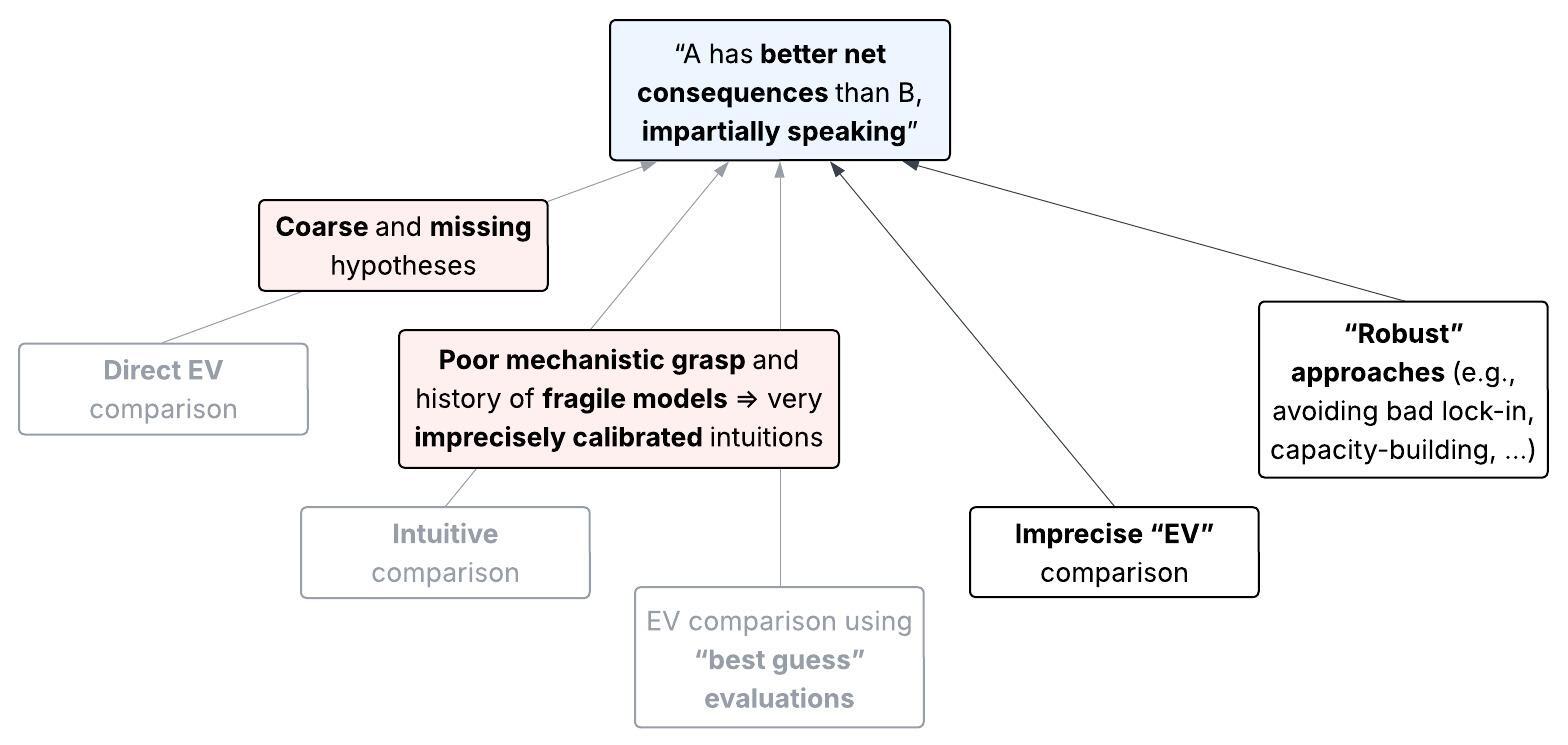

We’ve seen so far that unawareness leaves us with gaps in the impartial altruistic justification for our decisions. It’s fundamentally unclear how the possible outcomes of our actions trade off against each other.

But perhaps this ambiguity doesn’t matter much in practice, since the consequences that predominantly shape the impartial value of the future (“large-scale consequences”, for short) seem at least somewhat foreseeable. Here are two ways we might think we can fill these gaps:

Implicit: “Even if we can’t assign EVs to interventions, we have reason to trust that our pre-theoretic intuitions at least track an intervention’s sign. These intuitions can distinguish whether the large-scale consequences are net-better than inaction.”[1]

- Explicit: “True, we don’t directly conceive of fine-grained possible worlds, only coarse hypotheses. We can still assign precise EVs, though, by intuitively estimating the average value of the possible worlds in each hypothesis. These best-guess estimates will at least be better than chance.”

Do these approaches hold up, when we look concretely at how vast our unawareness could be? “The far future is complex” is a truism that many EAs are probably sick of hearing. But here I’ll argue that this complexity — which also plagues our impact on near-term pivotal events like AI takeoff — specifically undermines both Implicit and Explicit. For instance, we can’t simply say, “It’s intuitively clear that trying to spread altruistic values would be better than doing nothing”, nor, “If it’s better for future agents to be altruistic, we should try to spread altruism, since intuitively this is at least somewhat more likely to succeed than backfire”. This is because our intuitions about large-scale consequences don’t seem to account for unawareness with enough precision. If that’s true, we’ll need a new framework for impartially evaluating our actions under unawareness.

The argument in brief: First, a strategy’s sign from an impartial perspective seems unusually sensitive to factors we’re unaware of, compared to the local perspective we take in more familiar decision problems (cf. Roussos (2021)). Thus it’s unsurprising if our intuitions can justify claims like “ is net-positive” on the local scale, yet don’t justify such claims on the cosmic scale. Second, these intuitions seem so imprecisely calibrated that it doesn’t make sense to bet that they’re “better than chance”. Rather, the signal from these intuitions is drowned out, not by noise, but by systematic reasons why they might deviate from the truth.

Degrees of imprecision from unawareness

Key takeaway

The generalization of “expected value” to the case of unawareness should be imprecise, i.e., not a single number, but an interval. This is because assigning precise values to outcomes we’re not precisely aware of would be arbitrary. This imprecision doesn’t represent uncertainty about some “true EV” we’d endorse with more thought. Rather, it reflects irreducible indeterminacy: there is no single value pinned down by our evidence and epistemic principles.

This post will largely focus on empirical evidence that our unawareness runs deep. First, though, we’ll need a bit of conceptual setup. I made some claims above about “(im)precision”. What exactly does this mean, and why does it matter?

Suppose we had a notion of EV generalized to the case of unawareness — call this unawareness-inclusive expected value (“UEV”). Since our problem is that our value function doesn’t directly give us precise values of hypotheses, a natural move would be to let UEV be an imprecise version of EV. That is, UEV should be an interval, rather than a single number. The width of this interval is the UEV’s degree of imprecision.

Under the hood, both Implicit and Explicit above are claims about degrees of imprecision: “We can conclude some strategy is better than some , without explicitly modeling their UEVs, because we know those UEVs aren’t too imprecise.”[2] (We’ll see how this works in more detail soon.) So, although I’ll defer the full model of UEV to the third post, for now we’ll need the high-level picture.

(Note: The rest of the section reviews ideas I’ve discussed in “Should you go with your best guess?”, from a slightly new angle. Feel free to skip this if you’re familiar with that post.)

How should we interpret “the UEV of strategy is ”? This does not mean “if I thought more, probably I’d consider the UEV to be some number in this interval, but I’m uncertain which one”, or “all values in this interval are equally plausible UEVs”. Instead, our evaluation of the strategy’s “expected” impact is irreducibly indeterminate. We simply don’t narrow it down further. That is, is:

- better than a strategy that guarantees value , and

- worse than a strategy that guarantees value , but

- incomparable with a strategy that guarantees value , for any in . It’s neither better, nor worse, nor exactly as good as that strategy.

And why might the UEV have this structure? Because (we suppose) we can think of some reasons in favor of values closer to , and others in favor of values closer to , and we’re at a loss how to weigh them up. That is, we think any particular way of precisely weighing these reasons would be arbitrary. This was the predicament of our protagonist from the vignette, whose reaction to all their murky information about the sign of working on AI control was “I have no idea”.

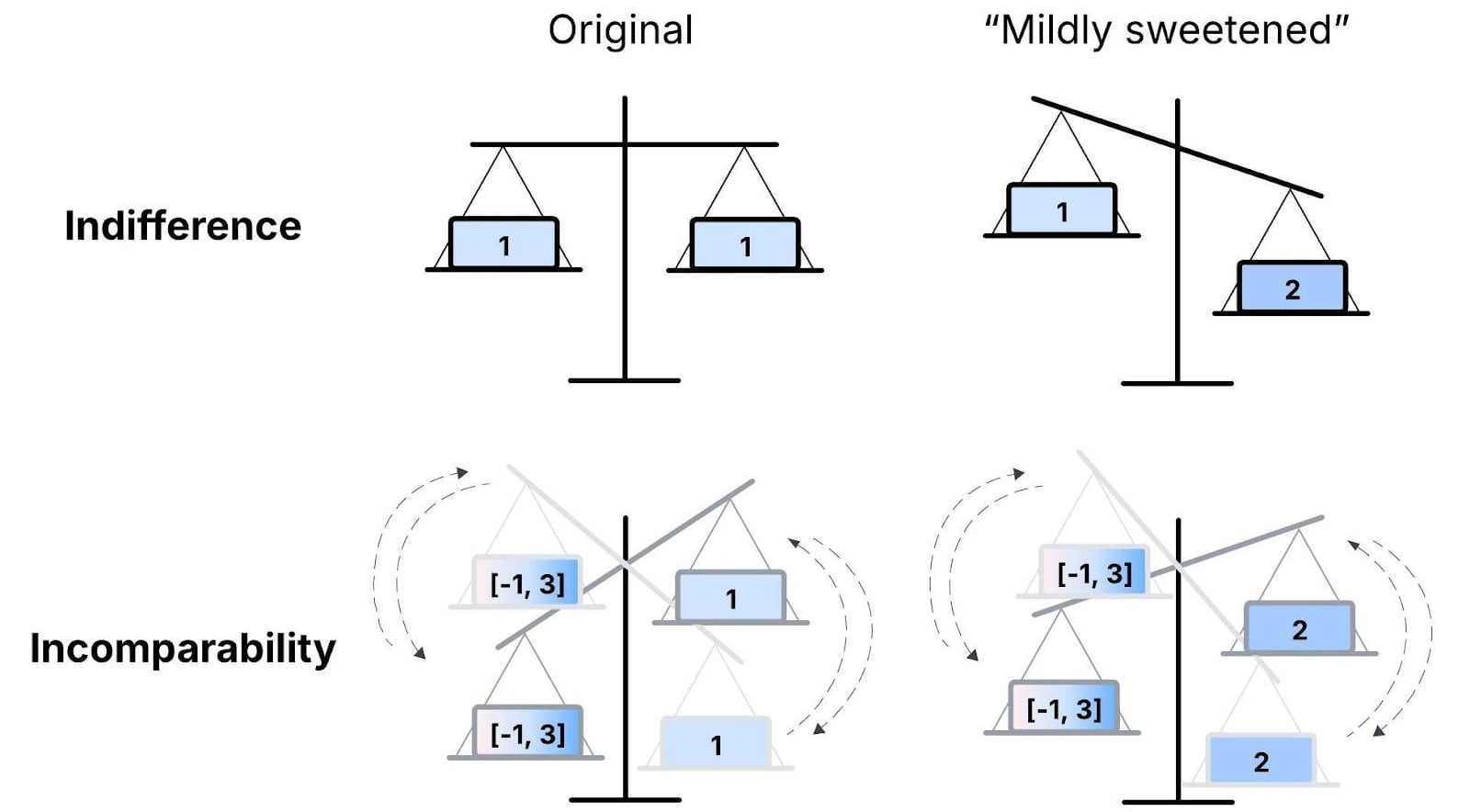

For some more intuition, take Fig. 2, which distinguishes incomparability from indifference. If you’re indifferent between and , a small improvement to (a so-called “mild sweetening”) makes you strictly prefer . Whereas if and are incomparable, they remain incomparable after any sufficiently mild sweetening. For example, it seems natural that if we told the person from the vignette, “By the way, AI control might also slightly harm digital minds”, the appropriate response wouldn’t be, “Ah, AI control is slightly negative, then!” They’d still have no idea. (So, a conclusion as radical as “no strategy is impartially better than any other” doesn’t require all strategies’ UEV to be balanced on a knife edge. Incomparability is much less fragile than precise indifference.)

|

| Figure 2. Indifference between (left “weight”) and (right “weight”) goes away as soon as we mildly improve . Contrast this with incomparability. We can (loosely) visualize this as the relative weights of and “fluctuating” chaotically (dotted arrows), such that doesn’t determinately outweigh or vice versa, nor are they precisely equal. and remain incomparable if the improvement to is sufficiently mild. |

Now, imprecision doesn’t always entail incomparability. You know the Eiffel Tower is taller than the Louvre, without knowing their exact heights. Likewise, we might be able to compare two strategies’ imprecise UEV. Therefore the crux we’ll explore, for the rest of the sequence, is whether we can narrow down some pair of strategies’ UEV precisely enough to compare them. Let’s start by seeing if we can justify such comparisons without explicitly modeling UEV.

When is unawareness not a big deal?

Key takeaway

Suppose we have (A) a deep understanding of the mechanisms determining a strategy’s consequences on some scale, and (B) evidence of consistent success in similar contexts. Then, we can trust that our intuitions factor in unawareness precisely enough to justify comparing strategies, relative to that scale.

The motivation for assigning imprecise UEVs to strategies was to avoid arbitrariness. But isn’t arbitrariness practically unavoidable? After all, we seem justified in taking various common-sense actions — at least with respect to local goals that aren’t concerned with distant consequences. We don’t worry that eating a sandwich could catastrophically backfire on us. So how do we non-arbitrarily bound the probability of something like, “I’m missing a hypothesis that implies this sandwich will kill me”?

The key is that unawareness comes in degrees, based on the scale of consequences a given goal is concerned with. For local goals, our degree of unawareness seems small enough not to be decision-relevant. Here are two reasons why.

Knowledge of mechanisms. First, on local scales, the systems we interact with are simple enough that we can be confident we understand their relevant mechanisms (cf. Bostrom). When you bite into a sandwich, you understand the relevant physical systems well enough to precisely predict that it almost certainly won’t kill you. It would be arbitrary to posit hidden mechanisms that imply drastic deviations from this prediction. We can justify low probabilities on such deviations with the principles we usually use to rule out radical skepticism, like Occam’s razor. While these principles are vaguely specified, they aren’t arbitrary (more discussion here and here). And we have abundant feedback loops on our models of these local systems, which give us tacit knowledge of their mechanisms.

Inductive evidence of success. Second, even when we don’t understand a mundane problem’s mechanisms, we can non-arbitrarily extrapolate from historical successes if there’s no particular reason to think the given problem is disanalogous. Humans have solved countless local-scale problems, and surprises on this scale tend to be minor variations rather than complete reversals of our understanding. This track record gives us strong (yet defeasible) grounds for believing that our local-scale decisions aren’t sensitive to unawareness.[3]

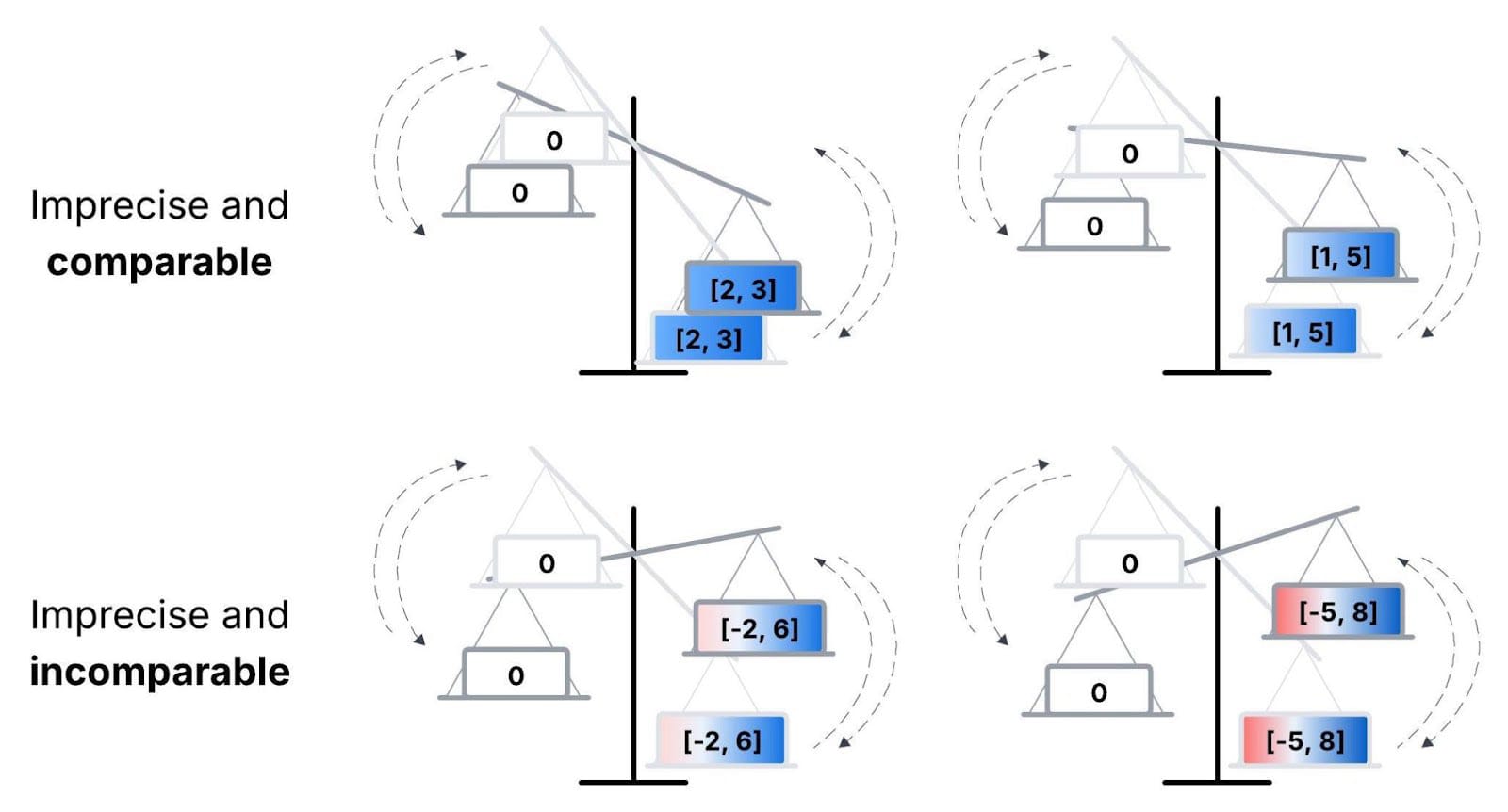

Putting this in terms of the UEV idea: Although even local goals will imply imprecise UEVs, these two considerations suggest that the degree of imprecision is small enough that we can compare our options. See Fig. 3 (top row) for numerical examples. Further, we’re justified in thinking this without explicitly modeling UEV. That is, the Implicit approach does seem reasonable on local scales.

|

Figure 3. With a low degree of imprecision, all possible ways of making a strategy’s UEV precise have the same sign (top). So the strategy’s net impact is comparable with 0, i.e., we can say it’s net-positive.[4] With a high degree of imprecision, though, the ways of making the UEV precise differ in sign (bottom). So the strategy’s sign is indeterminate. |

Why we’re especially unaware of large-scale consequences

And what if we don’t seem to know much about the mechanisms governing our impact on some scale? What if we’ve failed to robustly model these mechanisms in the past? The more strongly these problems apply, the less justified we are in thinking our strategies’ UEVs are precise enough to compare using the Implicit approach (Fig. 3, bottom row). And likewise, we’re less justified in using precise guesses in impact modeling, as in Explicit. I’ll now argue that both problems are severe when we’re evaluating our actions’ large-scale consequences.

Crucially, this concern doesn’t rely on a sudden jump from “intuitions are reliable” to “intuitions are unreliable”. That’s because of insensitivity to mild sweetening: We may have some intuitive reason to prefer some strategy. But we need to weigh that reason against the output of an explicit model of the strategy’s impact. If that model reveals too much imprecision (as I’ll argue in Post #3), then the strategies will be incomparable overall. (More on this later.)

Extremely limited understanding of mechanisms

Key takeaway

Our understanding of our effects on high-stakes outcomes seems too shallow for us to have precisely calibrated intuitions. This is due to the novel and empirically inaccessible dynamics of, e.g., the development of superintelligence, civilization after space colonization, and possible interactions with other universes.

Looking at the mechanisms that might determine our interventions’ large-scale consequences, the “Knowledge of mechanisms” argument seems quite weak on this scale. To see this, consider some domains of interest to impartial altruists (see citations for examples):

- Development of superintelligence: What are all the unintended ways in which advocating for safety interventions could affect the behavior of smarter-than-human AI systems? (Soares; Steiner)

- Civilization after superintelligence: What’s the relative value of a world taken over by different kinds of misaligned AIs or humans (Finnveden; Davidson)? What are all the relevantly distinct ways these variables could play out?: Future reflection on values (Carlsmith); timing of lock-in (Finnveden et al. 2023); competitive pressures (Christiano; Hanson); inter-ASI conflict (Clifton et al.); superalignment failures (Aschenbrenner); and space governance (Moorhouse and MacAskill 2025).

(Even if nothing totally inconceivable happens, the interactions between these variables seem too complex for us to grasp most of the relevant futures in practice.[5])

- Value of the future: What are all the big-picture normative arguments (Nguyen; Beckstead 2013) and empirical considerations (Christiano; Trammell) bearing on whether the future will be net-good?

- Causal and acausal interactions with other space-colonizing civilizations: What are all the possible value systems (Bostrom) and attitudes toward decision theory (Dai) and bargaining that these civilizations might have, and mechanisms selecting for/against each of these? What are all the candidate motivations of agents who might be simulating us (Bostrom 2003)?

- (If we’re truly impartial, we can’t dismiss these “galaxy-brained” considerations out of hand. We can factor them into our overall assessment, without Pascal’s-mugging ourselves by acting on specific hypotheses about these speculative matters (cf. Carlsmith).)

And, we seem to have a thin mechanistic understanding not only of the far future, but also of our impact on possible lock-in events within the next 5-10 years. That might seem like a manageable timescale. But what matters isn’t the time horizon per se, but the number and familiarity of distinct pathways that could unfold. If AGI/ASI takeoff might entail enough technological acceleration that timelines to lock-in are so short, we’re as unaware in this domain as EAs in the year 1900 would’ve been about events a century away.[6] Not to mention, EAs working in global health are all too familiar with how counterintuitively complex even their local cause area is (Wildeford).

I’m not saying, “Look at all this complexity! Ergo, we’re clueless.” My point is: Given so many unfamiliar mechanisms to keep track of with so little (if any) empirical feedback, our intuitions about these mechanisms won’t be calibrated precisely enough to capture the tradeoffs we care about. Nor am I saying the effects we’re unaware of, or coarsely aware of, are mostly negative. Rather, there are many plausible negative effects, and many plausible positive effects, and (on its face) it’s highly ambiguous how they balance out.

Can’t we just do more research? We’ll come back to this in the final post. For now, the relevant question is whether our current epistemic state can justify the claim “strategy has better expected consequences than some alternative”. That includes the strategy “do more research”!

Unawareness and superforecasting

Key takeaway

The mechanisms we’re unaware of might be qualitatively distinct from those we’re aware of. They’re not merely the minor variations we know superforecasters can handle.

(Credit to Jesse Clifton for the key points in this subsection. See also Violet Hour, and my previous discussion here.)

One important objection: I’ve claimed that our conscious mechanistic understanding is far too limited to trust our intuitions about large-scale consequences. But isn’t the track record of superforecasters evidence against this? As Lewis argues, geopolitical forecasting looks pretty complicated, and yet, in this domain one can make significantly better-than-chance precise estimates, e.g., “my median for the end of the Ukraine war is [month] [year]”. And one can do so without explicitly accounting for all possible causal pathways (indeed, even without much thought at all).[7]

However, the question we’re concerned with here is, “For some coarsely specified large-scale consequences that might result from an action, how precisely do our intuitions pin down the value of those consequences?” A few reasons why impressive accuracy in geopolitical forecasting tells us very little about that question:

- “Large-scale consequences”: The problem isn’t that we can’t list every variation on a few basic mechanisms that drive an action’s large-scale consequences. It’s that we can’t conceive of many qualitatively different mechanisms, which could lead to outcomes of very different value. Questions like “How long will the Ukraine war last?” don’t appear nearly as sensitive to such variations as, say, “How likely is pushing for certain AI regulations to cause vs. prevent lock-in of bad values by ASI?”. Geopolitical forecasts don’t depend on how the development of a new intelligent “species” unfolds, or on what happens in other universes. They depend on human interactions driven by social forces we’re somewhat familiar with.

- “How precisely”: The objection is that, based on superforecasting track records, our evaluations of large-scale consequences should have a low degree of imprecision. I think we have (a) little evidence for this claim, and (b) some evidence against it.

Empirical evidence supports a few decimal places of precision for estimates in relatively familiar domains (see, e.g., Friedman (2021, Ch. 3)).[8] I agree this should update us towards “our intuitions can capture complex information with more precision than we’d naïvely expect”. Superforecasting is impressive! Yet that hardly gets us to “our intuitions can pin down values of large-scale consequences precisely enough to let us compare strategies, on impartial grounds”. To say how much precision these intuitions can achieve, we need to look at the structure of the relevant mechanisms, as in (1). (See footnote for more details covered in my previous post.[9])

- Superforecasters’ credences in hypotheses about, e.g., AI risk can vary over several orders of magnitude, despite extensive debate (see here and here). If they could calibrate their intuitions precisely enough to price in all the key AI risk mechanisms, we wouldn’t expect such persistent disagreement. Many other careful thinkers about AI risk mostly disregard superforecasts anyway, because they trust their own understanding of the mechanisms at play. Take Carlsmith: “I remain unsure how much to defer to raw superforecaster numbers (especially for longer-term questions where their track-record is less proven) absent object-level arguments I find persuasive.” Indeed.

Pessimistic induction

Key takeaway

Instead of consistent success, we have a history of consistently fragile models of how to promote the impartial good. Based on EAs’ track record of discovering sign-flipping considerations and new scales of impact, we’re likely unaware of more such discoveries.

How about inductive evidence? Obviously, we have no direct evidence about how well different strategies promote cosmic-scale welfare. As for indirect evidence, we can consider the human history of discovering new hypotheses. I can’t put it better than Greaves and MacAskill (2021, Sec. 7.2):

Consider, for example, would-be longtermists in the Middle Ages. It is plausible that the considerations most relevant to their decision – such as the benefits of science, and therefore the enormous value of efforts to help make the scientific and industrial revolutions happen sooner – would not have been on their radar. Rather, they might instead have backed attempts to spread Christianity, perhaps by violence: a putative route to value that, by our more enlightened lights today, looks wildly off the mark. The suggestion, then, is that our current predicament is relevantly similar to that of our medieval would-be longtermists.

This turns the earlier “Inductive evidence of success” argument on its head. We saw that, based on our past experience of consistently navigating local-scale problems, our intuitive strategy comparisons on that scale are justified. By contrast, humanity’s past experience of realizing we were confused about large-scale consequences undermines these comparisons. More concretely, past discoveries of insights that flipped the apparent sign of interventions are evidence that other such insights may exist. Besides the examples from our previous vignette, some others (see also section “Motivating example” of this post; Wiblin and Todd; and footnote[10]):

Early awareness-raising about AGI x-risk presumably seemed robustly good. But this might have backfired, by facilitating the founding of AGI labs and raising hype about agentic AGI (Berger; Habryka), as well as putting memes about misalignment in pretraining data (Turner). If progress on safety is harder than progress on capabilities, and more people are interested in working on capabilities than safety, these downsides could easily dominate (Hobbhahn and Chan; Nielsen).[11]

- To reduce factory farming, it seems intuitively good to inform others that farmed animals are intelligent. But if people often replace consumption of more intelligent animals with a larger number of smaller animals, this strategy likely increases animal suffering (Charity Entrepreneurship).

- Reducing (non-AI-caused) extinction risk looks negative from a purely suffering-focused perspective (Gloor). But according to some views on the implications of Evidential Cooperation in Large Worlds (Oesterheld 2017), preventing extinction would reduce suffering overall.

Historically, accelerating technological progress seems to have been robustly net-good for humans. But it looks bad if the dominant effect is to accelerate AI progress, reducing our time left to solve alignment. (Or maybe accelerating AI reduces x-risk anyway (Beckstead[12]; Trammell and Aschenbrenner 2024)?)

Perhaps more frequently, we’ve discovered reasons to shrink our estimates of interventions’ intended upsides. Isn’t this irrelevant to an intervention’s sign, though? No, for two reasons:

- Now that the upsides look weaker, the direct downsides of the intervention could outweigh them. E.g., we’ve known for a while that trying to help the U.S. “win the AGI race” against China risks exacerbating competitive dynamics. Recently, however, EAs and rationalists have become more uncertain whether a U.S. AGI project would be much better than a Chinese one anyway (see here and here).

- Even if the intervention’s first-order effects still look net-positive, displacement effects can make it negative overall, as we saw in the vignette. Suppose you previously estimated that marginal work on was slightly better than , and by working on you discourage others from working on . Then, discovering that is now slightly worse than could flip the sign of your work on .

Lastly, sign flips aside, we’ve also repeatedly discovered new scales of consequences that plausibly dominate interventions’ impact. Our impact could be swamped by yet another scale we’re unaware of. Here’s a stereotypical EA journey: You start off excited about reducing global poverty. Then you consider that farmed animals outnumber humans. Then you consider that wild animals really outnumber farmed animals. Then you consider that sentient beings in the far future really really outnumber near-term sentient beings. Okay, surely now at least the laws of physics imply the decision-relevant stakes can’t get any larger? Nope. You then remember acausal decision theories,[13] and consider that sentient beings throughout the whole multiverse could really really really outnumber sentient beings in our lightcone.

Let’s assume the size of our altruistic influence in principle ends there (though, what about “bigger infinities”?). We’re still not in the clear, because the “train to crazy town” might have more stops that affect the bulk of our systematic influence. E.g., the medieval would-be longtermist wouldn’t have been aware of arguments about the hinge of history. And considerations about anthropics and simulations could imply that basically all of our impact occurs under certain kinds of hypotheses (Carlsmith 2022, Ch. 1-2).

|

The “better than chance” argument, and other objections to imprecision

Key takeaway

If we don’t know how to weigh up evidence about our overall impact that points in different directions, then an intuitive precise guess is not a tiebreaker. This intuition is just one more piece of evidence to weigh up.

(Note: This section gives a refresher of concepts from my post “Should you go with your best guess?”. Feel free to skip this if you’re familiar with that post.)

I hope to have shown that when we move from local-scale problems to the scale of the impartial good, we lose our usual justifications for practically ignoring unawareness — i.e., for assuming a low degree of UEV imprecision without more explicitly modeling strategies’ UEV. Despite this, we might have the sense that our intuitions provide some signal, which narrows an imprecise interval down to a number. (This could either be at the level of evaluating the strategy directly (Implicit), or at the level of evaluating hypotheses before computing EV (Explicit).) In response, here’s a quick FAQ about imprecision.

Q1: “Let’s say we consider assigning a strategy the UEV . We have intuitions as to which values in are more or less plausible. If so, don’t we throw out information by sticking with the interval? Why not aggregate with higher-order weights based on these intuitions?”

Because that would merely push the problem back a step. Where do the precise higher-order weights come from? How do you non-arbitrarily pin them down? The fact “your intuitions point toward [value]” is indeed information we shouldn’t throw out. But you can update on this fact, without resolving the indeterminacy of the UEV. (In the image of Fig. 2, you can add a bit of extra weight to one of the scales, and still end up unable to rank the overall weights.) As we’ve seen, it seems implausible that our intuitions would be precisely truth-tracking on net, about the values of the relevant possible worlds. (more[14])

Q2: “While these intuitions may be unreliable, as long as they’re slightly better than chance, isn’t that enough to motivate narrowing down the UEV?”

When I say it’s doubtful our intuitions are “precisely truth-tracking on net”, I mean: There are some reasons to expect the intuitions to point toward the truth, and some reasons to expect them to point away, and it’s unclear how to weigh them up. Not because of some adversarial “anti-truth-tracking” force, but just because the intuitions might track various non-truth things, which we don’t have reason to think cancel out in expectation. So again, the problem recurs: How do we pin down the higher-order judgment, “On net, how strongly do these intuitions track the truth vs. mislead us?” (more)

Q3: “Even if it’s pretty likely true that our intuitions are as imprecisely honed as you say, we’re not certain of that. If, as you’ll argue, we have no action guidance conditional on this claim, shouldn’t we wager on the possibility that it’s false?”

Here, I’ll take “the possibility that it’s false” to be an empirical possibility, not a rejection of the normative epistemic views I advocate. (The latter is more technically subtle, so I’ve deferred it to Appendix A.) The “no action guidance” conclusion that I’ll argue for is incomparability between and , not indifference. But as depicted in Fig. 2, when we have incomparability, adding the information “it’s possible that has higher net impact than ” on top is not a tiebreaker. To argue that the incomparability is resolved, we’d need to argue “it’s likely enough that [our intuitions are sufficiently calibrated that we can infer] has higher net impact than ”.

Q4: “You say it’s arbitrary to pick a precise UEV. Aren’t the endpoints of the interval also arbitrary?”

Yep! The imprecise representation is an imperfect summary of our epistemic state. But we should distinguish two kinds of “arbitrariness”. The arbitrariness involved in formalizing the vague boundaries of our epistemic state is practically unavoidable. That’s because our epistemic principles themselves are vague (see this post). Unlike precise UEV, though, imprecise UEV avoids additional epistemic arbitrariness, by not narrowing things down beyond the point our evidence and principles take us. Or so I’ll argue, in the next post. (more; more)

Q5: “If you have imprecise UEVs, your preferences will violate the completeness axiom (which says all pairs of options are comparable). Doesn’t that make you vulnerable to money pumps?”

No. Money pump arguments for completeness make the implausible assumption that, when you consider incomparable to , you can’t simply pick the option that avoids the money pump. (By doing so, you’re not acting contrary to your preferences at all.[15]) And choosing between and in this way doesn’t imply completeness; see next question. (more; more)

Q6: “Suppose you think you can’t compare and , due to their severely imprecise UEVs. You have to make a choice anyway, so won’t you act as if they’re comparable (that is, as if your preferences are complete)?”

Our question is why we should choose one option vs. another, not what we can be modeled as doing after the fact. You can choose all things considered, without believing is better with respect to the impartial good (as long as isn’t worse). Once your reasons for choice based on the impartial good have gone as far as they can, you might choose among the remaining options based on non-consequentialist or parochially consequentialist reasons. Regardless, the fact that the passage of time forces you to “choose” something is hardly a positive argument for dedicating your career to some cause. (more; more)

Concluding remarks. Here’s what we’ve seen:

- Unawareness doesn’t undermine our reasons to trust common sense in everyday life. Yet it does render common sense a highly imprecise guide when weighing up the factors that dominate our impact on the future. This is the case even when we’re only concerned with whether, say, near-term AI takeoff goes well.

- If we want to estimate an intervention’s net large-scale consequences with any action-guiding level of precision, we’ll have to account for (i) a massive variety of impact pathways and (ii) paradigm-shifting considerations whose basic shape we can’t even see. Our intuitions seem far from adequate for this task. Then, to justify a given intervention, we’ll need an argument far more robust than something like “this lock-in event seems pretty bad across most scenarios I can think of, and trying to stop it will make it slightly less likely”.

In light of all this, what, if anything, can we say about how one strategy’s “expected” impact under unawareness compares to another? That’s for the next post.

Appendix A: The meta-epistemic wager?

Consider a variant of Q3 above:

Q3’: “Even if it’s highly plausible that our epistemic framework ought to be the one you advocate in this sequence, we have some higher-order weight on precise subjective Bayesianism (‘PSB’). If, as you’ll argue, we have no action guidance (from an impartial perspective) conditional on your framework, shouldn’t we wager on PSB? Especially since our impartial altruistic impact is so high-stakes, on PSB.”

Unlike the original Q3, I don’t think this objection is straightforwardly confused about the nature of incomparability. It seems worth investigating further. However, I don’t think this meta-epistemic wager justifies the status quo, for a few reasons:

- Suppose we should indeed wager on some framework according to which, in some sense, we “expect” to have high-stakes impartial altruistic impact. This still leaves a few questions open.

- Recall the two challenges from unawareness I presented before: the coarseness of the hypotheses we’re aware of, and the extreme opacity of the catch-all. What exactly is our response to these challenges? How do we decide between the approaches I critique in the final post, if any? How should we think about the value of information of research, or scenario planning, or deliberating on our precise guesses, under unawareness? I think we should sit with this situation, before leaping to wager on (our current conception of) PSB specifically.

- When some action is “high stakes” from the PSB perspective, I’m not convinced we should consider this action high-stakes for the purposes of intertheoretic comparisons.

- First, setting aside stakes for a moment, why would the meta-epistemic wager work where the empirical wager fails? The logic seems to be, “My reasons for intervening under PSB shouldn’t be ‘infected’ by the incomparability that the imprecise framework produces. That is, these reasons shouldn’t be lumped together with the imprecise perspective’s pile of reasons for vs. against intervening. That’s because PSB reasons are qualitatively different from imprecise Bayesian reasons.”

- I’m definitely sympathetic to that logic as far as it goes. (I implicitly invoke similar logic here, and in the conclusion of this sequence.) But if these frameworks are indeed qualitatively different, it’s not clear how we can say, “The moral weight of (i) your expected impartial impact from the PSB perspective overwhelms the moral weight of (ii) e.g., your parochial or non-consequentialist reasons.” The notion of greater weight, here, presumes a (controversial) way of comparing apples and oranges.

- Moreover, the motivation for impartial altruism, and the reason its verdicts seem so overwhelmingly weighty, is rejection of arbitrariness. If arbitrariness is (ahem) precisely what PSB unflinchingly embraces, I’m not sure why we should take PSB’s verdict to be overwhelmingly weighty, all things considered. (I’m not too confident in this reply, though. The question of how to adjudicate between different first-order normative perspectives, without smuggling in one of those perspectives, is intrinsically vexing.)

References

Beckstead, Nicholas. 2013. “On the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future.” https://doi.org/10.7282/T35M649T.

Bostrom, Nick. 2003. “Are We Living in a Computer Simulation?” The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-) 53 (211): 243–55.

Carlsmith, Joseph. 2022. “A Stranger Priority? Topics at the Outer Reaches of Effective Altruism.” University of Oxford.

Davidson, Tom, Lukas Finnveden, and Rose Hadshar. 2025. “AI-Enabled Coups: How a Small Group Could Use AI to Seize Power.” https://www.forethought.org/research/ai-enabled-coups-how-a-small-group-could-use-ai-to-seize-power.

Finnveden, Lukas, Jess Riedel, and Carl Shulman. 2023. “AGI and Lock-In.” https://www.forethought.org/research/agi-and-lock-in.

Friederich, Simon. 2025. “Causation, Cluelessness, and the Long Term.” Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy 12.

Friedman, Jeffrey A. 2021. War and Chance. Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, Paul, and George Wright. 2010. “The limits of forecasting methods in anticipating rare events.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 77 (3): 355-368.

Grant, Simon, and John Quiggin. 2013. “Inductive Reasoning about Unawareness.” Econom. Theory 54 (3): 717–55.

Greaves, Hilary, and William MacAskill. 2021. “The Case for Strong Longtermism.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 5-2021, University of Oxford.

Hedden, Brian. 2015. “Time-Slice Rationality.” Mind; a Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy 124 (494): 449–91.

Mogensen, Andreas, and David Thorstad. 2020. “Tough enough? Robust satisficing as a decision norm for long-term policy analysis.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 15-2020, University of Oxford.

Moorhouse, Fin, and William MacAskill. 2025. “Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion.” https://www.forethought.org/research/preparing-for-the-intelligence-explosion.

Oesterheld, Caspar. 2017. “Multiverse-Wide Cooperation via Correlated Decision Making.” https://longtermrisk.org/files/Multiverse-wide-Cooperation-via-Correlated-Decision-Making.pdf.

Rabinowicz, Wlodek. 2020. “Between Sophistication and Resolution: Wise Choice.” In The Routledge Handbook of Practical Reason, 526–40. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

Roussos, Joe. 2021. “Unawareness for Longtermists.” 7th Oxford Workshop on Global Priorities Research. June 24, 2021. https://joeroussos.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/210624-Roussos-GPI-Unawareness-and-longtermism.pdf.

Schwitzgebel, Eric. 2024. “The Washout Argument Against Longtermism.” Working paper. https://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~eschwitz/SchwitzPapers/WashoutLongtermism-240621.pdf.

Trammell, Philip, and Leopold Aschenbrenner. 2024. “Existential Risk and Growth.” Global Priorities Institute Working Paper No. 13-2024, University of Oxford.

- ^

A more precise version of this claim: “Our intuitions can distinguish whether we’d be justified in considering large-scale consequences net-better than inaction, if we more explicitly evaluated these consequences.”

- ^

Analogously, you might say, “I know this heuristic tracks an action’s EV well enough that I can tell s1 has higher EV, without literally computing the EV.”

- ^

See Grant and Quiggin (2013) for more.

- ^

I’ve oversimplified this for ease of exposition. When we say a strategy is “net-positive”, we’re actually comparing it with some “inaction” alternative, which will in general also have an imprecise UEV, not a precise UEV of 0.

- ^

H/t Anni Leskelä.

- ^

H/t Clare Harris for prompting this point.

- ^

Quote: “There are obvious things one can investigate to get a better handle on the referendum question above… Yet I threw out an estimate without doing any of these… As best as I can tell, these snap judgements (especially from superforecasters, but also from less trained or untrained individuals) still comfortably beat chance.”

- ^

When I say that “evidence supports” some degree of imprecision, this isn’t a purely empirical claim. Strictly speaking, the claim is “the evidence supports some degree of imprecision, given some epistemic principles that I think are generous to the high-precision view”.

- ^

Unlike forecasting individual events, estimating expected values requires estimating a variety of factors. Even if the estimate of each factor is only mildly imprecise, these low degrees of imprecision can collectively lead to high imprecision in the overall estimate. Moreover, unlike forecasting the unconditional likelihood of some event (e.g., “misaligned ASI takes over”), here we need to compare the likelihoods of very rare counterfactual impacts (e.g., “advocating for this eval prevents a misaligned ASI takeover” or “advocating for this eval causes a misaligned ASI takeover”). I’m not aware of any evidence that events this unlikely can be predicted to a high degree of precision. Indeed, see Goodwin and Wright (2010) for the opposite case.

- ^

Further examples:

- Bostrom gives an extended example of sign-flipping considerations about the value of developing nanotechnology.

- EA movement-building would’ve seemed like a no-brainer meta cause, before the FTX fiasco and subsequent backlash against EA and longtermism (Morrison).

- In 2024, many in the AI risk community grew sympathetic to U.S. nationalization of AGI projects, in order to outcompete China (Aschenbrenner). But if China looks sufficiently unlikely to (say) have enough compute to build AGI first, the dominant effect of nationalization might instead be to exacerbate AI-enabled coup risk (Davidson et al. 2025).

- (H/t Sylvester Kollin.) Miscellaneous examples surveyed in Friederich (2025, Sec. 5), e.g., attention hazards and dual-use technologies relevant to anthropogenic x-risks.

- (H/t Jim Buhler.) Schwitzgebel’s (2024) “Nuclear Catastrophe Argument”: Preventing an earlier nuclear war involving weaker weapons looks plausibly bad if, had this war occurred, it would have served as a “warning shot” that motivated humanity to prevent more destructive wars later on.

- ^

H/t Anni Leskelä.

- ^

Quote (emphasis mine): “I found that speeding up advanced artificial intelligence—according to my simple interpretation of these survey results—could easily result in reduced net exposure to the most extreme global catastrophic risks (e.g., those that could cause human extinction), and that what one believes on this topic is highly sensitive to some very difficult-to-estimate parameters (so that other estimates of those parameters could yield the opposite conclusion).”

- ^

Okay, this part isn’t so stereotypical!

- ^

See also Mogensen and Thorstad (2020, Sec. 4.3): “[I]t seems implausible to require precise second-order probabilities while conceding that our evidence is so incomplete and/or ambiguous that no precise probability assignment over the relevant first-order hypotheses is warranted by our evidence. In fact, there is a strong case to be made that this is simply incoherent.”

- ^

See Bradley, and Rabinowicz (2020). For a defense of a perspective on which there are no rational requirements to avoid sequential money pumps in the first place, see Hedden (2015).

Imagine my UEVs for the mass of objects A and B are [0.95, 1.05] and [1, 1.1] kg. Would your framework suggest the expected mass of the objects is incomparable because my UEVs overlap in [1, 1.05] kg? I think so. However, given any 2 objects, I believe my best guess should be that the expected mass of one is smaller, equal, or larger than that of the other.

Yes, for the expected mass.

Why? (The actual mass must be either smaller, equal, or larger, but I don't see why that should imply that the expected mass is.)

I did mean the expected mass. I have clarified this in my comment now.

What do you mean by actual mass? Possible mass? The expected mass is the mean of the possible masses weighted by their probability. I think expected masses are comparable because possible masses are comparable.

The mass that the object in fact has. :) Sorry, not sure I understand the confusion.

I don't think this follows. I'm interested in your responses to the arguments I give for the framework in this post.

I think the term actual value is usually used to describe a possible and discrete value. However, by actual value, you mean a set of possible values, one for each of the distributions describing the mass of a single object? There has to be more than one distribution describing the mass for the expected mass not to be discrete. If that is what you mean by actual value, the actual masses of 2 objects are not necessarily comparable under your framework? If I understood correctly what you mean by actual value, and you still hold that the actual masses of 2 objects are always comparable, why would weighted sums of actual masses representing expected masses not be comparable?

I can see expected masses being incomparable in principle. It seems that gravitons are the least massive entities, and the upper bound for the mass of one is currently 1.07*10^-67 kg. So I assume we cannot currently distinguish between, for example, 10^-100 and 10^-99 kg. Yet, the expected masses of objects I can pick are practically discrete, and therefore comparable, even if I feel exactly the same about the mass of the objects. I would argue the welfare of possible futures is comparable for the same reasons.

No, I mean just one value.

Sorry, by "expected" I meant imprecise expectation, since you gave intervals in your initial comment. Imprecise expectations are incomparable for the reasons given in the post — I worry we're talking past each other.

I see. You are using the term actual value as it is usually used. What do you think about the 2nd paragraph of my last comment?

The framework seems quite reasonable in principle, but I believe you are overestimating a lot the degree of imprecision (irreducible uncertainty) in practice. It looks like you are inferring the value of many possible futures is incomparable essentially because it feels very hard to compare their expected values (EVs), and therefore any choice of which one has the highest EV feels very arbitrary. In contrast, I see arbitrary choices as a reason for further research to decrease their uncertainty, and I expect this is overwhelmingly reducible. Without using any instruments, it would feel very arbitrary to pick which one of 2 identical objects with 1 and 1.001 kg is the heaviest, but this does not mean their mass is incomparable. For most practical purposes, I can assume their mass is the same. I can also use a sufficiently powerful scale in case a small difference would matter. If their mass was sufficiently close, like if it differed by only 10^-100 kg, I agree they may be incomparable, but I do not see this being relevant in practice.

First, it's already very big-if-true if all EA intervention candidates other than "do more research" are incomparable with inaction.

Second, "do more research" is itself an action whose sign seems intractably sensitive to things we're unaware of. I discuss this here.

To clarify, I think any actions people consider in practice are comparable, not only impact-focussed ones involving research.

On the value of research, it again looks like you are inferring the value of many possible futures is incomparable essentially because it feels very hard to compare their EVs.

I don't know exactly what you mean by "feels very hard to compare". I'd appreciate more direct responses to the arguments in this post, namely, about how the comparison seems arbitrary.

It looks like you are inferring incomparability between the value of 2 futures (non-discrete overlap between their UEVs) from the subjective feeling (in your mind) that their EVs feel very hard to compare (given all the evidence you considered), as any comparisons involve decisive arbitrary assumptions. I mean "arbitrary" as used in common language.

Comparisons among the expected cost-effectiveness of the vast majority of interventions seem arbitrary to me too due to effects on soil animals and microorganisms. However, the same goes for comparisons among the expected mass of seemingly identical objects with a similar mass if I can only assess their mass using my hands, but this does not mean their mass is incomparable. To assess this, we have to empirically determine which fraction of the uncertainty in their mass is irreducible. 10 k years ago, it would not have been possible to determine which of 2 rocks with around 1 kg was the heaviest if their mass only differed by 10^-6 kg. Yet, this is possible today. Some semi-micro balances have a resolution of 0.01 mg, 10^-8 kg. So I would say the expected mass of the rocks was comparable 10 k years ago. Do you agree? There could be some irreducible uncertainty in the mass of the rocks, but much less than suggested by the evidence available 10 k years ago.

(Sorry, due to lack of time I don't expect I'll reply further. But thank you for the discussion! A quick note:)

EV is subjective. I'd recommend this post for more on this.

You are welcome to return to this later. I would be curious to know your thoughts.

I liked the post. I agree EV is subjective to some extent. The same goes for the concept of mass, which depends on our imperfect understanding of physics. However, the expected mass of objects is still comparable, unless there is only an infinitesimal difference between their mass.

Did you mean "better or equal" in the 1st bullet, and "worse or equal" in the 2nd bullet?

yep, thanks!

Thanks for the post, Anthony. Sorry for repeating myself, but I want to make sure I understood the consequences of what you are proposing. Consider these 2 options for what I could do tomorrow:

My understanding is that you think it is "irreducibly indeterminate" which of the above is better to increase expected impartial welfare, whereas I believe the 2nd option is clearly better. Did I get the implications of your position right?

That's right. I don't expect you to be convinced of this by the end of this post, to be clear (though I also don't understand why you think it's "clearly" false).

("To increase expected impartial welfare" is the key phrase. Given that other normative views we endorse still prohibit option #1 — including simply "my conscience strongly speaks against this" — it seems fine that impartial altruism is silent. (Indeed, that's pretty unsurprising given how weird a view it is.))

Thanks for clarifying, Anthony. Do you think it is also irreducibly indeterminate which of the following actions is better to increase impartial welfare neglecting effects after their end?

I think listening to music would result in more impartial welfare than torturing a person, even considering effects across all space and time. I understand you think it is irreducibly indeterminate which leads to more impartial welfare in this case, but I wonder whether ignoring the effects after the actions have ended would break the indeterminacy for you. If so, for how long would the effects after the actions have to be taken into account for your indeterminacy to come back? Why?

Ignoring everything after 1 min, yeah I'd be very confident listening to music is better. :) You could technically still say "what if you're in a simulation and the simulators severely punish listening to music," but this seems to be the sort of contrived hypothesis that Occam's razor can practically rule out (ETA: not sure I endorse this part, I think the footnote is more on-point).[1]

In principle, we could answer this by:

(Of course, that's intractable in practice, but there's a non-arbitrary boundary between "comparable" and "incomparable" that falls out of my framework. Just like there's a non-arbitrary boundary between precise beliefs that would imply positive vs. negative EV. We don't need to compute T* in order to see that there's incomparability when we consider T = ∞. (I might be missing the point of your question, though!))

Or, if that's false, presumably these weird hypotheses are just as much of a puzzle for precise Bayesianism (or similar) too, if not worse?

I agree there is be a non-arbitrary boundary between "comparable" and "incomparable" that results from your framework. However, I think the empirics of some comparisons like the one above are such that we can still non-arbitrarily say that one option is better than the other for an infinite time horizon. Which empirical beliefs you hold would have to change for this to be the case? For me, the crucial consideration is whether the expected effects of actions decrease or increase over time and space. I think they decrease, and that one can get a sufficiently good grasp of the dominant nearterm effects to meaningfully compare actions.

For starters, we'd either need:

(Sorry if this is more high-level than you're asking for. The concrete empirical factors are elaborated in the linked section.)

Re: your claim that "expected effects of actions decrease over time and space": To me the various mechanisms for potential lock-in within our lifetimes seem not too implausible. So it seems overconfident to have a vanishingly small credence that your action makes the difference between two futures of astronomically different value. See also Mogensen's examples of mechanisms by which an AMF donation could affect extinction risk. But please let me know if there's some nuance in the arguments of the posts you linked that I'm not addressing.

As far as I can tell, the factors you mention refer to the possibility of influencing astronomically valuable worlds. I agree locking in some properties of the world may be possible. However, even in this case, I would expect the interventions causing the lock-in to increase the probability of astronomically valuable worlds by an astronomically small amount. I think the counterfactual interventions would cause a similarly valuable lock-in slightly later, and that the difference between the factual and counterfactual expected impartial welfare would quickly tend to 0 over time, such that is is negligible after 100 years or so.