Effective Ventures (EV) is a federation of organisations and projects working to have a large positive impact in the world. EV was previously known as the Centre for Effective Altruism but the board decided to change the name to avoid confusion with the organisation within EV that goes by the same name.

EV Operations (EV Ops) provides operational support and infrastructure that allows effective organisations to thrive.

Summary

EV Ops is a passionate and driven group of operations specialists who want to use our skills to do the most good in the world.

You can read more about us at https://ev.org/ops.

What does EV Ops look like?

EV Ops began as a two-person operations team at CEA. We soon began providing operational support for 80,000 Hours, EA Funds, the Forethought Foundation, and Giving What We Can. And eventually, we started supporting newer, smaller projects alongside these, too.

As the team expanded and the scope of these efforts increased, it made less sense to remain a part of CEA. So at the end of last year, we spun out as a relatively independent organisation, known variously as “Ops”, “the Operations Team”, and “the CEA Operations team”.

For the last nine months or so, we’ve been focused on expanding our capacity so that we can support even more high-impact organisations, including the GovAI, Longview Philanthropy, Asterisk, and Non-trivial. We now think that we have a comparative advantage in supporting and growing high-impact projects — and are happy that this new name, “Effective Ventures Operations”' or “EV Ops”, accords with this.

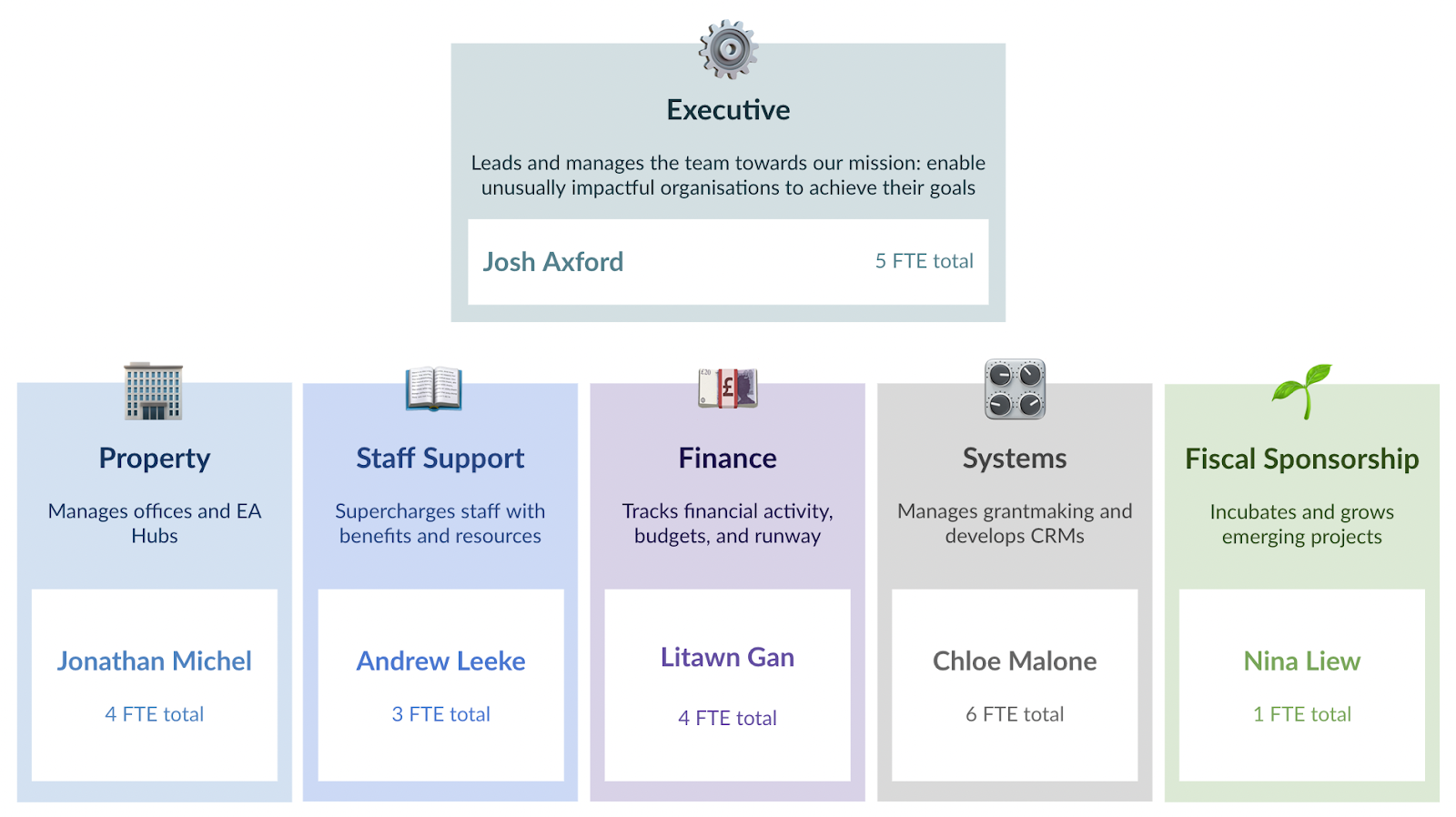

EV Ops is arranged into the following six teams:

The organisations EV Ops supports

We now support and fiscally sponsor several organisations (learn more on our website). Alongside these we support a handful of Special Projects: smaller, 1-2 person, early-stage projects which may grow into independent organisations of their own.

We’re keen to support a wide range of projects looking to do good in the world, although we’re close to current capacity. To see if we could help your project grow and develop, visit https://ev.org/ops/about or complete the expression of interest form.

Get involved

We’re currently hiring for the following positions:

- Project Manager for Oxford EA hub

- Senior Bookkeeper / Accountant

- Operations Associate

- Executive Assistant for the Property team

- Operations Associate - Salesforce Admin

- Finance Associate

If you’re interested in joining our team, visit https://ev.org/ops/careers.

If you have any questions about EV or EV Ops, just drop a comment below. Thanks for reading!

What are your criteria for deciding which organizations to support?

I’m particularly interested in how you think about cause prioritization in this process. The list of currently supported organizations looks roughly evenly split between organizations that are explicitly longtermist (e.g. Forethought Foundation and Longview Philanthropy) and organizations that (like the EA community as a whole) support both longtermist and neartermist work (e.g. GWWC and EA Funds). I don’t see any that focus solely on neartermist work. Do you expect the future mix of supported organizations to look similar to the current one? Would an organization working on animal welfare be as likely to receive support as one working on biosecurity if other factors like strength and size of team were the same?

Also, I’ve mentioned this elsewhere, but I really hope this change leads to a major reassessment of how governance is structured for these organizations.