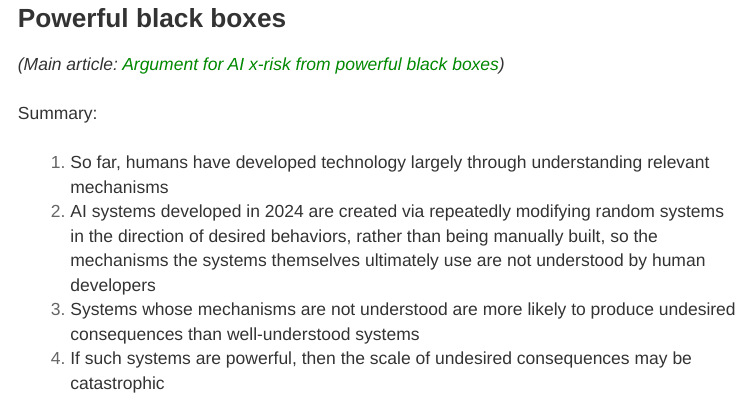

I got this from the summaries of AI risk arguments written by Katja Grace and Nathan Young here. I'm making the assumption that these summaries are supposed to be accessible to laypersons, since most of them seem written that way. This one stands out as not having been optimized on the concept level. This argument was below-aveage effectiveness when tested.

I expect most people's reaction to point 2 would be "I understand all those words individually, but not together". It's a huge dump of conceptual information all at once which successfully points to the concept in the mind of someone who already understands it, but is unlikely to introduce that concept to someone's mind.

Here's an attempt to do better:

- So far, humans have mostly developed technology by understanding the systems which the technology depends on.

- AI systems developed today are instead created by machine learning. This means that the computer learns to produce certain desired outputs, but humans do not tell the system how it should produce the outputs. We often have no idea how or why an AI behaves in the way that it does.

- Since we don't understand how or why an AI works a certain way, it could easily behave in unpredictable and unwanted ways.

- If the AI is powerful, then the consequences of unwanted behaviour could be catastrophic.

And here's Claude's just for fun:

- Up until now, humans have created new technologies by understanding how they work.

- The AI systems made in 2024 are different. Instead of being carefully built piece by piece, they're created by repeatedly tweaking random systems until they do what we want. This means the people who make these AIs don't fully understand how they work on the inside.

- When we use systems that we don't fully understand, we're more likely to run into unexpected problems or side effects.

- If these not-fully-understood AI systems become very powerful, any unexpected problems could potentially be really big and harmful.

I think it gets points 1 and 3 better than me, but 2 and 4 worse. Either way, I think we can improve upon the summary.

Failure to Filter Information

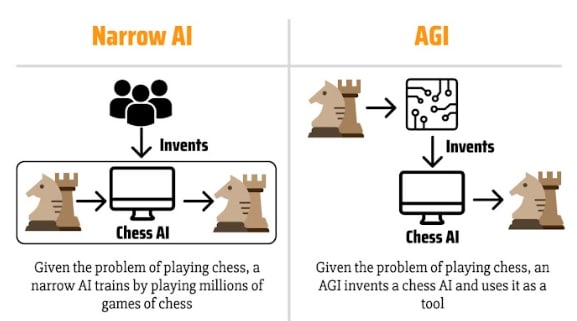

When you condense an argument down, you make it shorter. This is obvious. What is not always as obvious is that this means you have to throw out information to make the core point clearer. Sometimes the information that gets kept is distracting. Here's an example from a poster a friend of mine made for Pause AI:

When I showed this to my partner, they said "This is very confusing, it makes it look like an AGI is an AI which makes a chess AI". Making more AIs is part of what AGI could do, but it's not really the central difference between narrow AI and AGI. The core property of an AGI is being capable at lots of different tasks.

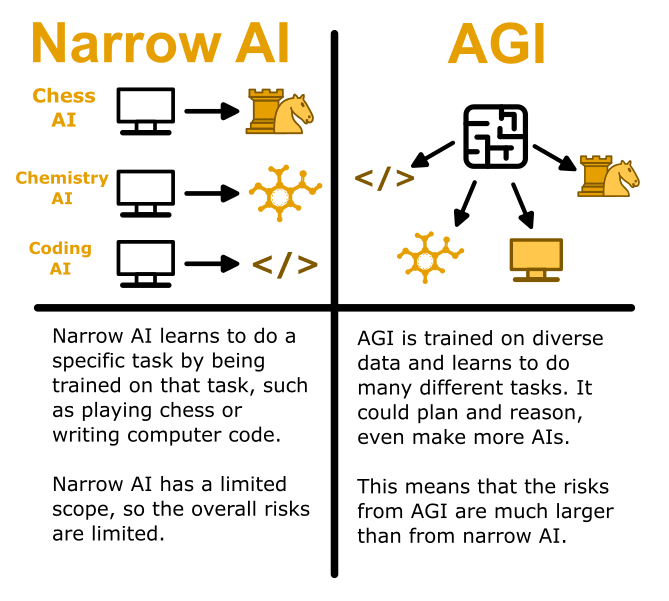

Let's try and do better, though this is difficult to explain:

This one is not my best work, especially on the artistic front. It's a difficult concept to communicate! But I think this fixes the specific issue of information filtering. Narrow AI's do a single, bounded task; AGI can do a broad range of tasks.

Failure to Sound Like a Human Being

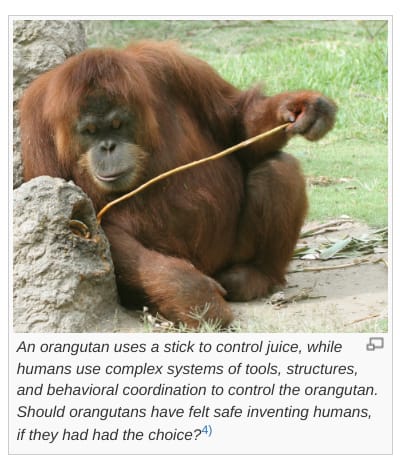

In this case, the writing is so compressed and removed from the original (complicated) concept that it breaks down and needs to be rewritten from the ground up. Here's a quick example from the same page (sorry Katja and Nathan! You're just the easiest example arguments to find, I really really do love the work you're doing). This is from the "Second Species Argument" which was of middling effectiveness, though this is a secondary example and not the core argument.

This is just ... an odd set of sentences. We get both of the previous errors for free here too. "An orangutan uses a stick to control juice" is poor information filtering: why does it matter that an orangutan can use a tool? "Should orangutans have felt save inventing humans" is an unnecessarily abstract question, why not just ask whether orangutans have benefited from the existence of humans or not.

But moreover, the whole thing is one of the strangest passages of text I've ever read! "An orangutan uses a stick to control juice, while humans ... control the orangutan" is a really abstract and uncommon use of the word "control" which makes no sense outside of deep rationalist circles, and also sounds like it was written by aliens. Here's my attempt to do better:

For a start, I'd use a chimp instead of an orangutan, because they're a less weird animal and a closer relative to humans, which better makes our point. I then explain that we're dominant over chimps due to our intelligence, and give examples. Then instead of asking "should chimps have invented humans" I ask "Are chimps better off because a more intelligent species than them exists?" which doesn't introduce a weird hypothetical surrounding chimps inventing humans.

Summary

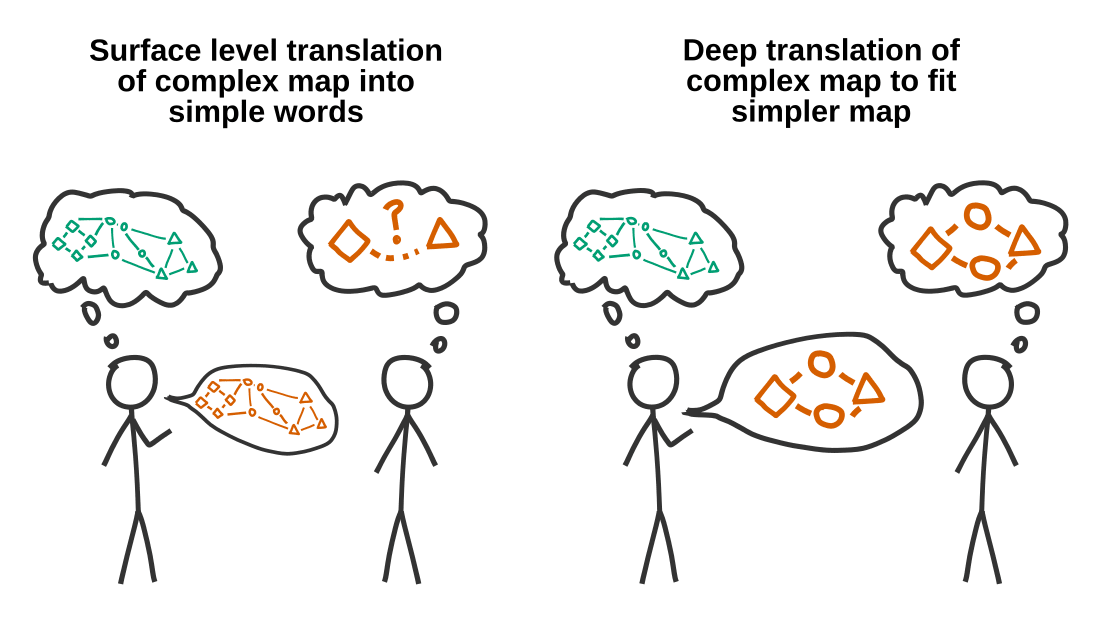

It's tempting to take the full, complicated knowledge structure you (i.e. a person in the 99.99th percentile of time spent thinking about a topic) want to express, and try and map it one-to-one onto a layperson's epistemology. Unfortunately, this isn't generally possible to do when your map of (this part of) the world has more moving parts than theirs. Often, you'll have to first convert your fine-grained models to coarse-grained ones, and filter out extraneous information before you can map the resulting simplified model onto their worldview.

One trick I use is to imagine the response someone would give if I succeeded in explaining the concepts them, and then I asked them to summarize what they've learned back to me. I'm pretending to be my target audience who is passing an ideological turing test of my own views. "What would they say that would convince me they understood me?". Mileage may vary.

Thanks for that fantastic article. Both your written and pictorial explainers are far better than the originals, which quickly helped convince me of your arguments.