Note: This post was crossposted from the Open Philanthropy Farm Animal Welfare Research Newsletter by the Forum team, with the author's permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post.

People can’t get enough protein. Fully 61% of Americans say they ate more protein last year — and 85% intended to eat more this year. Last week, dairy giant Danone said it can’t keep up with US demand for its high-protein yogurt. Other food makers are rushing to pack protein into everything from Doritos to Pop-Tarts.

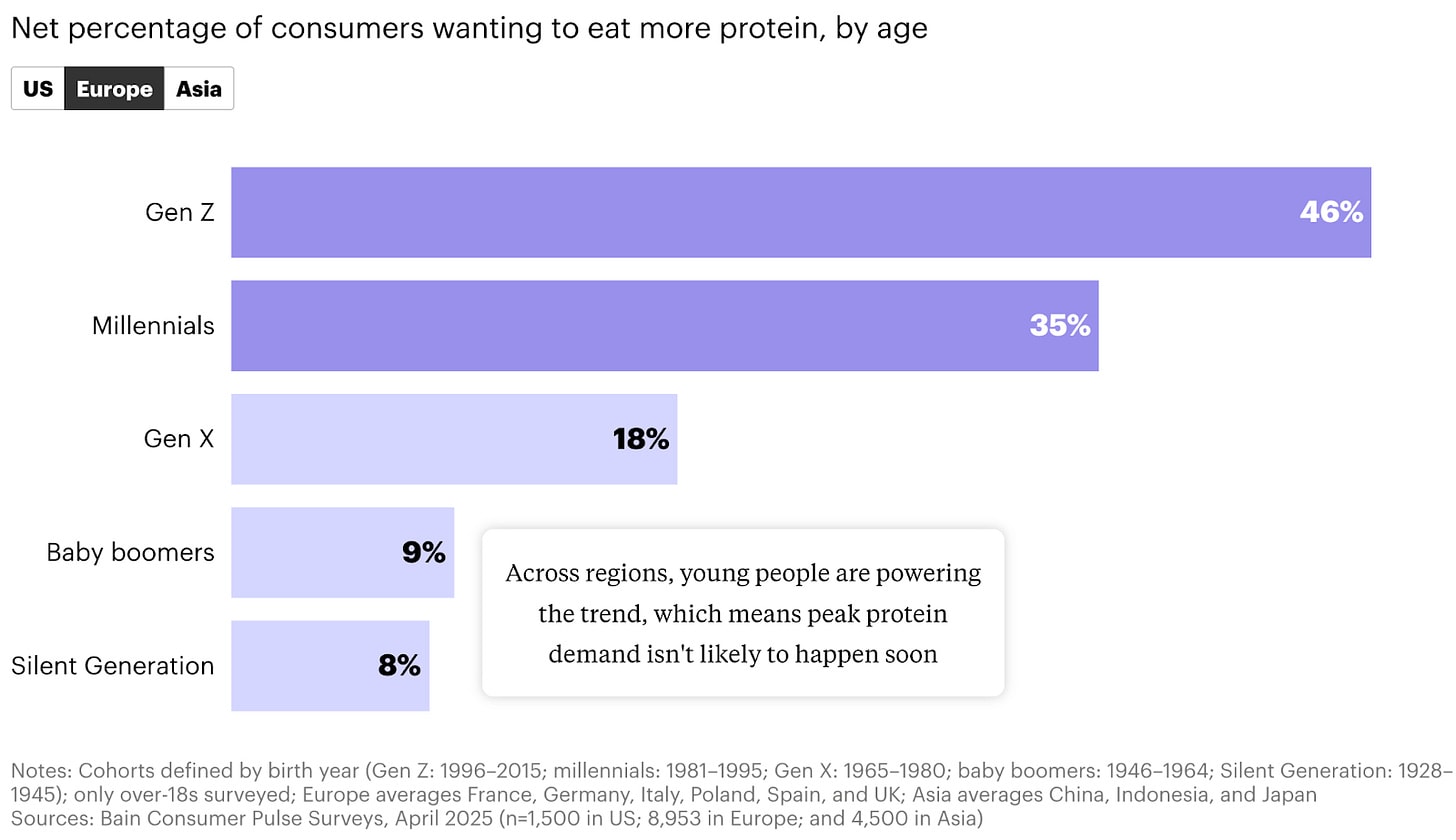

The craze is global. The net percentage of Europeans wanting more protein has more than doubled since 2023, driven by protein-hungry Brits, Poles, and Spaniards. (The epicurean French and Italians remain holdouts.) Chinese per capita protein supply recently overtook already-high American levels.

Young people are leading the charge. Across Asia, Europe, and the US, most Gen Z’ers want more protein, suggesting this trend may persist. In one recent British university survey, “protein” was the top reason students gave for not giving up meat. Doctors are also telling the 6 - 10% of Americans now taking GLP-1 weight loss drugs to eat more protein to prevent muscle loss.

This is bad news for animals, who supply two thirds of the protein Americans eat. It’s especially bad for the smallest animals — chicken, fish, and shrimp — who happen to be the most protein-dense. While global per capita consumption of beef and pork is slowly falling, consumption of chicken, eggs, and seafood is surging.

So what can we do? There are three broad options: push less protein, more plant protein, or less cruel animal proteins. Let’s take each in turn.

Let the people eat protein

Most Americans likely already eat enough protein. U.S. dietary guidelines recommend about 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight daily — roughly 50 grams for the average person. Yet the American food system now churns out more than twice that amount per person.

Protein influencers dismiss these guidelines as obsolete. The top health podcaster, Andrew Huberman, tells his millions of listeners to eat 2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight daily. But a recent federally-commissioned review of all studies from 2000 to 2024 found little reason to update the guidelines. While it was ultimately “inconclusive,” its authors mostly seemed unsure what to recommend within a range of 0.7 to 1 gram per kilogram daily.

Still, the anti-protein fight feels futile. Protein has such a positive halo — Strength! Energy! Vitality! — that opposing it feels a bit like being anti-puppies. Indeed, I sometimes wonder if decades of vegan anti-protein advocacy has mostly convinced people that vegans don’t get enough protein.

There’s no alternative to alternative proteins

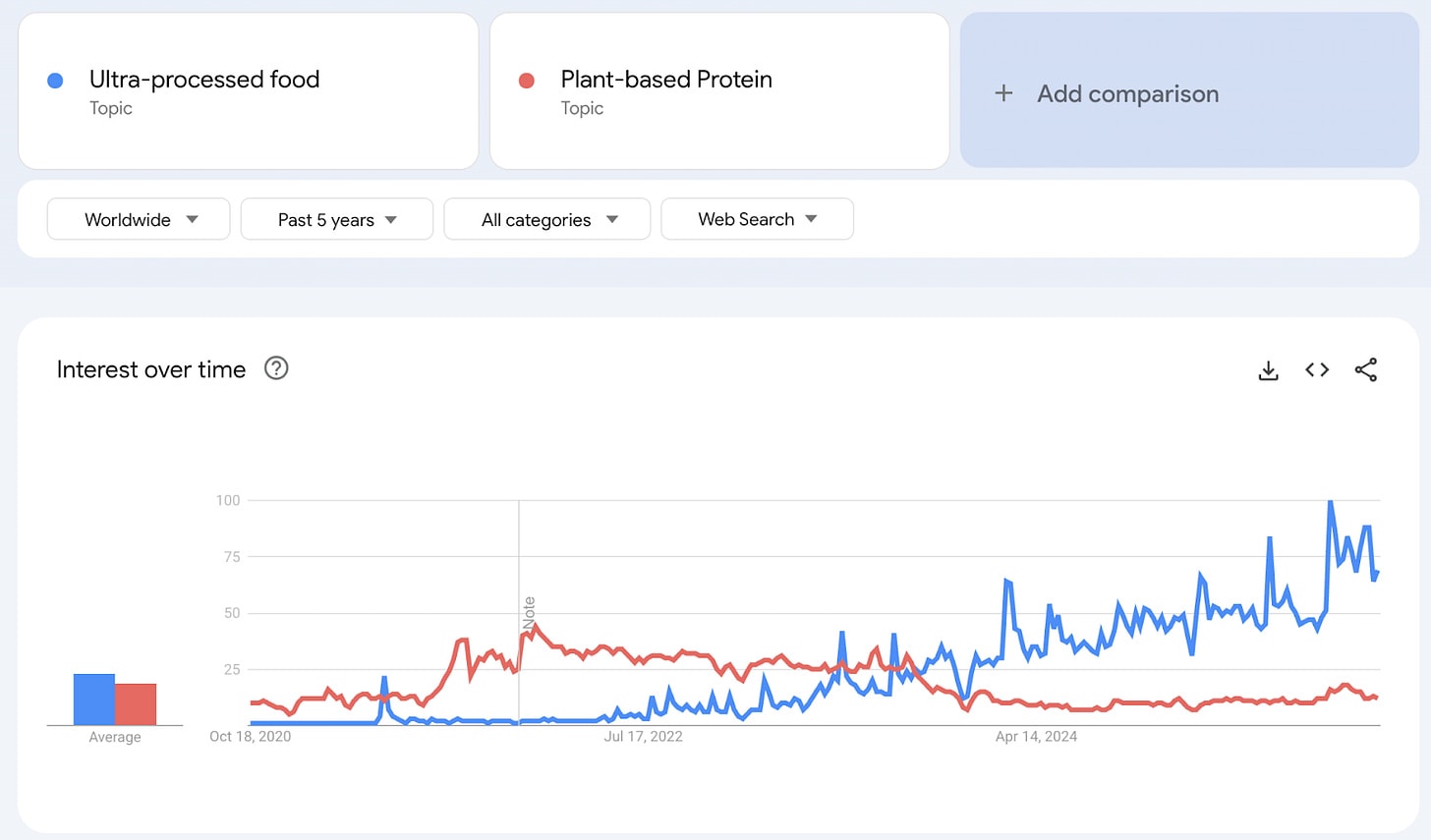

One more promising strategy is to meet the protein craze with plants. For a moment, this was working. Plant protein sales surged from 2020-22, propelled by Beyond and Impossible product launches and The Game Changers documentary. Then they stalled and, in many markets, declined.

One likely reason: the backlash against “ultra-processed” foods. Google searches for plant-based protein have fallen right as searches for ultra-processed food have spiked (see chart). In a 2024 survey of 10,000 Europeans, 54% agreed that “I avoid plant-based meat replacements because they are ultra-processed.”

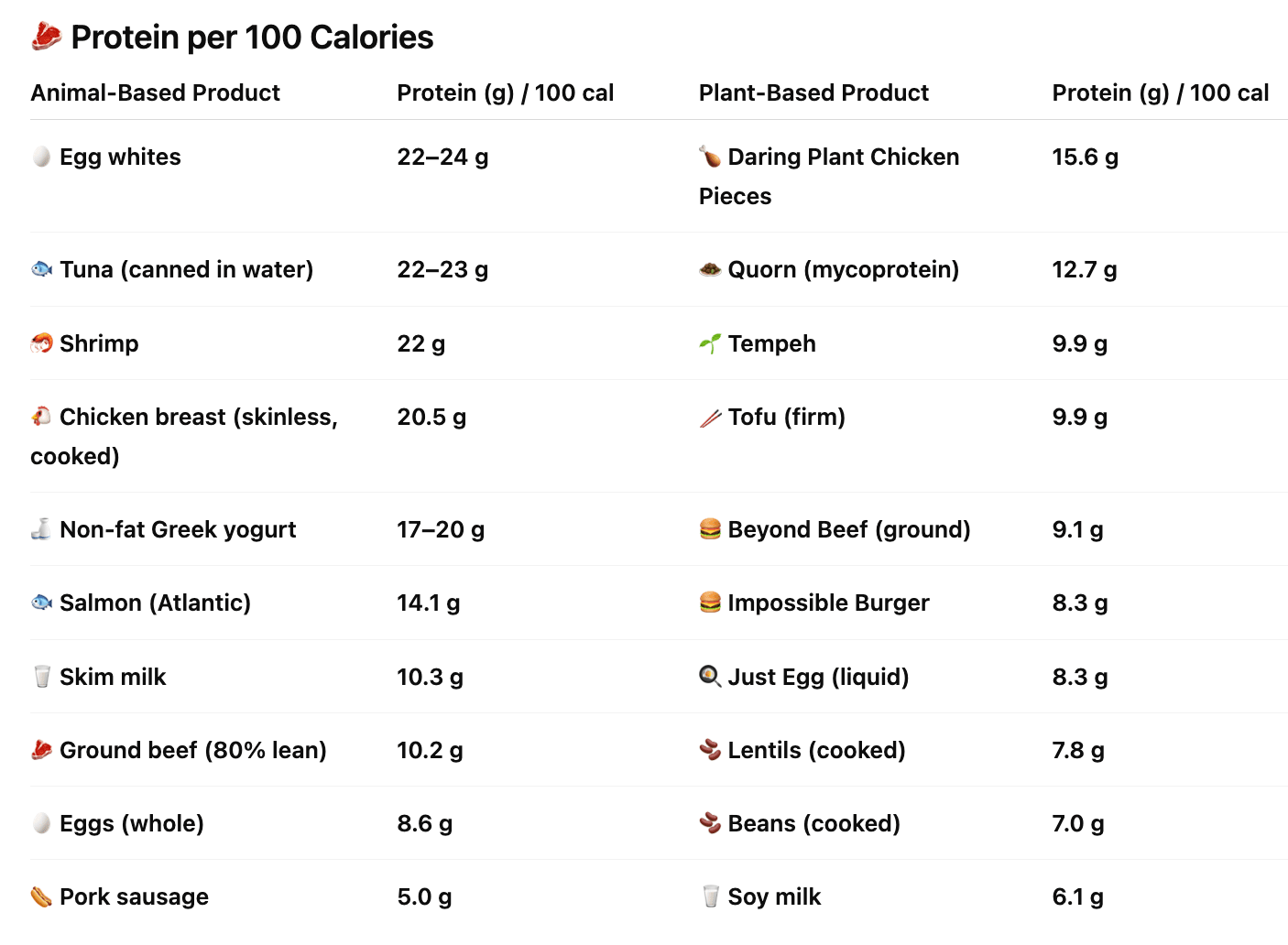

The anti-processing panic has some advocating a return to whole plant proteins: tofu, beans, lentils. I’m a fan. But most Americans aren’t: tofu was the fourth most disliked food in a recent YouGov survey. And beans and lentils are almost three times less protein-dense than tuna, shrimp, and chicken breast — a dealbreaker for protein maximizers.

That’s why we need alternative proteins. Extracting and concentrating protein from peas and soybeans creates products that are tastier and more protein-dense than whole plants. This will always require processing. So we need to find a better way to market processed plant proteins. I don’t know how to do this; I hope to write more on the challenge next year.

For now I’ll just note that people are confused about processing — and the “experts” are part of the problem. That same 2024 survey of 10,000 Europeans, run by the EU- and FAO-backed EIT Food group, categorized chicken as “unprocessed” and plant-based chicken as “ultra-processed.” But both products come from processing plants. And both start as soybeans, corn, and additives. The main difference is that the chicken version includes an extra layer of “unnatural” processing — inside the stomach of a Franken-chicken confined in an animal factory.

Some proteins are crueler than others

Still, most people won’t be sold on just eating plants anytime soon. So we need to present people with less cruel animal protein options. There are two ways to identify these: by species or conditions.

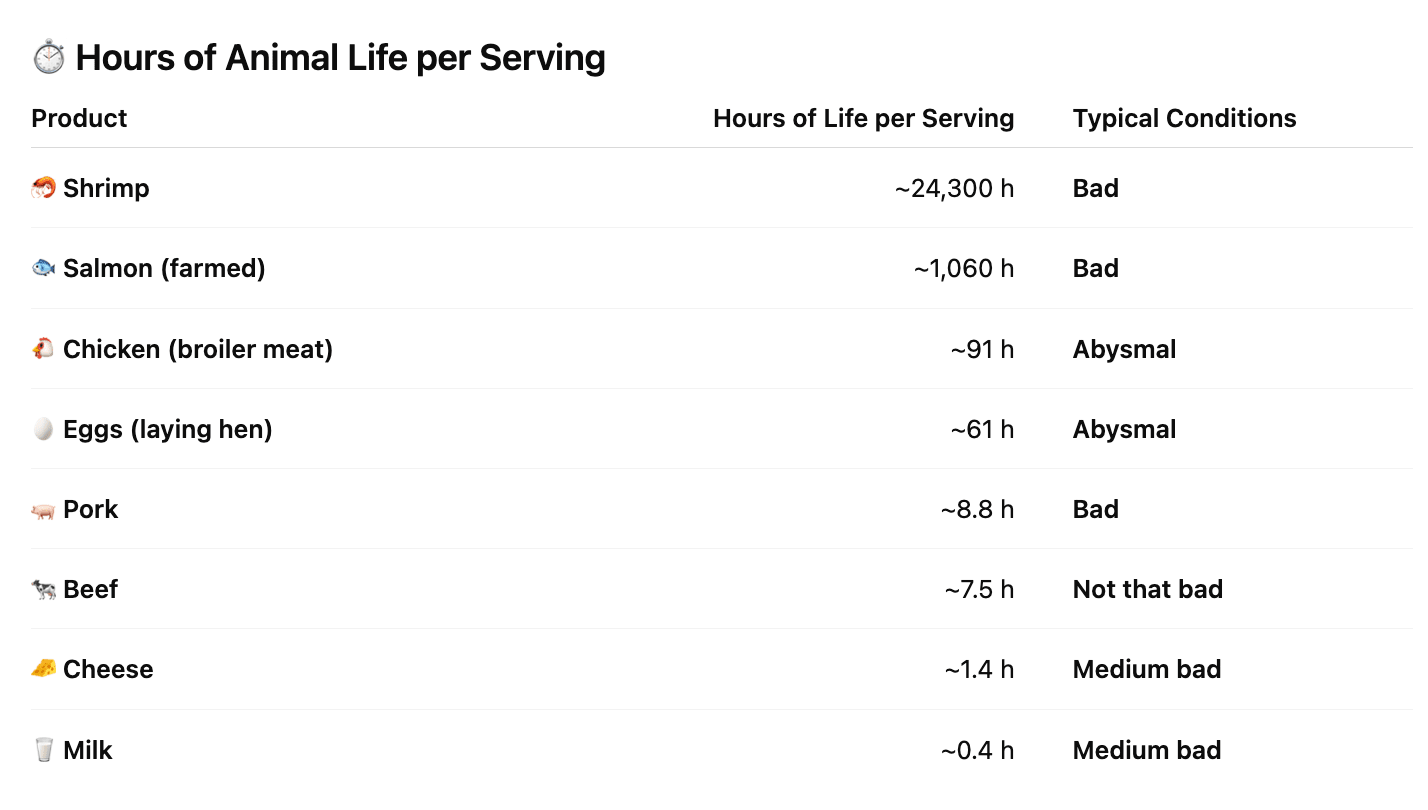

The choice of species likely matters more. Smaller animals typically suffer longer in worse conditions per serving for three reasons:

- Size: a cow yields far more beef than a chicken yields meat. Though chickens grow faster, a serving of chicken still requires over 10x more days of animal suffering than beef. Due to dairy cows’ efficiency, a serving of milk requires even less time (see chart below).

- Lifespan: farmed fish like salmon grow slowly, living 1-2 years — much longer than most farmed animals. They’re also small. So one salmon serving can require over 1,000 hours of animal suffering. (Wild-caught salmon suffers less, but buying it likely increases demand for farmed salmon since wild stocks are supply-limited.)

- Typical conditions: smaller animals are treated worse because they’re less valuable and more replaceable. As one indicator: US pre-slaughter mortality rates — annualized to account for different lifespans — are 2-6% for beef cattle, 18% for pigs, and 36% for broiler chickens.

This counterintuitively suggests animal advocates may be wrong to decry carnivore influencers promoting beef. If the alternative is chicken, beef is better.

But most people won’t give up chicken, eggs, and fish. So we need less cruel versions of them. There may be an opening here: many protein influencers who promote meat, like Joe Rogan, also condemn factory farming. The appetite for change is there. The problem is that the market isn’t.

Corporate campaigns have been our most powerful tool for fixing that. They don’t just lift the floor for welfare; they raise the ceiling for better products. As cage-free has become the new default in Europe and the US, free-range and pasture-raised eggs have taken off. Today, 11% of US hens, 16% of European hens, and 72% of British hens have outdoor access (at least when avian flu doesn’t close the doors). Pasture-raised brands like Vital Farms are booming.

Other sectors face bigger obstacles, exacerbated by fraudulent labels. When Tyson can sell factory-farmed chickens as “all-natural” and “premium” for $5 apiece, honest producers of genuinely naturally-raised birds can’t compete. Governments could fix this with honest labeling laws, but few have shown much interest in doing so.

That makes private certifications critical. In Germany and the Netherlands, nearly all retail chicken carries Haltungsform or Beter Leven labels. Both use tiered systems that let retailers gradually raise standards while offering credible premium options. In the US and UK, Global Animal Partnership and RSPCA Assured have tried to build similar schemes, only to be attacked by PETA and Animal Rising.

This is shortsighted. With protein demand surging, we need every tool available. Some people (including me) will choose plant proteins. Some will stick mostly to beef and dairy. But most will eat chicken, eggs, and fish regardless. We need to give them better choices.

Protein isn’t the enemy — cruelty is. That’s actually good news. We don’t know how to get people to eat less protein. But we have proven ways to reduce the cruelty behind the protein they consume. We should use all of them.

I don't think it's wise to redefine what should count as an ultra-processed food to suit your agenda. When people talk about UPFs, they're clearly concerned about chemical additives like emulsifiers, stabilizers, colorings, and artificial sweeteners. As unlike wild chickens as today's broiler chickens are, they don't contain those things and don't pose the same health risks that those things do. In that light, I found this discrediting:

I hope others don't repeat it. It may well be that the general concept of UPFs is nonsense — and if so, people should argue for that, or that Beyond/Impossible doesn't qualify under a reasonable definition — but people know what they have in mind when they use the term and will know you're not respecting their concerns when you try to be clever like this.

Totally fair feedback. I agree that I should probably have just argued that the general concept of UPFs is nonsense. My sense is that most of the evidence for the harms of UPFs is correlational and based on studies that look at high consumption of fast food and other junk food that we know is based for you based on high sugar, salt, and caloric levels. (I.e. where you don't need to add UPF to explain why they'd be unhealthy.)

My sense is also that the evidence for food additives like emulsifiers, stabilizers, colorings, and artificial sweeteners posing health risks is surprisingly weak given the public uproar. And while I agree that chicken doesn't contain those things, chicken feed typically contains a whole different set of things that would scare people if they had to disclose them, like antibiotics, animal by-products, and lots of artificial ingredients to make up for nutritional deficiencies from a corn/soy-based diet. (Though, to be clear, I think the evidence that those feed additives pose direct health risks is also weak, with the possible exception of antibiotics contributing to antibiotic-resistant Salmonella.)

"the general concept of UPFs is nonsense"

I can't argue with that! In case you're interested, GFI Europe "recently partnered with the Physicians Association for Nutrition to publish one of the most comprehensive, evidence-based guides on plant-based foods and health"* and it makes a very strong case that UPFs are overblown when it comes to concerns over plant based meat since that's usually healthier than conventional meat.

*Source: head of GFI Europe: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/rGt4PADp65iN6zupG/scale-up-the-neglected-bottleneck-facing-alternative?commentId=AGgZmHLmTZ89KYFa8

I directionally agree with this comment, but I think the concept of UPFs is broader / murkier than:

In addition to ingredient-level concerns, people also seem concerned with manufacturing and processing steps like freeze drying, curing, hydrogenating, extremely heating, etc. A commonly-used framework is discussed here. Unfortunately, eliminating "chemical additives" from alternative proteins strikes me as a much easier task than avoiding industrial processing.

(I do think at the consumer level, the working definition of ultra-processed food is probably more vibes-based than either of my links would imply.)

I'm not a nutritionist or an exercise scientist, so I could be interpreting this incorrectly, but I think you are overly dismissive of the idea that people should be eating more protein.

The guideline's recommendation of 0.7 to 1 gram per kilogram daily represents the minimum intake needed to prevent malnutrition and maintain nitrogen balance; it is insufficient for optimal muscle growth when combined with strength training.[1] For people who are trying to increase their muscle mass, Huberman's suggestion is accurate and helpful.[2] Since muscle mass is associated with lower all-cause mortality, I think that Huberman's suggestion (when accompanied with adequate exercise) is more beneficial than the government guideline. This is especially true for older adults, but to ensure healthy aging and longer health spans, it is preferable to build muscle throughout adulthood.

That said, we should, of course, be encouraging people to get as much of their protein intake as possible from non-animal sources. Personally, I encourage vegans to exercise and try to eat in the range of 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound (1.5 to 2.2 grams per kg) of body weight per day, not only for your own health, but to be an example to others that they can reduce animal suffering without sacrificing their health or muscle growth.

Note that the review you linked specifically excludes multi-component interventions, including protein and exercise combinations.

https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/6/376

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8978023/

Note that the first meta-analysis finds that the effect of supplementing protein plateaus at 1.6 g/kg. This is still within Huberman's range, and is still much higher than the guideline of 0.7 - 1. I've seen people in the exercise community quibble a lot about this supposed plateau. My position is that in expectation the benefit of going up from 1.6 g/kg to 2.2 g/kg is higher than the (pretty much non-existent) risk.

This analysis doesn't account for the potential downsides of excess protein consumption -- cf., based on a quick non-AI search, the discussion here for a specific risk, this older review article for a broader discussion.

I don't claim to be qualified to balance those potential tradeoffs against the potential advantages, but think they should be acknowledged.

Hi Jason, thanks for this. I was not aware of this review article. There is a new review article that came out this year, which concludes that there is insufficient evidentiary basis for harm from high protein intake. In particular, it seems like some of the results of previous studies may have been confounded with calorie intake.

Some numbers for emphasis on overconsumption of protein (I'm far from a nutritionist):

A 170 pound man eating 170g protein. Assuming 2400 calories per day that is 28% of calories as protein.

That is more than the recommended quote above

For (potential) vegans that are depressed at the sight of the protein/kcal table. Here's a screenshot of a similar table I put together last year (for myself - UK based). I like sharing this with gym bros that scoff at veganism for lean protein reasons.

Beware that it has a small number of duplicates as I was also tracking prices from different suppliers to compare.

Most of the things on this list have one or two ingredients if that's something you care about.

Here are the top picks sorted by protein per kcal and price (based on Feb 2024 prices).

This is why I make my own seitan.

What a great spreadsheet. It gives me wonderful old-school EA vibes.

Do you have a fav seitan recipe?

I've made seitan 3 times. 1x failure, 1x fairly good, 1x amazing but really time consuming.

Thank you! My base recipe is just:

I make these in bulk and find that the slices freeze well. I find that they work best in curries (Thai and Indian style) and chillies (especially if you cook them in a pressure cooker with all the beans and spices).

I also just snack on them on their own, but that's maybe an acquired taste, like raw tofu or tempeh. (I also sometimes make my own tempeh. It's quite fun! Making tofu turned out to have a really low yield, so I stopped doing that.)

These will turn out quite chewy. Some people don't love that. To make them less dense, I have in the past added baking powder which makes them puff up when boiling - you'll need a big pot for that!

Currently working on seitan sausage recipes, but not happy with any of those yet. If anyone has recommendations, please let me know!

Does this take bioavailability into account? IIUC, humans can't absorb 100% of plant based proteins, while we can absorb nearly 100% of animal-based proteins. The upshot is that your spreadsheet isn't tracking the actual amount of protein human bodies will absorb

Yes, this table does not include data on this. I don’t have columns for values related to that. It’s a lot of work to track these numbers down and for many foods they are just not available.

When people online talk about the “bioavailability” of protein sources, they seem to mean one (or both) of two things:

One is the digestibility. So how much of the amino acids end up absorbed your body. That number is ~90%+ for most soy products (that I have found numbers for) as well as vital wheat gluten.

The other thing that people talk about is the amino acid profile. As one would expect, an animal muscle has the amino acids that one needs to build animal muscle, in about the right relative amounts.

Soy also has all essential amino acids, the profile is just a bit different. But none is particularly low or missing.

Vital wheat gluten is low in lysine. So I wouldn’t recommend relying only on seitan for protein. But if there is a bit of soy or some beans in your diet, I wouldn’t worry about it. (It’s also easy and cheap to supplement but that’s probably usually not necessary.)

Protein quality scores like PDCAAS and DIAAS try to account for both. That's why, on its own, vital wheat gluten ends up with a poor score. But soy products tend to still score highly.

Basically, I am not worried about it and have personally been building muscle without problem on a vegan diet with lots of soy and some seitan. But you are right that accounting for this would probably change the table ordering a little.

sadly, KoRo no longer delivers to the UK

Good post!

I agree that asking people to give up on beef is a very risky move, since it can lead them pretty easily to switch to chicken and salmon which are causing far, far more suffering.

I like your point that many people are not really working out and thus really just need the minimum-ish amount of protein in that case.

I am no longer veg for 2 reasons, in case my 2 cents means anything (tho maybe they are more personal to me than prevalent):

+ Processed food concerns (my specific examples):

-- Daily pea protein intake makes my stomach hurt... not sure if this is definitely related to processing or something else but chicken doesn't do this to me. -- I have trouble getting enough protein from purely unprocessed vegan sources like organic tofu, and organic rice and beans, and peanut butter on wheat bread. I can only eat so much of these 3 things every single day, especially as I lift weights and don't want just the minimum amount of protein. Are there other good unprocessed vegan sources of protein? EAG events and other events don't give me that impression.... lots of pea protein fake meat, and sometimes full set ups with very little protein at all for an entire meal.

-- Products like Soylent that are not organic, have glyphosate, a known carcinogen, and possibly other chemicals. Soylent has readable levels of glyphosate in it, but some think it's too much while others think it's an okay amount. However I'd like to avoid carcinogens in any amount at least when it's easy to.

+ Missing nutrients:

-- Why do so few vegans eat omega-3s from algae oil? Omega-3's from flax etc need to be converted and it seems this doesn't make the cut in what's needed for many people, because it's not the straight up DHA and EPA that the body best uses. "The trouble is that people vary dramatically in their abilities to convert ALA to DHA and EPA. So the only way to ensure that your body receives sufficient amounts of these latter two nutrients is to supplement." Not getting straght up DHA and EPA, impairs long term brain function of at least some vegans. Vegans should supplement with very specifically, algae oil, such as what VivoLife and Dr. Fuhrman sell. (-- Some vegans don't even supplement b12 which is more known). -- I can only wonder if there are additional nutrients that will come to light as time goes on, that vegans seem to be unaware of or careless about in their highlighting of animal suffering.

Telling people to eat less protein, or that they don't need nearly as much protein as they think, seems like a bad idea. I mean, most people do eat far more protein than they need to, but as vegans we are already often considered weak and protein-deficient; we probably don't want to strengthen that stereotype (even though it's plainly ridiculous).

Instinctively, I feel like working to eliminate some of the fear around "processed foods" is probably our best bet. Yes, some vegan protein comes from UPFs but so does plenty of non-vegan protein (like whey protein powder and protein bars) and the protein-obsessed meat-eaters seem to have little issue consuming that - sales of these powders/bars are booming.

Lewis, great article! Some points reminded me of "In Defense of the Certifiers," which I also really enjoyed.

I'm thinking about two other possible approaches to this problem. I haven't fully thought these through, but I thought it might help just to put them out there.

The first has to do with encouraging people to buy from small farmers in their area. My perspective on this might be a little different because, I think unlike most people on this forum, I don't live in a big city. I personally know several farmers in my area, and am acquainted with a few others through seeing and talking with them at the farmers' market, etc. In general, I think their standards for how they treat their animals exceed the standards set by certification organizations -- and sometimes by a lot. Additionally, I think supporting local farming (including vegetable farming) has huge social/community benefits, as well as environmental benefits.

The main counterargument to this approach is probably that local farmers can only supply a small fraction of the demand for animal products. Still, I just wanted to put it out there.

Second, I see a possibility that the demand for meat will decrease as the general public learns more about the role of the microbiome in health. I have been studying the microbiome for the last several months in an attempt to make progress against a supposedly "incurable" immune disorder I've been dealing with... and the results of working on my microbiome have been absolutely wild. I've regained more of my health than was supposed to be possible. Meanwhile, I've learned that (1) diseased microbiome states are associated with so many of the conditions that are on the rise, from cardiovascular disease to anxiety and depression, and (2) a high-meat diet is not healthy from a microbiome perspective. If consciousness of these two points increases over the coming years, could this reduce meat consumption and therefore animal suffering?

I love this post but got to pushback on the recommended protein intake of "0.7 to 1 gram per kilogram daily."

However I agree and/or learned a lot from the rest of this post!

*I asked Chatgpt to factcheck these claims (and it basically endorsed them) and cite sources here: https://chatgpt.com/s/t_690bc48ee7fc819196ef1112f1cefa9f

Thanks David. Yeah I agree that something closer to 1.6 gram per kilogram is probably ideal for gaining muscle mass, per what your ChatGPT answers say. But my guess is that most Americans aren't doing the required weights to actually gain muscle mass. And my guess would be that caloric restriction / GLP-1s are surer ways to loss weight. But I'm also far from an expert on any of this, so on reflection I should have just skipped weighing in on this point at all.

"But I'm also far from an expert on any of this, so on reflection I should have just skipped weighing in on this point at all."

Lol I'm glad you didn't skip it since your writing never fails to brighten my day. And your TED talk was great too btw! Thanks for all your hard work and reading and replying to my comment

Thanks David! That's very kind of you :) And TBC: I wouldn't have skipped the whole newsletter -- just weighing on ideal protein consumption, which was a bit of a digression from the main point. (And I had actually considered just saying something like "I don't know how much protein you should eat, but it doesn't matter because we can't influence it much.")

I’d also guess that eating more protein improves public health in countries where high body weight causes health problems, since protein makes it easier to eat fewer calories.

But the largest increases in animal protein consumption are likely coming from countries that aren’t (yet) facing issues with obesity?

Posts like this remind me how important it is to carefully consider both human health and animal welfare when thinking about the future of protein and how nuanced this is. We need to give space for these convos. I truly appreciated your convo with Dwarkesh.. ty for keeping these essential issues front and center in such a thoughtful and easy to follow way