Since writing The Precipice, one of my aims has been to better understand how reducing existential risk compares with other ways of influencing the longterm future. Helping avert a catastrophe can have profound value due to the way that the short-run effects of our actions can have a systematic influence on the long-run future. But it isn't the only way that could happen.

For example, if we advanced human progress by a year, perhaps we should expect to see us reach each subsequent milestone a year earlier. And if things are generally becoming better over time, then this may make all years across the whole future better on average.

I've developed a clean mathematical framework in which possibilities like this can be made precise, the assumptions behind them can be clearly stated, and their value can be compared.

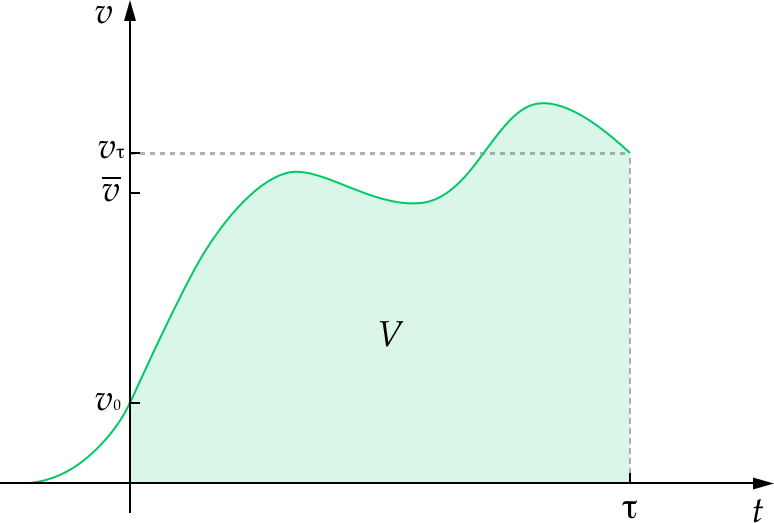

The starting point is the longterm trajectory of humanity, understood as how the instantaneous value of humanity unfolds over time. In this framework, the value of our future is equal to the area under this curve and the value of altering our trajectory is equal to the area between the original curve and the altered curve.

This allows us to compare the value of reducing existential risk to other ways our actions might improve the longterm future, such as improving the values that guide humanity, or advancing progress.

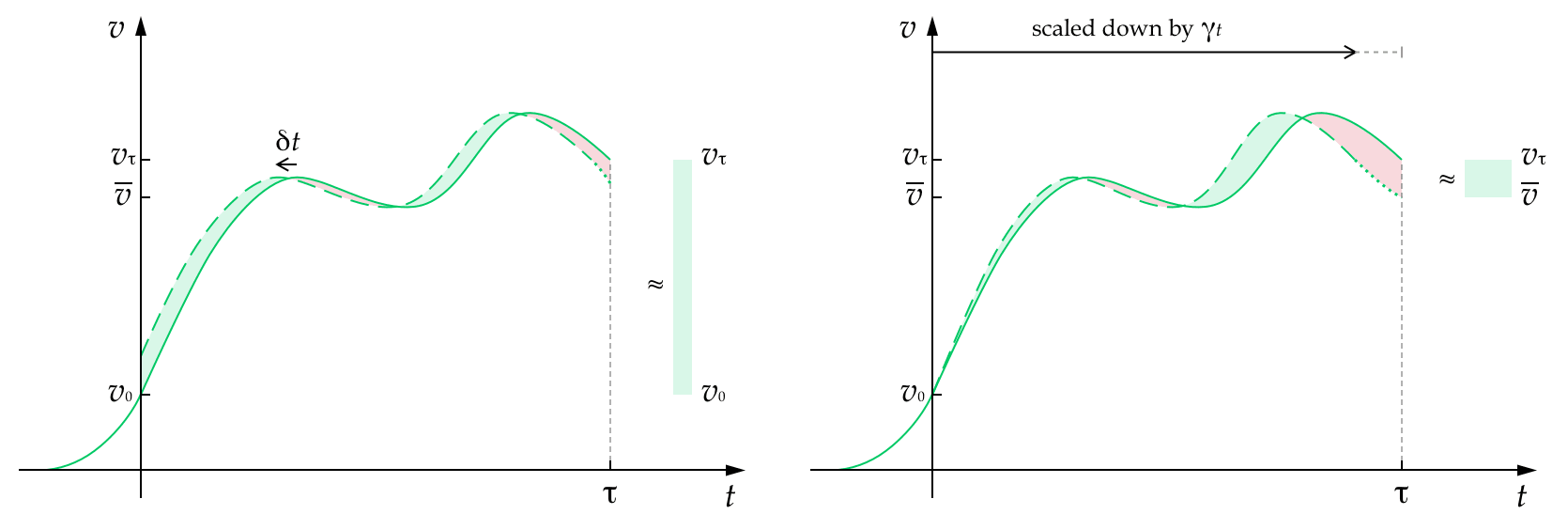

Ultimately, I draw out and name 4 idealised ways our short-term actions could change the longterm trajectory:

- advancements

- speed-ups

- gains

- enhancements

And I show how these compare to each other, and to reducing existential risk.

My hope is that this framework, and this categorisation of some of the key ways we might hope to shape the longterm future, can improve our thinking about longtermism.

Some upshots of the work:

- Some ways of altering our trajectory only scale with humanity's duration or its average value — but not both. There is a serious advantage to those that scale with both: speed-ups, enhancements, and reducing existential risk.

- When people talk about 'speed-ups', they are often conflating two different concepts. I disentangle these into advancements and speed-ups, showing that we mainly have advancements in mind, but that true speed-ups may yet be possible.

- The value of advancements and speed-ups depends crucially on whether they also bring forward the end of humanity. When they do, they have negative value.

- It is hard for pure advancements to compete with reducing existential risk as their value turns out not to scale with the duration of humanity's future. Advancements are competitive in outcomes where value increases exponentially up until the end time, but this isn't likely over the very long run. Work on creating longterm value via advancing progress is most likely to compete with reducing risk if the focus is on increasing the relative progress of some areas over others, in order to make a more radical change to the trajectory.

The work is appearing as a chapter for the forthcoming book, Essays on Longtermism, but as of today, you can also read it online here.

Existential risk, and an alternative framework

One common issue with “existential risk” is that it’s so easy to conflate it with “extinction risk”. It seems that even you end up falling into this use of language. You say: “if there were 20 percentage points of near-term existential risk (so an 80 percent chance of survival)”. But human extinction is not necessary for something to be an existential risk, so 20 percentage points of near-term existential risk doesn’t entail an 80 percent chance of survival. (Human extinction may also not be sufficient for existential catastrophe either, depending on how one defines “humanity”))

Relatedly, “existential risk” blurs together two quite different ways of affecting the future. In your model: V=¯vτ. (That is: The value of humanity's future is the average value of humanity's future over time multiplied by the duration of humanity's future.)

This naturally lends itself to the idea that there are two main ways of improving the future: increasing ¯v and increasing τ.

In What We Owe The Future I refer to the latter as “ensuring civilisational survival” and the former as “effecting a positive trajectory change”. (We’ll need to do a bit of syncing up on terminology.)

I think it’s important to keep these separate, because there are plausible views on which affecting one of these is much more important than affecting the other.

Some views on which increasing ¯v is more important:

Some views on which increasing τ is more important:

What’s more, changes to τ are plausible binary, but changes to ¯v are not. Plausibly, most probability mass is on τ being small (we go extinct in the next thousand years) or very large (we survive for billions of years or more). But, assuming for simplicity that there’s a “best possible” and “worst possible” future, ¯v could take any value between 100% and -100%. So focusing only on “drastic” changes, as the language of “existential risk” does, makes sense for changes to τ, but not for changes to ¯v .

I think this is a useful two factor model, though I don't quite think of avoiding existential risk just as increasing τ. I think of it more as increasing the probability that it doesn't just end now, or at some other intermediate point. In my (unpublished) extensions of this model that I hint at in the chapter, I add a curve representing the probability of surviving to time t (or beyond), and then think of raising this curv... (read more)