Summary

- I think the following will tend to be the best to maximise the cost-effectiveness of saving a human life:

- Accounting solely for the benefits to the person saved, saving human lives in countries with low, but not too low, real gross domestic product (real GDP) per capita. Saving a human life is cheaper in lower income countries, but self-reported life satisfaction and life expectancy decrease with income. So saving human lives in the lowest income countries may be suboptimal.

- Accounting solely for the benefits from economic growth, saving human lives in countries with high real GDP per capita. Saving a human life is more expensive in higher income countries, but these have greater productivity and life expectancy. So paying more to save human lives there may be worth it.

- In terms of effects on animals, I consider:

- It is unclear whether saving human lives has a positive/negative impact on nearterm welfare accounting for effects on both humans and animals.

- Saving human lives in high income countries is better than in low income countries if the benefits from economic growth dominate. The former increases animal suffering nearterm more, but makes it peak and end earlier, such that there is a greater overall reduction.

- Eating less animals and more whole-food plant-based increases economic growth via decreased mortality.

- My overall view is that:

- If improving nearterm welfare is the best proxy to maximise future welfare, helping animals is arguably better than saving human lives in low income countries.

- If boosting economic growth is the best proxy, saving human lives in high income countries is arguably better than in low income countries.

- I guess improving nearterm welfare is a better proxy than boosting economic growth. Nonetheless, I am mainly in favour of research on whether indirect longterm effects dominate, and, if so, on which are the best proxies for them.

History of my views

My views on saving human lives have evolved roughly as follows:

- I am only able to experience my own experiences, so it is only rational for me to do whatever maximises my own happiness. However, in practice, this means I should also care about others, so saving human lives is good.

- I did not write about the above view, which I think crossed my mind when I was around 13, but it seems close to what I now know as rational egoism.

- All human lives are worth roughly the same, so one had better minimise the cost per life saved, which in practice implies saving human lives in low income countries.

- A vida que podemos salvar (30 March 2021), which translates to “The life you can save”.

- Será que podes fazer a diferença? (27 March 2022), which translates to “Can you make a difference?”.

- Saving human lives in high income countries may well be bad due to the meat-eater problem, as consumption per capita of animals with bad human lives is high there, which reinforces the above conclusion that one had better save human lives in low income countries.

- Are poultry birds really important? Yes… (19 June 2022).

- Saving human lives in low income countries is better than in high income ones, but it is hard to tell whether it is good even there. The effects on animals might dominate those on humans in low income countries too due to the growing consumption per capita of animals with bad lives, and impacts on wild animals.

- Finding bugs in GiveWell's top charities (23 January 2023).

- Scale of the welfare of various animal populations (19 March 2023).

- Prioritising animal welfare over global health and development? (13 May 2023).

The Meat Eater Problem[1] (17 June 2023).

- Badness of eating farmed animals in terms of smoking cigarettes (22 July 2023).

- If improving nearterm welfare is the best proxy to maximise future welfare, helping animals is arguably better than saving human lives in low income countries. If boosting economic growth is the best proxy, saving human lives in high income countries is arguably better than in low income countries.

- This post.

I have had a combination of the above views, but the timeline refers to the most heavily weighted one. Since my views have changed many times, I am not so confident the current one is stable.

Saving human lives

Cost

Assuming some kind of approximate rationality in public policy, I think the cost of saving a human life (c) is roughly proportional to the value of a statistical life (VSL). This is arguably approximately proportional to the real GDP per capita of the country where the life is saved[2] (r). So c = k_c r, where k_c is a constant.

Benefits

I believe the benefits of saving a human life to the person saved (u_0) are roughly proportional to the self-reported life satisfaction times the life expectancy at birth. Both of these factors are arguably approximately proportional to the logarithm of the ratio between the real GDP per capita of the country where the life is saved and that respecting a neutral life (r_0). So u_0 = k_u_0 ln(r/r_0)^2, where k_u_0 is a constant.

The above does not capture all the benefits of saving human lives due to indirect longterm effects. Based on an outside view perspective, one can say these (u_1) are roughly proportional to the advancement in time of the trajectory of the global real GDP[3], as economic growth is one of the best markers of progress[4], although arguably still far from ideal. Such advancement decreases astronomical waste, may decrease extinction risk, and is arguably approximately proportional to the real GDP per capita of the country where the life is saved times the life expectancy at birth there[5], which I suggested above is proportional to ln(r/r_0). So u_1 = k_u_1 r ln(r/r_0), where k_u_1 is a constant. This translates into the uncomfortable conclusion of human lives in higher income countries being instrumentally more valuable[6]. I am not confident this is right/wrong, but here are some thoughts:

- One can argue naively increasing economic growth is worse than acting as if all human lives have similar total (intrinsic plus instrumental) value, since this promotes cooperation and peace, which are great heuristics for beneficial indirect longterm effects. On the other hand, boosting economic growth is often a good way to bring about cooperation and peace. For instance, open borders could double GDP (or not).

- While valuing human lives differently may seem counterintuitive in effective altruism circles (or not), it is the view:

- Endorsed by the vast majority of governments, at least implicitly. Otherwise, there would not be huge differences in the VSL across countries.

Followed to a significant extent in personal human lives. Someone strongly endorsing impartiality has to appeal to instrumental reasons to justify caring much more about 1 unit of welfare in one’s friends and family than in serial killers[7].

- Both maximising economic growth and nearterm welfare impartially have counterintuitive implications. To maximise:

- Economic growth, it would make sense for an altruistic person to accept a 50 % chance of more than doubling productivity plus a 50 % chance of dying.

- Nearterm welfare, it would also make sense to accept the deal just above, because the donations one can make to save human lives are arguably proportional to one’s productivity.

In addition, there is a case for economic growth being a good way of increasing nearterm human welfare.

Cost-effectiveness

Based on the above, the cost-effectiveness of saving a human life is:

- Accounting solely for the benefits to the person saved, u_0/c = (k_u_0/k_c) ln(r/r_0)^2/r.

Accounting solely for the benefits from economic growth, u_1/c = (k_u_1/k_c) ln(r/r_0)[8].

As a result, the following will tend to be the best to maximise cost-effectiveness:

Accounting solely for the benefits to the person saved, saving human lives in countries whose real GDP per capita is 7.39 (= e^2) times that respecting a neutral life[9].

I think r_0 is around 314 2017-$ (= 0.86*365.25), given a calorie sufficient diet in low income countries costed 0.86 2017-$/person/d in 2017. If so, my approach suggests saving a human life would be optimal in a country with a real GDP per capita of 2.32 k 2017-$ (= 7.39*314). For context, this was Ethiopia’s value in 2021.

Minimising the cost to save a human life may not be the best heuristic. If it is too low, the decrease in benefits may outweigh the lower cost such that cost-effectiveness is lower. Burundi had the lowest real GDP per capita in 2021 of 714 2017-$, which is 30.8 % (= 714/(2.32*10^3)) of my estimate for the optimum.

Accounting solely for the benefits from economic growth, saving human lives in countries with the highest real GDP per capita[10]. This makes intuitive sense under the view that progress is driven by research and development (R&D).

High income countries had 4.12 k R&D researchers per million people in 2015, 13.3 (= 4.12/0.309) times as many as lower-middle income countries.

There was no data for low income countries, but Ethiopia, which is aiming to become a lower-middle income by 2025, had 91 R&D researchers per million people in 2017, 2.09 % (= 0.091/4.36) as many as high income countries.

- Accounting solely for the benefits to the person saved, additional wellbeing years (WELLBYs) per dollar spent.

Accounting solely for the benefits from economic growth, additional global real GDP per dollar spent[11].

Note these are just heuristics I am discussing for illustrative purposes. Rather than picking a country based on real GDP per capita, one had better maximise the proxies more strictly connected to the target outcomes:

It makes sense to account for both benefits, but I am uncertain about which one, if any, dominates (relatedly). There is also room for debate about what are the best proxies for each of the above benefits, although they often correlate well with each other. Respecting:

- The benefits to the person saved, less disease improves wellbeing.

- The benefits from economic growth:

Across countries, I estimated a correlation of 0.767 between the logarithm of the real GDP per capita and the Future Expected Value Index (FEVI), which I defined as the mean of 14 socioeconomic indices[12].

- Global real GDP has increased with global real GDP per capita.

In contrast, it is not immediately clear how the metrics I have discussed capture effects on animals.

Effects on animals

Impacting nearterm animal welfare

I have argued interventions focussed on helping humans should account for the effects on animals, as they may well be beneficial/harmful. In the context of human diet, there is the meat-eater problem:

The meat-eater problem (sometimes called the poor meat-eater problem) is the concern that some interventions aimed at helping humans might increase animal product consumption and as a result increase farmed animal suffering, e.g. by increasing real income or human population.

I estimated the cost-effectiveness of GiveWell’s top charities is only reduced by 8.72 % due to the negative impact on farmed animals, such that they remain beneficial. On the other hand, I have used the current consumption of poultry per capita, but this, as well as that of other farmed animals, will tend to increase with economic growth. I estimated the badness of the experiences of all farmed animals alive is 4.64 times the goodness of the experiences of all humans alive[13], which suggests saving a random human life results in a nearterm increase in suffering (relatedly). Moreover, the beneficial/harmful effect on wild animals may well be much larger.

For the above reasons, I consider it is unclear whether saving human lives has a positive/negative impact on nearterm welfare. My estimates are not resilient, but I see this as an additional source of sign uncertainty[14]. However, saving human lives may also shape longterm animal welfare.

Shaping longterm animal welfare

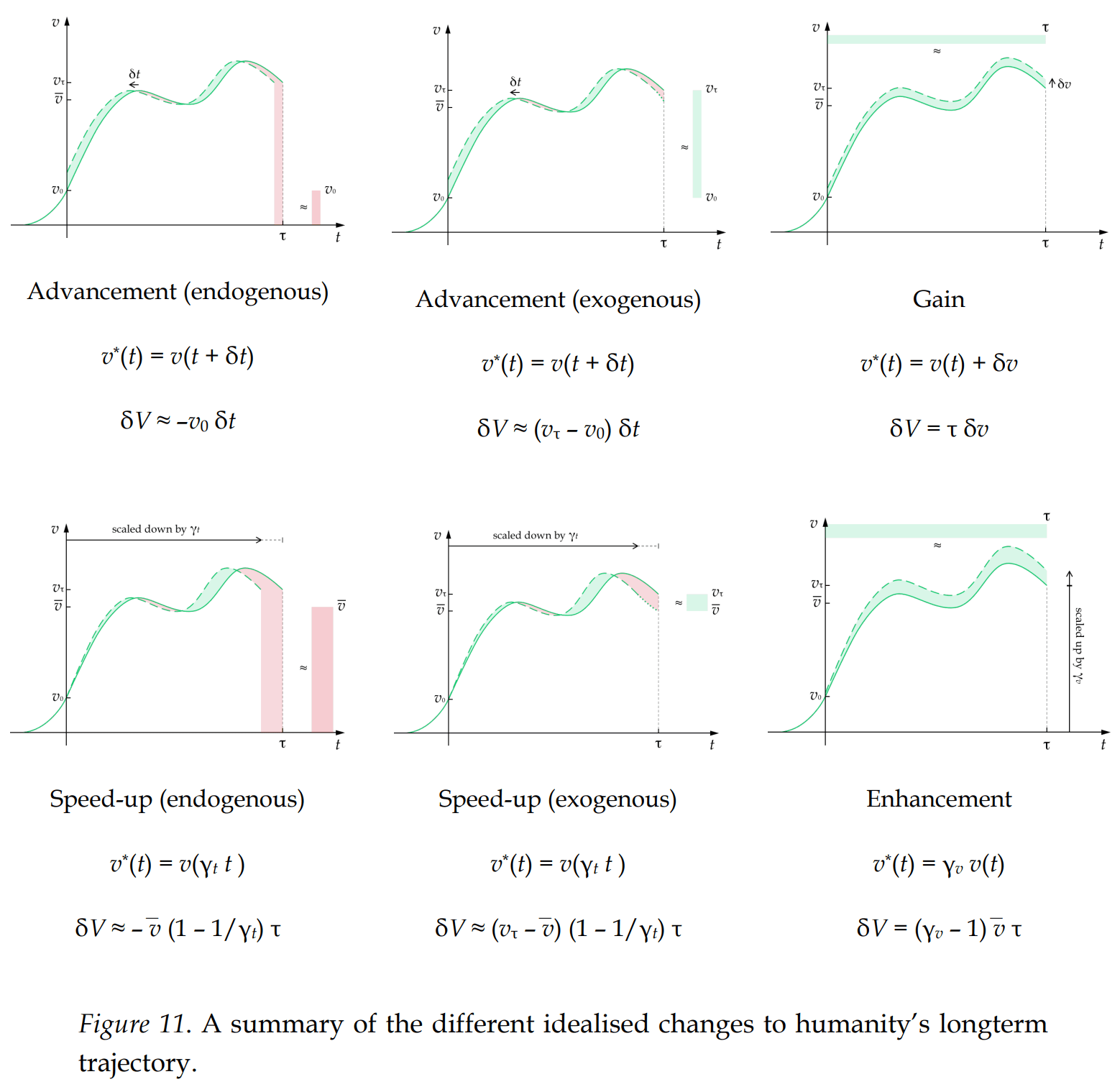

Toby Ord describes 6 ways of changing humanity’s future value:

I think the above framework can be used to assess the indirect longterm effects of saving human lives on animal welfare. To this end, one can imagine:

- The vertical axis respects animal suffering (instead of humanity’s value).

- respects the time until the end of animal suffering (instead of the time until the end of humanity’s value).

The time just mentioned is endogenous/related to humanity’s activities, and I believe greater economic growth can a priori be represented as an advancement or speed-up. So it increases animal suffering nearterm, but makes it peak and end earlier, such that there is an overall reduction of:

- For an advancement, “current annual animal suffering”*“advancement in years” (top left graph).

- For a speed-up, “mean annual animal suffering until it ends”*(1 - 1/“speed-up factor”)*“time until animal suffering ends in years” (bottom left graph).

Consequently, it appears that saving human lives will tend to decrease animal suffering if it increases economic growth. Likewise for other interventions. Furthermore, the above expressions suggest the reduction in animal suffering is larger for greater “current annual animal suffering”. Since higher real GDP per capita is associated with greater consumption of animals, and this is linked to greater animal suffering, saving human lives in higher income countries will tend to decrease animal suffering more.

Nevertheless, greater economic growth does not necessarily lead to less animal suffering (nor differential progress). I guess it does in expectation, but there is lots of uncertainty, and work explicitly focussed on improving animal welfare is still very much worth it. Michael St. Jules commented, rightly in my view, that[15]:

It’s worth pointing out that it’s largely due to the work of effective animal advocacy [EAA] that animal suffering is being reduced. This hasn’t happened for free or by default; we’re paying for it.

Some EAAs are interested in slowing the growth of factory farming or worst practices (like cages) and possibly even preventing it where it’s not yet very established and animal product consumption remains low, including in parts of Africa (see work supported by the Open Wing Alliance, the EA Animal Welfare Fund or Animal Advocacy Africa, like Utunzi Animal Welfare Organization). Economic growth could make that work harder, because economic growth drives intensification and animal product consumption (see also Gilbert 2015).

I agree that given similar rates of factory farmed animal products per capita, it’s easier to reduce factory farming if people are richer, though, because willingness to pay for animal welfare is probably higher. So maybe it will make our work cheaper then, or maybe it will even happen without us. But it could make our work harder now, and we miss the chance to prevent some intensification early on [relatedly].

Does saving human lives increase economic growth?

In general, I suppose it is fair to say saving human lives increases economic growth, since labour is one of inputs (relatedly), unless we are talking about people who have already retired[16]. So saving human lives will tend to decrease animal suffering if this follows from boosting economic growth.

Here is the answer from ChatGPT 4 to the question just above (with minor changes to the text format):

The question of whether saving human lives increases economic growth is multifaceted and involves understanding the complex interplay between health and economic development. There are several key aspects to consider:

- Workforce Productivity. Improved health typically leads to increased productivity. Healthy individuals can work more effectively, take fewer sick days, and contribute more actively to the economy. This increase in productivity can lead to higher economic output.

- Demographic Changes. Saving human lives, especially in younger populations, can contribute to a demographic dividend. This term refers to the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population's age structure, mainly when the working-age population grows larger relative to the number of dependents.

- Human Capital Development. Health is a component of human capital. When people live longer and healthier human lives, they can invest more in education and skill development, enhancing their employability and potential for innovation, which is vital for economic growth.

- Healthcare Costs. On the flip side, increasing life expectancy can raise healthcare costs, especially in ageing populations. This scenario can strain public health systems and divert resources from other economic activities.

- Dependency Ratio. If life-saving measures primarily extend the human lives of the elderly, this could increase the dependency ratio (the ratio of non-working-age to working-age people). A higher dependency ratio can place a financial burden on the working population, potentially slowing economic growth.

- Empirical Evidence. Studies have shown a positive correlation between health improvements and economic growth. For example, research by the World Health Organization and others suggests that investments in health lead to economic growth by improving productivity, reducing healthcare costs, and enhancing the quality of human capital.

- Long-Term Perspective. The impact of saving human lives on economic growth may vary in the short term versus the long term. In the short term, rapid population growth due to decreased mortality can strain resources, but in the long term, it can lead to a more skilled and productive workforce.

In summary, while saving human lives can certainly contribute to economic growth, the exact nature of this relationship depends on various factors, including the age distribution of those whose human lives are saved, the overall health of the population, and the capacity of the economy to absorb and utilise a growing workforce.

See also:

📈 Economic impact of healthcare to explore how health improvements can drive economic growth.

🧑🏫 Human capital theory for understanding the role of health in human capital development.

You may also enjoy:

🌏 Global Health Initiatives to see how worldwide health programs affect various economies.

📊 Demographic dividend for insights into how population dynamics influence economic growth.

Eating less animals and more whole-food plant-based increases economic growth

Economic growth may increase animal suffering nearterm via resulting in greater consumption of animals. Nonetheless, I believe there is a good case for eating less animals and more whole-food plant-based to increase economic growth:

According to the EAT-Lancet Commision, the global adoption of a predominantly plant-based healthy diet, with just 13.6 %[17] (= (153 + 15 + 15 + 62 + 19 + 40 + 36)/2500) of calories coming from animals, would decrease premature deaths of adults by 21.7 %[18] (= (0.19 + 0.224 + 0.236)/3). Less premature mortality implies more time to contribute to economic growth.

- From Springmann 2015, “as a percentage of expected world gross domestic product (GDP) in 2050, these [annual] savings amount to 2.3% (1.5–3.1%) for HGD diets [healthy global diets], 3.0% (2.0–4.0%) for VGT [vegetarian] diets, and 3.3% (2.2–4.4%) for VGN [vegan] diets”.

- “The second scenario [healthy global diets (HGD)] assumes the implementation of global dietary guidelines on healthy eating (16, 28) and that people consume just enough calories to maintain a healthy body weight (29)”. As with the EAT-Lancet diet, adopting healthy global diets would imply a major reduction in the consumption of animals. “The HGD diet included (per day) a minimum of five portions of fruits and vegetables (16), fewer than 50 g of sugar (16), a maximum of 43 g of red meat (28), and an energy content of 2,200–2,300 kcal, depending on the age and sex composition of the population (29)”.

- “The last two scenarios also assume a healthy energy intake but based on observed vegetarian diets (30, 31), either including eggs and dairy [lacto-ovo vegetarian (VGT)] or completely plant-based [vegan (VGN)]”. I think this means the vegetarian and vegan diets are not optimised for health. They just correspond to the diets vegetarians and vegans actually follow in the real world.

My overall view

If improving nearterm welfare is the best proxy to increase future welfare, helping animals is arguably better than saving human lives in low income countries. I estimate corporate campaigns for chicken welfare increase nearterm welfare 1.37 k times as cost-effectively as GiveWell’s top charities, and I am not confident that saving human lives is good/bad accounting for effects on animals[19].

If boosting economic growth is the best proxy, saving human lives in high income countries is arguably better than in low income countries. However, in this case, I would not see changing population size as a top area, and may prioritise AI safety interventions.

I suppose one has to hold the total view in order for improving nearterm welfare to be a better proxy than boosting economic growth. I believe the first agricultural revolution was for the better, but it may well have resulted in a lower quality of life nearterm, whereas it arguably increased total welfare via facilitating population growth.

I guess improving nearterm welfare is a better proxy than boosting economic growth. Nonetheless, I mostly agree with Richard Chappell that effective altruism’s worldviews need rethinking. I am mainly in favour of research on whether indirect longterm effects dominate, and, if so, on which are the best proxies for them. I have the sense the effective altruism community prematurely converged on minimising (human) disease burden, potentially even in the context of global catastrophes, without giving sufficient credit to alternatives. For example, increasing global real GDP, or (my preference of) improving the welfare of humans plus animals. On the one hand, I strongly endorse expected total hedonistic utilitarianism, and would agree that minimising disease burden as typically defined is one of the best available proxies for it. On the other, further research on what to maximise seems useful to make the maximisation less perilous.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Anonymous Person and Ramiro Peres for feedback on the draft. Thanks to Michael St. Jules for feedback on the 3 1st subsections of Effects on animals.

- ^

Linkpost with some commentary of mine.

- ^

In agreement with Viscusi 2020. “For international differences [respecting VSL], I adopt an income elasticity figure of 1.0”.

- ^

See advancement of a value trajectory with an exogenous end in Figure 11.

- ^

See also Tyler Cowen’s book Stubborn Attachments, which was discussed on The 80,000 Hours Podcast. Applied Divinity Studies has a related piece on the moral foundations of progress.

- ^

Ideally, one would account for emigration and catch-up growth.

- ^

Relatedly, one of the sections of Tyler Cowen’s book Stubborn Attachments is “Should Money Be Redistributed to the Rich?”.

- ^

This can be read as the special obligations objection to utilitarianism, which I do not think goes through (see responses in the link).

- ^

For reference, if I had assumed the benefits from economic growth were proportional to the real GDP per capita of the country where the life is saved, but not to the life expectancy at birth there, u_1/c = k_u_1/k_c. Consequently, in that case, the cost-effectiveness of saving a human life accounting solely for the benefits from economic growth would not depend on the real GDP per capita of the country where the life is saved.

- ^

The derivative of u_0/c with respect to r is (k_u_0/k_c) ln(r/r_0) (2 - ln(r/r_0))/r^2, which is null for r = e^2 r_0. This is a maximum because u_0/c goes to 0 as r tends to r_0 or infinity.

- ^

u_1/c increases with r.

- ^

- ^

- ^

Based on the conditions of broilers in a reformed scenario.

- ^

Uncertainty about whether saving human lives increases or decreases nearterm welfare.

- ^

I just added some of the links.

- ^

Even then, people who are no longer formally employed can still work (e.g. caring for grandchildren).

- ^

Calculated based on values in Table 1.

- ^

Mean of the 3 estimates in Table 3.

- ^

Although there is some nuance.

Executive summary: Saving human lives in high income countries may be better than in low income countries from the perspective of boosting economic growth, while helping animals may be better than saving human lives in low income countries from the perspective of improving near-term welfare.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

"If boosting economic growth is the best proxy" to future welfare...

I feel like this is a real crux here, because to me it seems counterintuitive to the point of absurd when applied to high income countries, but I'm always trying to keep an open mind. I can understand how economic growth could be a proxy in a low income country as welfare is likely to increase as a poor country gets richer.

It doesn't seem to me likely that high economic growth in an already rich country would increase welfare very much at all. Can you point me to a resource which steelman's this idea?

Thanks for the comment and keeping an open mind, Nick!

Just for reference, I share your intuition that one should not be focussing on economic growth:

However:

Intuitively, I would say doubling the income of everyone in high income countries would lead to greater nearterm human welfare (although it may decrease overall nearterm welfare due to increasing consumption of factory-farmed animals). However, I think the paper Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved is one of the best resources on this question. Here is the abstract:

Across countries, self-reported life satisfaction is correlated with real GDP per capita even for high income countries, which have a gross national income per capita of at least 13.8 k 2022-$:

Zooming out, you may want to have a look at some of the links here:

In one of the footnotes, I mention Tyler Cowen’s book Stubborn Attachments, which was discussed on The 80,000 Hours Podcast.

Thanks for the interesting post - definitely gives one some things to think about!

Here’s another point to consider: depending on the costs, one of the most effective interventions may be to raise the self-esteem levels of people in high income countries. Note: I’m operating under a model in which self-esteem is determined primarily by personal responsibility level, first for one’s emotions and then one’s actions (see “The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem” by N. Branden). Raising people’s self-esteem levels should raise their self-reported life satisfactions, and also likely have secondary effects on those they interact with. In addition, people who have higher self-esteem due to being more responsible are more likely to practice responsibility in terms of human and animal suffering (as by donating to causes and/or going vegetarian/vegan, with people from high income countries having more potential impact here). Of course, raising self-esteem levels in low income countries could also be quite beneficial - for instance, higher self-esteem people may be more of a driving force for raising health standards in their countries.

The concept of self-esteem has a somewhat checkered history in psychology. Here, an influential review paper finds that self-esteem leads people to speak up more in groups and to feel happier. But it fails to have consistent benefits in other areas of life such as educational/occupational performance or violence. And it may have detrimental effects, such as risky behavior in teens.

Thanks for the comment and the link to the review paper!

I think most people, including researchers, don't have a good handle on what self-esteem is, or at least what truly raises or lowers it - I would expect the effect of praise to be weak, but the effect of promoting responsibility for one's emotions and actions to be strong. The closest to my views on self-esteem that I've found so far are those in N. Branden's "Six Pillars of Self-Esteem" - the six pillars are living consciously, self-acceptance, self-responsibility, self-assertiveness, living purposefully, and personal integrity.

Unfortunately, because many researchers don't follow this conception of self-esteem, I tend not to trust much research on the real-world effects of self-esteem. Honestly, though, I haven't done a hard search for any research that uses something close to my conception of self-esteem, and your comment has basically pointed out that I should get on that, so thank you!

Thanks for commenting, and welcome to the EA Forum, Sean! I wonder whether there are cost-effectiveness analyses of interventions aiming to raise self-esteem.

Thanks. I don't know the answer to that, although a quick search didn't yield anything too promising. I don't believe the concept of self-esteem as being primarily about personal responsibility has really caught on, so perhaps it would be better to look for studies on interventions to raise personal responsibility.

Thank you for this post, Vasco.

I'm really glad to see a post challenging what seems to be the status quo opinion of saving lives in cheapest countries is the best / 'most effective' thing to do. (Perhaps there are more posts challenging this - I'm still new to the forum and haven't gone through the archives, but from what I've seen more generally, the saving lives most cheaply view seems to be fairly ubiquitous and I worry it's an overly simplistic way to look at things)

I tend to agree that focusing on cost to save a life is not necessarily the best proxy for effectiveness, and that considering WELLBY type metrics seems a very sensible thing to take into account.

I also think there's a bit of an under-consideration in common discourse of indirect effects. If you save a life in a rich country, does that sometimes have the potential to do more good overall because they might, post-intervention be in a better position to help others with donations/volunteering/high tax contribution? And if we only addressed what's espoused to be "the most cost-effective" - only the malaria net charities etc. and we ignore dealing with more expensive issues, we could make the issues we neglect exponentially worse and do more harm than good. It's not necessarily the case that the more expensive issues just say constant if we don't fund interventions for them. The world is far more complex than that. Many problems have a tipping point where things get much worse beyond a set point, and if we just say 'no funding for causes not on the effective charities lists' there's a strategic cost/implication to that. For example, child exploitation by criminal gangs - not something you find on the cause prioritisation lists, but if nothing is done to address issues like that, guess what - organised crime thrives without challenge and it becomes a much, much more complex, expensive problem to fix. (There are probably better examples, but I did find this https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-68615776 from the UK news today really interesting and it seems like an example where there is a problem getting worse and without attention it will become effectively an epidemic. Yet, the general EA wisdom would say funding charities that try to help children escape exploitation by criminal gangs is not cost-effective so don't put it on your list - don't we need a more nuanced view?)

Cause prioritisation is really important, considering effectiveness and cost-effectiveneness is really important, but it feels like the model needs to evolve to something a bit less simplistic than how many lives can you save with £X. To be clear, I do genuinely think charities like Against Malaria Foundation and GiveDirectly are fantastic and should receive a high level of funding - but not to the exclusion of everything else. If we fund ONLY those causes described by EA community as cost-effective, there are huge repercussions to that. We need to think about addressing root causes of issues, including those that are complex and may be expensive to solve, not just individual lives saved per £100k (or if we go for lives/£ then at least factor in WELLBYs as suggested, and make some attempt to consider knock on impacts of funding or not , including the difference between low funding for a cause vs zero funding for a cause).

I'd love to see more posts like this one that ask bold questions challenging existing assumptions - strong upvote!

Thanks for the support, RedTeam!