(This sequence assumes basic familiarity with longtermist cause prioritization concepts, though the issues I raise also apply to non-longtermist interventions.)

Are EA interventions net-positive from an impartial perspective — one that gives moral weight to all consequences, no matter how distant? What if they’re neither positive, nor negative, nor neutral?

Trying to reduce x-risk, improve institutions, or end factory farming might seem robustly positive. After all, we don’t need to be certain in order to do good in expectation. But when we step back to look at how radically far-reaching the impartial perspective is, we start to see a deeper problem than “uncertainty”. This problem is unawareness: many possible consequences of our actions haven’t even occurred to us in much detail, if at all.

Why is unawareness a serious challenge for impartial altruists? Well, impartiality entails that we account for all moral patients, and all the most significant impacts we could have on them. Here’s a glimpse of what such an accounting might require:

How likely is it that we’re missing insights as “big if true” as the discovery of other galaxies, the possibility of digital sentience, or the grabby aliens hypothesis? What’s the expected value of preventing extinction, given these insights? Or set aside long-term predictions for now. What are all the plausible pathways by which we might prevent or cause extinction by, say, designing policies for an intelligence explosion? Not just the pathways we find most salient.

It’s no secret that the space of possible futures is daunting. But whenever we make decisions based on the impartial good, we’re making tradeoffs between these futures. Imagine what it would take to grasp such tradeoffs. Imagine an agent who could conceive of a representative sample of these futures, in fairly precise detail. This agent might still be highly uncertain which future will play out. They might even be cognitively bounded. And yet, if they claimed, “I choose to do instead of because has better expected consequences”, they’d have actually factored in the most important consequences. All the heavy weights would be on the scales.

And then there’s us. We don’t merely share this agent’s limitations. Rather, we are also unaware (or at best only coarsely aware) of many possible outcomes that could dominate our net impact. How, then, can we weigh up these possibilities when making choices from an impartial perspective? We have some rough intuitions about the consequences we’re unaware of, sure. But if those intuitions are so weakly grounded that we can’t even say whether they’re “better than chance” on net, any choices that rely on them might be deeply arbitrary. So whether we explicitly try to maximize EV, or instead follow heuristics or the like, we face the same structural problem. For us, it’s not clear what “better expected consequences” even means.

Of course, we don’t always need to be aware of every possible outcome to make justified decisions. With local goals in familiar domains (picking a gift for your old friend, treating your headache), our choices don’t seem to hinge on factors we’re unaware of. The goal of improving overall welfare across the cosmos, alas, isn’t so forgiving. For example, if you weren’t aware of the alignment problem, you might favor accelerating the development of artificial superintelligence (ASI) to prevent other x-risks! And when we try to concretely map out our impacts on the far future, or even on unprecedented near-term events like ASI takeoff, we find that sensitivity to unawareness isn’t the exception, but the rule.

This isn’t to say our unknown impacts are net-negative. But can we reasonably assume they cancel out in expectation? If not, we’ll need some way to make impartial tradeoffs between outcomes we’re unaware of, despite the ambiguity of those tradeoffs.

In response, the EA community has advocated supposedly “robust” strategies:[1] favoring broad interventions, trusting simple arguments, trying to prevent bad lock-in, doing research, saving for future opportunities… Yet it’s not clear why exactly we should consider these strategies “robust” to unawareness. Perhaps it’s simply indeterminate whether any act has better expected consequences than the alternatives. If so, impartial altruism would lose action-guiding force — not because of an exact balance among all strategies, but because of widespread indeterminacy.

In this sequence, I’ll argue that from an impartial perspective, unawareness undermines our justification for claiming any given strategy is better than another (including inaction). The core argument is simple: (i) Under some plausible ways of precisely evaluating strategies’ consequences, strategy is better than ; (ii) under others, is worse; and (iii) it’s arbitrary which precise values we use.[2] But we’ll take things slowly, to properly engage with various objections:

- The problem (this post): When we choose actions under unawareness, the tradeoffs between these actions’ possible outcomes are underspecified. So, for us, the precise EV framework is unmotivated.

- Why “best guesses” don’t solve it: Our intuitions don’t seem to account for unawareness precisely enough to let us say which strategies have net-better consequences, without more explicitly modeling these consequences.

- Why it undermines action guidance: Under unawareness, the difference between two strategies’ “EV” should be severely imprecise, i.e., a wide interval rather than one number. This imprecision isn’t just low confidence, but fundamental indeterminacy — we don't have reason to narrow the interval further. Since this interval will almost always span both positive and negative values,[3] it’s indeterminate which strategy is better.

- Why existing solutions don’t work: None of the candidate EA approaches to comparing strategies’ impact, including wager arguments, resolve this indeterminacy.

Yes, we ultimately have to choose something. Inaction is still a choice. But if my arguments hold up, our reason to work on EA causes is undermined. Concern for the impartial good would give us no more reason to work on these causes than to, say, prioritize our loved ones.

It’s tempting to ignore unawareness because of these counterintuitive implications. Surely “trying to stop AI from killing everyone is good” is more robust than some elaborate epistemic argument? Again, though, impartial altruism is a radical ethical stance. We’re aiming to give moral weight to consequences far more distant in space and time than our intuitions could reasonably track. Arguably, ASI takeoff will be so wildly unfamiliar that even in the near term, we can’t trust that trying to stop catastrophe will help more than harm. Is it so surprising that an unusual moral view, in an unusual situation, would give unusual verdicts?

I’m as sympathetic to impartial altruism as they come. It would be arbitrary to draw some line between the moral patients who “count” and those who don’t, at least as far as we’re trying to make the world a better place. But I think the way forward is not to deny our epistemic situation, but to reflect on it, and turn to other sources of moral guidance if necessary. Just because impartial altruism might remain silent, that need not mean your conscience does.

Sequence summary

I’ll include each of the list items below as a “Key takeaway” at the start of the corresponding section of the sequence.

- This post:

- Unawareness consists of two problems: The possible outcomes we can conceive of are too coarse to precisely evaluate, and there are some outcomes we don’t conceive of in the first place. (more)

- Thus, unlike standard uncertainty, under unawareness it’s unclear how to make tradeoffs between the possible outcomes we consider when making decisions. (more)

- We can’t dissolve this problem by avoiding explicit models of the future, or by only asking what works empirically. (more)

- A vignette illustrates how unawareness might undermine even intuitively robust interventions, like trying to reduce AI x-risk. (more)

- Why intuitive comparisons of large-scale impact are unjustified:

- The generalization of “expected value” to the case of unawareness should be imprecise, i.e., not a single number, but an interval. This is because assigning precise values to outcomes we’re not precisely aware of would be arbitrary. This imprecision doesn’t represent uncertainty about some “true EV” we’d endorse with more thought. Rather, it reflects irreducible indeterminacy: there is no single value pinned down by our evidence and epistemic principles. (more)

- Suppose we have (A) a deep understanding of the mechanisms determining a strategy’s consequences on some scale, and (B) evidence of consistent success in similar contexts. Then, we can trust that our intuitions factor in unawareness precisely enough to justify comparing strategies, relative to that scale. (more)

- Unlike in everyday decision situations, we have neither (A) nor (B) when making choices based on the impartial good:

- Our understanding of our effects on high-stakes outcomes seems too shallow for us to have precisely calibrated intuitions. This is due to the novel and empirically inaccessible dynamics of, e.g., the development of superintelligence, civilization after space colonization, and possible interactions with other universes. (more)

- The mechanisms we’re unaware of might be qualitatively distinct from those we’re aware of. They’re not merely the minor variations we know superforecasters can handle. (more)

- Instead of consistent success, we have a history of consistently fragile models of how to promote the impartial good. Based on EAs’ track record of discovering sign-flipping considerations and new scales of impact, we’re likely unaware of more such discoveries. (more)

- If we don’t know how to weigh up evidence about our overall impact that points in different directions, then an intuitive precise guess is not a tiebreaker. This intuition is just one more piece of evidence to weigh up. (more)

- Why impartial altruists should suspend judgment under unawareness:

- To get the imprecise “EV” of a strategy under unawareness, we take the EV with respect to all plausible ways of precisely evaluating coarse outcomes. Given two strategies, if neither strategy is net-better than the other under all these ways of making precise evaluations, then we’re not justified in comparing these strategies. (more; more)

- Our evaluations of pairs of strategies should be so severely imprecise that they’re incomparable, absent arguments to the contrary. This is for two reasons:

- Given the possibilities we’re aware of, there are very few constraints on how to precisely model the possibilities we’re unaware of. This lack of constraints is worsened by systematic biases in how we discover new hypotheses. For example, we may be disproportionately likely to consider hypotheses that we happen to find interesting. (more)

- Suppose we try breaking down the space of possible outcomes into manageable categories. Since we can only break things down so far, the categories we can model remain too coarse-grained to pin down whether a strategy’s expected upsides outweigh its downsides. (more)

- We have unawareness at the level of both (i) how good different world-states are (like “misaligned AIs take over”) relative to each other, and (ii) how effective concrete interventions are at steering toward vs. away from a given world-state. (more)

- When we model the impact of the AI safety intervention from the vignette in (1d), the structural problems from (3b) and (3c) undermine the case for that intervention. That is, given reasonable ranges of parameter estimates, the intervention is positive under some estimates and negative under others, and it’s arbitrary how we weigh up their plausibility. (more)

- Why existing approaches to cause prioritization are not robust to unawareness:

- We can’t assume the considerations we’re unaware of “cancel out”, because when we discover a new consideration, this assumption no longer holds. (more)

- We can’t trust that the hypotheses we’re aware of are a representative sample (see 3.b.i), so we can’t naïvely extrapolate from them. Although we don’t know the net direction of our biases, this doesn’t justify the very strong assumption that we’re precisely unbiased in expectation. (more)

- Similarly, we can’t trust that a strategy’s past success under smaller-scale unawareness is representative of how well it would promote the impartial good. The mechanisms that made a strategy work historically could actively mislead us when predicting its success on a deeply unfamiliar scale. (more)

- The argument that heuristics are robust assumes we can neglect complex effects (i.e., effects beyond the “first order”), either in expectation or absolutely. But under unawareness, we have no reason to think these effects cancel out, and should expect them to matter a lot collectively. (more)

- Even if we focus on near-term lock-in, we can’t control our impact on these lock-in events precisely enough, nor can we tease apart their relative value when we only picture them coarsely. The “punt to the future” approach doesn’t help for similar reasons. (more; more)

- Suppose that when we choose between strategies, we only consider the effects we can weigh up under unawareness, because (we think) the other effects aren’t decision-relevant. Then, it seems arbitrary how we group together “effects we can weigh up”. (more)

- Taking stock, the appropriate next step is not to wager on the possibility that unawareness is manageable. Instead, we should acknowledge the limits of action guidance from impartial altruism, rethink the foundations of our prioritization, and consider other ethical perspectives. (more)

Bird’s-eye view of the sequence

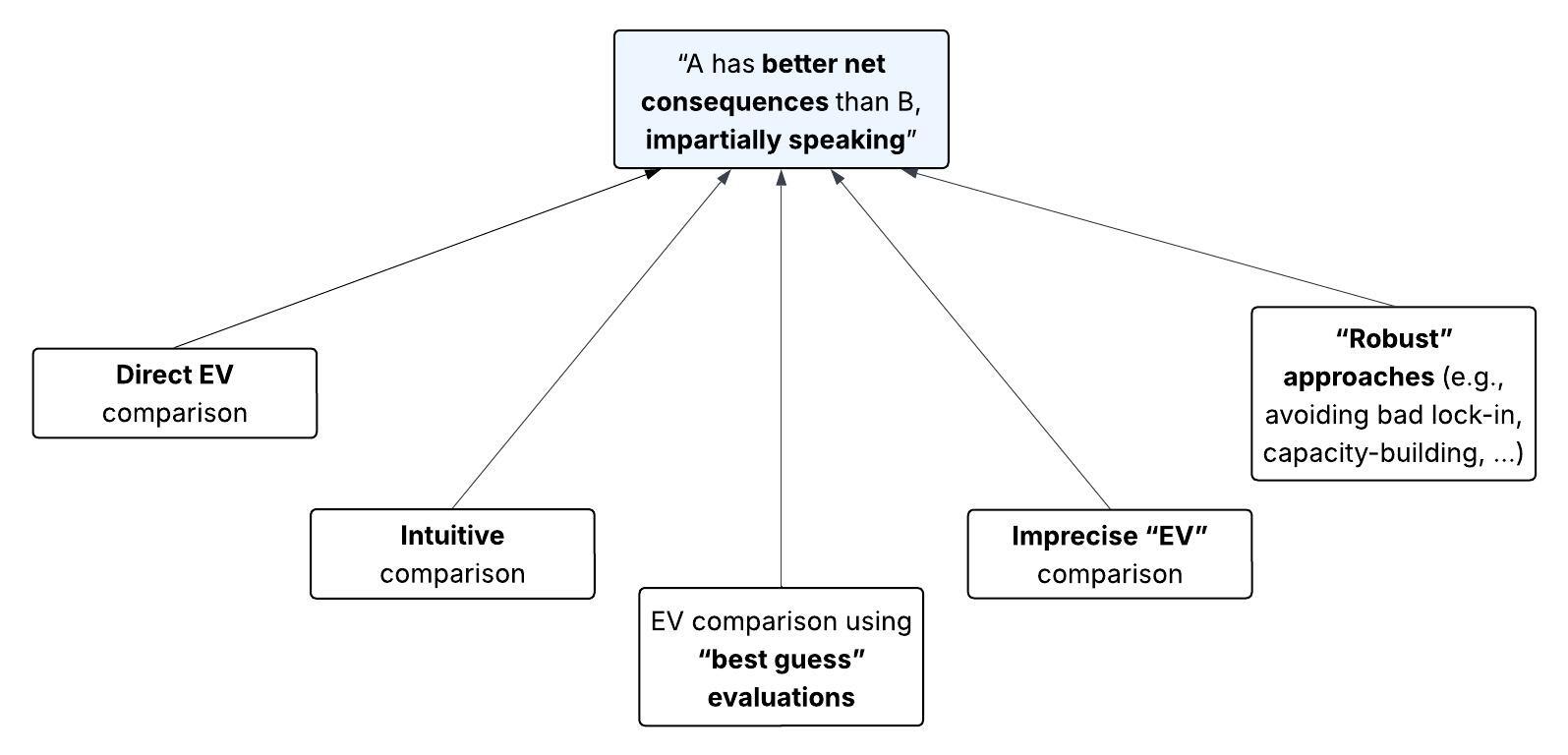

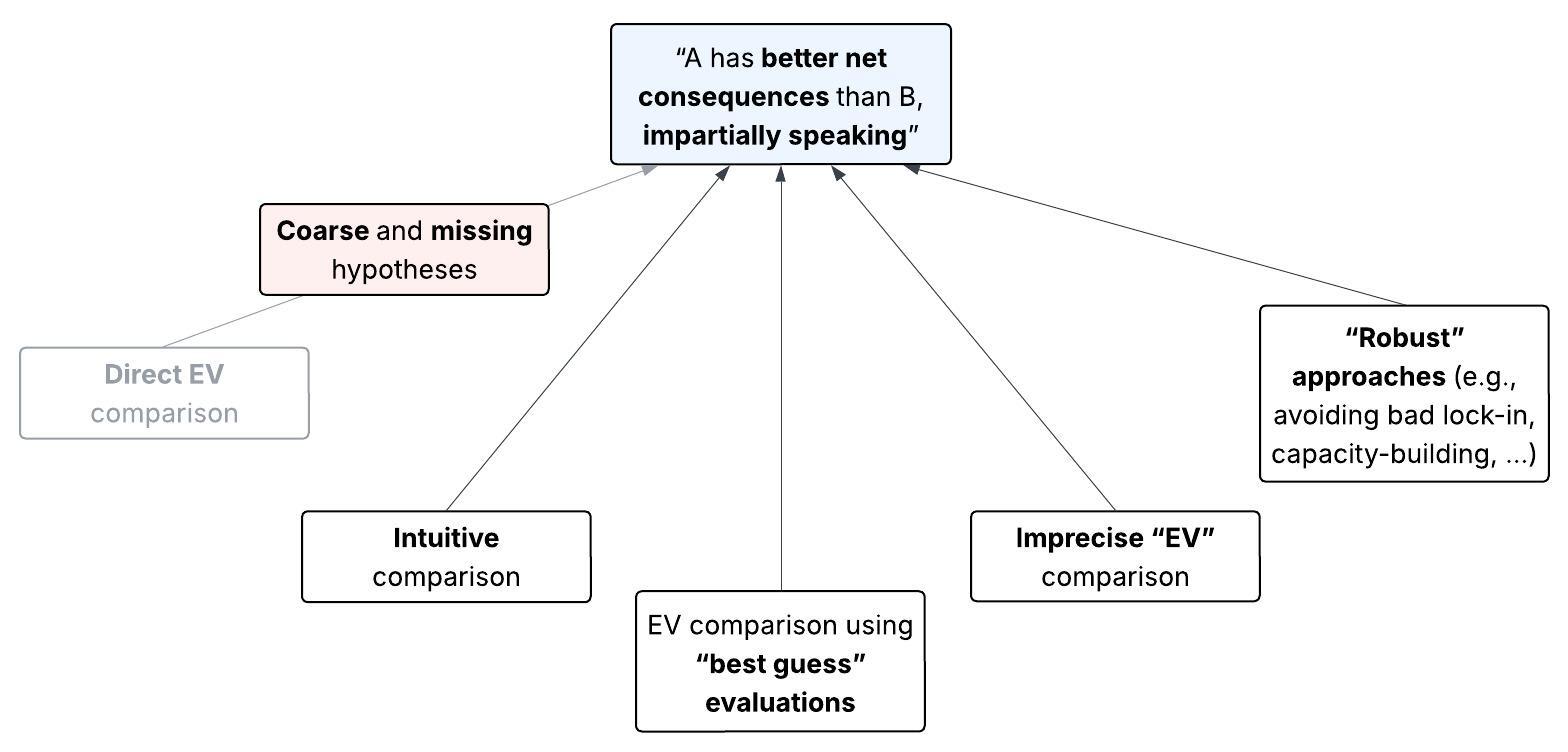

Our question is, what could justify the kind of claim in the blue box below? We’ll walk through what seem to be all the live options (white boxes), and see why unawareness pulls the rug out from under each one. (Don’t worry if you aren’t sure what all these options mean.)

|

Introduction to unawareness

Key takeaway

Unawareness consists of two problems: The possible outcomes we can conceive of are too coarse to precisely evaluate, and there are some outcomes we don’t conceive of in the first place.

What exactly is our epistemic predicament? And why is it incompatible with the standard framework for evaluating interventions, that is, expected value?

The challenge: As impartial altruists, we care about the balance of value over the whole future. But, for any future trajectory that might result from our actions, we either (1) don’t have anything close to a precise picture of that balance, or (2) don’t foresee the trajectory at all.

In broad strokes, we’ve acknowledged this challenge before. We know we might be missing crucial considerations, that we’d likely be way off-base if we were EAs in the 1800s, and so on. For the most part, however, we’ve only treated these facts as reasons for more epistemic humility. We haven’t asked, “Wait, how can we make tradeoffs between possible outcomes of our actions, if we can barely grasp those outcomes?” Let’s look more closely at that.

We’d like to choose between some strategies, based on impartial altruist values. We represent “impartial altruism” with a value function that gives nontrivial moral weight to distant consequences (among other things). Since we’re uncertain which possible world will result given our strategy, we consider the set of all such worlds. For any world in that set, our value function returns a number representing how good this world is. (If any of this raises an eyebrow, see footnote.[4])

If we were aware of all possible worlds, we could conceive of every feature relevant to their value (say, the welfare of every sentient being). Then we could make judgments like, “Weighing up all possible outcomes, donating to GiveDirectly seems to increase expected total welfare.” That’s a high bar, and I don’t claim we need to meet it. But whatever justification we give for decision-making based on , we’ll need to reckon with two ways our situation is structurally messier:[5]

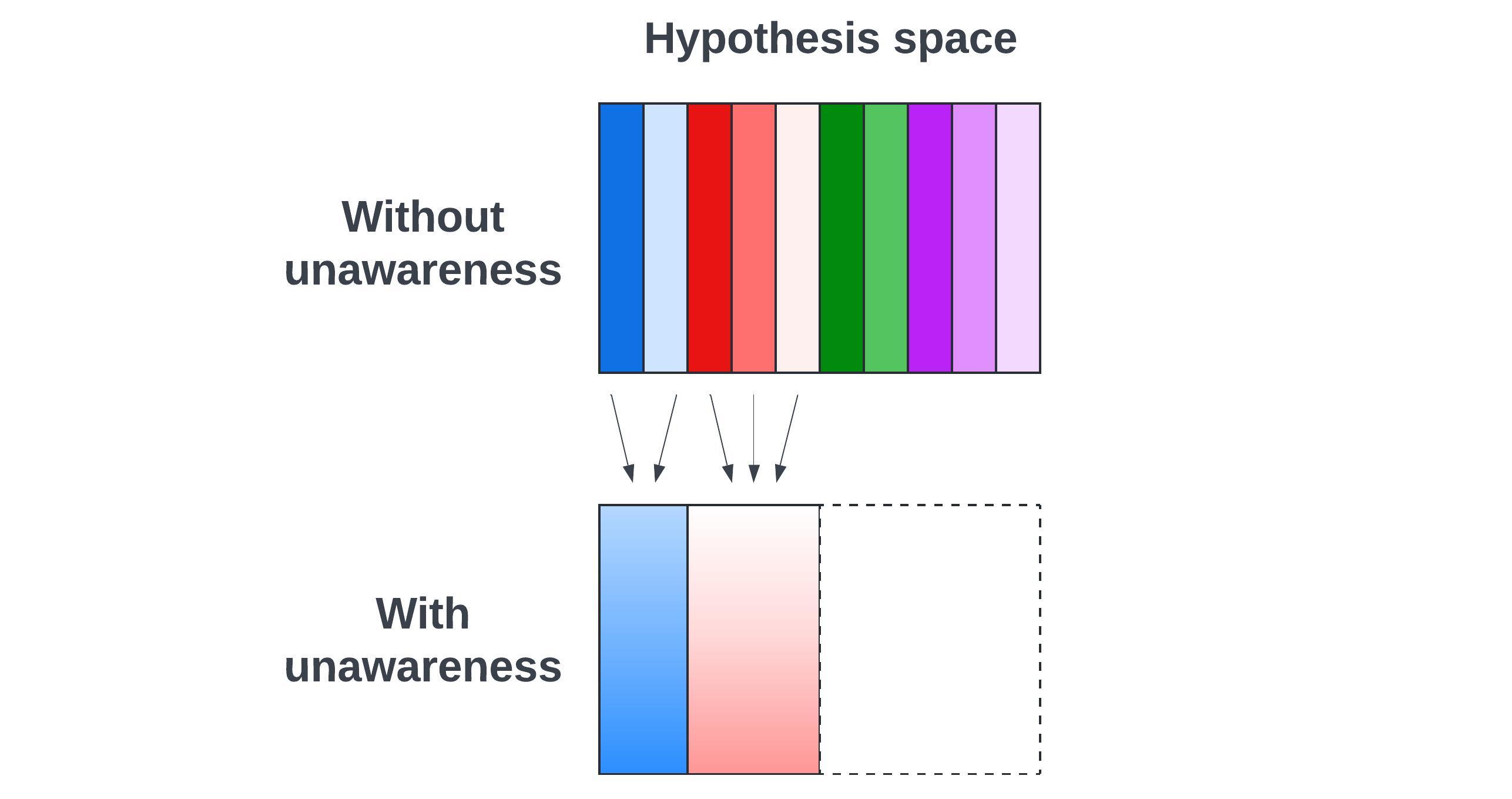

- We can’t conceive of possible worlds in full detail. Instead, we’re only coarsely aware of them in the form of hypotheses, which are sets of possible worlds described abstractly. In practice, these descriptions don’t come close to specifying every morally relevant aspect of the futures they cover. They’re more like “misaligned ASI takes over” or “future people care about wild animals”. So, a single hypothesis might gloss over large differences in value across the possible worlds it contains.

For some possible worlds, we are unaware of any hypotheses that contain them. That is, these hypotheses haven’t occurred to us in enough detail to factor into our decision-making. For example, we’re unaware of the sets of worlds where undiscovered crucial considerations are true. (You might wonder if we could get around this problem with more clever modeling; see footnote.[6])

|

| Figure 1. The hypotheses the fully aware agent conceives of are fine-grained possible worlds (thin rectangles). And this agent is aware of all such worlds. An unaware agent conceives of coarse-grained hypotheses that lump together multiple possible worlds (thick rectangles), and these hypotheses don’t cover the full space of worlds (dotted rectangle). |

Fig. 1 illustrates both problems, which I’ll collectively call “unawareness”. Post #2 will explore these epistemic gaps much more concretely, from big-picture considerations to more mundane causal pathways. For now, what matters is how we differ in general from fully aware agents.

Unawareness vs. uncertainty

Key takeaway

Unlike standard uncertainty, under unawareness it’s unclear how to make tradeoffs between the possible outcomes we consider when making decisions.

These two problems might seem like mere flavors of regular old uncertainty. Why can’t we handle unawareness by just taking the expected value (perhaps with a Bayesian prior that bakes in common sense)? As Greaves and MacAskill (2021, Sec. 7.2) say:

Of course, failure to consider key fine-grainings might lead to different expected values and hence to different decisions, but this seems precisely analogous to the fact that failure to possess more information about which state in fact obtains similarly affects expected values (and hence decisions).

To respond to this, let’s revisit why we care about EV in the first place. A common answer: “Coherence theorems! If you can’t be modeled as maximizing EU, you’re shooting yourself in the foot.” For our purposes, the biggest problem with this answer is: Suppose we act as if we maximize the expectation of some utility function. This doesn’t imply we make our decisions by following the procedure “use our impartial altruistic value function to (somehow) assign a number to each hypothesis, and maximize the expectation”.[7]

So why, and when, is that particular procedure appealing? When you’re aware of every possible world relevant to your value function, then even if you’re uncertain, it’s at least clear how to evaluate each world. In turn, it’s clear how the worlds trade off against each other, e.g., “ saves 2 more lives than in world ; but saves 1 more life than in world , which is 3 times as likely; so has better consequences”. Your knowledge of these tradeoffs justifies the use of EV to represent how systematically good your action’s consequences are.[8]

Whereas, if you’re unaware or only coarsely aware of some possible worlds, how do you tell what tradeoffs you’re making? It would be misleading to say we’re simply “uncertain” over the possible worlds contained in a given hypothesis, because we haven’t spelled out the range of worlds we’re uncertain over in the first place. The usual conception of EV is ill-defined under unawareness.

Now, we could assign precise values to each hypothesis , by taking some “best guess” of the value averaged over the possible worlds in . Then we’d get a precise EV, indirectly. We’ll look more closely at why that’s unjustified next time. The problem for now is that this approach requires additional epistemic commitments, which we’d need to positively argue for. Since we lack access to possible worlds, our precise guesses don’t directly come from our value function , but from some extra model of the hypotheses we’re aware of (and unaware of).

Worse yet, unawareness appears especially troubling for impartial altruists. We care about what happens to every moral patient over the whole future. A highly abstract description of a future trajectory doesn’t capture that. So we have two challenges:

- We need to somehow evaluate very coarse-grained descriptions of worlds (i.e., hypotheses), without pretending that is well-defined on them. Take the hypothesis “misaligned ASI takes over”. While we have some rough idea how bad that would be, the value could vary a lot across the specific scenarios this hypothesis describes, e.g., some misaligned ASIs could be more spiteful than others. These aren’t minor nitpicks.

- We need to avoid arbitrarily ignoring hypotheses relevant to a strategy’s overall impact, when we’re unaware of them. The standard fix is to add a catch-all hypothesis, “everything I didn’t think of”, which contains all the possible worlds not contained in any hypotheses we’re aware of. But “everything I didn’t think of” is, to put it mildly, pretty abstract. The catch-all seems to tell us basically nothing about how well different strategies will do. (Can we conclude from this that the catch-all “cancels out”?)

Currently, I’m merely pointing out the prima facie problem. The third post will look at how serious the problems of coarseness and the murkiness of the catch-all are (spoiler: very).

|

Why not just do what works?

Key takeaway

We can’t dissolve this problem by avoiding explicit models of the future, or by only asking what works empirically.

Before moving on, an important note: unawareness specifically challenges the justification or reasons for our decisions. This isn’t a purely empirical problem, nor one that can be dissolved by avoiding explicit models of our impact. In particular, we might think something like:

We already knew that naïve EV maximization doesn’t work, and humans can’t be ideal Bayesians. That’s why we should stop trying to derive our decisions from a foundational Theory of Everything, grounded purely in explicit world models. Instead, we should do what seems to work for bounded agents. This often entails following heuristics, common sense intuitions, or model-free “outside views”, refined over time by experience (see, e.g., Karnofsky).

“Winning isn’t enough”, by Jesse Clifton and myself, argues that this response is inadequate. Here’s the TL;DR. (Feel free to skip this if you’re familiar with that post.)

If we want to tell which strategies have net-positive consequences, we can’t avoid the question of what it means to have “net-positive consequences”. Answering this question doesn’t require us to solve all of epistemology and decision theory. Nor do we need a detailed formal model tallying up our chosen strategy’s consequences. Our justifications will often be vague and incomplete, and our models will often be high-level. E.g., “the mechanisms that make this procedure work in these domains seem very similar to the mechanisms in others”, or “I have reasons XYZ to trust that my intuition tracks the biggest consequences”.

But these justifications must bottom out in some all-things-considered model of how a strategy leads to better consequences, including those we’re unaware of. This is as true for intuitive judgments, heuristics, or supposedly model-free extrapolations, as anything else. (Whether those methods resolve unawareness remains to be seen. I’ll argue in the second and final posts that they don’t.)

Case study: Severe unawareness in AI safety

Key takeaway

This vignette illustrates how unawareness might undermine even intuitively robust interventions, like trying to reduce AI x-risk.

On a fairly abstract level, we’ve seen that we can’t reduce unawareness to ordinary uncertainty. Now let’s ground things more concretely with a simple story.[9]

Vignette

I want to increase total welfare across the cosmos. Seems pretty daunting! Nonetheless, per the standard longtermist analysis, I reason, “The value of the future hinges on a few simple levers that could get locked in within our lifetimes, like ‘Is ASI aligned with human values?’ And it doesn’t seem that hard to nudge near-term levers in the right direction. So it seems like x-risk reduction interventions will be robust to missing details in our world-models.”

Inspired by this logic, I set out to choose a cause area. Trying to stop AIs from permanently disempowering humans? Looks positive-EV to me. Still, I slow down to check this. “What are the consequences of that strategy,” I wonder, “relative to just living a normal life, not working on AI risk?”

Well, let’s say I succeed at preventing human disempowerment by AI, with no bad off-target effects of similar magnitude. That looks pretty good! At least, assuming human space colonization (“SC”) is better than SC by human-disempowering AIs. Clearly(?), SC by humans with my values would be better by my lights than SC by human-disempowering AIs.

But then I begin to wonder about other humans’ values. There’s a wide space of possible human and AI value system pairs to compare. And some human motivations are pretty scary, especially compared to what I imagine Claude 5.8 or OpenAI o6 would be like. Also, it’s not only the initial values that matter. Maybe humans would differ a lot from AIs in how much (and what kind of) reflection they do before value lock-in, or how they approach philosophy, or how cooperative they are.[10] Is our species unusually philosophically stubborn? My guess is that this stuff cancels out, but this feels kinda arbitrary. I feel like I need a much more fine-grained picture of the possibilities, to say which direction this all pushes in.

Also, if I try to stop human disempowerment by, say, working on AI control, how does this effort actually affect the risk of disempowerment? The intended effects of AI control sure seem good. And maybe there are flow-through benefits, like inspiring others to work on AI safety too. But have I precisely accounted for the most significant ways that this research could accelerate capabilities, or AI companies that implement control measures could get complacent about misalignment, or the others I inspire to switch to control would’ve more effectively reduced AI risk some other way, or …?[11] Even if I reduce disempowerment risk, how do I weigh this against the possible effects on the likelihood of catastrophes that prevent SC entirely? For all I know, my biggest impact is on AI race dynamics that lead to a war involving novel WMDs. And if no one from Earth colonizes space, how much better or worse might SC by alien civilizations be?

Hold on, this was all assuming I can only influence my lightcone. Acausal interactions are so high-stakes that I guess they dominate the calculus? I don’t really know how I’d begin tallying up my externalities on the preferences of agents whose decision-making is correlated with mine (Oesterheld 2017), effects on the possible weird path-dependencies in “commitment races”, or the like. After piecing together what little scraps of evidence and robust arguments I’ve got, my guesses beyond that are pulled out of a hat, if I’m being honest. Maybe there are totally different forms of acausal trade we haven’t thought of yet? Or maybe the acausal stuff all depends a lot on really philosophically subtle aspects of decision theory or anthropics I’m fundamentally confused about? Or, if I’m in a simulation, I have pretty much no clue what’s going on.

Where this leaves us

We’ve looked at the most apparently robust, battle-tested class of interventions available to an impartial altruist. Even here, unawareness looms quite large. In the end, we could say, “Let’s shrink the EV towards zero, slap on some huge error bars, and carry on with our ‘best guess’ that it’s positive.” But is that our actual epistemic state?

This vignette alone doesn’t show we have no reason to work on AI risk reduction. What it does illustrate is that if we assign a precise EV to an intervention under unawareness, the sign of the EV seems sensitive to highly arbitrary choices.[12] That’s a problem we must grapple with somehow, even if we ultimately reject this sequence’s strongest conclusions.

Even so, we might think these choices aren’t actually arbitrary, but instead grounded in reliable intuitions. (At least, maybe for some interventions, and the problems above are just quirks of AI risk?) Rejecting such intuitions may seem like a fast track to radical skepticism. In the next post I’ll argue that, on the contrary: Yes, our intuitions can provide some guidance, all else equal. But all else is not equal. When our goal is to improve the future impartially speaking, the guidance from our intuitions isn’t sufficiently precise to justify judgments about an intervention’s sign — but this isn’t true for more local, everyday goals.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Nicolas Macé, Sylvester Kollin, Jesse Clifton, Jim Buhler, Clare Harris, Michael St. Jules, Guillaume Corlouer, Miranda Zhang, Eric Chen, Martín Soto, Alex Kastner, Oscar Delaney, Capucine Griot, and Violet Hour for helpful feedback and suggestions. I edited this sequence with assistance from ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini. Several ideas and framings throughout this sequence were originally due to Anni Leskelä and Jesse Clifton. This does not imply their endorsement of all my claims.

References

Bradley, Richard. 2017. Decision Theory with a Human Face. Cambridge University Press.

Canson, Chloé de. 2024. “The Nature of Awareness Growth.” Philosophical Review 133 (1): 1–32.

Easwaran, Kenny. 2014. “Decision Theory without Representation Theorems.” Philosophers’ Imprint 14 (August). https://philpapers.org/rec/EASDTW.

Greaves, Hilary. 2016. “Cluelessness.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 116 (3): 311–39.

Greaves, Hilary, and William MacAskill. 2021. “The Case for Strong Longtermism.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 5-2021, University of Oxford.

Hájek, Alan. 2008. “Arguments for–or against–Probabilism?” British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 59 (4):793-819.

Meacham, Christopher J. G., and Jonathan Weisberg. 2011. “Representation Theorems and the Foundations of Decision Theory.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 89 (4): 641–63.

Mogensen, Andreas L. 2020. “Maximal Cluelessness.” The Philosophical Quarterly 71 (1): 141–62.

Oesterheld, Caspar. 2017. “Multiverse-Wide Cooperation via Correlated Decision Making.” https://longtermrisk.org/files/Multiverse-wide-Cooperation-via-Correlated-Decision-Making.pdf.

Paul, L.A., and John Quiggin. 2018. “Real world problems.” Episteme. 2018;15(3):363-382. doi:10.1017/epi.2018.28

Roussos, Joe. 2021. “Unawareness for Longtermists.” 7th Oxford Workshop on Global Priorities Research. June 24, 2021. https://joeroussos.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/210624-Roussos-GPI-Unawareness-and-longtermism.pdf.

Steele, Katie, and H. Orri Stefánsson. 2021. Beyond Uncertainty: Reasoning with Unknown Possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

- ^

See, respectively, (e.g.) Tomasik (broad interventions); Christiano and Karnofsky (simple arguments); and Greaves and MacAskill (2021, Sec. 4) (lock-in, research, and saving).

- ^

This problem is related to, but distinct from, “complex cluelessness” as framed in Greaves (2016) and Mogensen (2020). Mogensen argues that our credences about far-future events should be so imprecise that it’s indeterminate whether, e.g., donating to AMF is net-good. I find his argument compelling (and some of my arguments in the final post bolster it). However, to my knowledge, no existing case for cluelessness has acknowledged unawareness as a distinct epistemic challenge, except the brief treatment in Roussos (2021).

- ^

E.g., .

- ^

Remarks:

- “Nontrivial moral weight to distant consequences” is deliberately vague. I mean to include not only unbounded total utilitarianism, but also various bounded-yet-scope-sensitive value functions (see Karnofsky, section “Holden vs. hardcore utilitarianism”, and Ngo). I also bracket infinite ethics shenanigans.

- Here, a “possible world” is a possible way the entire cosmos could be, not the kind of “possible world” referred to in the mathematical universe hypothesis (which says that all mathematically possible worlds exist). Strictly speaking, we don’t need to know everything about a possible world to precisely evaluate it by impartial altruist lights, but nothing about my argument hinges on this point.

- ^

These two problems correspond to “coarse awareness” and “restricted awareness”, respectively, from Paul and Quiggin (2018, Sec. 4.1). For other formal models of unawareness, see, e.g., Bradley (2017, Sec. 12.3), Steele and Stefánsson (2021), and de Canson (2024).

- ^

Remarks:

- “In enough detail” is key. Suppose you tried to, say, implicitly specify all physically possible worlds via a set of initial conditions and dynamical laws. You still wouldn’t conceive of what these worlds are like concretely, thus you wouldn’t know how to evaluate them.

- Technically, we could dissolve problem (2) by partitioning the set of possible worlds into, say, “misaligned ASI takes over” and “misaligned ASI doesn’t take over”. However, as we’ll see in the third post, when we evaluate these hypotheses, we’ll do so by considering a range of more concrete sub-hypotheses that we could assign more precise values to (like “misaligned ASI takes over and tiles the lightcone with paperclips”, etc.). Then, in practice, we’ll still leave out relevant possibilities at some level. Thus it will be helpful to model ourselves as unaware of some hypotheses.

- ^

For more, see Meacham and Weisberg (2014, Sec. 4), Hájek (2008, Sec. 3), and this post.

- ^

Cf. the arguments for EV maximization in Easwaran (2014) and Sec. III of Carlsmith.

- ^

- ^

Example of restricted awareness: What if we’re completely missing some way a space-colonizing civilization’s philosophical attitudes affect how much value it produces?

- ^

Example of coarse awareness: How do we weigh up the likelihoods of these fuzzily sketched pathways from the intervention to an AI takeover event?

- ^

You might think, “My values are ultimately arbitrary in a sense. I have the values I have because of flukes of my biology, culture, etc.” This is not what I mean by “arbitrary”. A choice is “arbitrary” to the extent that it’s made for no (defensible) reason. Insofar as you make decisions based on impartial altruistic values, those values alone don’t tell you how to evaluate a given hypothesis, as we’ve seen. I’ll say a bit more on how I’m thinking about arbitrariness next time.

Hi Anthony. Do you think the expected welfare of 2 states of the world which only differ infinitesimally can be incomparable? I do not see how this could be possible. For example, it feels super counterintuitive to me that, given 2 identical states, moving an electron by 10^-100 m in one of the states would make their expected welfare incomparable. I guess one can get from any state of the universe to another in an astronomical number of infinitesimal steps, and I believe any 2 states which only differ infinitesimally are comparable. So I conclude any 2 states are comparable too, even if it is very hard to compare them, to the point that I do not know if electrically stunning shrimps increases welfare in expectation.

This is great - I'm looking forward to reading the rest.

I often avoid thinking in this direction because it feels dangerous to expose yourself to a possibly unbounded scepticism about impact. But it's not authentic to avoid the question of unawareness. Thanks for nudging me to think about this again!

PS- unless this is answered in later posts in the sequence - what's the relationship between 'unawareness' and 'complex cluelessness' and 'crucial considerations'? They seem to be pointing at the same concept (we don't know for sure that we are aware of the biggest effect our actions will have/ the most relevant value to the actions we are taking).

Thanks Toby, I'm glad you find this valuable. :)

On how this differs from complex cluelessness, copying a comment from LW:

I think of crucial considerations as one important class of things we may be unaware of. But we can also be unaware/coarsely aware of possible causal pathways unfolding from our actions, even conditional on us having figured out all the CCs per se. These pathways could collectively dominate our impact. (That's what I was gesturing at with the ending of the block-"quote" in the sequence introduction.)

Meta: I'm interested to hear if any readers would find either of the following accompanying resources below (not yet written up) useful. Please agree-vote accordingly, perhaps after an initial skim of the sequence. :)

I haven't yet read the sequence, but I have it on my backlog to read based on finding your older post about this very interesting. I agree-voted "An FAQ about various objections" because I think the other two can be looked up/skimmed from the existing content, whereas I'm actually unfamiliar with the objections so that would be new info to me.

I don't have time to read the full post and series but the logic of your argument reminds me very much of Werner Ulrich's work. May be interesting for you to check him out. I will list suggested references in order of estimated cost/benefit. The first paper is pretty short but already makes some of your key arguments and offers a proposal for how to deal with what you call "unawareness".

Ulrich, W. (1994). Can We Secure Future-Responsive Management Through Systems Thinking and Design? Interfaces, 24(4), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.24.4.26

Ulrich, W. (2006). Critical Pragmatism: A New Approach to Professional and Business Ethics. In Interdisciplinary Yearbook for Business Ethics. V. 1, v. 1,. Peter Lang Pub Inc.

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical heuristics of social planning: A new approach to practical philosophy. P. Haupt.

Thanks for the post, Anthony.

There is an astronomical number of precise outcomes of rolling a die. For example, the die may stop in an astronomical number of precise locations. So there is a sense in which I am "unaware or only coarsely aware" of not only "some possible worlds", but practically all possible worlds. However, I can still precisely estimate the probability of outcomes of rolling a die. Predictions about impartial welfare will be much less accurate, but still informative, at least negligibly so, as long as they are infinitesimaly better than chance. Do you agree?

If not, do you have any views on which of the following I should do tomorrow to increase expected total hedonistic welfare (across all space and time)?

It is obvious for me the 2nd option is much better.

Hi Vasco — your die roll example is helpful for illustrating my point, thanks!

When you're predicting the "outcome" of a die roll in the typical sense, all you care about is the number of pips on the upward-facing side of the die. So all the physical variations between the trajectories of the die rolls don't matter at this level of abstraction. You don't have coarse awareness here relative to the class of outcomes you care about.

By contrast (as I note in this section), impartial altruists intrinsically care about an extremely detailed set of information: how much welfare is instantiated across all of space and time. With respect to that class of value systems, we do have (severely) coarse awareness of the relevant outcomes. You might think we can precisely estimate the value of these coarse outcomes "better than chance" in some sense (more on this below), but at the part of the post you're replying to, I'm just making this more fundamental point: "Since we lack access to possible worlds, our precise guesses don’t directly come from our value function v, but from some extra model of the hypotheses we’re aware of (and unaware of)." Do you agree with that claim?

I recommend checking out the second post, especially these two sections, for why I don't think this is valid.

That post also spells out my response to your claim "It is obvious for me the 2nd option is much better." I don't think anything is "obvious" when making judgments about overall welfare across the cosmos. (ETA: I do think it's obvious that you shouldn't do option 1 all-things-considered, because of various moral norms other than impartial altruism that scream against that option.) Interested to hear if there's something in your claim that that post fails to address.

Thanks for clarifying, Anthony.

Yes, I do.

Yes, I agree.

I think the vast majority of actions have a probability of being beneficial only slightly above 50 %, as I guess they decrease wild-animal-years, and wild animals have negative lives with a probability slightly above 50 %. However, I would still say there are actions which are robustly beneficial in expectation, such as donating to SWP. It is possible SWP is harmful, but I still think donating to it is robustly better than killing my family, friends, and myself, even in terms of increasing impartial welfare.

Thanks. I will do that.

It's kinda funny to reread this 6 months later. Since then, the sign of your precise best guess flipped twice, right? You argued somewhere (can't find the post) that shrimp welfare actually was slightly net bad after estimating that it increases soil animal populations. Later, you started weakly believing animal farming actually decreases the number of soil nematodes (which morally dominate in your view), which makes shrimp welfare (weakly) good again.

(Just saying this to check if that's accurate because that's interesting. I'm not trying to lead you into a trap where you'd be forced to buy imprecise credences or retract the main opinion you defend in this comment thread. As I suggest in this comment, let's maybe discuss stuff like this on a better occasion.)

I found this funny!

I only looked into the impact of improving the conditions of farmed shrimps (in particular, by electrically stunning them) accounting for shrimps and soil animals in a recent post. However, I mentioned on June 28 "I am glad farmed shrimp are the animal-based food from Poore and Nemecek (2018) requiring the least agricultural land per food-kg. This means replacing farmed shrimp with other animal-based foods tendentially increases cropland, thus having the added benefit of increasing the welfare of soil nematodes, mites, and springtails". I was thinking that increasing cropland would decrease soil-animal-years. I commented on November 3 I am now uncertain about whether increasing agricultural land (cropland or pastures) increases or decreases soil-animal-years.

I have not spent much time figuring out whether my best guess is that increasing agricultural land increases or decreases soil-animal-years. I am sufficiently uncertain to believe the priority is further research on the welfare of soil animals, and what increases or decreases their population.

I was a bit overconfident here, although I flagged I may be wrong (see the 1st sentence of the quote just below). I do not know whether electrically stunning farmed shrimps, which has been the primary outcome of SWP, increases or decreases welfare due to uncertain effects on soil animals.

I still very much stand by this. Killing my family, friends, and myself would not help get more research on how to increase the welfare of soil animals.

At a conceptual level, I think it's worth clarifying that "impartiality" and "impartial altruism" do not imply consequentialism. For example, the following passages seem to use these terms as though they must imply consequentialism. [Edit: Rather, these passages seem to use the terms as though "impartiality" and the like must be focused on consequences.]

Yet there are forms of impartiality and impartial altruism that are not consequentialist in nature [or focused on consequences]. For example, one can be a deontologist who applies the same principles impartially toward everyone (e.g. be an impartial judge in court, treat everyone you meet with the same respect and standards). Such impartiality does not require us to account for all the future impacts we could have on all beings. Likewise, one can be impartially altruistic in a distributive sense — e.g. distributing a given resource equally among reachable recipients — which again does not entail that we account for all future impacts.

I don't think this is merely a conceptual point. For example, most academic philosophers, including academic moral philosophers, are not consequentialists, and I believe many of them would disagree strongly with the claim that impartiality and impartial altruism imply consequentialism.[1] Similarly, while most people responding to the EA survey of 2019 leaned toward consequentialism, it seems that around 20 percent of them leaned toward non-consequentialism, and presumably many of them would also disagree with the above-mentioned claim.

Furthermore, as hinted in another comment, I think this point matters because it seems implied a number of times in this sequence that if we can't ground altruism in very strong forms of consequentialist impartiality, then we have no reason for being altruists and impartial altruism cannot guide us (e.g. "if my arguments hold up, our reason to work on EA causes is undermined"; "impartial altruism would lose action-guiding force"). Those claims seem to assume that all the alternatives are wholly implausible (including consequentialist views that involve weaker or time-adjusted forms of impartiality). But that would be a very strong claim.

They'd probably also take issue with defining an "impartial perspective" as one that is consequentialist: "one that gives moral weight to all consequences, no matter how distant". That seems to define away other kinds of impartial perspectives.

I don't understand why you think this, sorry. "Accounting for all our most significant impacts on all moral patients" doesn't imply consequentialism. Indeed I've deliberately avoiding saying unawareness is a problem for "consequentialists", precisely because non-consequentialists can still take net consequences across the cosmos to be the reason for their preferred intervention. My target audience practically never appeals to distributive impartiality, or impartial application of deontological principles, when justifying EA interventions (and I would be surprised if many people would use the word "altruism" for either of those things). I suppose I could have said "impartial beneficence", but that's not as standard.

Can you say more why you think it's very strong? It's standard within EA to dismiss (e.g.) pure time discounting as deeply morally implausible/arbitrary, and I concur with that near-consensus.[1] (Even if we do allow for views like this, we face the problem that different discount rates will often give opposite verdicts, and it's arbitrary how much meta-normative weight we put on each discount rate.) And I don't expect a sizable fraction of my target audience to appeal to the views you mention as the reasons why they work on EA causes. If you think otherwise, I'm curious for pointers to evidence of this.

Some EAs are sympathetic to discounting in ways that are meant to avoid infinite ethics problems. But I explained in footnote 4 that such views are also vulnerable to cluelessness.

On the first point, you're right, I should have phrased this differently: it's not that those passages imply that impartiality entails consequentialism ("an act is right iff it brings about the best consequences"). What I should have said is that they seem to imply that impartiality at a minimum entails strong forms of consequence-focused impartiality, i.e. the impartiality component of (certain forms of) consequentialism ("impartiality entails that we account for all moral patients, and all the most significant impacts"). My point was that that's not the case; there are forms of impartiality that don't — both weaker consequence-focused notions of impartiality as well as more rule-based notions of impartiality (etc), and these can be relevant to, and potentially help guide, ethics in general and altruism in particular.

I think it's an extremely strong claim both because there's a broad set of alternative views that could potentially justify varieties of impartial altruism and work on EA causes — other than very strong forms of consequence-focused impartiality that require us to account for ~all consequences till the end of time. And the claim isn't just that all those alternative views are somewhat implausible, but that they are all wholly implausible (as seems implied by their exclusion and dismissal in passages like "impartial altruism would lose action-guiding force").

One could perhaps make a strong case for that claim, and maybe most readers on the EA Forum endorse that strong claim. But I think it's an extremely strong claim nevertheless.

To clarify, what I object to here is not a claim like "very strong consequence-focused impartiality is most plausible all things considered", or "alternative views also have serious problems". What I push back against is what I see as an implied brittleness of the general project of effective altruism (broadly construed), along the lines of "it's either very strong consequence-focused impartiality or total bust" when it comes to working on EA causes/pursuing impartial altruism in some form.