This is the summary of the report with additional images (and some new text to explain them) The full 90+ page report (and a link to its 80+ page appendix) is on our website.

Summary

This report forms part of our work to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses of interventions and charities based on their effect on subjective wellbeing, measured in terms of wellbeing-adjusted life years (WELLBYs). This is a working report that will be updated over time, so our results may change. This report aims to achieve six goals, listed below:

1. Update our original meta-analysis of psychotherapy in low- and middle-income countries.

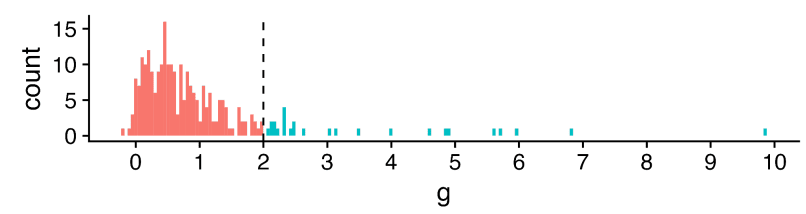

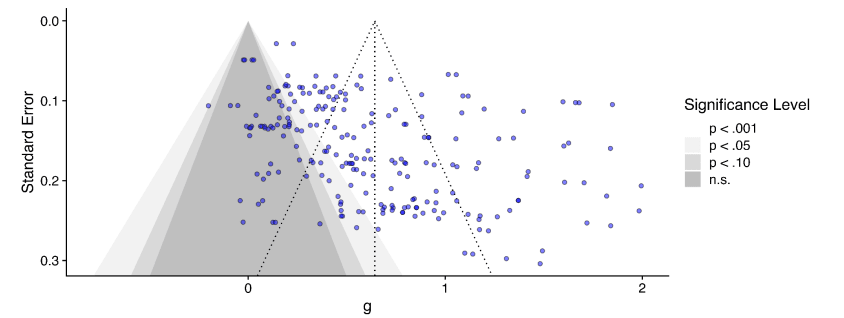

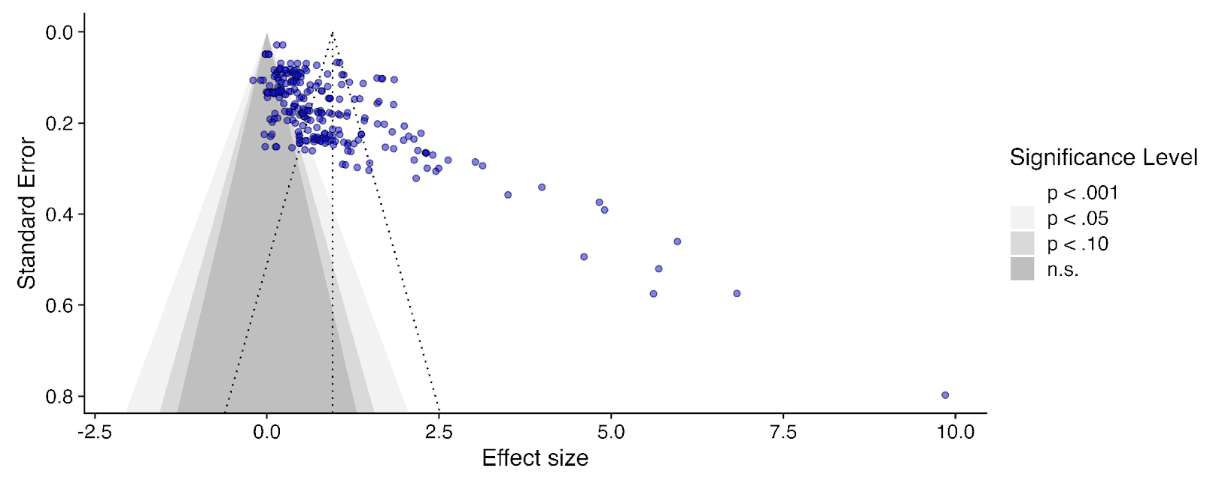

In our updated meta-analysis we performed a systematic search, screening and sorting through 9390 potential studies. At the end of this process, we included 74 randomised control trials (the previous analysis had 39). We find that psychotherapy improves the recipient’s wellbeing by 0.7 standard deviations (SDs), which decays over 3.4 years, and leads to a benefit of 2.69 (95% CI: 1.54, 6.45) WELLBYs. This is lower than our previous estimate of 3.45 WELLBYs (McGuire & Plant, 2021b) primarily because we added a novel adjustment factor of 0.64 (a discount of 36%) to account for publication bias.

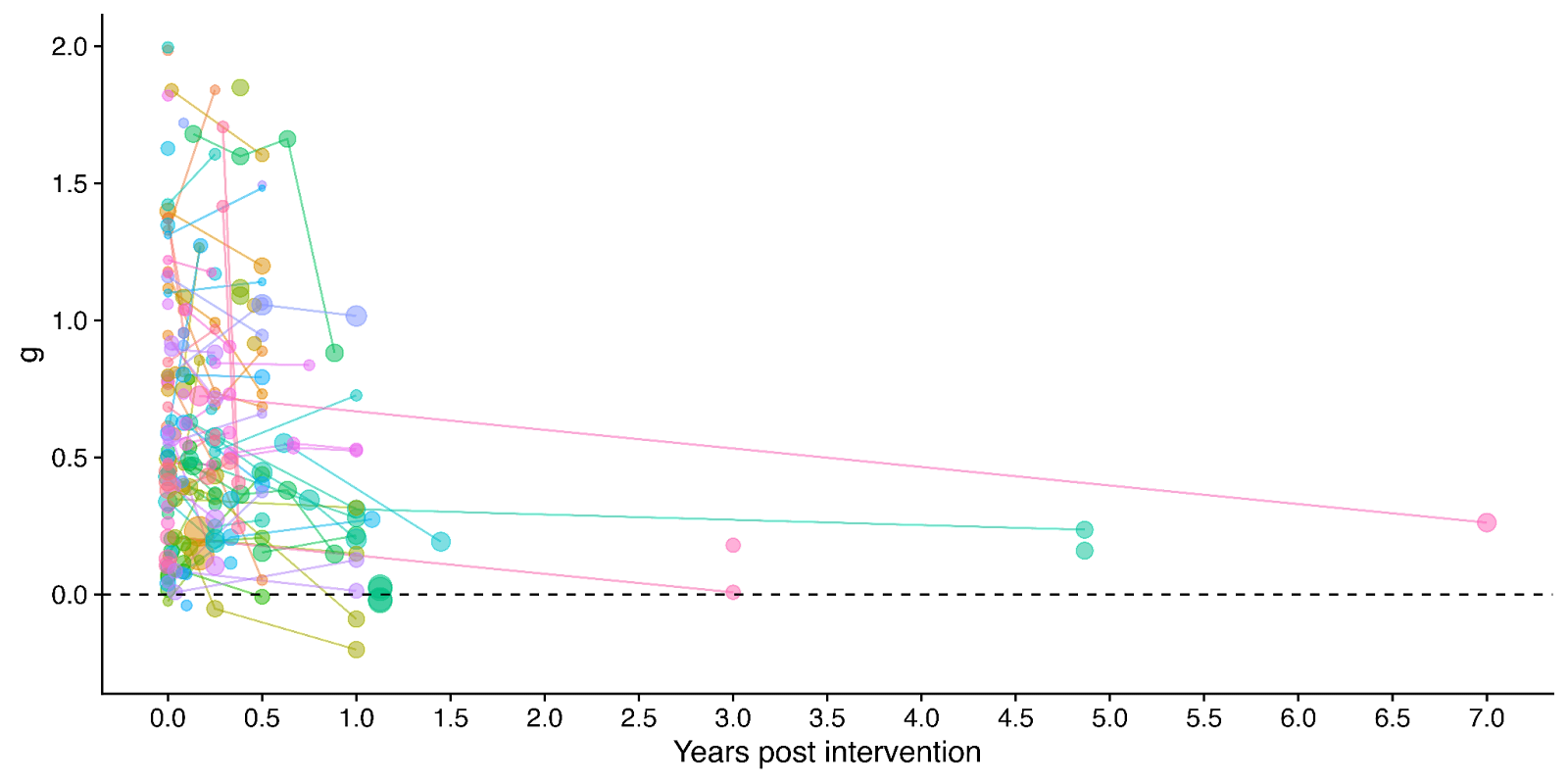

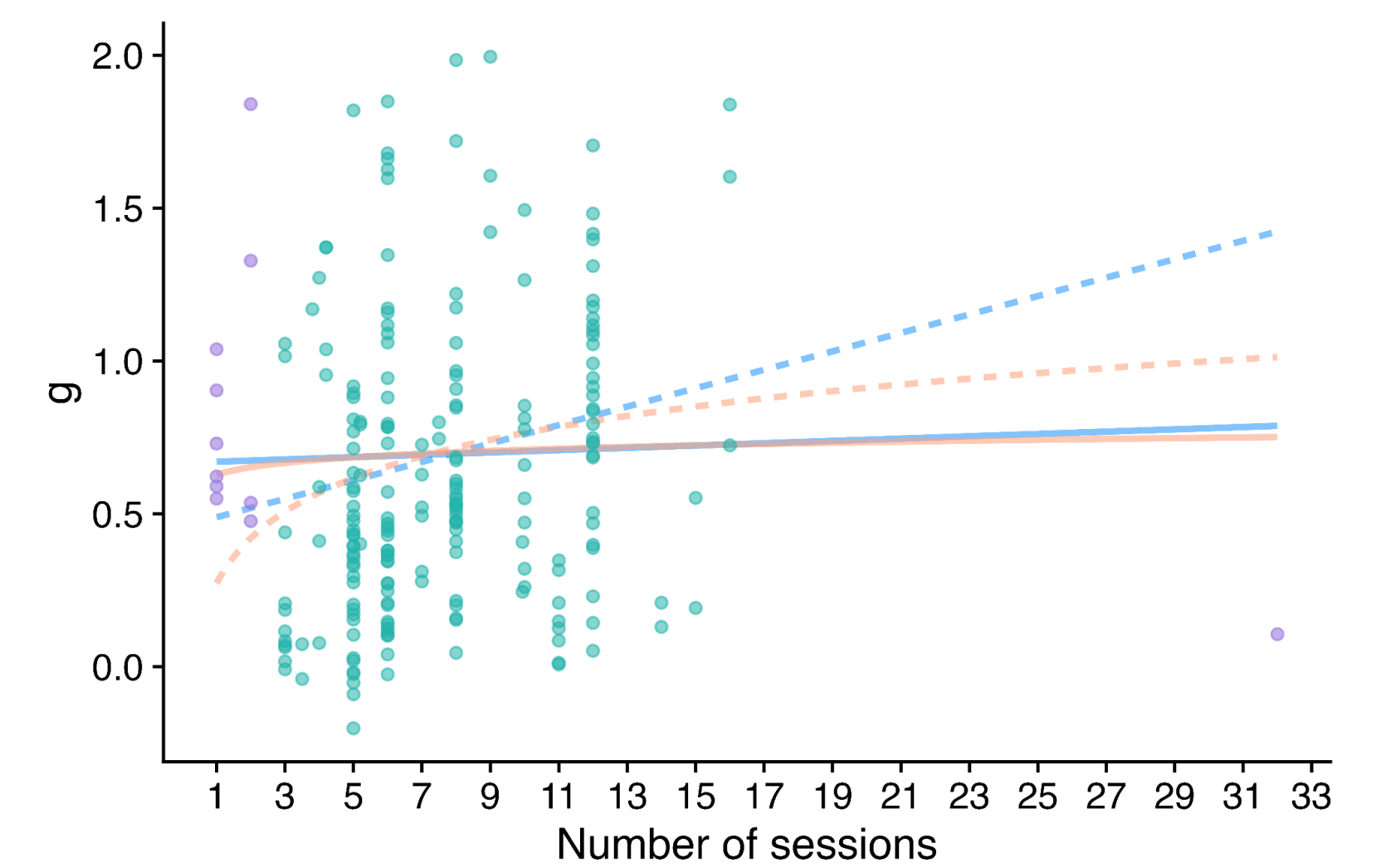

Figure 1: Distribution of the effects for the studies in the meta-analysis, measured in standard deviations change (Hedges’ g) and plotted over time of measurement. The size of the dots represents the sample size of the study. The lines connecting dots indicate follow-up measurements of specific outcomes over time within a study. The average effect is measured 0.37 years after the intervention ends. We discuss the challenges related to integrating unusually long follow-ups in Sections 4.2 and 12 in the report.

2. Update our original estimate of the household spillover effects of psychotherapy.

We collected 5 (previously 2) RCTs to inform our estimate of household spillover effects. We now estimate that the average household member of a psychotherapy recipient benefits 16% as much as the direct recipient (previously 38%). See McGuire et al. (2022b) for our previous report-length treatment of household spillovers.

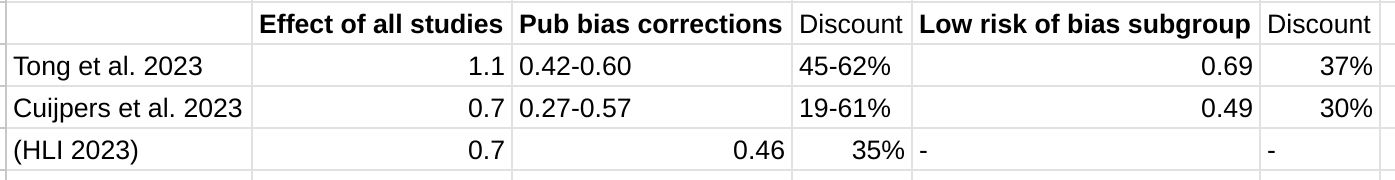

3. Update our original cost-effectiveness analysis of StrongMinds, an NGO that provides group interpersonal psychotherapy in Uganda and Zambia.

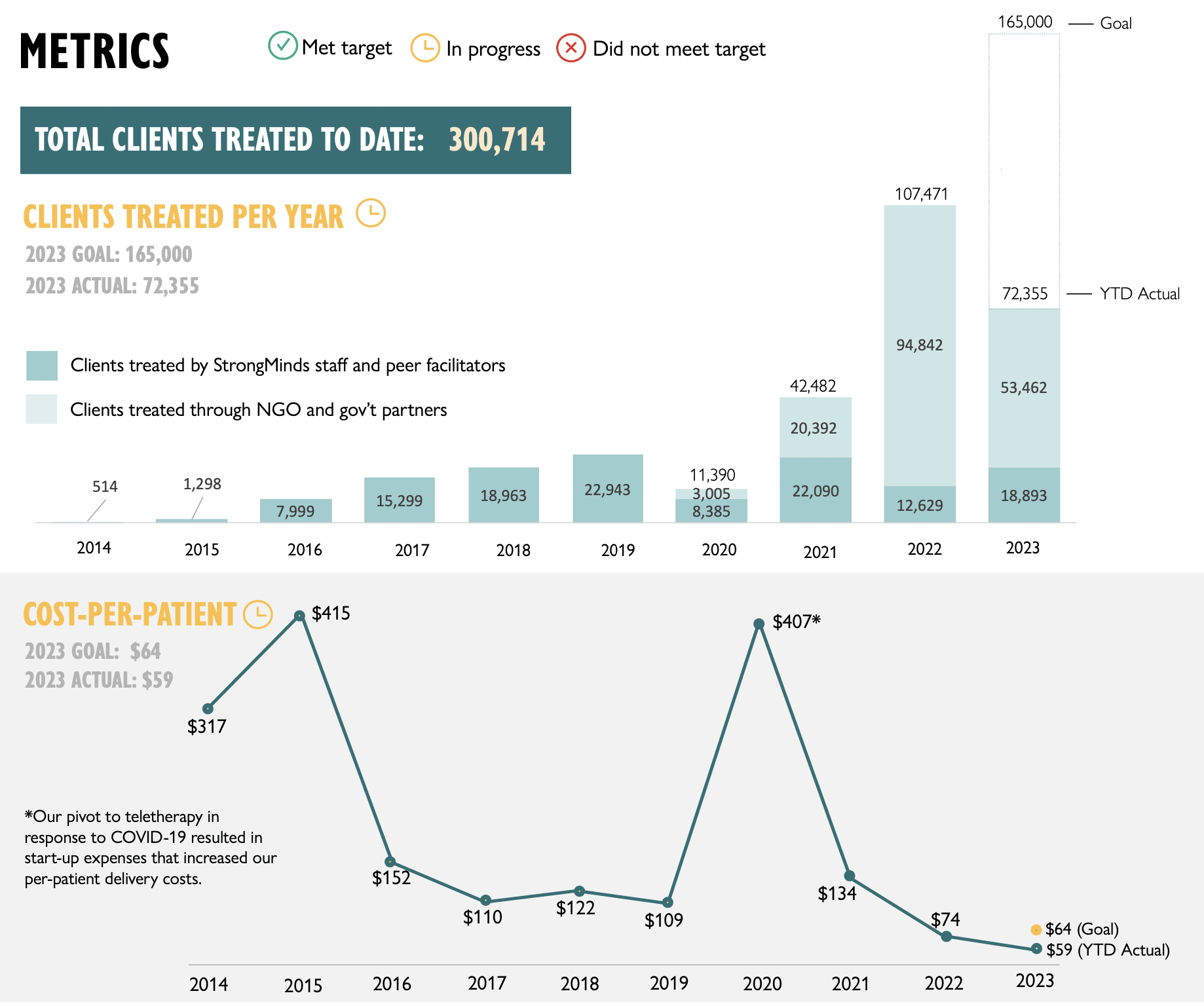

We estimate that a $1,000 donation results in 30 (95% CI: 15, 75) WELLBYs, a 52% reduction from our previous estimate of 62 (see our changelog website page). The cost per person treated for StrongMinds has declined to $63 (previously $170). However, the estimated effect of StrongMinds has also decreased because of smaller household spillovers, StrongMinds-specific characteristics and evidence which suggest smaller-than-average effects, and our inclusion of a discount for publication bias.

The only completed RCT of StrongMinds is the long anticipated study by Baird and co-authors, which has been reported to have found a “small” effect (another RCT is underway). However, this study is not published, so we are unable to include its results and unsure of its exact details and findings. Instead, we use a placeholder value to account for this anticipated small effect as our StrongMinds-specific evidence.[1]

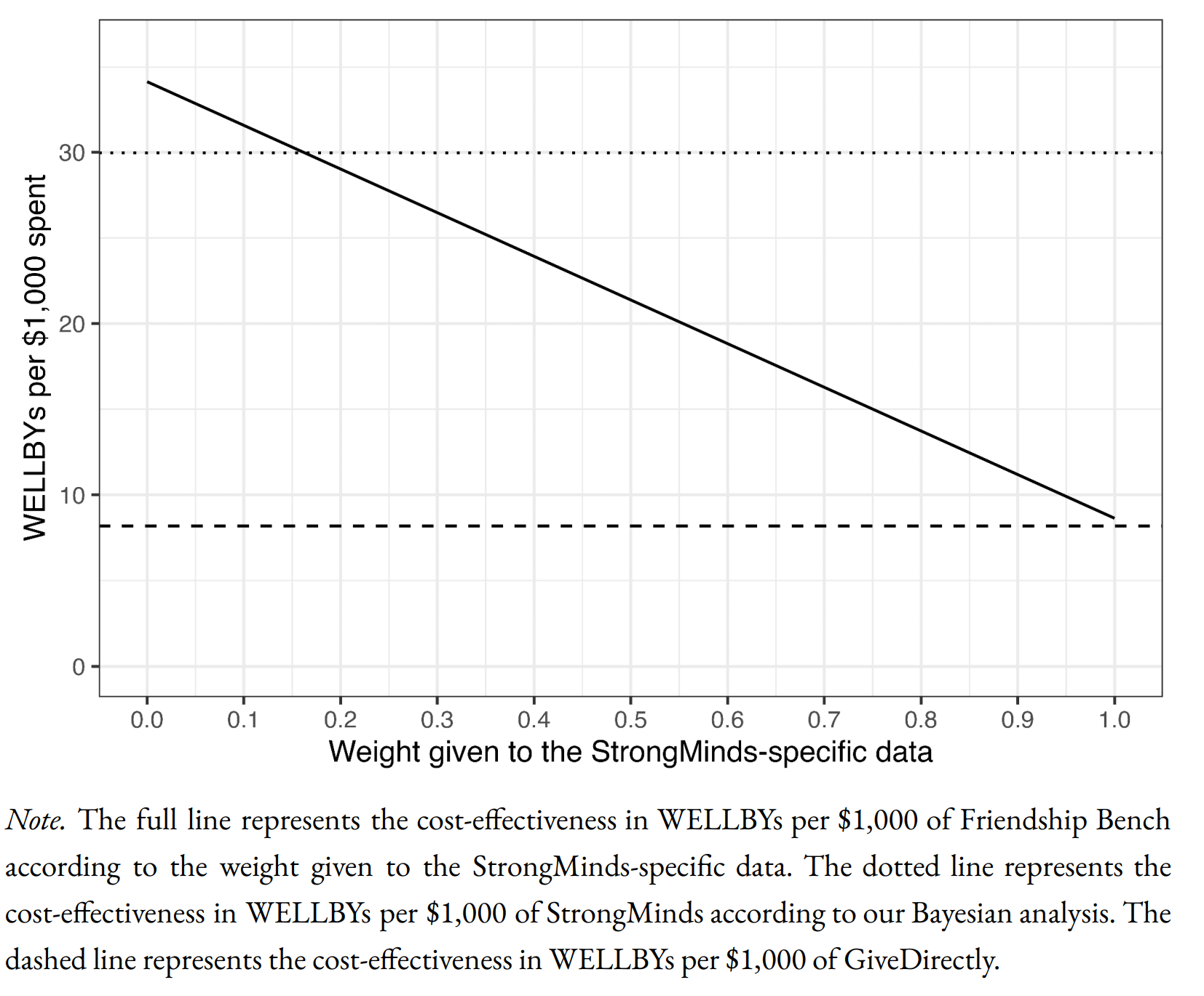

4. Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of Friendship Bench, an NGO that provides individual problem solving therapy in Zimbabwe.

We find a promising but more tentative initial cost-effectiveness estimate for Friendship Bench of 58 (95% CI: 27, 151) WELLBYs per $1,000. Our analysis of Friendship Bench is more tentative because our evaluation of their programme and implementation has been more shallow. It has 3 published RCTs which we use to inform our estimate of the effects of Friendship Bench. We plan to evaluate Friendship Bench in more depth in 2024.

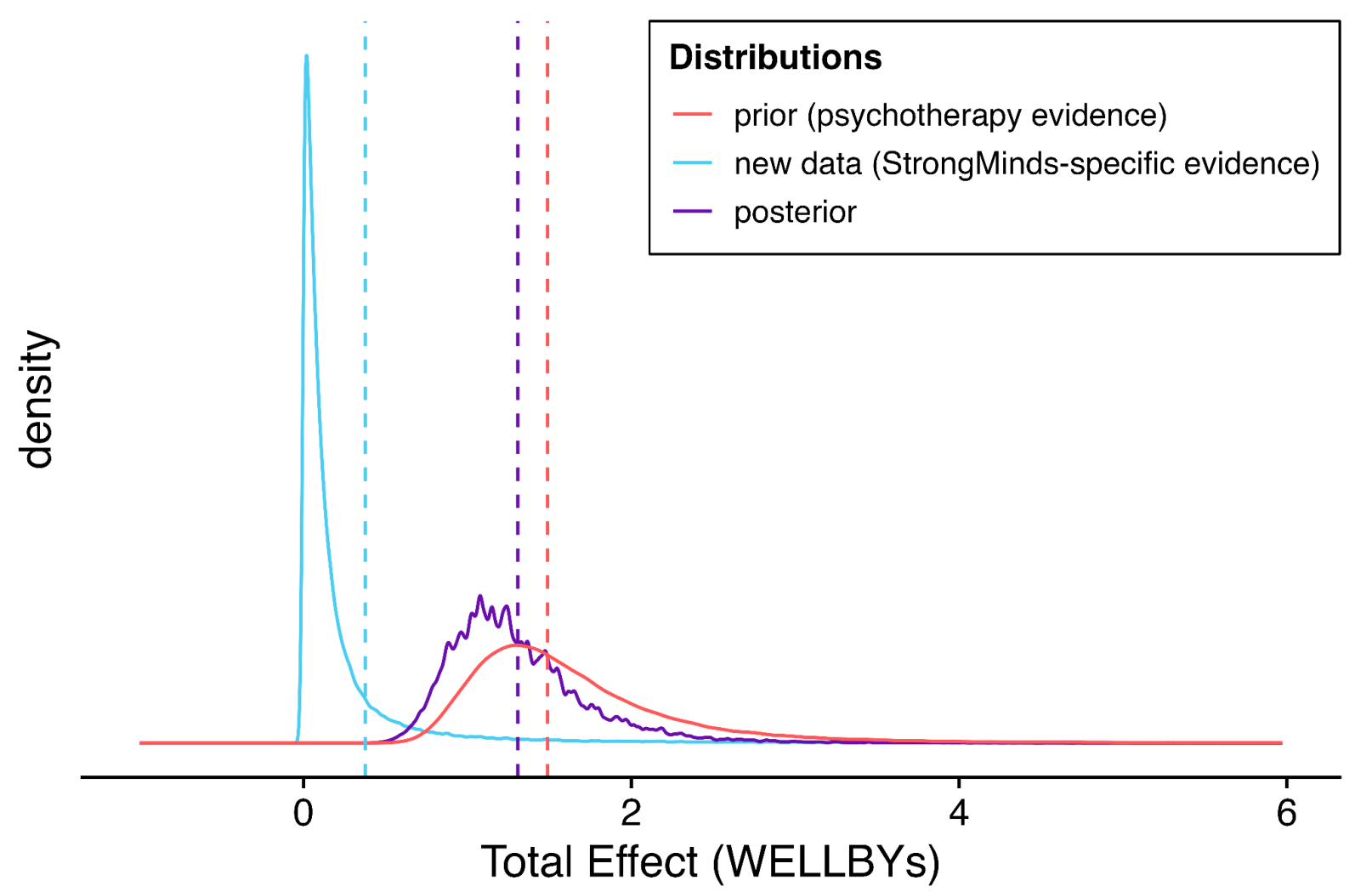

5. Update our charity evaluation methodology.

We improved our methodology for combining our meta-analysis of psychotherapy with charity-specific evidence. Our new method uses Bayesian updating, which provides a formal, statistical basis for combining evidence (previously we used subjective weights). Our rich meta-analytic dataset of psychotherapy trials in LMICs allowed us to predict the effect of charities based on characteristics of their programme such as expertise of the deliverer, whether the therapy was individual or group-based, and the number of sessions attended (previously we used a more rudimentary version of this). We also applied a downwards adjustment for a phenomenon where sample restrictions common to psychotherapy trials inflate effect sizes. We think the overall quality of evidence for psychotherapy is ‘moderate’.

6. Update our comparison to other charities

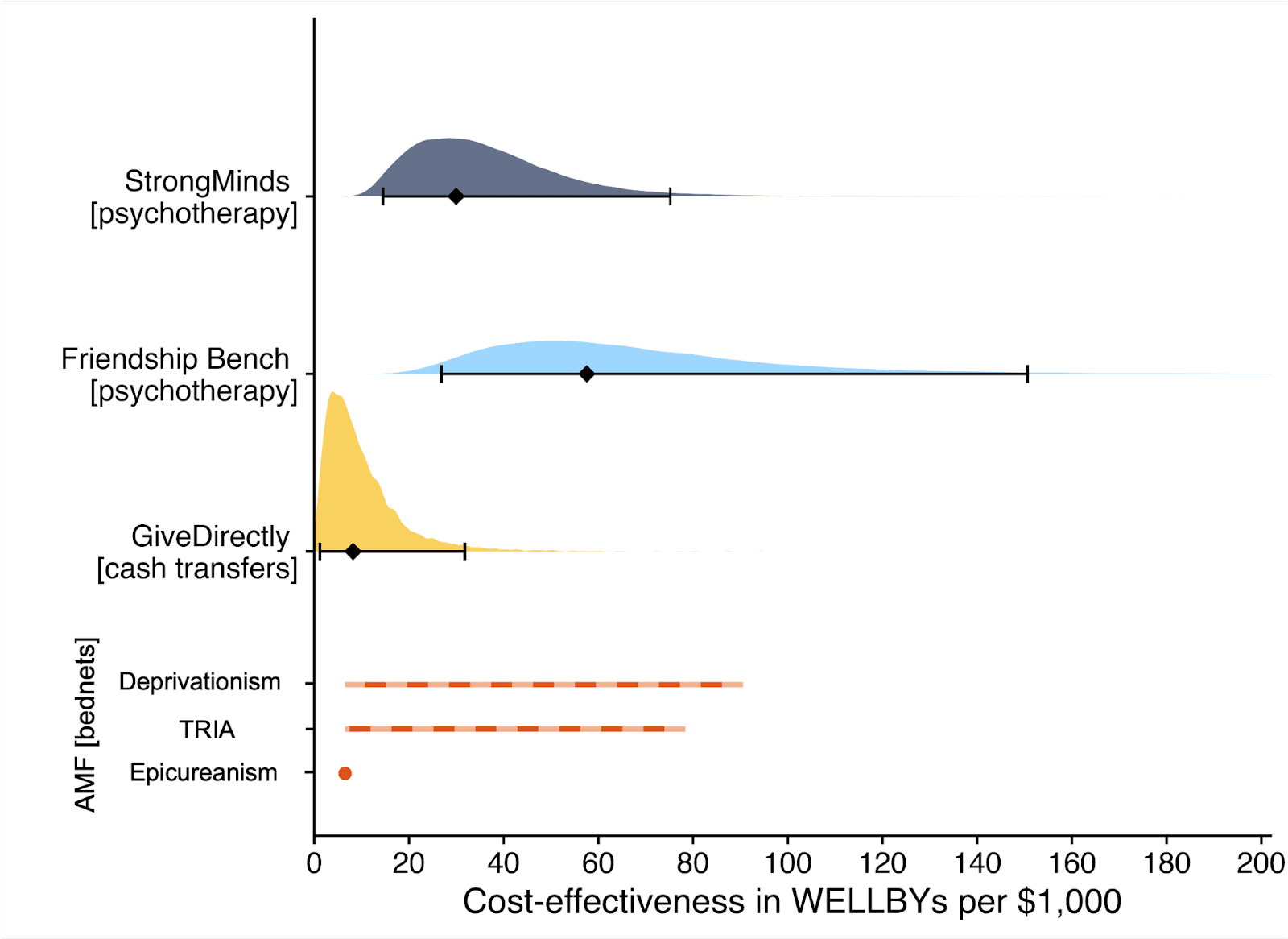

Finally, we compare StrongMinds and Friendship Bench to GiveDirectly cash transfers, which we estimated as 8 (95% CI: 1, 32) WELLBYs per $1,000 (McGuire et al., 2022b). We find here that StrongMinds is 30 (95% CI: 15, 75) WELLBYs per $1,000. Hence, comparing the point estimates, we now estimate that, in WELLBYs, StrongMinds is 3.7x (previously 8x) as cost-effective as GiveDirectly and Friendship Bench is 7.0x as cost-effective as GiveDirectly.

These estimates are largely determined by our estimates of household spillover effects, but the evidence on these effects is much weaker for psychotherapy than cash transfers. It is worth noting that if we only consider the effects on the direct recipient, this increases psychotherapy’s WELLBY effects relative to cash transfers - StrongMinds and Friendship Bench move to 10x and 21x as cost-effective as GiveDirectly, respectively. But it reduces the cost-effectiveness compared to antimalarial bednets. We also present and discuss (Section 12 in the report) how sensitive these results are to the different analytical choices we could have made in our analysis.

Figure 2: Comparison of charity cost-effectiveness. The diamonds represent the central estimate of cost-effectiveness (i.e., the point estimates). The shaded areas are probability density distribution and the solid whiskers represent the 95% confidence intervals for StrongMinds, Friendship Bench, and GiveDirectly. The lines for AMF (the Against Malaria Foundation) are different from the others[2]. Deworming charities are not shown, because we are very uncertain of their cost-effectiveness.

We think this is a moderate-to-in-depth analysis, where we have reviewed most of the available evidence and made many improvements to our methodology. We view the quality of evidence as ‘moderate to high’ for understanding the effect of psychotherapy on its direct recipients in general, ‘low’ for household spillovers, and ‘low to moderate’ for the charity-specific evidence for psychotherapy (StrongMinds and Friendship Bench). Therefore, we see the overall quality of evidence as ‘moderate’.

This is a working report, and results may change over time. We welcome feedback to improve future versions.

Notes

Author note: Joel McGuire, Samuel Dupret, and Ryan Dwyer contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, analysis, data curation, and writing of the project. Michael Plant contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, and writing of the project. Maxwell Klapow contributed to the systematic search and writing.

Reviewer note: We thank, in chronological order, the following reviewers: David Rhys Bernard (for trajectory over time), Ismail Guennouni (for multilevel methodology), Katy Moore (general), Barry Grimes (general), Lily Yu (charity costs), Peter Brietbart (general), Gregory Lewis (general), Ishaan Guptasarma (general), Lingyao Tong (meta-analysis methods and results), Lara Watson (communications).

Charity evaluation note: We thank Jess Brown, Andrew Fraker, and Elly Atuhumuza for providing information about StrongMinds and for their feedback about StrongMinds specific details. We also thank Lena Zamchiya and Ephraim Chiriseri for providing information about Friendship Bench.

Appendix note: This report will be accompanied by an online appendix that we reference for more detail about our methodology and results. The appendix is a working document and will, like this report, be updated over time.

Updates note: This is the first draft of a working paper. New versions will be uploaded over time.

- ^

We use a study that has similar features to the StrongMinds intervention and then discount its results by 95% in the expectation of the Baird et al. study finding a small effect. Note that we do not only rely on StrongMinds-specific evidence in our analysis but combine charity-specific evidence with the results from our general meta-analysis of psychotherapy in a Bayesian manner.

- ^

They represent the upper and lower bound of cost-effectiveness for different philosophical views (not 95% confidence intervals as we haven’t represented any statistical uncertainty for AMF). Think of them as representing moral uncertainty, rather than empirical uncertainty. The upper bound represents the assumptions most generous to extending lives (a low neutral point and age of connectedness) and the lower bound represents those most generous to improving lives (a high neutral point and age of connectedness). The assumptions depend on the neutral point and one’s philosophical view of the badness of death (see Plant et al., 2022, for more detail). These views are summarised as: Deprivationism (the badness of death consists of the wellbeing you would have had if you’d lived longer); Time-relative interest account (TRIA; the badness of death for the individual depends on how ‘connected’ they are to their possible future self. Under this view, lives saved at different ages are assigned different weights); Epicureanism (death is not bad for those who die – this has one value because the neutral point doesn’t affect it).

I have previously let HLI have the last word, but this is too egregious.

Study quality: Publication bias (a property of the literature as a whole) and risk of bias (particular to each individual study which comprise it) are two different things.[1] Accounting for the former does not account for the latter. This is why the Cochrane handbook, the three meta-analyses HLI mentions here, and HLI's own protocol consider distinguish the two.

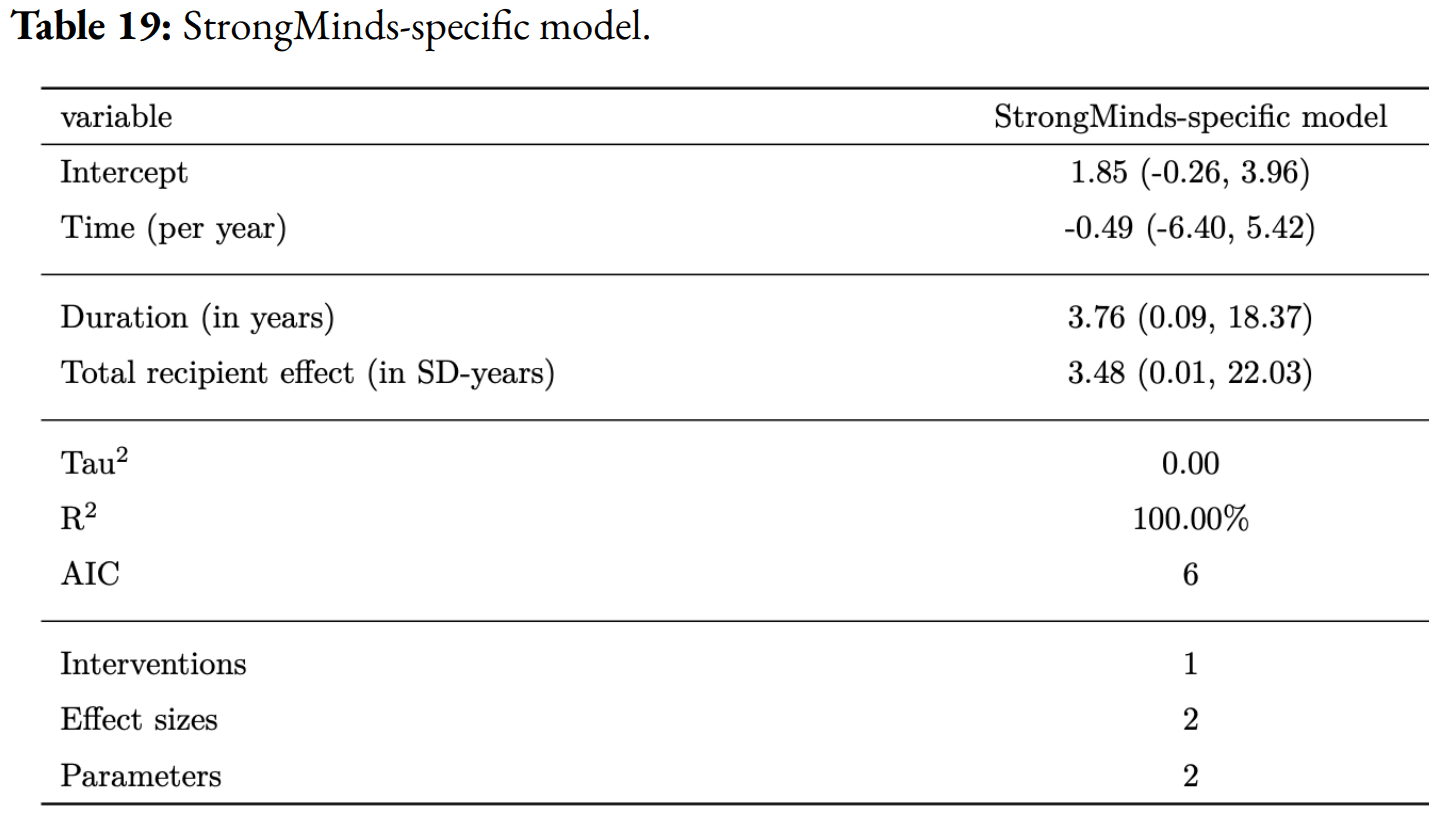

Neither Cuijpers et al. 2023 nor Tong et al. 2023 further adjust their low risk of bias subgroup for publication bias.[2] I tabulate the relevant figures from both studies below:

So HLI indeed gets similar initial results and publication bias adjustments to the two other meta-analyses they find. Yet - although these are not like-for-like - these other two meta-analyses find similarly substantial effect reductions when accounting for study quality as they do when assessing at publication bias of the literature as a whole.

There is ample cause for concern here:[3]

Evidentiary standards: Indeed, the report drew upon a large number of studies. Yet even a synthesis of 72 million (or whatever) studies can be misleading if issues of publication bias, risk of bias in individual studies (and so on) are not appropriately addressed. That an area has 72 (or whatever) studies upon it does not mean it is well-studied, nor would this number (nor any number) be sufficient, by itself, to satisfy any evidentiary standard.

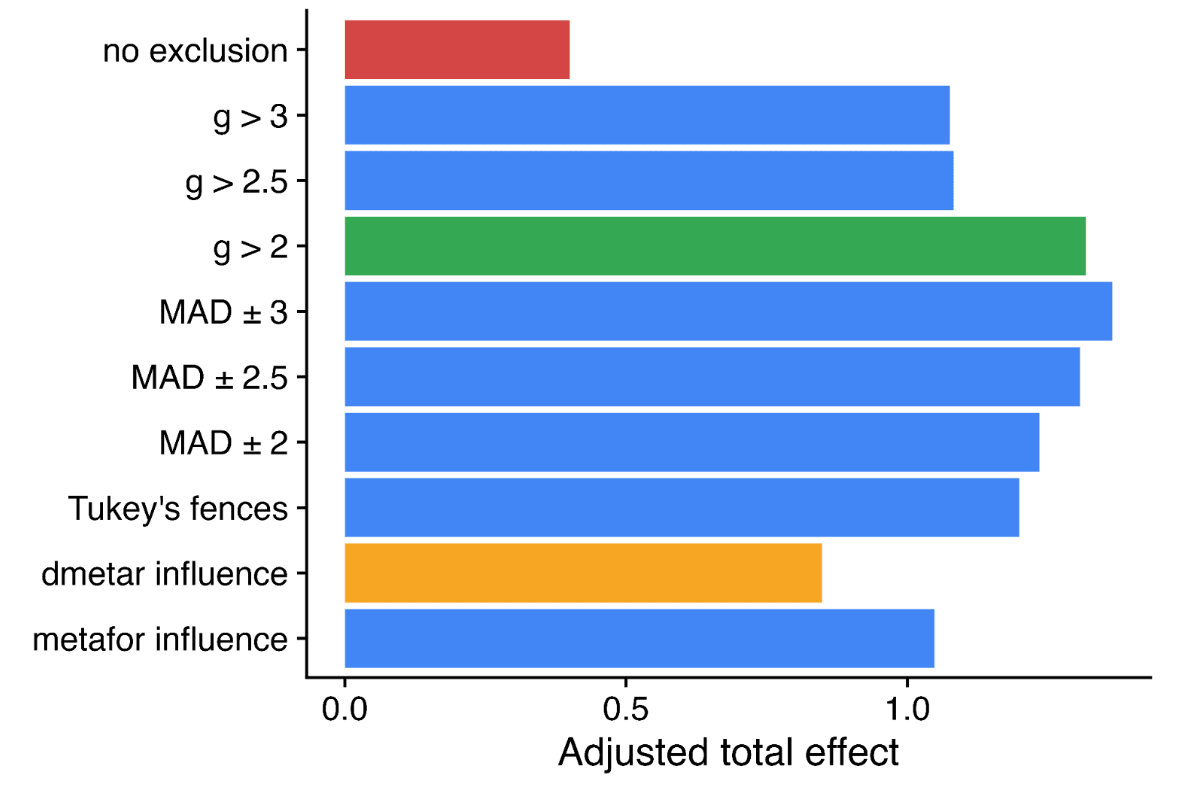

Outlier exclusion: The report's approach to outlier exclusion is dissimilar to both Cuijpers et al. 2020 and Tong et al. 2023, and further is dissimilar with respect to features I highlighted as major causes for concern re. HLI's approach in my original comment.[6] Specifically:

The Cuijpers et al. 2023 meta-analysis previously mentioned also differs in its approach to outlier exclusion from HLI's report in the ways highlighted above. The Cochrane handbook also supports my recommendations on what approach should be taken, which is what the meta-analyses HLI cites approvingly as examples of "sensible practice" actually do, but what HLI's own work does not.

The reports (non) presentation of the stark quantitative sensitivity of its analysis - material to its report bottom line recommendations - to whether outliers are excluded is clearly inappropriate. It is indefensible if, as I have suggested may be the case, the analysis with outliers included was indeed the analysis first contemplated and conducted.[10] It is even worse if it was the publication bias corrections on the full data was what in fact prompted HLI to start making alternative analysis choices which happened to substantially increase the bottom line figures.

Bayesian analysis: Bayesian methods notoriously do not avoid subjective inputs - most importantly here, what information we attend to when constructing an 'informed prior' (or, if one prefers, how to weigh the results with a particular prior stipulated).

In any case, they provide no protection from misunderstanding the calculation being performed, and so misinterpreting the results. The Bayesian method in the report is actually calculating the (adjusted) average effect size of psychotherapy interventions in general, not the expected effect of a given psychotherapy intervention. Although a trial on Strongminds which shows it is relatively ineffectual should not update our view much the efficacy of psychotherapy interventions (/similar to Strongminds) as a whole, it should update us dramatically on the efficacy of Strongminds itself.

Although as a methodological error this is a subtle one (at least, subtle enough for me not to initially pick up on it), the results it gave are nonsense to the naked eye (e.g. SM would still be held as a GiveDirectly-beating intervention even if there were multiple high quality RCTs on Strongminds giving flat or negative results). HLI should have seen this themselves, should have stopped to think after I highlighted these facially invalid outputs of their method in early review, and definitely should not be doubling down on these conclusions even now.

Making recommendations: Although there are other problems, those I have repeated here make the recommendations of the report unsafe. This is why I recommended against publication. Specifically:

(1) and (2) combined should net out to SM < GD; (1) or (2) combined with some of the other sensitivity analyses (e.g. spillovers) will also likely net out to SM < GD. Even if one still believes the bulk of (appropriate) analysis paths still support a recommendation, this sensitivity should be made transparent.

E.g. Even if all studies in the field are conducted impeccably, if journals only accept positive results the literature may still show publication bias. Contrariwise, even if all findings get published, failures in allocation/blinding/etc. could lead to systemic inflation of effect sizes across the literature. In reality - and here - you often have both problems, and they only partially overlap.

Jason correctly interprets Tong et al. 2023: the number of studies included in their publication bias corrections (117 [+36 w/ trim and fill]) equals the number of all studies, not the low risk of bias subgroup (36 - see table 3). I do have access to Cuijpers et al. 2023, which has a very similar results table, with parallel findings (i.e. they do their publication bias corrections on the whole set of studies, not on a low risk of bias subgroup).

Me, previously:

From their discussion (my emphasis):

E.g. from the abstract (my emphasis):

Apparently, all that HLI really meant with "Excluding outliers is thought sensible practice here; two related meta-analyses, Cuijpers et al., 2020c; Tong et al., 2023, used a similar approach" [my emphasis] was merely "[C]onditional on removing outliers, they identify a similar or greater range of effect sizes as outliers as we do." (see).

Yeah, right.

I also had the same impression as Jason that HLI's reply repeatedly strawmans me. The passive aggressive sniping sprinkled throughout and subsequent backpedalling (in fairness, I suspect by people who were not at the keyboard of the corporate account) is less than impressive too. But it's nearly Christmas, so beyond this footnote I'll let all this slide.

Me again (my [re-?]emphasis)

Said footnote:

The sentence in the main text this is a footnote to says:

Me again:

My remark about "Even if you didn't pre-specify, presenting your first cut as the primary analysis helps for nothing up my sleeve reasons" which Dwyer mentions elsewhere was a reference to 'nothing up my sleeve numbers' in cryptography. In the same way picking pi or e initial digits for arbitrary constants reassures the author didn't pick numbers with some ulterior purpose they are not revealing, reporting what one's first analysis showed means readers can compare it to where you ended up after making all the post-hoc judgement calls in the garden of forking paths. "Our first intention analysis would give x, but we ended up convincing ourselves the most appropriate analysis gives a bottom line of 3x" would rightly arouse a lot of scepticism.

I've already mentioned I suspect this is indeed what has happened here: HLI's first cut was including all data, but argued itself into making the choice to exclude, which gave a 3x higher 'bottom line'. Beyond "You didn't say you'd exclude outliers in your protocol" and "basically all of your discussion in the appendix re. outlier exclusion concerns the results of publication bias corrections on the bottom line figures", I kinda feel HLI not denying it is beginning to invite an adverse inference from silence. If I'm right about this, HLI should come clean.