Today, Forethought and I are releasing an essay series called Better Futures, here.[1] It’s been something like eight years in the making, so I’m pretty happy it’s finally out! It asks: when looking to the future, should we focus on surviving, or on flourishing?

In practice at least, future-oriented altruists tend to focus on ensuring we survive (or are not permanently disempowered by some valueless AIs). But maybe we should focus on future flourishing, instead.

Why?

Well, even if we survive, we probably just get a future that’s a small fraction as good as it could have been. We could, instead, try to help guide society to be on track to a truly wonderful future.

That is, I think there’s more at stake when it comes to flourishing than when it comes to survival. So maybe that should be our main focus.

The whole essay series is out today. But I’ll post summaries of each essay over the course of the next couple of weeks. And the first episode of Forethought’s video podcast is on the topic, and out now, too.

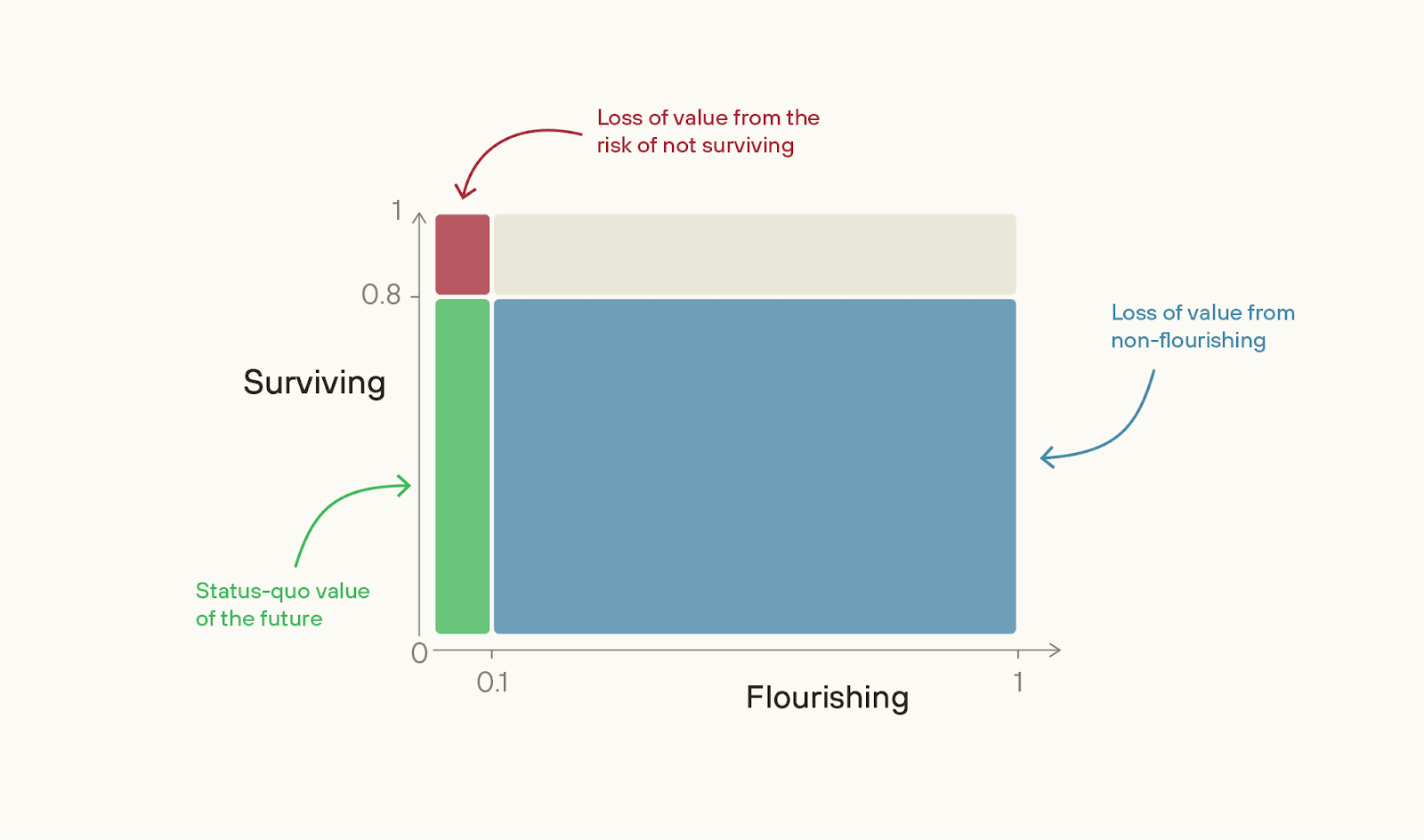

The first essay is Introducing Better Futures: along with the supplement, it gives the basic case for focusing on trying to make the future wonderful, rather than just ensuring we get any ok future at all. It’s based on a simple two-factor model: that the value of the future is the product of our chance of “Surviving” and of the value of the future, if we do Survive, i.e. our “Flourishing”.

(“not-Surviving”, here, means anything that locks us into a near-0 value future in the near-term: extinction from a bio-catastrophe counts but if valueless superintelligence disempowers us without causing human extinction, that counts, too. I think this is how “existential catastrophe” is often used in practice.)

The key thought is: maybe we’re closer to the “ceiling” on Survival than we are to the “ceiling” of Flourishing.

Most people (though not everyone) thinks we’re much more likely than not to Survive this century. Metaculus puts *extinction* risk at about 4%; a survey of superforecasters put it at 1%. Toby Ord put total existential risk this century at 16%.

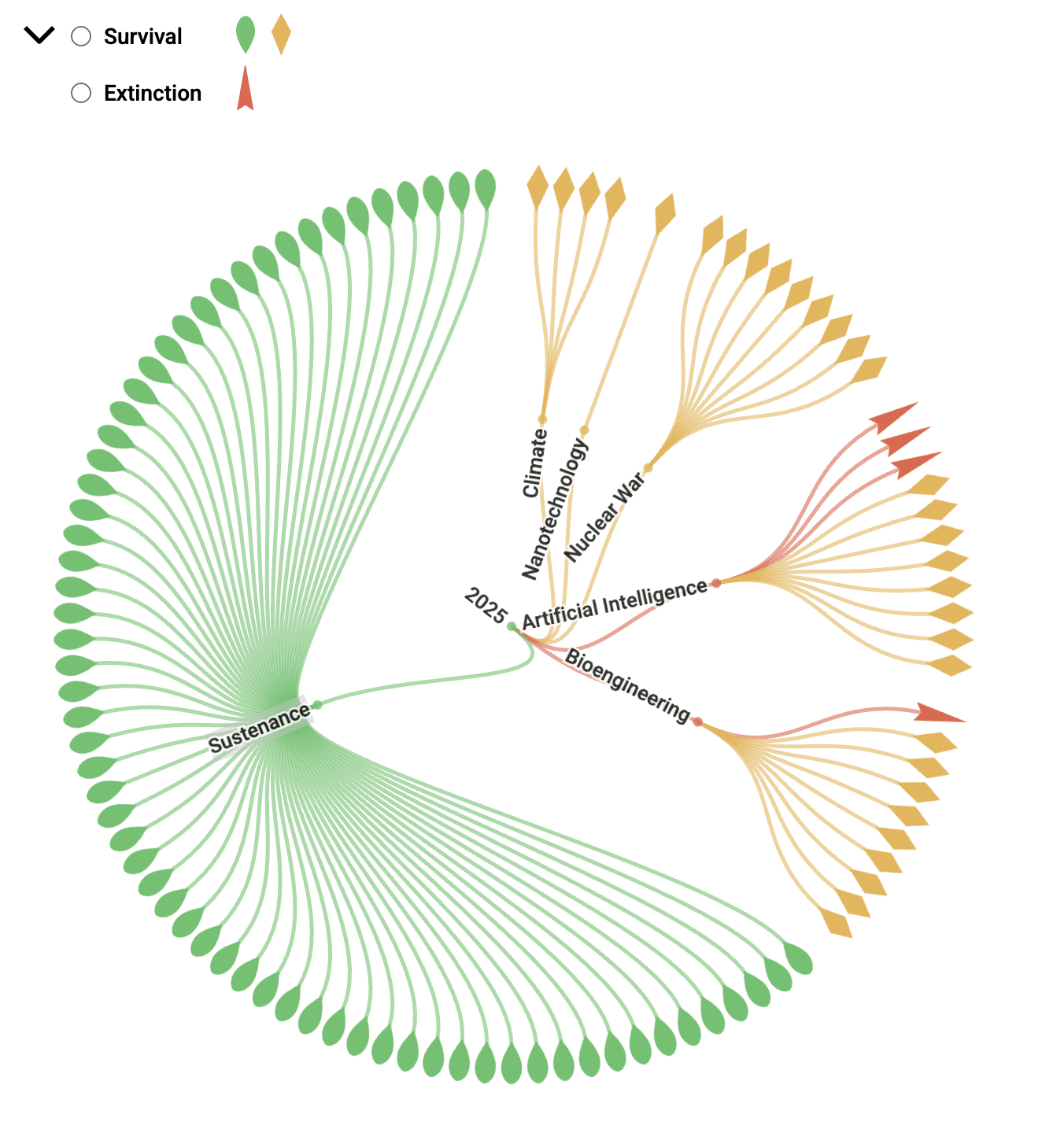

Chart from The Possible Worlds Tree.

In contrast, what’s the value of Flourishing? I.e. if near-term extinction is 0, what % of the value of a best feasible future should we expect to achieve? In the next two essays that follow, Fin Moorhouse and I argue that it’s low.

And if we are farther from the ceiling on Flourishing, then the size of the problem of non-Flourishing is much larger than the size of the problem of the risk of not-Surviving.

To illustrate: suppose our Survival chance this century is 80%, but the value of the future conditional on survival is only 10%.

If so, then the problem of non-Flourishing is 36x greater in scale than the problem of not-Surviving.

(If you have a very high “p(doom)” then this argument doesn’t go through, and the essay series will be less interesting to you.)

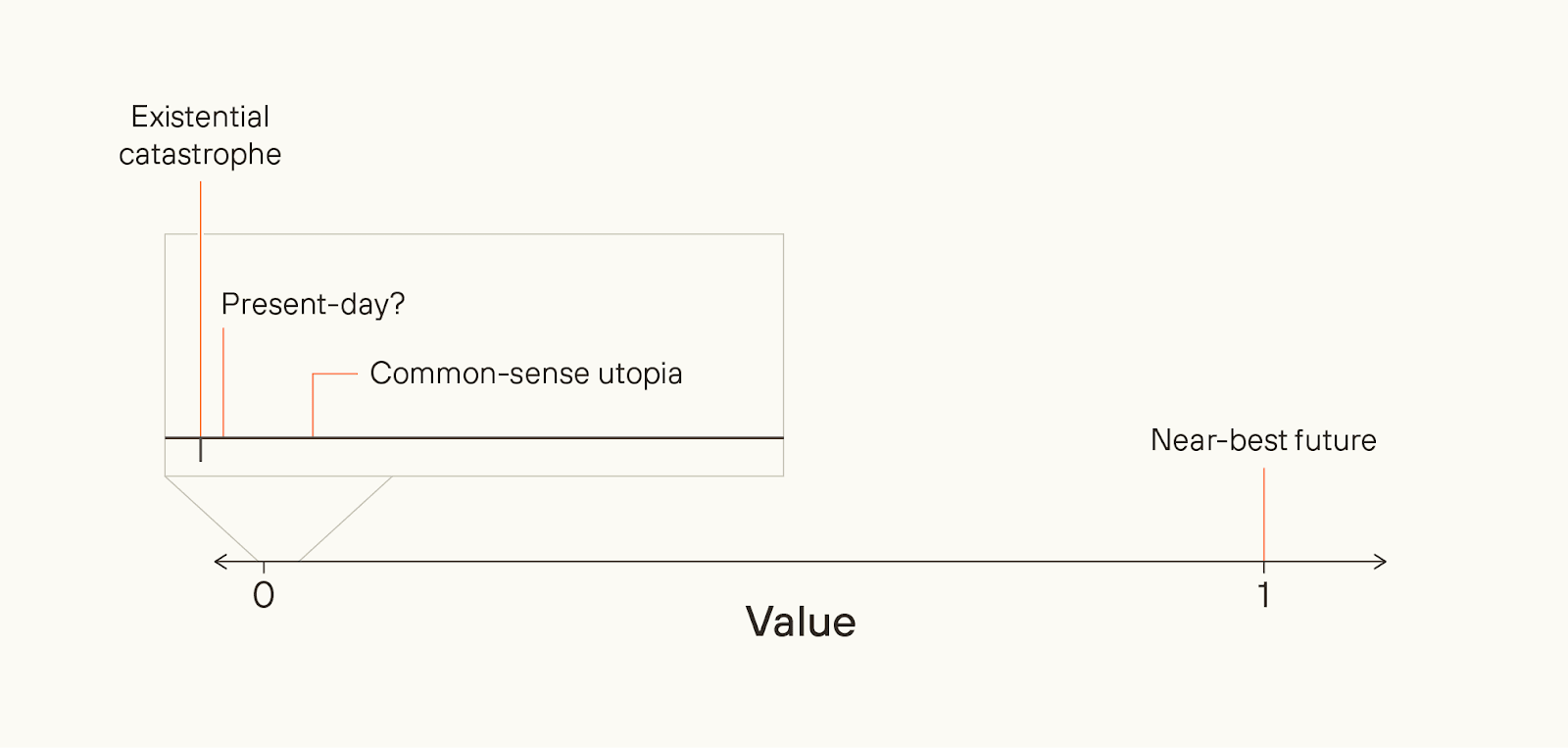

The importance of Flourishing can be hard to think clearly about, because the absolute value of the future could be so high while we achieve only a small fraction of what is possible. But it’s the fraction of value achieved that matters. Given how I define quantities of value, it’s just as important to move from a 50% to 60%-value future as it is to move from a 0% to 10%-value future.

We might even achieve a world that’s common-sensically utopian, while still missing out on almost all possible value.

In medieval myth, there’s a conception of utopia called “Cockaigne” - a land of plenty, where everyone stays young, and you could eat as much food and have as much sex as you like.

We in rich countries today live in societies that medieval peasants would probably regard as Cockaigne, now. But we’re very, very far from a perfect society. Similarly, what we might think of as utopia, today, could nonetheless barely scrape the surface of what is possible.

All things considered, I think there’s quite a lot more at stake when it comes to Flourishing than when it comes to Surviving.

I think that Flourishing is likely more neglected, too. The basic reason is that the latent desire to Survive (in this sense) is much stronger than the latent desire to Flourish. Most people really don’t want to die, or to be disempowered in their lifetimes. So, for existential risk to be high, there has to be some truly major failure of rationality going on.

For example, those in control of superintelligent AI (and their employees) would have to be deluded about the risk they are facing, or have unusual preferences such that they're willing to gamble with their lives in exchange for a bit more power. Alternatively, look at the United States’ aggregate willingness to pay to avoid a 0.1 percentage point chance of a catastrophe that killed everyone - it’s over $1 trillion. Warning shots could at least partially unleash that latent desire, unlocking enormous societal attention.

In contrast, how much latent desire is there to make sure that people in thousands of years’ time haven’t made some subtle but important moral mistake? Not much. Society could be clearly on track to make some major moral errors, and simply not care that it will do so.

Even among the effective altruist (and adjacent) community, most of the focus is on Surviving rather than Flourishing. AI safety and biorisk reduction have, thankfully, gotten a lot more attention and investment in the last few years; but as they do, their comparative neglectedness declines.

The tractability of better futures work is much less clear; if the argument falls down, it falls down here. But I think we should at least try to find out how tractable the best interventions in this area are. A decade ago, work on AI safety and biorisk mitigation looked incredibly intractable. But concerted effort *made* the areas tractable.

I think we’ll want to do the same on a host of other areas — including AI-enabled human coups; AI for better reasoning, decision-making and coordination; what character and personality we want advanced AI to have; what legal rights AIs should have; the governance of projects to build superintelligence; deep space governance, and more.

On a final note, here are a few warning labels for the series as a whole.

First, the essays tend to use moral realist language - e.g. talking about a “correct” ethics. But most of the arguments port over - you can just translate into whatever language you prefer, e.g. “what I would think about ethics given ideal reflection”.

Second, I’m only talking about one part of ethics - namely, what’s best for the long-term future, or what I sometimes call “cosmic ethics”. So, I don’t talk about some obvious reasons for wanting to prevent near-term catastrophes - like, not wanting yourself and all your loved ones to die. But I’m not saying that those aren’t important moral reasons.

Third, thinking about making the future better can sometimes seem creepily Utopian. I think that’s a real worry - some of the Utopian movements of the 20th century were extraordinarily harmful. And I think it should make us particularly wary of proposals for better futures that are based on some narrow conception of an ideal future. Given how much moral progress we should hope to make, we should assume we have almost no idea what the best feasible futures would look like.

I’m instead in favour of what I’ve been calling viatopia, which is a state of the world where society can guide itself towards near-best outcomes, whatever they may be. Plausibly, viatopia is a state of society where existential risk is very low, where many different moral points of view can flourish, where many possible futures are still open to us, and where major decisions are made via thoughtful, reflective processes.

From my point of view, the key priority in the world today is to get us closer to viatopia, not to some particular narrow end-state. I don’t discuss the concept of viatopia further in this series, but I hope to write more about it in the future.

- ^

This series was far from a solo effort. Fin Moorhouse is a co-author on two of the essays, and Phil Trammell is a co-author on the Basic Case for Better Futures supplement.

And there was a lot of help from the wider Forethought team (Max Dalton, Rose Hadshar, Lizka Vaintrob, Tom Davidson, Amrit Sidhu-Brar), as well as a huge number of commentators.

It's worth noting that it's realistically possible for surviving to be bad, whereas promoting flourishing is much more robustly good.

Survival is only good if the future it enables is good. This may not be the case. Two plausible examples:

Survival could still be great of course. Maybe we'll solve wild animal suffering, or we'll have so many humans with good lives that this will outweigh it. Maybe we'll make flourishing digital minds. But I wanted to flag this asymmetry between promoting survival and promoting flourishing, as the latter is considerably more robust.

I think this is an important point, but my experience is that when you try to put it into practice things become substantially more complex. E.g. in the podcast Will talks about how it might be important to give digital beings rights to protect them from being harmed, but the downside of doing so is that humans would effectively become immediately disempowered because we would be so dramatically outnumbered by digital beings.

It generally seems hard to find interventions which are robustly likely to create flourishing (indeed, "cause humanity to not go extinct" often seems like one of the most robust interventions!).

A lot of people would argue a world full of happy digital beings is a flourishing future, even if they outnumber and disempower humans. This falls out of an anti-speciesist viewpoint.

Here is Peter Singer commenting on a similar scenario in a conversation with Tyler Cowen:

COWEN: Well, take the Bernard Williams question, which I think you’ve written about. Let’s say that aliens are coming to Earth, and they may do away with us, and we may have reason to believe they could be happier here on Earth than what we can do with Earth. I don’t think I know any utilitarians who would sign up to fight with the aliens, no matter what their moral theory would be.

SINGER: Okay, you’ve just met one.

I apologize because I'm a bit late to the party, haven't read all the essays in the series yet, and haven't read all the comments here. But with those caveats, I have a basic question about the project:

Why does better futures work look so different from traditional, short-termist EA work (i.e., GHW work)?

I take it that one of the things we've been trying to do by investing in egg-sexing technology, strep A vaccines, and so on is make the future as good as possible; plenty of these projects have long time horizons, and presumably the goal of investing in them today is to ensure that—contingent on making it to 2050—chickens live better lives and people no longer die of rheumatic heart disease. But the interventions recommended in the essay on how to make the future better look quite different from the ongoing GHW work.

Is there some premise baked into better futures work that explains this discrepancy, or is this project in some way a disavowal of current GHW priorities as a mechanism for creating a better future? Thanks, and I look forward to reading the rest of the essays in the series.

Copied from my comment on LW, because it may actually be more relevant over here where not everyone is convinced about alignment being hard. It's a really sketchy presentation of what I think are strong arguments for why the consensus on this is wrong on this.

I really wish I could agree. I think we should definitely think about flourishing when it's a win/win with survival efforts. But saying we're near the ceiling on survival looks wildly too optimistic to me. This is after very deeply considering our position and the best estimate of our odds, primarily surrounding the challenge of aligning superhuman AGI (including surrounding societal complications).

There are very reasonable arguments to be made about the best estimate of alignment/AGI risk. But disaster likelihoods below 10% really just aren't viable when you look in detail. And it seems like that's what you need to argue that we're near ceiling on survival.

The core claim here is "we're going to make a new species which is far smarter than we are, and that will definitely be fine because we'll be really careful how we make it" in some combination with "oh we're definitely not making a new species any time soon, just more helpf... (read more)

Citation needed on this point. I you're underrepresenting the selection bias for a start - it's extremely hard to know how many people have engaged with and rejected the doomer ideas since they have far less incentive to promote their views. And those who do often find sloppy argument and gross misuses of the data in some of the prominent doomer arguments. (I didn't have to look too deeply to realise the orthogonality thesis was a substantial source of groupthink)

Even within AI safety workers, it's far from clear to me that the relationship you assert exists. My impression of the AI safety space is that there are many orgs working on practical problems that they take very seriously without putting much credence in the human-extinction scenarios (FAR.AI, Epoch, UK AISI off the top of my head).

One guy also looked at the explicit views of AI experts and found if anything an anticorrelation between their academic success and their extinction-related concern. That was looking back over a few years and obviously a lot can change in that time, but the arguments for AI extinction ha... (read more)

... What is surprising about the world having a major failure of rationality? That's the default state of affairs for anything requiring a modicum of foresight. A fairly core premise of early EA was that there is a truly major failure of rationality going on in the project of trying to improve the world.

Are you surprised that ordinary people spend more money and time on, say, their local sports team, than on anti-aging research? For most of human history, aging had a ~100% chance of killing someone (unless something else killed them first).

I think that most of classic EA vs the rest of the world is a difference in preferences / values, rather than a difference in beliefs. Ditto for someone funding their local sports teams rather than anti-aging research. We're saying that people are failing in the project of rationally trying to improve the world by as much as possible - but few people really care much or at all about succeeding at that project. (If they cared more, GiveWell would be moving a lot more money than it is.)

In contrast, most people really really don't want to die in the next ten years, are willing to spend huge amounts of money not to do so, will almost never take actions that they know have a 5% or more chance of killing them, and so on. So, for x-risk to be high, many people (e.g. lab employees, politicians, advisors) have to catastrophically fail at pursuing their own self-interest.

Thanks for sharing!

I'm not sure if you intend to do a separate post on it, so I'll include this feedback here. You argue that:

This seems quite unclear to me. In the supplement you describe one reason it might be false (uncertainty about future algorithmic efficiency). But it seems to me there is a mu... (read more)

One thing I think the piece glosses over is that “surviving” is framed as surviving this century—but in longtermist terms, that’s not enough. What we really care about is existential security: a persistent, long-term reduction in existential risk. If we don’t achieve that, then we’re still on track to eventually go extinct and miss out on a huge amount of future value.

Existential security is a much harder target than just getting through the 21st century. Reframing survival in this way likely changes the calculus—we may not be at all near the "ceiling for survival" if survival means existential security.

I'm not sure how this factors into the math but I also just feel like there's an argument to be made that a vision of flourishing is more inspiring and feels more worth fighting for, which would in turn become a big factor in how hard we actually fight for it (and in the process, how hard we fight for survival), which would in term increase the probability of both flourishing and survival happening. I.e. focusing on flourishing would actually make survival more likely. Like the old saying goes, "without a vision, people perish".

relevant semi- related readings

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/s/wmqLbtMMraAv5Gyqn

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/W4vuHbj7Enzdg5g8y/two-tools-for-rethinking-existential-risk-2

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zuQeTaqrjveSiSMYo/a-proposed-hierarchy-of-longtermist-concepts

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/fi3Abht55xHGQ4Pha/longtermist-especially-x-risk-terminology-has-biasing

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/wqmY98m3yNs6TiKeL/parfit-singer-aliens

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zLi3MbMCTtCv9ttyz/formalizing-exti... (read more)

It isn't enough to prevent a catastrophe to ensure survival. You need to permanently reduce x-risk to very low levels aka "existential security". So the question isn't how likely flourishing is after preventing a catastrophe, it's how likely flourishing is after achieving existential security.

It seem... (read more)

- You might be interested in the term "thrutopia", which tries to achieve a similar thing and is gaining traction in semi-adjacent circles

... (read more)On flourishing v. surviving:

I heard this story from Joe Hudson about a tennis player doing practice. She could hit the basket smth like 6/10 times. One day her coach put a coin instead and told her to hit the coin. She never hit the coin, but she would have hit the basket 9/10 times.

Where we aim can matter a lot for the outcomes we get, even without reaching "the goal" (same as it matters what questions you ask

I agree that flourishing is very important. I have thought since around 2018 that the largest advantage for the long-term future of resilience to global catastrophes is not preventing extinction, but instead increasing flourishing, such as reducing the chance of other existential catastrophes like global totalitarianism, or making it more likely that better values end up in AI.

Executive summary: In this introductory post for the Better Futures essay series, William MacAskill argues that future-oriented altruists should prioritize humanity’s potential to flourish—not just survive—since we are likely closer to securing survival than to achieving a truly valuable future, and the moral stakes of flourishing may be significantly greater.

Key points:

- Two-factor model: The expected value of the future is the product of our probability of Surviving and the value of the future conditional on survival.

- We’re closer to securing survival than

... (read more)I agree that we should shift our focus from pure survival to prosperity. But I disagree with the dichotomy that the author seems to be proposing. Survival and prosperity are not mutually exclusive, because long-term prosperity is impossible with a high risk of extinction.

Perhaps a more productive formulation would be the following: “When choosing between two strategies, both of which increase the chances of survival, we should give priority to the one that may increase them slightly less, but at the same time provides a huge leap in the potential for prosp... (read more)

It is stated that, conditional on extinction, we create around zero value. Conditional on using CDT to compute our marginal impact, this is true. But conditional on EDT, this is incorrect.

Conditional on EDT:

- 84+% of the resources we would not grab, in case Earth does not create a space-faring civilization (i.e., "extinction"), would still be recovered by other space-faring civilizations. Such that working on reducing extinction has a scale 84+% lower than when assuming CDT. (ref)

- Even if we go extinct, working on flourishing or extinction still cre... (read more)

Really enjoyed this post! It made me realize something important: if we’re serious about creating good long-term futures, maybe we should actively search for scenarios that do more than just help humanity survive. Scenarios that actually make life deeply meaningful.

Recently, an idea popped into my head that I keep coming back to. At first, I dismissed it as a bit naive or unrealistic, but the more I think about it, the more I feel it genuinely might work. It seems to solve several serious problems at once. For example destructive competition, the los... (read more)

The question in the title is good food for thought, and I'm not sure if one should aim for survival or flourishing from a reasoned point of view. If making the decision based on intuition, I'd choose flourishing, just because it's what excites me about the future.

Currently I'm not convinced that a near-best future is hard to achieve, after reading (some of) part 2 of 6 from the Forethought website. One view is that the value of the future should be judged by those in the future, and that as long as the world is changing we don't know the value of it yet&nb... (read more)

I agree with the general thrust of this post - at least the weak version that we should consider this to be an unexplored field, worth putting some effort into. But I strong disagree with the sentiment here:

Not ... (read more)

wow this really mind blowing for me as i think what you’re calling “flourishing” and what I’ve been calling “living risk” are pointing at the same neglected frontier. We’ve rightly invested enormous effort into ensuring survival into not dying, not being permanently disempowered. But survival is not the same as life, and we risk mistaking the floor for the ceiling.

If humanity makes it through this century but ends up culturally hollow, emotionally arid, or morally locked into a narrow vision, then we’ve technically survived but failed to flourish. That’s t... (read more)

Just a suggestion about "flourishing": upon abandoning the "state of nature" in prehistory, human beings entered a process of cultural evolution that can also be called the "civilizing process."

This process basically consists of controlling, through cultural means, the aggressiveness characteristic of all higher mammals: a necessary instinct in the struggle for scarce resources and one that is part of the evolutionary factors. Human beings don't need aggression because, thanks to cooperation and intelligence, they can achieve abundance. In an economy of sc... (read more)