Negotiations and pressure campaigns have proven effective at driving corporate change across industries and movements. I expect that AI safety/governance can learn from this!

The basic idea:

- The runaway success of effective animal advocacy has been sweeping corporate reform

- Similar tactics have been successful across social movements

- GovAI to ??? to PauseAI: Corporate campaigns need an ecosystem of roles and tactics

Possible next steps

- Pragmatic research: ask prioritisation, user interviews, and message testing

- Start learning by doing

- Work extensively with volunteers (and treat them like staff members)

- Moral trade: longtermist money for experienced campaigner secondments

The runaway success of effective animal advocacy has been sweeping corporate reform

Animal advocates, funded especially by Open Philanthropy and other EA sources, have achieved startling success in driving corporate change over the past ~decade. As Lewis Bollard, Senior Program Officer at Open Philanthropy, writes:

A decade ago, most of the world’s largest food corporations lacked even a basic farm animal welfare policy. Today, they almost all have one. That’s thanks to advocates, who won about 3,000 new corporate policies in the last ten years…

In 2015-18, as advocates secured cage-free pledges from almost all of the largest American and European retailers, fast food chains, and foodservice companies. Advocates then extended this work globally, securing major pledges from Brazil to Thailand. Most recently, advocates won the first global cage-free pledges from 150 multinationals, including the world’s largest hotel chains and food manufacturers.

A major question was whether these companies would follow through on their pledges. So far, almost 1,000 companies have — that’s 88% of the companies that promised to go cage-free by the end of last year. Another 75% of the world’s largest food companies are now publicly reporting on their progress in going cage-free.

Some advocates establish professional relationships with companies and encourage them to introduce improvements. Others use petitions, protests, and PR pressure to push companies over the line.

Almost everyone who investigates these campaigns thoroughly seems to conclude that they’re exceptionally cost-effective at making real improvements for animals, at least in the short term. There are both ethical and strategic reasons why some animal advocates doubt that these kinds of incremental welfare tactics are a good idea, but I lean towards thinking that the indirect effects are neutral to positive, while the direct effects are robustly good. There are other promising tactics that animal advocates can use, but the track record and evidence base for corporate welfare campaigns is unusually strong.

Of course, animal advocacy is different to AI Safety. But something that has been so successful in one context seems worth exploring seriously in others. And oh wait, it has worked in more than one context already…

Similar tactics have been successful across social movements

In my research into other social movements’ histories, I found strong evidence that pressure tactics can be effective at changing companies’ behaviour or disrupting their processes[1]:

- US anti-abortion activists seem to have successfully disrupted the supply of abortion services and may have reduced abortion rates.

- Anti-death penalty activists successfully disrupted the supply of lethal injection drugs.

- Pressure campaigns likely accelerated Starbucks and other chains’ participation in Fair Trade certification schemes.

- Prison riots and strikes seem to have encouraged the creation of new procedures and rules for prisoners.

There are lots of caveats, concerns, and intuition-building anecdotes in each of the case studies. But I wanted to highlight the general pattern.

GovAI to ??? to PauseAI: Corporate campaigns need an ecosystem of roles and tactics

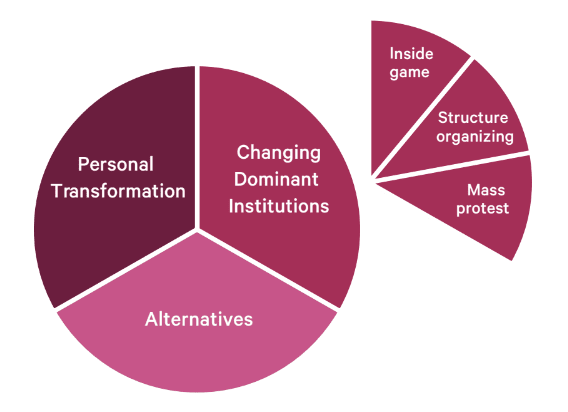

Successful corporate reform campaigns in animal welfare and other movements suggest an important principle — the need for an “ecology” of different organisations, roles, and tactics.

In animal welfare campaigns, ‘good cop’ orgs who work closely with industry (e.g. Compassion in World Farming) are complemented by ‘bad cop’ orgs willing to use pressure tactics (e.g. The Humane League).

There’s scope for a broader spectrum still, from professional, expert groups for credibility (e.g. animal welfare scientists, vets, nutritionists) through to grassroots activist and mass mobilisation groups (e.g. Direct Action Everywhere, Animal Rising). It seems like AI governance is doing better at these extremes. Most of its weight is behind the ‘credible experts’ with groups like GovAI, CSER, and CSET — which I do think is the best place to start.

Some orgs have started to spring up at the other end of the spectrum too, like the Campaign for AI Safety and PauseAI[2]. This seems good to me! Having organisations that use radical tactics seems to increase identification with and support for the more moderate groups. Many academics with expertise relevant to social movements seem to think that “having both radical and moderate flanks” and “the strategic use of nonviolent disruptive tactics” are quite important for social movement success.

But we’re missing the space in between these extremes that focuses on consistent pressure on companies, roughly what the Anyi Institute calls “structure organizing”; working “to build an organized base of people to pressure decision makers around certain demands.”[3]

The model that seems to be missing is at the overlap of three things[4]:

- Structure: a nonprofit with permanent, full-time staff applying consistent pressure on particular companies (not flash-in-the-pan or solely volunteer-led)

- Audience: targeting companies (not consumers, or governments). You might do some public outreach to recruit more activists or raise the stakes for the companies you target, but the goal is to feed the specific campaign.

- Some confrontation: you can start with the carrot (good for the world, good PR), but you might need to resort to the stick (bad PR, wasted company time, some missed profit) if they resist. Similarly, you can start with friendly meetings; you might need to get public.

There are lots of groups in effective animal advocacy that sit in this space. To name a few[5]…

- The Humane League

- Mercy For Animals

- Sinergia Animal

- Anima International

- Animal Equality

- Essere Animali

- Vegetarianos Hoy

- Equalia

- Humánny pokrok

Caveats and concerns

There are many valid caveats and concerns to the general argument above, but I don’t think any of these are sufficient to overturn the conclusion.

Here are some brief ideas:

- We have uncertainties about proposed governance asks… but some seem promising

- This seems confrontational… but nonviolent confrontation has its place (also), and you don’t always even need to resort to confrontation[6]

- This is more technical than most pressure campaigns… but safety (plus equity and employment) concerns have underpinned past successful campaigns on tech issues[7]

Let me know in the comments if you have other concerns or would find it helpful if I fleshed out my counterarguments to any of the above!

Possible next steps

This isn’t meant to be anything like a full “roadmap”, but I wanted to provide at least a smattering of suggestions for next steps.

Pragmatic research: ask prioritisation and message testing

Research from groups like GovAI is mostly academic or advisory in style. Of course there’s an important role for that. But to prioritise actions, you need something more pragmatic.

I’m a big fan of Charity Entrepreneurship’s process for generating lots of possible intervention ideas, then narrowing the scope down to identify those that seem most promising. Rethink Priorities’ Existential Security Team does something similar.

An alternative way to contribute to pragmatic research is through message testing. There’s been some work on this already, like by Vael Gates and Campaign for AI Safety, but there’s room to get more systematic (compare Pax Fauna on animal advocacy messaging) and rigorous (compare Schubert, Caviola, and Faber on the psychology of x-risk).

Start learning by doing

Desk-based research isn’t enough. You need to get out there; start meeting your stakeholders and encountering real conditions, needs, bottlenecks.

Fish Welfare Initiative’s top “lesson learned” from their first 2.5 years was that “It’s often better to explore by exploiting (as opposed to theoretical desk research)”:

Initially we had a fairly discrete research process, where we aimed to answer the following 4 big prioritization questions separately via desk research: (1) Which (fish) species should we work to help? (2) Which country should we work in? (3) Which welfare improvement(s) should we make? (4) Which approach(es) should we take?... However, the reality is that, however hard we tried to answer these questions separately… these questions are all interlinked—you can’t, for instance, work on Atlantic salmon welfare in India because there are no Atlantic salmon farmed here. This is something we would have better internalized had we gone out into the field earlier (for instance to actually visit farms and talk with companies in the countries like India where we were interested in working)... we spent about a year trying to answer our prioritization questions separately, and largely doing it through desk research… we believe we could have cut that down to roughly half the time. Now, one of our organizational mottos is “explore by exploiting”: We often think the best way to learn how to do something is just to try to do it. The true bottlenecks usually become clear in the attempt.

This maps on pretty well to the absurdly consistent startup advice to do regular user interviews. Although the style of conversation looks different, you can use these to understand:

- Value (needs and demand)

- Usability (e.g. whether a certain format or message makes sense)

- Feasibility (e.g. whether you can actually offer what’s needed)

But even this can only take you so far; you also need to actually prototype or pilot “minimum viable products”. This is probably easier with tech products than with complex social issues, but the underlying sentiment has merit.

Work extensively with volunteers (and treat them like staff members?)

I have the sense that a bunch of longtermists have internalised the opening message of this old 80k post a bit too hard and think that volunteering is ~useless.

But try telling that to effective animal advocacy groups; I suspect many of them would collapse without this kind of unpaid support. Corporate campaigns benefit from both professionals and volunteers.

The more obvious form of volunteering is the quick or low-effort kind, like online activism or joining ad hoc protests. But consider also treating some volunteers like staff members, with defined responsibilities, benefits, and managers.

Moral trade: longtermist money for experienced campaigner secondments

Crudely, AI safety seems bottlenecked more by expertise than by money, while animal advocacy has expertise but lacks money. Some sort of swap (moral trade) seems possible.

Of course, this is a simplification. But AI Safety has tended to be bottlenecked more by various types of talent (plus management capacity, limits on the speed of growth, etc) than by funding.[8] It’s a mixed picture in animal advocacy; talent is still needed, but funding seems a comparably big constraint.

I can imagine AI safety orgs doing something like paying for experienced animal advocacy campaigners to go on secondments or provide advice. Salaries are usually constrained by a bunch of organisational considerations that perhaps grants to other orgs are not — so maybe the orgs could pay what they value the support at (which could be very high figures, by animal advocacy’s standards)?

Of course, I can imagine a whole bunch of reasons why this might not work out in practice. Maybe I’m overcomplicating it and there are simpler answers:

- Put out a job ad with a decent salary. After all, corporate campaigns exist outside of animal advocacy, so you might get applications from experienced activists.

- Use existing resources and public advice by advocates or research orgs.

- Find informal advisors with experience from other movements, perhaps including effective animal advocacy.

Thanks to Patrick Levermore and Holly Morgan for feedback on drafts of this post.

- ^

For sources and detailed evidence, see row 7 of this spreadsheet, which describes the relevant sections of each report.

- ^

These orgs are new and still pretty tiny though. E.g. a recent CAS update notes that a UK petition only has 38 signatures. 38!? For reference, the two petitions I found via The Humane League UK’s site had 374,791 and 19,826 signatures, and it needs 10,000 signatures to get a government response.

- ^

We could think about (partly overlapping) spectrums or portfolios of asks/demands, tactics, target audiences, and structures. I suspect a healthy social movement needs at least some groups at different positions on all of these.

- ^

I think I conflated these three somewhat in this post; if I’d spent longer, ideally I would have argued for each of them separately. Let me know if you’d be keen for me to write a follow-up that does so.

- ^

I made this list from memory, so apologies to any orgs I mischaracterised. Feel free to contact me if you disagree. Also, there are others that share the structure and audience but eschew the confrontational side, most notably Compassion In World Farming. And others that focus on replacing animal products with alternatives rather than animal welfare.

- ^

If I recall correctly, when The Humane League UK first got set up, they won something like ~50 corporate commitments in their first year with only one staff member, mostly just by asking what no one had asked before. But their annual reports don’t start until their third year of existence, so I can’t quickly verify this.

- ^

- ^

This is great — thanks for writing it up! I think you're spot-on that this is a big gap in the AI Safety ecosystem right now.

In fact, I recently stepped away from working on corporate campaigns at The Humane League to explore this very thing, so it feels very topical and is something I've been thinking about quite a bit. (As a side note, if anyone is thinking about or interested in working on this, I'd love to connect).

Anyway, just a couple of thoughts I want to add:

One persistent concern I have is that this may only be true of industries and movements where the cost of a campaign can plausibly outweigh the costs of giving in to campaigners' asks.

For context, during my time working on animal welfare campaigns, I became increasingly convinced that the decision of whether or not to give in to a campaign was a pretty simple financial equation for a corporate target. Something like the following:

Give in to (campaigner's demands) if (estimated financial cost incurred from withstanding campaign) >= (estimated cost of giving into campaigners' demands)

This is an oversimplification, of course. Corporations are full of humans who act for many reasons beyond profit maximization, including just doing the right thing. Also, the cost incurred from a campaign is almost surely a very uncertain and complex estimation. [1]

But still, I think some simple equation like the one above explains the vast majority of variation in whether or not a target gives in.[2] Put simply, a campaign has to have enough firepower to incur costs sufficiently high that giving in becomes cheaper for the corporate target than withstanding the campaign.

So, here's where I get concerned: The costs for a large food company switching to use cage-free eggs, for example, are not only relatively low, but more importantly, they are bounded. You can start sourcing cage-free eggs in a few weeks or months and pay a certain low-double-digit % more for a single ingredient in your supply chain. For a lot of food companies, it's easy to see how a moderately-sized campaign can become more expensive than just sourcing cage-free eggs.[3]

But what about AI? When it comes to falling behind even slightly in a corporate arms race for a technology as transformative as this, it's not clear to me that the costs are that low — in fact, it's not clear to me that the costs are bounded at all. For example, Google was the classic example of an entrenched leader when it came to web search (>90% market share), and Bing rolling out Sydney was enough to put Google in full "code-red" mode.

So, if the potential financial benefits of leading on AI are as massive as these companies (and me, and most folks in AI safety) seem to believe they are, it implies that a campaign would need to cause a ridiculous amount of financial risk to move a company to actually implement meaningful safeguards. [4]

One interesting thing I'm noticing — perhaps owing to the general disposition of people interested in AI safety — is that these groups are definitely radical in their asks (total training run moratoriums) but not so radical in tactics (their protests, as far as I can tell, have been less confrontational than many THL campaigns).

So I just think there is still a lot of implied space, further down the spectrum, for the sort of tactics that Just Stop Oil or Direct Action Everywhere are using. [5]

Another problem I've been running into is that, even where general categories of asks seem promising, there are very few specifics in place. For a company to commit to external auditing, for example, we have to know what the audits are and who conducts them and what models they apply to. From the conversations I've had with folks in policy so far, it appears this is all still in the works. Or, as Scott Alexander says, "The Plan Is To Come Up With A Plan"

Of course, you need specific language to make asks of a corporate campaign target. And, troublingly, vague language is just the kind of thing that I think companies love. Food businesses are happy to voluntarily make vague commitments (like "We are committed to animal welfare and will strive to make sure our animals can lead happy and healthy lives") and much more reluctant to make concrete commitments that open them up to liability (like "We will meet the UEP certified cage-free guidelines".) I'm worried a lot of the commitments you could get from tech companies and AI labs right now look more like the former, including the recent one made in collaboration with the White House.

One gap in the AI Safety space that I think could mitigate this problem would be having a highly trusted third-party entity that serves as a meta-certifier that can certify different standards or auditing orgs or evals. For example, when animal groups were asking for slower-growing breeds to be used, they didn't actually know what breeds were best, so they secured a bunch of commitments that said something like "We commit to, by 2024, using breeds approved by the certifier G.A.P. pending their forthcoming research with the University of Guelph".

I wish the AI Safety space had some certifier such that tech companies could commit to testing all new frontier models on, and publicly reporting the results of, benchmarks approved by that certifier in the future. I think government bodies can often serve this role, but it seems like we don't have that yet either, so we can't ask for these sorts of specific-but-TBD commitments.

By this I mean it relies on questions like how bad PR, employee satisfaction, relationships with corporate partners, future government regulation, etc. all impact future revenue. Also, on the other side of the equation, the costs of giving in might be simple in some industries (it's easy to forecast how much it costs to transition to sourcing cage-free eggs), but there are also hard-to-measure benefits (using cage-free eggs is good for PR and marketing in its own right) and ambiguous lingering questions (will activists now think we are an easy target?) that probably complicate that side of the equation, too. ↩︎

This is the product of speculation from my experiences, rather than any actual statistical analysis or rigorous thought, so take it with a big grain of salt. ↩︎

I haven't read much about the historical examples you've cited from the private sector (abortion services and fair-trade coffee). I'd be curious to see if the financial incentives seem to be driving these too. But I think part of why loads of bad PR has failed to significantly slow the fossil fuel industry, for example, is that the benefits of selling more oil often just vastly exceeds the costs of bad PR from activists. ↩︎

This assumes, of course, that meaningful safeguards are costly. If they weren't, hopefully the inside-game collaborative stuff would be enough. ↩︎

By this I only mean that, descriptively, I don't see anyone currently using radical tactics in AI Safety — at least compared with other major social movements. I'm not making any normative claims about whether such tactics are, or ever will be, useful or justified. Also, I hope it goes without saying, but I'm not talking about violence against people, which I take to never be justified. ↩︎

Cool! Exciting that you're working on this, and thanks for your thoughts.

I think the bar for "disrupting supply / business as usual" is lower. A couple of the other social movement examples I cited were just this. I haven't thought much about what that might look like in the context of AI safety, but it might be comparable to forcing a localised 'pause' on (some aspects of) frontier AGI development, which might be good.

If you're going beyond that though, and trying to encourage meaningful corporate change, then I think maybe you just want to do some brainstorming about what sorts orgs or asks might be more promising.

For example, I found evidence that “boycotts of specific companies across their entire product range may be a more promising tactic for disrupting the supply of a product than boycotts of a specific product type across all companies.” (anti-abortion). So maybe e.g. Microsoft might be more vulnerable to pressure campaigns (across their entire product range or company) for failures relating to BingChat than more specialised companies like OpenAI would be for failures relating to ChatGPT.

There are different kinds of costs you could try to impose on non-complying companies. Immediate revenue costs, PR costs, risks of harsh regulation, wasted company time, etc. It might just be about matching the cost to the company and the campaign.

So something you highlight as a downside for this kind of campaign in AI safety could be used as an asset in your arsenal:

You could use these as pressure points, as opposed to being things that the company needs to shoulder in order to cave to the campaign. E.g. going back to the 'disruption' idea, maybe this perspective means that something that risks slowing the company down by just a few months is a surprisingly powerful tool/threat against them.

Are you highlighting this as just something like 'here's a risk corporate campaigns against AI labs/companies would need to look out for', or 'here's something that makes these kinds of campaigns much less promising'? I agree with the former but not the latter.

Alignment Research Center evals? Apollo Research evals? Maybe you mean something more specific and I'm just not following the distinction you're making.

(I intuitively agree these things would ideally be done by governments, or government-funded bodies. But I don't know much about the precedent from regulation of other industries.)

Thank you for responding and sorry for the delayed reply.

I'm not totally sure what the distinction is between disrupting business as usual and encouraging meaningful corporate change — in my mind, corporate campaigns do both, the former in service of the latter. Maybe I'm misunderstanding the distinction there.

That being said, I am much less certain than I was a few weeks ago about the "no costs from disrupted business can be sufficiently high to trigger action on AI safety" take, primarily because of what you pointed out: the corporate race dynamics here might make small disruptions much more costly, rather than less. In fact, the higher the financial upside is, the more costly it could be to lose even a tiny edge on the competition. So even if the costs of meaningful safeguards go up in competitive markets, so too do the costs of PR damage or the other setbacks you mention. I hadn't thought of this when I wrote my comment but it seems pretty obvious to me now, so thanks for pointing it out.

I'm hoping to think more rigorously about why corporate campaigns work in the upcoming weeks, and might follow up here with additional thoughts.

Both, I think. I'm still working on this because I'm optimistic that meaningful + robust policies with really granular detail will be developed, but if they aren't, it would make campaigns less promising in my mind. Maybe what's going on is something like the Collingridge dilemma, where it takes time for meaningful safeguards to be identified, but time also makes it harder to implement those safeguards.

Curious to hear why you think campaigns are just as promising even if there aren't detailed asks to make of labs, if I'm understanding you correctly.

Yeah, in my mind, the animal welfare to AI safety analogy is something like this, where (???) is the missing entity that I wish existed:

G.A.P : Cooks Venture :: (???) : ARC/Apollo

This is to say that ARC and Apollo are developing eval regimes in the same way Cooks Venture develops slower-growing breeds, but a lab would probably be very reluctant to commit to auditing with a single partner into perpetuity regardless of how demanding the audits are in the same way a food company wouldn't want to commit to exclusively sourcing breeds developed by Cooks Venture. And activists, too, would have reason to be concerned about an arrangement like this since the chicken breed (or model eval) developer's standards could drop in the future.

So I wish there was some nonprofit or govt committee with a high degree of trust and few COIs who was tasked with certifying the eval regimes developed by ARC and Apollo (or those developed by academics, or even by labs themselves) — hence why I refer to them as a sort of meta-certifier. Then a lab could commit to something like "all future models will undergo evaluation approved by (meta-certifying body) and the results will be publicly shared," even if many of the specifics this would entail don't exist today.

On reflection, though, I really don't know enough about the AI safety landscape to say with confidence how useful this would be. So take it with a big grain of salt.

Hello!

Did you ever do this research on why corporate campaigns work? And if so, would you share it? Thanks!

I'm in the early stages of corporate campaign work similar to what's discussed in this post. I'm trying to mobilise investor pressure to advocate for safety practices at AI labs and chipmakers. I'd love to meet with others working on similar projects (or anyone interested in funding this work!). I'd be eager for feedback.

You can see a write-up of the project here.

Hi Jamie. Extremely interesting post! I'm giving my initial thoughts as an animal welfare researcher who has also participated in animal activism and AI protest.

I think I agree with all of these points, with the tentative exception of the 2nd.

I think adding more 'bad cop' advocacy groups into the mix could help motivate (or enforce?) companies to actually act on their intentions. After all, the behaviour-intention gap is real... and it's hard to know their true intentions.

Besides, it could also be that the advocacy groups start by targeting companies that are maybe less frontier but lagging behind on safety commitments or actions. This could help diffuse safety norms faster, and reduce race dynamics where leading labs feel the push to stay ahead of less safety-conscious orgs.

I believe the financial system is well-positioned for "consistent pressure on companies". I have more to say on this based on my own work experience, so if anyone is interested feel free to reach out.

Great post. I think there is a key difference between animal advocacy (and the other social movements mentioned) and AI x-safety though, that isn't being appreciated enough. Namely, that AI extinction risk is not about advocating for marginalised/oppressed groups, or those with no voice, or even anything related to "do gooding" at all. It's no longer even about about saving future generations. It's about personal survival for each and every one of us and our families and friends, in the near term future. Personal survival for the people that make up the corporations that are pushing AGI development. It's not about ethics, or trade-offs between profit and CSR or ESG, or competition between companies and nations. It's not even about MAD. It's unilaterally assured destruction. No one can safely wield the technology. It needs to be curtailed globally.

With all this in mind, it should really be an easier sell to get corporations to stop. I'm not hopeful that this will happen without government regulation and international treaties though (because of attitudes like this). Hopefully that will happen in time, but we need to be doing all we can to push for it (including corporate campaigns).

You're right that there are big differences. I'm inclined to agree that some asks should be an "easier sell" too. I'm wondering if you think that these differences notably affect the arguments of this post?

I think potentially they do, in terms of the typical playbook and framing for corporate campaigns being less relevant. As in, it's less moral outrage vs. profit and appealing to corporations to be good, and more reckless endangerment vs. naive optimism and appealing to people at corporations (who presumably care about their own safety) to see sense. Morality/ethics doesn't need to be a factor, assuming people care for their own lives and those of their family and friends.

Yeah, that's my petition, which is still only on 41 :( Anyone want to help me get more signatures? Really it would be quite a poor showing not to get over the 10,000 mark needed for a government response before the UK AI Safety Summit on Nov 1-2.