What a way to go

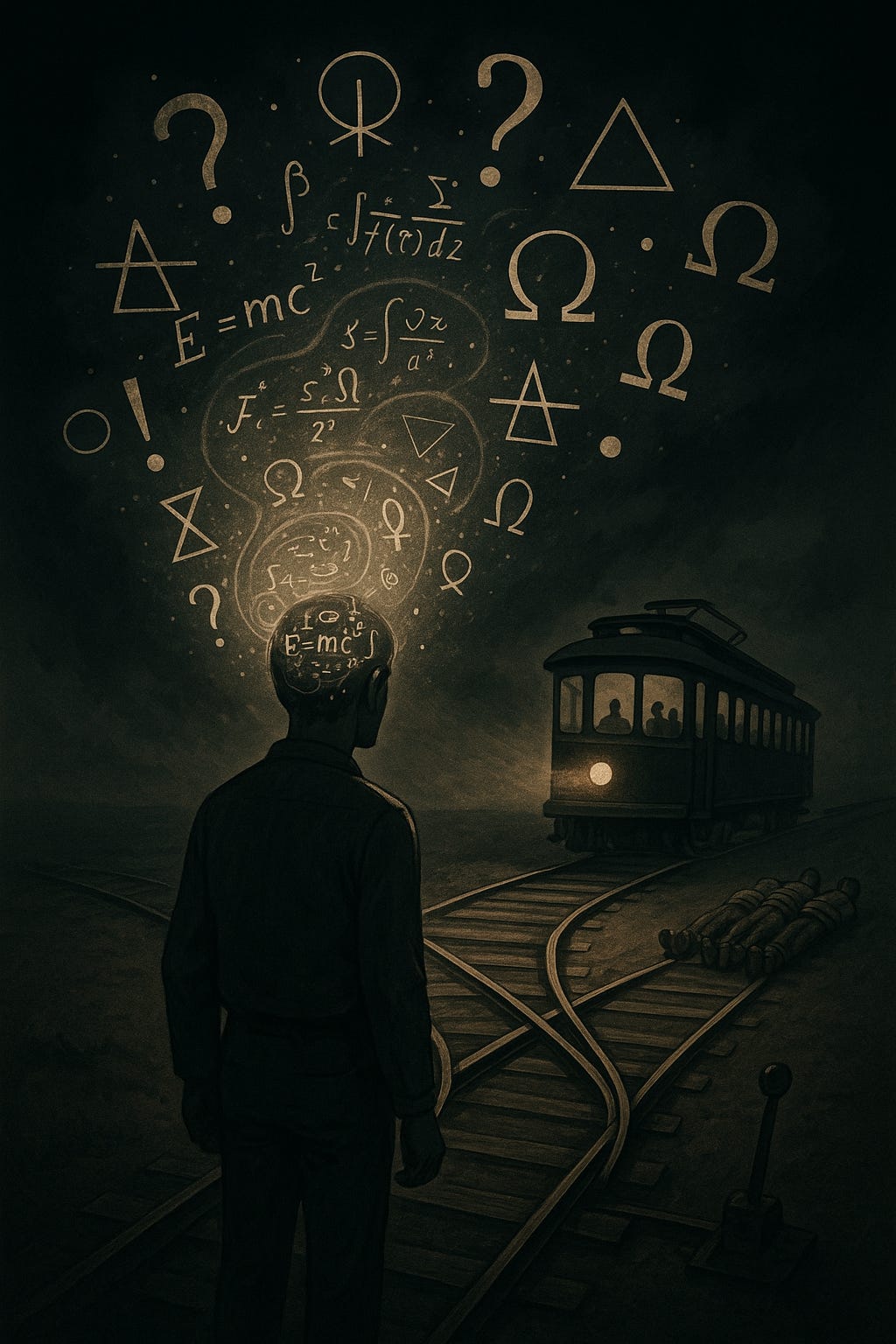

How badly would it suck to die because a person who could have saved your life (along with the lives of four others tied to the train tracks beside you) preferred “allowing” to “doing”? A second was just about to save you when they realized that the side track—where just one person awaited as collateral damage—later loops back, turning the purportedly-collateral damage into an instrumental killing. (“Lemme get this straight,” the escapee scratches his head. “You were OK with killing me when it seemed pointless, but now that my death would actually save the five you’ve suddenly had second thoughts!? Huh. I’m happy to escape this one, but for future reference: if you ever again plan to kill me, at least try to make it so my death serves a valuable purpose, OK?”)

A third agent planned to redirect a bomb onto the (one-person) trolley, until they decided that their action was more accurately described as introducing a new threat into the situation rather than just deflecting an existing threat. After that, your chances ran out and the trolley flattened you. But the trolley was just the proximate cause of your death. The deeper, more annoying reason you died was that (i) those who could have saved you followed deontological guidance, and (ii) that guidance turned on prioritizing abstract metaphysical distinctions over real human lives and well-being.

At Heaven’s pearly gates, you ask St. Peter to send you back to haunt your turncoat would-be rescuers for a few days. You have a simple question for each of them: Why should life or death decisions—and your death, in particular—turn on a question so empty and trivial as mere metaphysical taxonomy? “I can’t believe this!” you harangue the frightened souls. “It’s not like the one you prioritized over all the rest of us was your child or anything. You even wanted to save us at first! But then you changed your mind, and left most of us to die, because of… what, exactly? Words? The precise causal relation between your oh-so-holy agency and the rest of us? Even though your metaphysical update made no difference whatsoever to anything that those of us with lives on the line had any reason to care about? (We care about whether we live or die, not whether we do so as a result of a doing or an allowing, let alone anything yet more abstruse.)[1] What is wrong with you!?”

I think this is an important question. People object to utilitarianism that it doesn’t match well with intuitions about how to use moral language. But such superficial objections are easily dealt with via moves like deontic fictionalism or “two level” distinctions between theoretical criteria and practical decision procedures. The objection to deontology is far deeper: it decides life or death moral questions by reference to clearly irrelevant metaphysical properties that it makes no sense to care about. We can fudge deontic verdicts. But there’s no easy fix for lacking a comprehensible rationale for your moral verdicts. “I just feel compelled to bring about worse outcomes for no reason” is a special kind of crazy. (It sure would be annoying to die because of it.)

A frictionless slope

Here’s a thought experiment that (another professor tells me) convinces many undergrads that the utilitarian verdict in Transplant is more defensible than they initially realized:

Begin by considering two alternative possible worlds. In the first world, five hospital patients die for lack of vital organs, and a passerby goes on to live a happy life. In the second world, the passerby’s head falls off (by brute natural chance) just as he’s walking past the doctor’s surgery. The doctor then uses the man’s organs to save the five patients, who each go on to live happy lives. Further suppose that all else is equal—there are no other relevant differences between the two possible worlds. Which world should you prefer to see realized? Presumably the second.

Now suppose that God lets you choose which of the two worlds to actualize. (After making your decision, the divine encounter will be wiped from your memory.) You get two buttons. If you press the first button, world #1 is realized, and the passerby will live. If you press the second button, world #2 is realized, and the five patients will live instead. Which button should you press? Again, surely the second. All else equal, we should choose to make the world a better place rather than a worse one. (You’re not killing anyone: just realizing a world in which, among other things, a fortuitous freak accident will occur.)

Let’s elaborate on how it is that the passerby’s head happens to fall off (in the second world). It turns out an invisibly thin razor-sharp wire was blown into place by a freak wind which fixed its position at neck height where the man was walking past. (No-one else was hurt and the wire soon untangled itself and blew away harmlessly into the nearest dumpster.) This presumably will not alter the moral status of any of our above judgments.

Now suppose that, instead of two buttons, God gives you a length of razor-sharp wire with which you can make your decision. By putting it straight in the dumpster, you will realize world #1. By fixing it in the appropriate place, you will realize world #2. Again, your memories are subsequently wiped. What should you do? The situation seems morally equivalent to the previous one. There don’t seem any relevant grounds for changing your choice.[2] Thus the right thing to do, in this bizarrely contrived scenario, is to kill the passerby to save five.

Far from being any kind of “bullet” to bite, when the Transplant case is suitably elucidated, the life-saving verdict is arguably quite plain to common sense.

(Why, then, shouldn’t doctors go around killing people? Presumably because it wouldn’t have good expected consequences in real life! There are good utilitarian reasons to set up laws, norms, and institutions that prevent people from engaging in naive instrumentalist reasoning. Why anyone believes this to constitute an objection to utilitarian theory is one of the great mysteries of contemporary sociology of philosophy.)

- ^

See also Avram Hiller on the patient-centered perspective in moral theorizing.

- ^

Someone could brutely insist that the fact that you’re now killing the victim makes all the difference. But this detail of implementation seems too far removed from all that substantively matters, as was already in the previous scenario. Why should an agential fixing of the wire make such a difference compared to an agent’s choosing to realize the world in which a freak wind so affixes the wire? Whatever moral concern you have for the six people in the situation whose lives are on the line should be just the same across both scenarios. Everything is exactly the same as far as all six potential victims are concerned.

Executive summary: The post argues that deontological moral theories dangerously misprioritize abstract metaphysical distinctions—such as doing vs. allowing or agential causation—over real human lives, and that properly framed utilitarian reasoning leads to more defensible and humane decisions in life-and-death cases.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.