I’m looking for some feedback. I’ve done some modeling to see how giving at death compare compares to giving during life. I’ve looked specifically at giving 10% of annual salary versus giving a certain percentage of net worth at death. Based on the models that I’m looking at, giving 10% of annual salary is less effective than giving 10% of net worth at death if the population of givers is 750,000 or more. There is no parameter at which the annual givers outperform the givers at death. I would like to hear any feedback so that I can see if my model holds up to scrutiny.

Should altruists give during life or at death?

A mathematical & ethical exploration

📋 The question:

If altruists donated a percentage of their income during life (e.g., 10% annually) versus donating a percentage of their net worth at death (e.g., 10–50%), which approach is more effective — especially at the population level?

🔷 Key findings from modeling a realistic, steady-state population:

We simulated a population of altruists (1M–10M people), with realistic wealth accumulation, mortality, and giving behaviors.

Even though only ~1% of people die each year, their accumulated net worth at death is so much larger than annual income that total donations from death-based giving outperformed life-based giving — starting in year 1 and continuing indefinitely.

📊 Results (1M altruists, steady-state, average annual donations):

Strategy | Average annual donations |

| 10% of income (everyone) | $5B |

| 50% of net worth at death (everyone) | $65.8B |

| 40% of net worth at death (everyone) | $52.6B |

| 30% of net worth at death (everyone) | $39.5B |

| 20% of net worth at death (everyone) | $26.3B |

| 10% of net worth at death (everyone) | $13.1B |

Even donating just 10% of net worth at death generated more than 2× the annual donations of giving 10% of income during life.

And at 50% of net worth at death, donations were over 13× higher than giving 10% of income annually.

🌍 Real-world context:

- About 150,000 people worldwide die each year with >$2M in net worth.

- Together, they hold $750B–$1T at death.

- If they gave just 50% at death, it would add $375–500B/year to global giving — roughly half of all current global philanthropy (~$900B/year) — without giving anything during life.

📈 Why death-based giving is even more powerful:

- If individuals stopped giving during life and allowed their full income & wealth to compound, their estates at death would grow much larger — making their death-based donations even greater than today’s models assume.

⚖️ What about moral and practical arguments for giving during life?

People often justify giving during life to:

- Respond to immediate crises

- Support interventions with compounding social impact

- Feel moral satisfaction & signal values

However, at the population level, the steady flow of net worth at death donations already surpasses lifetime giving and is more than enough to meet urgent and ongoing needs — even starting in year 1.

🔷 Final insight:

If altruists gave even just 10% of their net worth at death, they would out-donate what they currently achieve by giving 10% of their income during life.

If they gave 50% of net worth at death, their donations would be more than 13× greater — while also keeping their full income and wealth throughout life.

TL;DR:

Giving 10% of income during life feels morally satisfying, but at the population level, giving 10–50% of net worth at death generates far more resources, meets urgent needs, and allows wealth to grow — making it the more effective strategy overall.

Just noting that there's a huge literature on this exact question, eg

I’m skimming but so far I’m surprised how qualitative the arguments are and how they seem to look at it at an individual level vs a population of altruists. Thanks!

Thank you. I was hoping there was!

#2 is what changed my mind a few years ago. An index fund might give me 7% annual returns, but I suspect that investing in ridding a village of malaria has a much higher ROI, just not for me. The model would've been much stronger if it had included this effect of increasing others' resources.

Maybe I’m not following, but if there was a general consensus and coordination (easier said than done) for giving at the end, there would be frequent enough giving by the die-ers that it mathematically eclipses the consistent giver model… at least that’s what I saw and am asking about.

I don't see the report considering the growth of money in recipients' pockets. It treats giving like throwing money into a black hole, not as another investment with returns.

To put it concretely, let's say person A is in the global top 5% income wise and person B is below the poverty line. Person A (most on this forum) can then choose to invest their money, grow it and give at death.

Let's ignore risk of value drift and say you manage to grow it 7% annually. That's nice, but instead giving it away means person B can

All of these things make the money grow in person B's pockets as well. My prior (medium epistemic status) is that this growth trumps the 7% an index fund can offer. I argue that after 60-odd years of compounding - most EAs are young and healthy - person B has more than they would've if they got the money all in one lump sum from person A at death.

So this model only considers the resources of person A at death, when what we really care about is the resources of persons A and B combined.

In a population of givers, if the flow of donations is higher with one va the other paradigm, the effects on B are greater. Right?

Because in a sufficiently large enough population of givers, there are people dying constantly. So it’s just a matter of mathematically modeling it out to see what the optimized wait time is. I’m not sure about the inflation part, anybody that invest has to invest against inflation, but still chooses to invest their money as opposed to spending it all now.

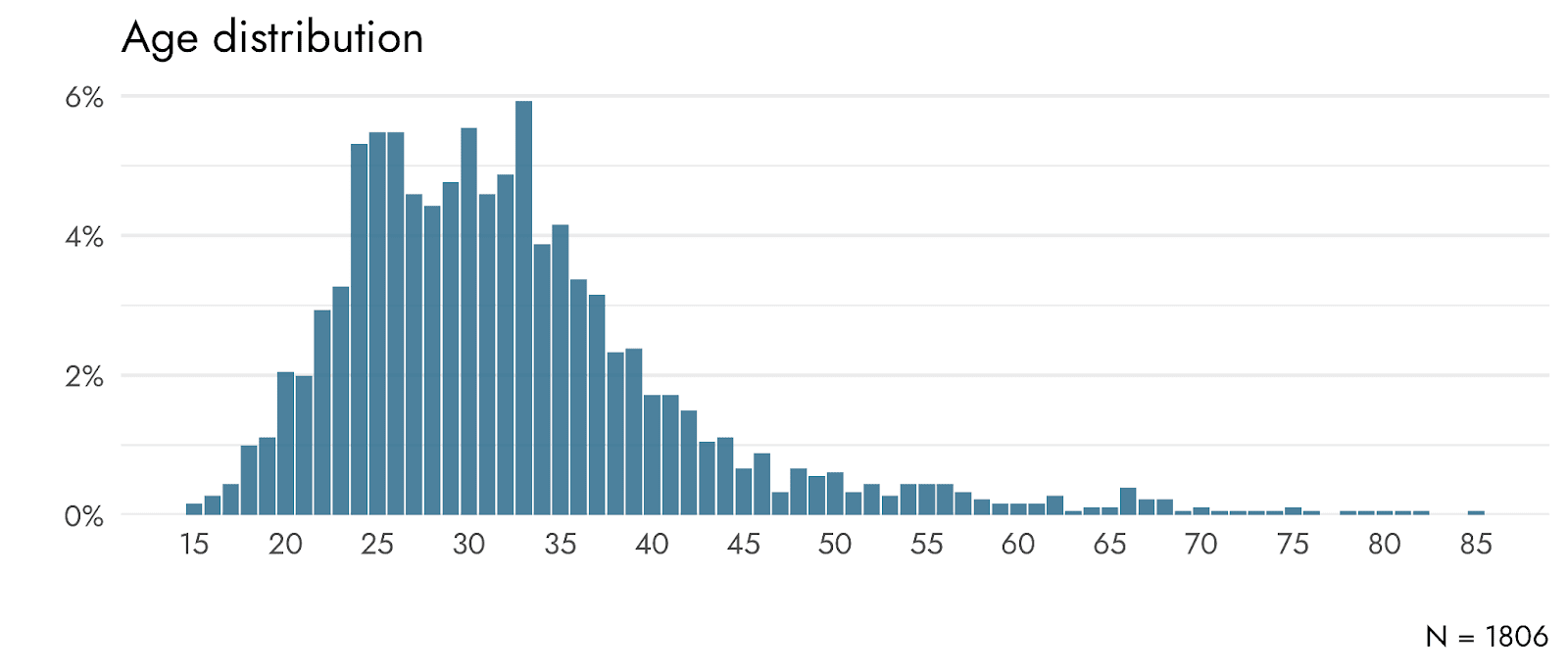

EAs are a relatively young population, with a lot of years before most will die naturally. From the EA Survey: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/z4Wxd2dnTqDmFZrej/ea-survey-2024-demographics#Age

Many EAs also believe that this may be "the most important century", and that many pivotal decisions (e.g. around AI) will happen within the next few years or decades rather than being just as influenceable in 2080 or so.

That may be a hurdle for sure and may make my model idealistic. I wonder how charitable the 45 and overs are regardless of whether they identify as EA or not

I ran the numbers based on this exact population distribution and count. It’s a relatively small population and I think it misrepresents the world population of charitable people, but in any event, if you have <2k people who skew young, you’d want to ease into the shift towards donating at death to cover the first few decades, but once the pump is primed you’ll be able to go full death and outpace.

Simulated Giving Strategy for Young-Skewed Altruist Population

We modeled 1,806 altruists with a young-skewed age distribution (mostly 20-40). The strategy

combines modest lifetime giving with significant giving at death:

- Early career (20-40): donate ~7.5% of income.

- Mid career (40-60): donate ~2.5% of income.

- At death: donate 50% of net worth.

Results over 100 years (in billions USD):

Decade Income Donations Death Donations Pooled Wealth

10 0.07 0.05 0.95

20 0.05 0.14 3.29

30 0.03 0.24 7.74

40 0.02 0.47 15.13

50 0.02 0.60 27.09

60 0.02 3.25 41.20

70 0.03 6.90 51.47

80 0.04 5.40 58.51

90 0.04 2.36 66.34

100 0.03 2.57 75.04

Key insights:

- Income donations provide immediate but modest support.

- Death donations grow over time and ultimately surpass income-based giving.

- The pooled wealth of the population continues to grow, providing future security and flexibility.A hybrid strategy balances urgent needs today and maximizes long-term impact.

Could you please share what assumptions are in the simulation? It's hard to learn from this or give feedback otherwise.

It’s based on giving 10% of your salary annually versus 10% of your net worth at death, assuming average distribution of ages, income levels, normal investing habits, but I don’t have any more granular detail, happy for anybody who knows more than I do to flesh it out or pick at !

Your key rebuttal to the pro-giving-sooner arguments appears to be the finding that a "give at death" policy would lead to higher annual donations in a population of effective altruists, even in year 1. I can see others are questioning whether this claim is actually true, but I think this is missing the point. I think even if this claim is true, it is not relevant.

The question that each individual donor needs to answer is: What is the marginal impact of donating money now vs investing it and then donating it at some later time? (for each possible later time they could donate, which could even be after their death) I don't think the finding of your simulation actually has any bearing on this question.

This is because your finding is clearly highly dependent on mortality statistics. For example, if the variance in life-expectancy were lower so that no one died in the next 5 years, then the finding that donations are higher even in year 1 would no longer hold. On the other hand, the question of when a given donation will have the highest marginal impact has nothing to do with mortality statistics among effective altruists. So the two questions shouldn't have anything to do with each other.

If you are finding that one policy is leading to more wealth being moved than another (even after accounting for gains from interest), then I think you are also advocating a change in how much people should give, not just a change in when what they give should be given.

People can always give annually and donate a significant chunk of their wealth at death.

Sure you could posit what would happen if nobody died but you could also posit what would happen if the value of money suddenly dropped to zero. People do die and in a large enough population this is predictable. In my model, the population of 750k people with a real world based age distribution did the trick.

What is the appropriate gauge of the effectiveness of a giving strategy if it’s not how much wealth is being moved? Yes I’m advocating for giving more but 1. It’s after you’re done enjoying it, which for a lot of people is the main reason for not giving in the first place, which should alienate less people and make the argument about the EA population skewing young less of a problem, and 2. If you have more wealth because you invested, you have more to give and more left over (for inheritance in my model). Yes you can give during life and at death. The reason I tried to model 10% of annual income vs. 10, 20… 50% at death was to see how many conventionally selfish people could be brought into the fold, have their cake during life and eat their guilt away with their death giving and have the amount of money donated in the population per unit time be the same or better. I’m definitely having trouble understanding any argument that doesn’t directly address money donated in the population over time.

So I think you're trying to make two points at once (the points 1 and 2 as you've defined them) and that has prompted a bit of a negative reaction because most people responding (including me) are focusing on point 2, which is a well worn argument in EA circles that you seemed to be making an overly strong claim about.

To state it more clearly, I think most people have interpreted you as claiming:

"If you have X dollars that you want to donate, then it is better to invest them, and donate the X dollars + investment returns at death, than to donate the X dollars immediately"

Whereas what you are actually claiming is:

"The policy 'give X% at death' is an easier sell than the policy 'give Y% of your income each year', even when X is significantly bigger than Y, and in a realistic population of givers could result in more wealth being moved in total, even in year 1."

Do you agree with that summary?

If so, I think that's an interesting claim, and I'm sorry that a lot of us have been thrown off by the phrasing! My concerns with this claim would be:

I think there is a psychological and messaging discussion that flows from this, but I want people to poke at it for sure, and I’m feeling like population based analysis is more in line with EA than individual analysis.

Closer! Without the psychology and even when comparing 10% of annual income vs 10% of net worth at death, in a population of 750k givers that represent a normal distribution of ages and normal death rates, giving 10% net worth at death produces more donated dollars per year (even in year 1) versus giving 10% of income.

It's still a psychology question! The people who die in year 1 and make up those increased donations haven't had time to accrue interest, so they're donating money you claim they'd never have donated if they were only 10% per year pledgers, which is a claim about donor psychology, and an unrealistic one at that!

I think most people are saving investing for life so I think I’m looking at it in more of a real world population than in a vacuum

Afaict the model doesn't apply well to effective altruists as a sub-population.

Most EAs are young, and unless the movement suddenly becomes popular among older people, few are likely to die in the next 40 years[1]. Even if you fully buy this type of argument, and you believe donation opportunities are roughly uniformly distributed over time, the members of the community should probably do some 'donation smoothing' while alive.

(If there’s an existential catastrophe, donating at death won’t matter anyway.)

Ok so is that the only weakness you see in the model? If so, what if we look at the entire population of donators, rather than the “EA population”. Or just do the “smoothing”? My question just has to do with pure effectiveness

I don't think it's specifically about the EA population.

The value of donations may change over time. Your model shows that investing results in having more money to donate in the future. But it doesn't seem to take into account the value of that money (or the value of what the money can buy). This might change over time.

A couple of examples:

Those are cases where the value of the donation declines. There could be other cases where the value of donation increases - perhaps as a result of new research showing how resources can be used more effectively, or a new treatment etc. In this case, there would be more money in the future (due to returns on investment) and more cost-effective things to spend this money on.

I think we’re people seem to be getting tripped up with this is that everybody is not doing one thing or another in the sense that if everybody is giving at death, there is a steady stream of people dying so there is giving happening all the time. Does that make sense?

No, I don't understand your point. The fact that some people are dying and donating now doesn't answer the question of whether people who are not dying now should donate or invest now.

If there is a population of let’s say 10 million people that are donators, then there is a certain amount of money per unit time that is being donated. To the recipients of the donation, it would matter less the individual behavior is than the behavior of the population is. So if there is a model whereby holding onto one’s wealth (and being motivated to grow it and enjoy it) results in more money per unit time donated within the population, that would seem to be more effective to me. So , assuming some sort of coordination or at least consensus about the best way to give, is based on not just that one person

This is still only considering the amount of money donated, not the value of what the money can buy.

I think we may be going round and round. The amount is related to the value by some constant, unless you’re implying a time factor, but as far as I can see, the timing concern is a red herring, as in my model the pump is already primed and wealthy enough donors are dying in week one.

Yes, I and others have explicitly been saying time is a factor, e.g. see my 2 examples above and comments by others. The amount is likely not related to value by some constant. The value that a given amount of money can buy will vary over time.

I'll be honest, I don't understand this point, or why it means the value of a donation won't change over time.

I may just be misunderstanding. But I don't think there's much more to say on this, unless e.g. you're able to share your model on Excel or Google sheets.

(I haven't looked deeply into the model.)

One thing is that 'donations at death' are likely qualitatively different to 'donations during life'. This difference might be important in terms of how effective/desirable the individual donations are.

Can you elaborate a little bit? I wanna see what your saying.

Currently, I'd expect older people to donate less to animal welfare than younger people. In the future, the way donation patterns differ might change. But there might be some differences that stay consistent over time, e.g. older people donating in a more/less risk-averse manner.

I didn’t take that into account! So yeah we have to factor in an assumption that the more we advance the average age of the giver, the less progressive the causes, with a bit of “lag” expected, for better or worse!

After some time & querying Gemini 3 I adjusted my thinking on this a bit, I wonder if others may benefit from this info.

Due to personal circumstances & certain tax implications I think a good strategy for me is to max out a traditional IRA with 100% equities every year & keep any donations I would make in year in a 100% equities standard investment account so I can batch together donations in certain years & get a better tax deduction.

100% Equities

In standard personal finance, you lower risk as you age to protect your retirement security. In "Investing to Give," the philosophy is different.

Because large charities and global problems are less vulnerable to market volatility than a single individual, many EAs advocate for a risk-neutral or high-equity portfolio.

* The Logic: If the market crashes 20%, a large charity (like the Against Malaria Foundation) will not "go bust" the way an individual retiree might. They can wait for the market to recover.

* The Portfolio: This usually points toward 100% broad-market equities (like a Total World Stock Market Index Fund). You accept higher volatility for higher expected long-term returns, maximizing the final donation amount.

Traditional IRA

For "Giving Later," Traditional IRAs/401(k)s are often superior to Roths if you plan to donate the account itself upon death or use it for distributions in old age.

* Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs): Once you reach age 70½, you can transfer up to $105,000+ (indexed for inflation) per year directly from a Traditional IRA to a charity. This counts toward your Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) but does not count as taxable income. This is usually more tax-efficient than withdrawing the money (taking the income hit) and then donating it.

* Beneficiary Designation (The "Death Tax" Hack): If you die with unspent assets, leaving a Traditional IRA to heirs is inefficient (they pay income tax on it). If you leave the Traditional IRA to a charity as the beneficiary, the charity receives 100% of the money tax-free. Leave your Roth assets (which are tax-free) to your human heirs.

I also happen to have specific health conditions with higher risk of disability. If I invest money in a traditional IRA it has extra optionality. If I am relatively healthy & don’t need it, then I can donate it in older age. If I suffer a bad health incident that prevents me from working more then I can use some of it for myself.

Standard Investment Account Batched Donations

Because I live in a US state with no state income tax to deduct, my "baseline" itemized deductions are likely very low (perhaps just mortgage interest, if I have any). This makes the "Standard Deduction hurdle" much harder to clear, meaning my smaller annual donations often yield zero tax benefit.

Here is how to solve that with “Batching".

Part 1: The "Batching" Strategy

The Goal: Stop giving small amounts every year where you get no tax credit. Instead, save up and give a massive amount in one single year to crush the Standard Deduction, then give nothing (on paper) for the next few years.

The Math (2025/2026 Projections):

* Single Standard Deduction: ~$15,000

* Married Standard Deduction: ~$30,000

Scenario: Let's assume you are Single and want to donate $5,000/year.

* The "Standard" Way: You donate $5k in 2025, 2026, 2027, & 2028.

* Total Donated: $20,000

* Total Tax Deduction: $0 (because $5k is less than the $15k standard deduction; you just take the standard deduction every year anyway).

* The "Bunching" Way: You save that money in an investment account for 4 years, then donate all $20,000+appreciation in Year 4.

* Year 1-3: You take the Standard Deduction.

Year 4: You donate $20,000+ through direct stock transfers. Combined with other deductions (e.g., sales tax, mortgage interest), you might reach $25,000+ in itemized deductions. For a single tax filer making $100,000 a year this would mean saving an extra $2000+ in taxes**.

Donation Deduction Limits

The amount you can deduct in a single year is subject to limitations based on your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

• For gifts of appreciated long-term capital gain property (like stock) to a public charity (including Donor Advised Funds), the deduction is generally limited to 30% of your AGI.

• Any amount exceeding this limit can usually be carried forward for up to five additional tax years.

Here’s an even better write-up of this & similar ideas

https://michaelgris.com/posts/charity-tax/

There are tax reasons & annual donation multiplier reasons like employee donation matching or matching events or credit card incentives, that make donating some percent each year of life make more sense.

Any rough quantification? If I live my life as a non altruist, build a net worth of 10 million dollars and give 5 million away at death and am part of a population of people who, instead of giving a little here and there or giving 10% of annual salary, just build wealth, buy cars, buy a home or two, take vacations, live capitalistically but with some smug consolation that they’re going to leave half to their kids and half to effective charities, the math that I’m seeing (and showed) is that if that population is >750k, donations will be higher immediately and continue to outpace a similar financial population that does 10% annually. Plenty of assumptions and simplifications in the model.

By “make more sense” I mean like change the calculations to be more positive for, but still uncertain on the broader decision of give now vs. invest.

Like I’d assume one could at least 2X their annual donations with these things. So for someone using these strategies the give now argument should be 2X stronger for the sum of donations they can multiply now that they can’t multiply in the future.

It seems obvious on the face of it that saving until you die will leave you the most to give to charity. But this discounts the benefits of having that money earlier for the recipient.

I’m trying to understand why that’s true at a population level, as people in a large enough population are dying now (assuming we have enough older altruists in the cohort).

I think the logic of the article is assuming the your money accrues compound interest only if you hold on to it. But if you give that money to someone else, they too can put it in the bank and accrue interest, the fact that they do something different with it (like staying alive) suggests there is something more valuable in that choice. Before putting money in the bank we often invest in ourselves, like paying for a tertiary education for instance, and that itself pays off more than that money would in the bank. The same logic stands for the person someone donates to. For instance I'm currently paying for a friend's daughter in Africa to go through medical school, that's costing me money now that will result in her supporting her wider family for an entire generation before I die. Their family might be self-sufficient by that time.

I don't think there's a meaningful distinction between this situation on an individual level or a population level. If everyone gives at death, then a huge amount of money that could have been given earlier and could have accrued out-weighed benefits for the recipients stays with the wealthy, and those potential recipients die or fail to benefit from having the money earlier.

I understand what you’re saying but if the norm was to build and enjoy wealth and give when you’re gone, there is no “earlier”. It’s a flow of money within and between populations. Now there is the question of whether there is more wealth building if more vs less people have it over a single lifetime. I’m interested in where all of these “sweet spots” are and converge.

I'm not sure that's how time works, I don't see that scaling makes any difference.

If wealth-building wasn't just wealth-hoarding (which is the most lucrative way of wealth building that we have at present - see Thomas Piketty r>g) this might be a worthwhile approach—thinking about who is a better steward of the investment (I think an excess of paternalism might be playing a part in this assessment) but wealth-hoarding results in greater inequality, which is what we're trying to avoid, surely, with charitable giving.

I agree though that there is probably a sweet-spot.