Note: This post is written in a personal capacity. The views expressed here are our own and do not represent those of any organisation we're affiliated with. We're grateful to Bob Fischer, Tobias Leenaert, Pablo Moleman, Felix Werdermann, and Kevin Xia for their valuable input and feedback, which does not imply endorsement of the arguments presented. While we've done our best to base this post on careful research and reasoning, we don't claim to be experts on this topic. Our aim is not to assert a final conclusion, but to explore an idea we find worth discussing, and we'd be really grateful for any thoughts that might challenge or deepen our understanding.

This post explores whether eating sardines and anchovies could overall result in more good than harm and whether the consumption of these fish can be aligned with the ethics of veganism, despite departing from conventional vegan norms. It examines nutrition, sustainability, and animal ethics, as well as the broader implications for societal progress and animal advocacy. Importantly, it is not an argument for the consumption of fish in general. Fish species differ significantly across key dimensions, and sardines and anchovies stand out in several relevant respects, as will be discussed in detail.

🥣 Health & Nutrition

Uncertainty in Nutrition Science

Nutrition science is one of the least robust areas of research. It involves studying both a highly complex organism (humans) and a highly complex intervention (diet). As a result, it faces several fundamental challenges:

- Long-term studies are observational and therefore cannot reliably separate correlation from causation.

- Diets correlate with lifestyle factors like exercise and income, which cannot be fully controlled for.

- Dietary data is typically based on memory and self-reporting, making it unreliable.

Consequently, robust conclusions are very hard to establish. While a well-planned plant-based diet appears adequate for most healthy adults, it remains uncertain whether avoiding all animal products is optimal, especially with regard to long-term health, where small deficiencies can take decades to manifest and may be hard to reverse. From a nutritional perspective, given that human physiology evolved on an omnivorous diet, it may therefore be prudent to include a small amount of animal products in our diet.

Limitations of Supplementation

While combining a plant-based diet with supplements may be a viable strategy to achieve optimal long-term health outcomes without the inclusion of animal products in principle, it comes with practical limitations:

- Supplements can be expensive and difficult to obtain, especially EPA/DHA and certain carninutrients.

- Many people do not manage to take supplements consistently, limiting the benefits.

Whole foods may offer better nutrient synergy and higher bioavailability than isolated supplements.[1]

- Animal products may contain unknown beneficial compounds that are missing from supplements.

Supplement quality is not subject to regulatory control, raising concerns about safety and efficacy.[2]

Importantly, if people experience health issues on plant-based diets due to suboptimal nutrition, they may abandon the diet altogether and advise others against it. In some cases, they may even publicly criticise veganism in ways that undermine the movement's credibility and reach. Ensuring that people can meet their nutritional needs reliably is therefore not only essential for individual health but also critical to the long-term success of the movement.

Potential Health Benefits of Fish

Observational data from large cohort studies such as the Adventist Health Study 2 and the EPIC-Oxford study show that, although vegans tend to have lower blood pressure[3] and cholesterol levels[4], pescetarians achieve better outcomes than both vegans and vegetarians in several key health metrics, including all-cause mortality[5], colorectal cancer risk[6], and stroke risk[7]. It is further worth noting that these studies focus exclusively on clinical endpoints like mortality and disease incidence, not on functional measures such as subjective well-being or cognitive performance, which may be precisely where some of the advantages of including fish would be most pronounced. More research is needed, but there is good reason to suspect that sardines and anchovies in particular may offer meaningful health benefits: As short-lived fish low on the food chain, they accumulate only minimal levels of mercury, and any microplastics they ingest tend to accumulate in the gut, which is usually removed before consumption. Nutritionally, they offer an abundance of nutrients that are often limited or less bioavailable in plant-based foods. Sardines and anchovies are exceptionally rich in EPA/DHA, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids absent from plant-based foods except for microalgae, and also provide ARA, another long-chain fatty acid virtually exclusive to animal products. Furthermore, they offer highly bioavailable forms of minerals and vitamins often considered critical in plant-based diets, including calcium, heme iron, zinc, selenium, iodine, vitamins A, D3, K2, B3, B7, B12, along with the vitamin-like nutrient choline. They also contain a range of carninutrients such as creatine, taurine, collagen, carnosine, and anserine, which are effectively only found in animal products and are linked to benefits for longevity and cognitive function.[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] Finally, they also represent a highly accessible protein source rich in all essential amino acids, helping to diversify plant-based diets where many high-protein options rely on soy, pea or wheat. Overall, sardines and anchovies effectively address several nutritional challenges common in plant-based diets. The table below summarises key nutritional information.[13]

| Sardines (100 g) | Anchovies (100 g) | Recommended[14] | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | ~208 kcal | ~210 kcal | ~2000–3000 kcal | |

| EPA/DHA | ~1.4 g | ~1.5 g | ~0.5–1 g | Not present in plant-based foods except for microalgae |

| ARA | ~70 mg | ~95 mg | ~100–150 mg | Not present in plant-based foods |

| Calcium | ~382 mg | ~232 mg | ~1000 mg | Limited intake on plant-based diets |

| Iron | ~2.9 mg | ~4.6 mg | ~10–20 mg | More bioavailable than non-heme iron in plant-based foods |

| Zinc | ~1.3 mg | ~2.4 mg | ~10–15 mg | Limited intake on plant-based diets |

| Selenium | ~53 µg | ~37 µg | ~60–70 µg | Limited intake on plant-based diets |

| Iodine | ~30 µg | ~35 µg | ~150–200 µg | No reliable plant-based source |

| Vitamin A | ~32 µg | ~12 µg | ~700–900 µg | More bioavailable than beta-carotene in plant-based foods |

| Vitamin D3 | ~4.8 µg | ~1.7 µg | ~20–50 µg | More bioavailable and effective than D2 in plant-based foods |

| Vitamin K2 | ~20 µg | ~15 µg | ~60–80 µg | More bioavailable and effective than K1 in plant-based foods |

| Vitamin B3 | ~5 mg | ~20 mg | ~13–16 mg | Lower bioavailability in plant-based foods |

| Vitamin B7 | ~10 µg | ~8 µg | ~30–40 µg | Lower bioavailability in plant-based foods |

| Vitamin B12 | ~8.9 µg | ~0.9 µg | ~2.4–4 µg | No reliable plant-based source |

| Choline | ~75 mg | ~85 mg | ~400–550 mg | Limited intake on plant-based diets |

| Creatine | ~0.9 g | ~0.7 g | ~3–5 g | Not present in plant-based foods |

| Taurine | ~120 mg | ~220 mg | ~150–4000 mg | Not present in plant-based foods |

| Collagen | ~1.5 g | ~2 g | ~2.5–15 g | Not present in plant-based foods |

| Carnosine | ~50 mg | ~60 mg | ~500–1000 mg | Not present in plant-based foods |

| Anserine | ~30 mg | ~35 mg | ~500–750 mg | Not present in plant-based foods |

| Protein | ~26 g | ~29 g | ~1.2–1.6 g/kg of body weight | More balanced amino acid profile than most plant-based foods |

🌍 Sustainability

Resources and Emissions

Sardines and anchovies are always wild-caught, as their natural abundance, fast reproductive cycles, and shoaling behaviour make aquaculture economically unviable. As a result, their production footprint is remarkably low:

- No land is required, since they are always caught in the wild.

- No freshwater is required, apart from the minimal amounts used for standard cleaning and processing.

- No feed is required, since they feed naturally in the wild, primarily on plankton.

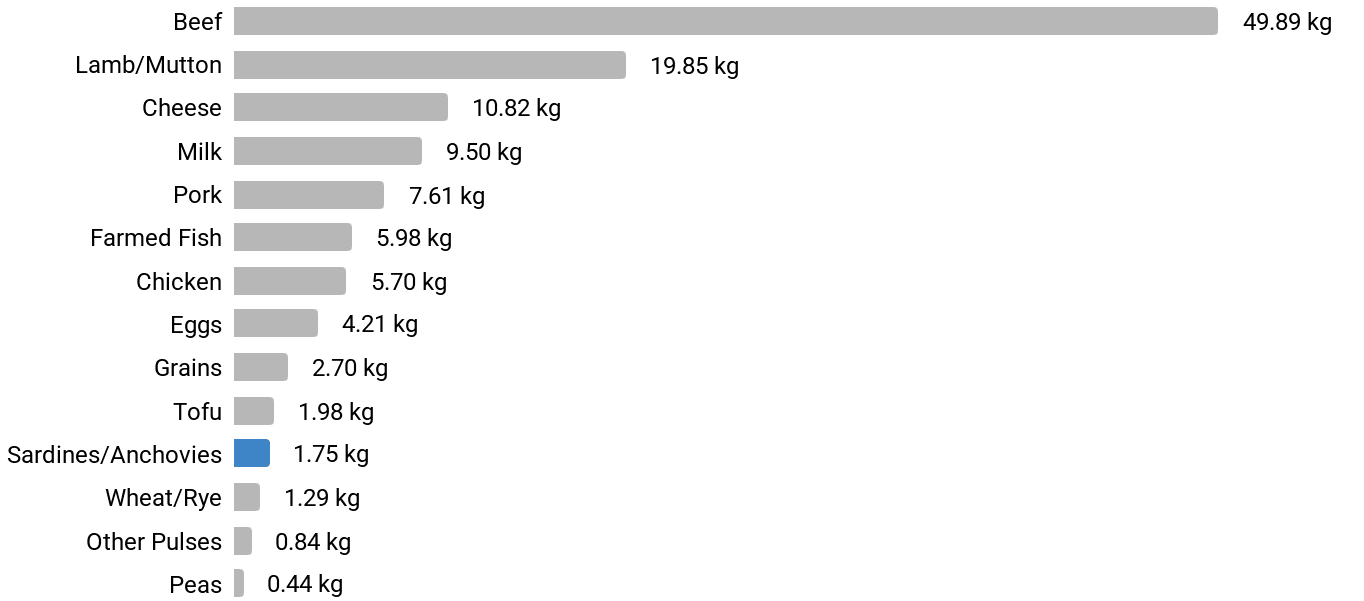

GHG emissions are very low compared to other protein sources, for the most part because they are not farmed. See below for the GHG emissions per 100 gram of protein for various protein sources.[15] [16] [17]

Fish Populations

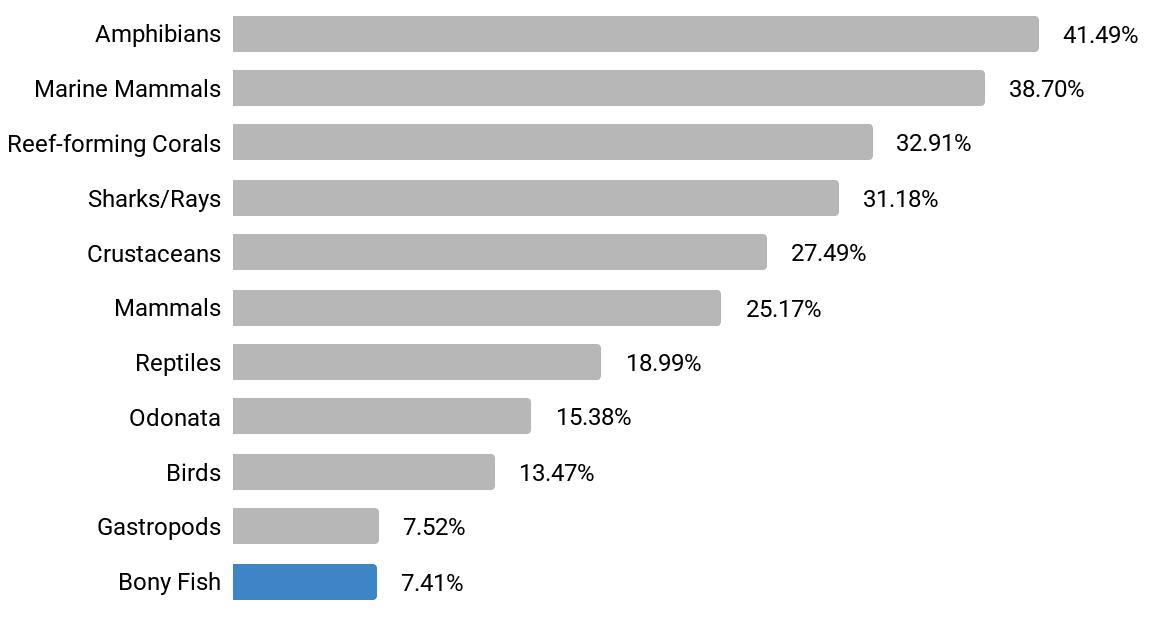

Sardines and anchovies are broadcast spawners with short lifespans and high reproductive rates, which makes them highly resilient to fishing pressure and has ensured their consistent abundance worldwide.[18] On top of that, their populations are well-managed in European waters through annually adjusted and effectively enforced catch quotas.[19] While sustained increases in demand could potentially create political pressure to raise them, especially when short-term economic goals take priority, these quotas are aligned with the long-term interests of the fishing industry and therefore generally supported by it. Most sardines and anchovies are currently used for aquaculture feed and pet food, but the fact that many feed producers are already shifting to plant-based alternatives shows that such a transition is feasible.[20] Since total catch volumes are capped, increased human consumption is therefore unlikely to raise fishing pressure but rather redirect use from feed to food. From a food justice perspective, it is important to note that rising European demand would overwhelmingly be met by local, cost-efficient EU fisheries, since fisheries in the Global South primarily produce fishmeal for export rather than food for human consumption. Overall, the greatest threat to sardine and anchovy populations is not fishing, but climate change, which disrupts their food supply and spawning patterns through changes in ocean temperatures and currents. Even so, only a small fraction of bony fish species are considered threatened with extinction, reflecting the resilience of species like sardines and anchovies. See below for the estimated percentage of threatened species by different species groups.[21]

Ecological Impacts

Sardines and anchovies are a key food source for many marine predators. While regulated fishing can help maintain their populations, current management practices often disregard the impacts on dependent predator species. However, many of these predators are highly mobile, have broad diets, and evolved alongside the natural boom and bust cycles of sardines and anchovies, allowing them to adapt and switch to alternative prey when necessary.[22] Wild sardine and anchovy fishing also results in very low bycatch.[23] As pelagic fish that swim in dense shoals near the surface, they are caught with purse seine nets rather than bottom trawls, avoiding seabed damage and minimising the risk of plastic pollution through ghost gear.

🐟 Animal Ethics

Moral Weights

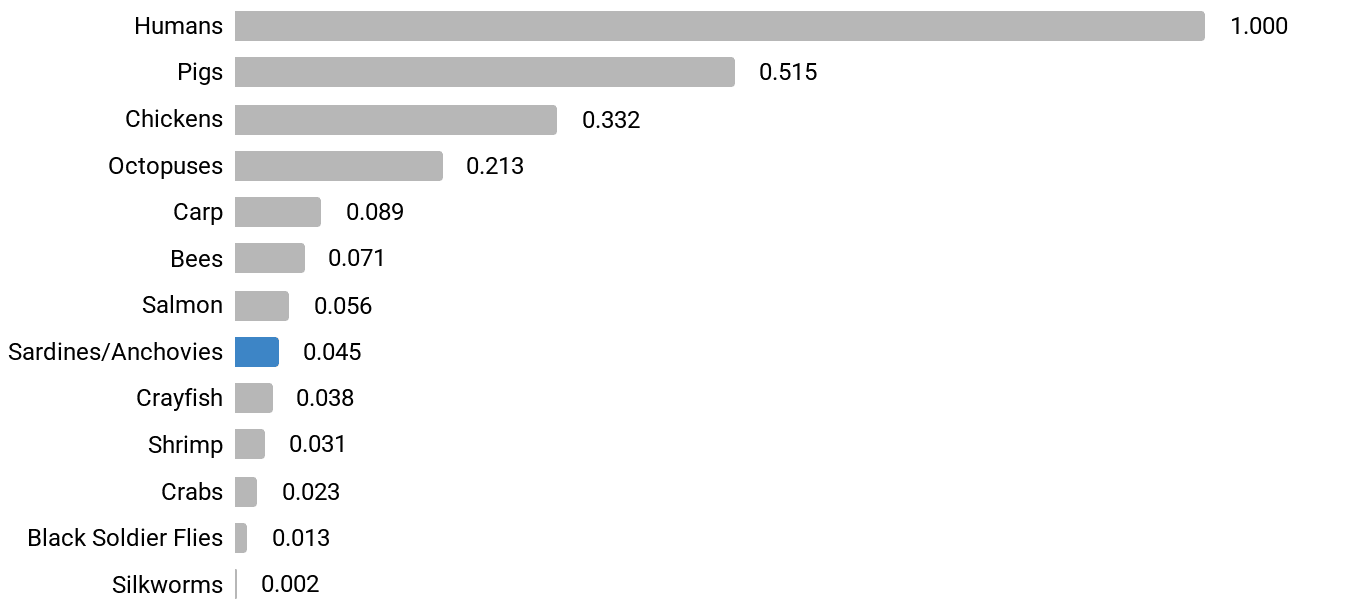

Rethink Priorities assesses the moral weights of different sentient species by estimating how wide their ranges of possible positive and negative experiences are, using factors like brain structure, learning ability, behavioural flexibility, emotional capacity, and social behaviour.[24] Although sardines and anchovies have not been directly assessed, it is possible to make an informed estimate on the basis of their simple, instinct-driven behaviours:

- No pair bonding or parental care (broadcast spawners)

- No complex hunting behaviour (filter feeders)

- Limited navigation and learning capabilities

Therefore, sardines and anchovies appear to rank below salmon, who famously navigate thousands of kilometres back to their natal streams to spawn and exhibit complex mating strategies like nest-building and male competition for mates. However, their vertebrate nervous systems, capacity for pain processing, and social behaviours such as shoaling suggest sardines and anchovies may be more cognitively and behaviourally sophisticated than crayfish. In accordance with this, their welfare range is estimated to be ~0.045[25], below salmon but above crayfish, which can serve as a proxy for their moral weight. See below for the welfare range estimates by Rethink Priorities.[26]

While the small body size of sardines and anchovies means that many individuals must be killed to produce a given amount of food, thereby scaling up the moral weight, a meaningful moral cost calculation should extend beyond these direct first-order consequences to account for indirect higher-order consequences, especially given that all food production invariably involves some level of collateral damage, as will be discussed further on.

Fishing vs. Crop Deaths

Crop production kills a large number of animals, many of which have a much higher moral weight than sardines and anchovies. Field mice are crushed by tractors, bird nests are destroyed by harvesters, fish are poisoned by fertiliser run-off, and countless insects are killed by pesticides and other agricultural practices. While reliable data on crop deaths is extremely limited[27], it is plausible that these crop deaths may carry a higher total moral cost than fishing sardines and anchovies. On the other hand, wild animals die constantly in nature due to predation, starvation, and disease, and few survive to old age. It is therefore unclear whether crop deaths cause more suffering than would otherwise occur in nature.

Fishing vs. Natural Deaths

Fishing sardines and anchovies inevitably causes deaths, but what matters ethically is how these compare to the deaths the animals would otherwise face in nature. Sardines and anchovies lay tens to hundreds of thousands of eggs each year, yet fewer than one in a thousand survive to adulthood. When they do, most ultimately die through predation, starvation, or disease. Predation involves sardines and anchovies being pursued, exhausted, and eventually killed by dolphins, large fish, and seabirds, causing both severe mental and physical strain. While the final phase, when the fish are tightly packed into dense formations known as bait balls, may last only several minutes, the strain often begins much earlier during extended periods of chase and herding. Once caught, they are typically swallowed whole and remain alive in the predator's stomach for around 20 minutes, during which they suffocate or are slowly digested by acids and enzymes.[28] Meanwhile, starvation and disease may lead to significantly longer periods of intense suffering, marked by a slow and progressive decline. Commercial fishing on the other hand uses purse seine nets to encircle entire shoals and haul them aboard within 90 to 120 minutes.[29] This usually takes place at night, when the darkness likely reduces stress levels in the fish, as they are calmer and less alert. During the hauling phase, many fish die from crushing as the net tightens, while others die from asphyxiation due to falling oxygen levels. Since direct evidence comparing the subjective distress caused by fishing and natural deaths is limited, it remains unclear which form of death causes greater overall suffering. While human morality distinguishes between intentional killing and agentless dying, this distinction is meaningless from the perspective of the fish. What matters to them is not our intentions, but their own experience, and our thoughts and feelings make no difference to their reality.

Species Survival

It is uncertain whether wild animals currently live net positive lives, but they may have the potential to do so in the future, especially if we develop better ways to reduce their suffering. Since the future will almost certainly contain vastly more individuals than the present due to the many generations yet to come, ensuring the continued existence and flourishing of wild animals could have a substantial positive impact. This suggests that our ethical concern should extend beyond individual animals to the long-term survival of species and the ecosystems that support them. Biodiversity plays a key role in maintaining ecosystem resilience by providing redundancy and adaptability. As it declines, ecosystems become more fragile, raising not only the risk of widespread species loss but also the risk of human extinction, given our dependence on functioning ecosystems. Accordingly, preserving biodiversity may play a critical role in safeguarding the long-term future of humanity. Currently, the leading driver of biodiversity loss is land use change. Given that complex life evolved over billions of years and that extinctions are likely irreversible, there is a strong case for urgent action to prevent further species loss. It may therefore be ethically preferable to prioritise foods that minimise land use change, such as sardines and anchovies.

💡 Societal Implications

Moral Progress

Principles like "don't eat sentient beings" are heuristics that fit within a rights-based moral framework and aim to minimise suffering. Even in cases where they fail to do so due to unintended harmful higher-order consequences, they can still reinforce moral concern for sentient beings, as our moral intuitions are guided more by perceived than by actual suffering: The harm to a fish when we eat it is emotionally more salient than its counterfactual natural death as well as the harm to wild animals caused by land use change or crop deaths when we eat plant-based foods. Given this psychological predisposition, adhering to a rights-based heuristic can promote moral circle expansion and help establish a value system that extends moral consideration to all sentient beings. This is arguably the main reason why conventional veganism prioritises purity at the level of first-order consequences. Establishing fundamental rights for sentient beings may also positively influence how future superintelligent AIs will treat humans and other sentient life, should they adopt prevailing human values. However, rigid adherence to a rights-based heuristic can oversimplify complex realities and undermine its very purpose by overlooking that deviating from purity at the level of first-order consequences can lead to a net positive outcome in some cases. A commitment to optimise outcomes based on a careful assessment of all downstream consequences may therefore better serve the presumed core ethical goal of veganism: minimising the suffering of sentient beings. This may support including certain animals like sardines and anchovies in our diet, provided under conditions that result in less overall harm. More broadly, such a pragmatic approach may help build a more compelling moral framework grounded in impartial truth-seeking and commitment to doing the most good, in alignment with the principles of effective altruism.

Food System Change

Producing plant-based foods currently causes significant harm to animals, particularly through land use change and potentially also through crop deaths. However, technological progress raises the possibility that plant agriculture might one day cause minimal harm to animals, perhaps even none. Adopting a fully plant-based diet and thereby aligning with this long-term vision may help accelerate the transition toward it. In the meantime, sardines and anchovies could be the more ethical choice during this transition, especially since they are much cheaper than plant-based protein sources combined with supplements. This frees up financial resources that can be donated for greater impact toward that vision and also avoids moral licensing, a phenomenon in which an ethical choice leads to a sense of moral satisfaction, thereby reducing the motivation to take further meaningful action, such as donating. Although transitional solutions do carry a risk, as eating habits tend to become entrenched over time, technological progress in alternative proteins such as cellular agriculture could enable a future shift away from eating animals like sardines and anchovies without requiring major behavioural change.

📢 Effective Advocacy

Pragmatism vs. Purity

A simple message like "I'm vegan" is both powerful and easy to communicate, but may alienate those who see it as too rigid or extreme. A more nuanced stance like "I consider myself vegan but eat sardines and anchovies" may confuse or irritate others, especially in settings where time or openness for deeper discussion is limited. Yet in the right context, it can spark curiosity and lead to a more meaningful dialogue, as thoughtful nuance and rational trade-offs can signal open-mindedness and strengthen credibility as a non-dogmatic advocate. Especially since most people are more concerned with the scale of animal agriculture and its consequences than with the idea of eating animals per se, a philosophy that allows for the consumption of a few carefully considered animal products may resonate with a broader audience and thereby inspire more people to take meaningful steps toward minimising animal suffering, even if they don't entirely adopt a conventional vegan lifestyle. At the same time, such nuance may undermine credibility in the eyes of those who view deviations from conventional veganism as morally inconsistent, and constantly adjusting the message to the audience can strain authenticity and lead to decision fatigue.

Diversity vs. Unity

Deviating from conventional veganism may risk weakening the movement's ability to build coherent narratives and foster a strong collective identity. A clear and consistent message like "don't eat animals" can be a powerful tool for social change. When repeated by many people over time, it helps shape public perception and gives supporters a sense of belonging. Movements often rely on these dynamics to establish momentum, especially when they are still small. At the same time, it is unlikely for a one-size-fits-all message to work for everyone, as different messages resonate with different people. For someone who does not view eating animals as inherently wrong or is not convinced by conventional veganism for other reasons, the idea that eating sardines and anchovies may cause less harm than many plant-based foods could draw them in rather than push them away. Therefore, using a diversity of approaches tailored to different audiences may help reach more people and ultimately advance the movement's goals more effectively.

👉 Conclusion

Reconsidering the ethics of eating sardines and anchovies through a pragmatic lens suggests that avoiding all animal products may not always be the most effective way to minimise harm. Rather than focusing only on the first-order consequences of our food choices and striving for purity at that level, it may better align with the core values of veganism to consider the full range of downstream consequences and make choices that produce the greatest net benefit for sentient beings. Sardines and anchovies provide exceptional nutritional value and, under the right conditions, may carry a lower environmental and moral cost than many plant-based foods. Including these small, short-lived fish in an otherwise plant-based diet can help meet nutritional needs more reliably, ease the ecological burden of food production, and minimise harm to animals with higher sentience. When approached thoughtfully and communicated with care, this pragmatic approach could broaden the appeal of ethical eating and support the long-term goals of the animal advocacy movement. Therefore, eating sardines and anchovies may not only be ethically justifiable but even potentially preferable as a transitional strategy toward a more sustainable and more compassionate food system.[30]

Edit (10 July 2025): Updated the description of the purse seine fishing process to reflect more realistic estimates of its duration, based on feedback by Sagar K Shah. This doesn't change the broader conclusions, but the earlier version gave a misleading impression and has been corrected accordingly. The revised estimate introduces more uncertainty about whether purse seine fishing causes less overall harm than natural death, and this remains an open question.

Edit (15 July 2025): Removed the claim that sardines and anchovies accumulate only minimal levels of PCBs, based on feedback by Nunik. Given the lack of robust evidence, the original statement was overly optimistic. This does not affect the overall health assessment of sardines and anchovies, as health authorities generally consider their nutritional benefits to outweigh the potential risks from PCBs. Consumers can also reduce potential exposure by choosing sardines and anchovies sourced from less polluted regions.

- ^

Jacobs, D. R. J. Jr, Gross, M. D., & Tapsell, L. C. (2009). Food synergy: An operational concept for understanding nutrition. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(5), 1543S–1548S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736B

- ^

Although supplement quality is not regulated, some producers choose to conduct independent laboratory tests for both nutrient content and contaminants, and make the results publicly available.

- ^

Appleby, P. N., Davey, G. K., & Key, T. J. (2002). Hypertension and blood pressure among meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans in EPIC-Oxford. Public Health Nutrition. 2002;5(5):645-654. https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2002332

- ^

Bradbury, K. E., Crowe, F. L., Appleby, P. N., Schmidt, J. A., Travis, R. C., & Key, T. J. (2014). Serum concentrations of cholesterol, apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein B in a total of 1694 meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 68, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.248

- ^

Orlich, M. J., Singh, P. N., Sabaté, J., Fan, J., Sveen, L., Bennett, H., Jaceldo-Siegl, K., Fraser, G. E., & Knutsen, S. (2013). Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(13), 1230–1238. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473

- ^

Orlich, M. J., Singh, P. N., Sabaté, J., Jaceldo‑Siegl, K., Fan, J., Knutsen, S., Beeson, W. L., & Fraser, G. E. (2013). Vegetarian dietary patterns and the risk of colorectal cancers. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(5), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.59

- ^

Tong, T. Y. N., Appleby, P. N., Bradbury, K. E., Perez‑Cornago, A., Travis, R. C., Clarke, R., & Key, T. J. (2019). Risks of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in meat eaters, fish eaters, and vegetarians over 18 years of follow-up: results from the prospective EPIC-Oxford study. BMJ, 366, l4897. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4897

- ^

Avgerinos, K. I., Spyrou, N., Bougioukas, K. I., & Kapogiannis, D. (2018). Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Experimental Gerontology, 108, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2018.04.013

- ^

Singh, P., Gollapalli, K., Mangiola, S., Schranner, D., Yusuf, M. A., Chamoli, M., Shi, S. L., Lopes Bastos, B., Nair, T., Riermeier, A., Vayndorf, E. M., Wu, J. Z., Nilakhe, A., Nguyen, C. Q., Muir, M., Kiflezghi, M. G., Foulger, A., Junker, A., Devine, J., … Yadav, V. K. (2023). Taurine deficiency as a driver of aging. Science, 380(6650), 1028–1033. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn9257

- ^

Koizumi, S., Inoue, N., Sugihara, F., & Igase, M. (2020). Effects of collagen hydrolysates on human brain structure and cognitive function: A pilot clinical study. Nutrients, 12(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010050

- ^

Boldyrev, A. A., Aldini, G., & Derave, W. (2013). Physiology and pathophysiology of carnosine. Physiological Reviews, 93(4), 1803–1845. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00039.2012

- ^

Caruso, G., Godos, J., Castellano, S., Micek, A., Murabito, P., Galvano, F., Ferri, R., Grosso, G., & Caraci, F. (2021). The therapeutic potential of carnosine/anserine supplementation against cognitive decline: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Biomedicines, 9(3), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9030253

- ^

Nutrient values are taken from the USDA database and peer-reviewed studies where available. Where no direct data exists, estimates are based on comparable fish species, typical muscle or organ composition, or published averages from nutritional literature.

- ^

Recommended daily intake levels are intended to reflect the best available estimates for optimal long-term health outcomes in healthy adults. They are based on guidance from health authorities such as EFSA or NIH, as well as expert recommendations from leading voices in nutrition science. While no universal consensus exists, the figures presented are meant to offer orientation. Especially for ARA and the carninutrients, the suggested intakes remain highly speculative and require further research.

- ^

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987–992. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216

- ^

Hilborn, R., Banobi, J., Hall, S. J., Pucylowski, T., & Walsworth, T. E. (2018). The environmental cost of animal source foods. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 16(6), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1822

- ^

Post-harvest GHG emissions for sardines and anchovies are estimated to add 40% to landing-site emissions, based on typical life-cycle assessment data.

- ^

Hilborn, R., Buratti, C. C., Díaz Acuña, E., Hively, D., Kolding, J., Kurota, H., Baker, N., Mace, P. M., de Moor, C. L., Muko, S., Osio, G. C., Parma, A. M., Quiroz, J.‑C., & Melnychuk, M. C. (2022). Recent trends in abundance and fishing pressure of agency‑assessed small pelagic fish stocks. Fish and Fisheries, 23(6), 1313–1331. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12690

- ^

Hilborn, R., Amoroso, R. O., Anderson, C. M., Baum, J. K., Branch, T. A., Costello, C., de Moor, C. L., Faraj, A., Hively, D., Jensen, O. P., Kurota, H., Little, L. R., Mace, P., McClanahan, T., Melnychuk, M. C., Minto, C., Osio, G. C., Parma, A. M., Pons, M., … Ye, Y. (2020). Effective fisheries management instrumental in improving fish stock status. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(4), 2218–2224. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909726116

- ^

Majluf, P., Matthews, K., Pauly, D., Skerritt, D. J., & Palomares, M. L. D. (2024). A review of the global use of fishmeal and fish oil and the Fish In:Fish Out metric. Science Advances, 10(42), eadn5650. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adn5650

- ^

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. (E. Brondizio, S. Díaz, J. Settele, & H. T. Ngo, Eds.) [Report]. IPBES Secretariat. https://ipbes.net/global-assessment

- ^

Hilborn, R., Amoroso, R. O., Bogazzi, E., Jensen, O. P., Parma, A. M., Szuwalski, C., & Walters, C. J. (2017). When does fishing forage species affect their predators? Fisheries Research, 191, 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2017.01.008

- ^

Ruiz, J., Louzao, M., Oyarzabal, I., Arregi, L., Mugerza, E., & Uriarte, A. (2021). The Spanish purse-seine fishery targeting small pelagic species in the Bay of Biscay: Landings, discards and interactions with protected species. Fisheries Research, 239, 105951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2021.105951

- ^

Rethink Priorities. (2022, November 1). An introduction to the Moral Weight Project. https://rethinkpriorities.org/research-area/an-introduction-to-the-moral-weight-project/

- ^

This estimate as well as the published welfare ranges by Rethink Priorities should be treated with caution and ideally complemented by a sensitivity analysis to account for uncertainty.

- ^

Rethink Priorities. (2023, January 23). Welfare Range Estimates. https://rethinkpriorities.org/research-area/welfare-range-estimates/

- ^

Fischer, B., & Lamey, A. (2018). Field Deaths in Plant Agriculture. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 31, 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9733-8

- ^

Michael St Jules. (2024, June 9). Being swallowed live is a common way for wild aquatic animals to die. Effective Altruism Forum. https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/i4KbJubBJfsaNgAJP/being-swallowed-live-is-a-common-way-for-wild-aquatic

- ^

Marçalo, A., Marques, T. A., Araújo, J., Pousão-Ferreira, P., Erzini, K., & Stratoudakis, Y. (2006). Sardine (Sardina pilchardus) stress reactions to purse seine fishing. Marine Biology, 149(6), 1509–1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-006-0277-5

- ^

While this essay focuses on sardines and anchovies, the arguments presented may also apply to other small pelagic fish that are short-lived, broadcast-spawning, low on the food chain, wild-caught with minimal bycatch, and behaviourally simple with limited sentience.

Interesting!

On the other hand, sardines really are very small, and I reckon you'd need on the order of 100x as many sardines as you'd need salmons to get the same amount of calories. I wonder how many small animals would die to produce the amount of calories of plant-based food you'd get from a sardine? I'd guess <<0.1, but I'd be interested in seeing estimates here as it seems pretty cruxy.

That section states

I thought I'd expand on this claim a bit, as I agree with @Erich_Grunewald 🔸 it seems cruxy.

Ultimately I agree, though if I were deriving my opinion sole... (read more)