Katja Grace, 8 March 2023

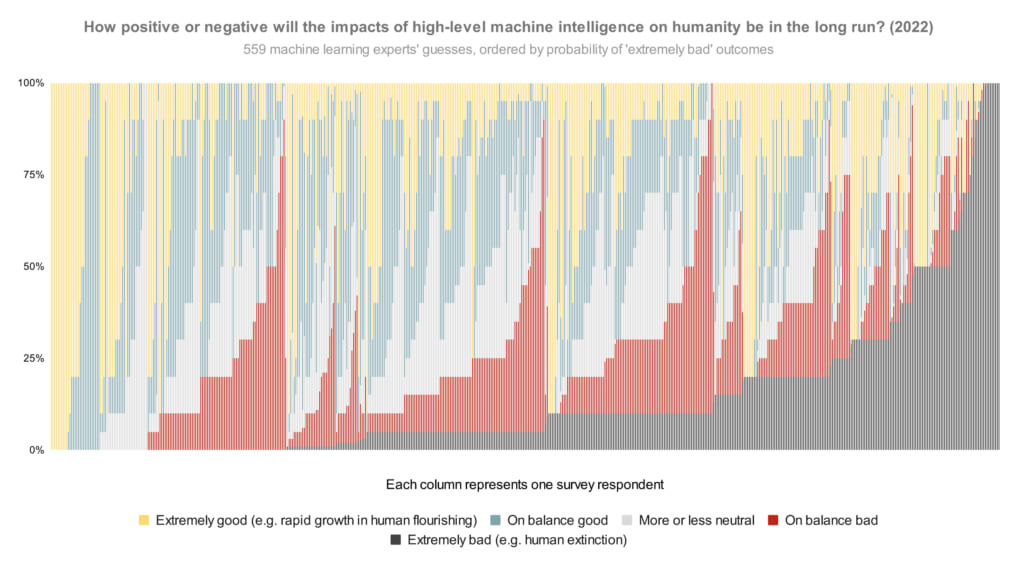

In our survey last year, we asked publishing machine learning researchers how they would divide probability over the future impacts of high-level machine intelligence between five buckets ranging from ‘extremely good (e.g. rapid growth in human flourishing)’ to ‘extremely bad (e.g. human extinction).1 The median respondent put 5% on the worst bucket. But what does the whole distribution look like? Here is every person’s answer, lined up in order of probability on that worst bucket:

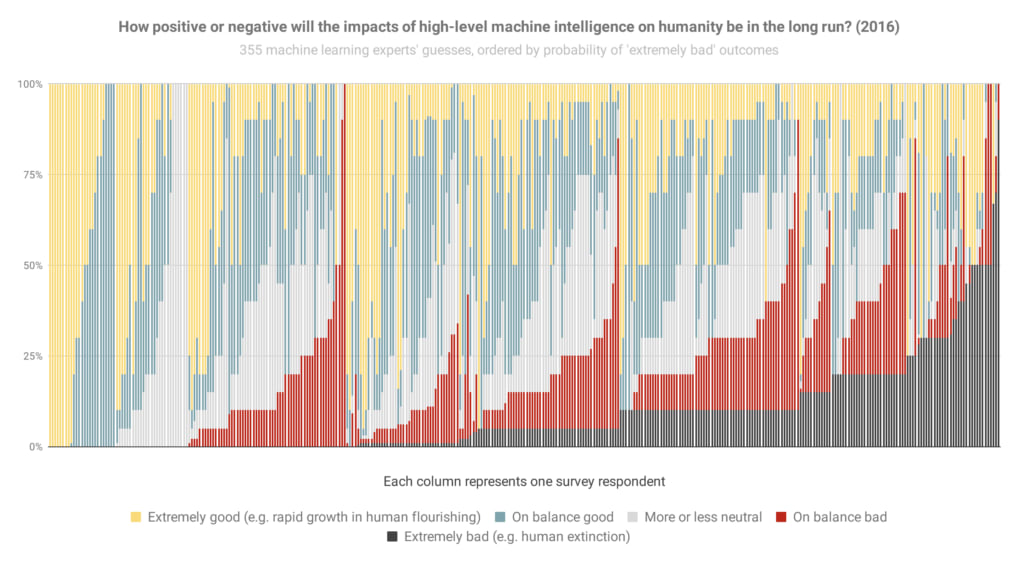

And here’s basically that again from the 2016 survey (though it looks like sorted slightly differently when optimism was equal), so you can see how things have changed:

The most notable change to me is the new big black bar of doom at the end: people who think extremely bad outcomes are at least 50% have gone from 3% of the population to 9% in six years.

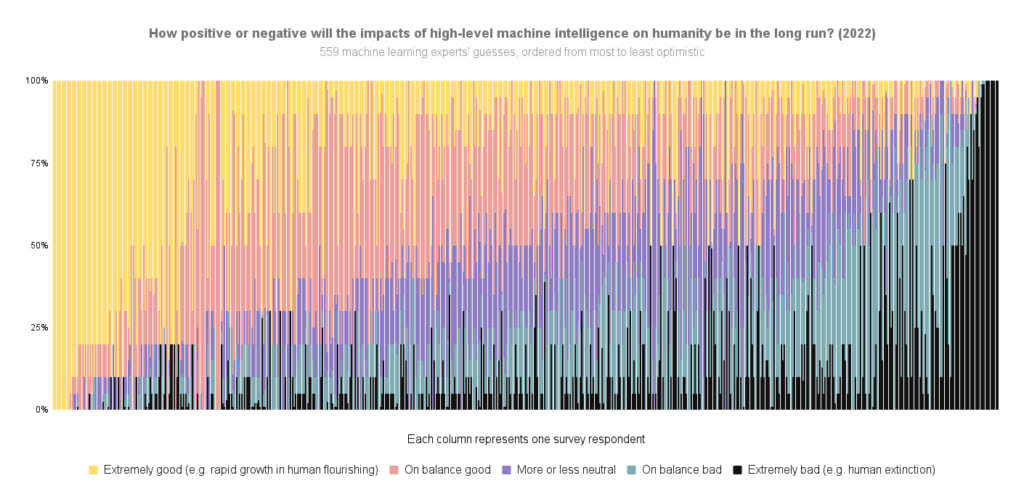

Here are the overall areas dedicated to different scenarios in the 2022 graph (equivalent to averages):

- Extremely good: 24%

- On balance good: 26%

- More or less neutral: 18%

- On balance bad: 17%

- Extremely bad: 14%

That is, between them, these researchers put 31% of their credence on AI making the world markedly worse.

Some things to keep in mind in looking at these:

- If you hear ‘median 5%’ thrown around, that refers to how the researcher right in the middle of the opinion spectrum thinks there’s a 5% chance of extremely bad outcomes. (It does not mean, ‘about 5% of people expect extremely bad outcomes’, which would be much less alarming.) Nearly half of people are at ten percent or more.

- The question illustrated above doesn’t ask about human extinction specifically, so you might wonder if ‘extremely bad’ includes a lot of scenarios less bad than human extinction. To check, we added two more questions in 2022 explicitly about ‘human extinction or similarly permanent and severe disempowerment of the human species’. For these, the median researcher also gave 5% and 10% answers. So my guess is that a lot of the extremely bad bucket in this question is pointing at human extinction levels of disaster.

- You might wonder whether the respondents were selected for being worried about AI risk. We tried to mitigate that possibility by usually offering money for completing the survey ($50 for those in the final round, after some experimentation), and describing the topic in very broad terms in the invitation (e.g. not mentioning AI risk). Last survey we checked in more detail—see ‘Was our sample representative?’ in the paper on the 2016 survey.

Here’s the 2022 data again, but ordered by overall optimism-to-pessimism rather than probability of extremely bad outcomes specifically:

For more survey takeaways, see this blog post. For all the data we have put up on it so far, see this page.

See here for more details.

Thanks to Harlan Stewart for helping make these 2022 figures, Zach Stein-Perlman for generally getting this data in order, and Nathan Young for pointing out that figures like this would be good.

"Yet they carry on doing what they're doing, despite knowing the risks. Perhaps they're motivated by curiosity, hubris, wealth, fame, status, or prestige. (Aren't we all?) Perhaps these motives overwhelm their moral qualms about what they're doing."

I'd like to add inertia/comfort to this list: people don't like to change jobs, and changing fields is much harder.

Intervention idea: offer capabilities researchers support to transition out of the field