[Cross-posted from my Substack here]

If you spend time with people trying to change the world, you’ll come to an interesting conundrum: Various advocacy groups reference previous successful social movements as to why their chosen strategy is the most important one. Yet, these groups often follow wildly different strategies from each other to achieve social change. So, which one of them is right?

The answer is all of them and none of them.

This is because many people use research and historical movements to justify their pre-existing beliefs about how social change happens. Simply, you can find a case study to fit most plausible theories of how social change happens. For example, the groups might say:

- Repeated nonviolent disruption is the key to social change, citing the Freedom Riders from the civil rights Movement or Act Up! from the gay rights movement.

- Technological progress is what drives improvements in the human condition if you consider the development of the contraceptive pill funded by Katharine McCormick.

- Organising and base-building is how change happens, as inspired by Ella Baker, the NAACP or Cesar Chavez from the United Workers Movement.

- Insider advocacy is the real secret of social movements – look no further than how influential the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights was in passing the Civil Rights Acts of 1960 & 1964.

- Democratic participation is the backbone of social change – just look at how Ireland lifted a ban on abortion via a Citizen’s Assembly.

- And so on…

To paint this picture, we can see this in action below:

Source: Just Stop Oil which focuses on…civil resistance and disruption

Source: The Civic Power Fund which focuses on… local organising

What do we take away from all this? In my mind, a few key things:

- Many different approaches have worked in changing the world so we should be humble and not assume we are doing The Most Important Thing

- The case studies we focus on are likely confirmation bias, where we are simply cherry-picking examples (consciously or subconsciously) that confirm our pre-existing beliefs. For example, people often don’t mention the examples where their chosen strategy failed to yield results (e.g. democracy protests which end in more authoritarian regimes or a local legal battle which leads to national legislation opposite to what you want)

- Be very sceptical when anyone, including ourselves, says that a strategy is “the most effective”

In reality, for almost every social issue, we have no clue what “the most effective” strategy is at any one time. The importance of context and relevance likely trumps lessons from previous movements (we have some research highlighting this!). As such, it makes sense to be open-minded to other approaches and not dogmatically preach your favourite strategy.

The response to this is not to think “oh let’s forsake doing research and learning from history” or “everything is equally effective” but rather, we should ask ourselves “Did I just find some notable examples that back up my beliefs or did I consider the most relevant social movements to my issue and methodically study the strategies used?”. (However, the rarity of this latter approach is one reason why the longer I’ve spent in the world of social movement research, the more jaded I’ve become about how research is used).[1]

In brief, I am advocating for more of us to drop our “soldier mindsets”, where we defend our beliefs against any evidence or arguments that might threaten them. Instead, we should adopt a scout mindset, where we seek to see things as they are, not as we wish they were.

I’ve fallen foul of this plenty of times. I remember times when I wanted to prove to someone that (for example) sugar is less worse than artificial sweeteners so I’ll google “is sugar worse than artificial sweeteners” then scan the links to find one that agrees with me. I don’t think I’m alone in this practice.

Julia Galef, author of “The Scout Mindset”, which I highly recommend reading, offers some tips and mindset shifts to support us:

- "Must I believe it?" rather than “Can I believe it?”

- In motivated reasoning, we disproportionately put our effort into finding evidence that supports what we wish were true. However, asking ourselves the simple question of "Must I believe it?" rather than “Can I believe it?” can prove powerful.

- The selective skeptic test: "Imagine this evidence supported the other side. How credible would you find it then?"

- Personally, I see many cases where advocates will repeatedly share a somewhat dodgy study that agrees with their beliefs but when there is a less favourable study, they will get into the weeds that the methodology wasn’t perfect, the sample size was too small, the authors overlooked some key considerations, and so on. In an ideal world, we treat all studies, regardless of result, with the same rigour!

- Hold your identity lightly

- One reason why it can be quite hard to engage with content that disagrees with your worldview is that you’ve constructed your entire identity around that worldview being true.

- For example, I lay out in a previous piece that if you’ve spent years campaigning using a particular approach, been arrested multiple times or taken other high-sacrifice actions, it can be very hard to admit you may have been wrong and all of that was unnecessary. To get around this issue, Julia Galef recommends “Holding your identity lightly means thinking of it in a matter-of-fact way, rather than as a central source of pride and meaning in your life. It's a description, not a flag to be waved proudly.”

- As one example, I’ve shifted away from labeling myself as “radical” or chasing “radical solutions”, so I can also think about ways to improve the world that allow for compromise, flexibility and incremental progress.

- I think there are some tensions with holding your identity lightly and taking high-sacrifice actions, which can be valuable. However, there are also significant downsides to being so fixated on a single worldview that you don’t change your mind when confronted with new evidence.

- Engage with people you disagree with

- This sounds obvious, but sadly, it is pretty common for people to become siloed within ideological containers (e.g. your friendship group, your workplace or your advocacy community). Deliberately engaging with people who don’t share your worldview can help you appreciate different perspectives and challenge your own thinking (and groupthink you may be subject to).

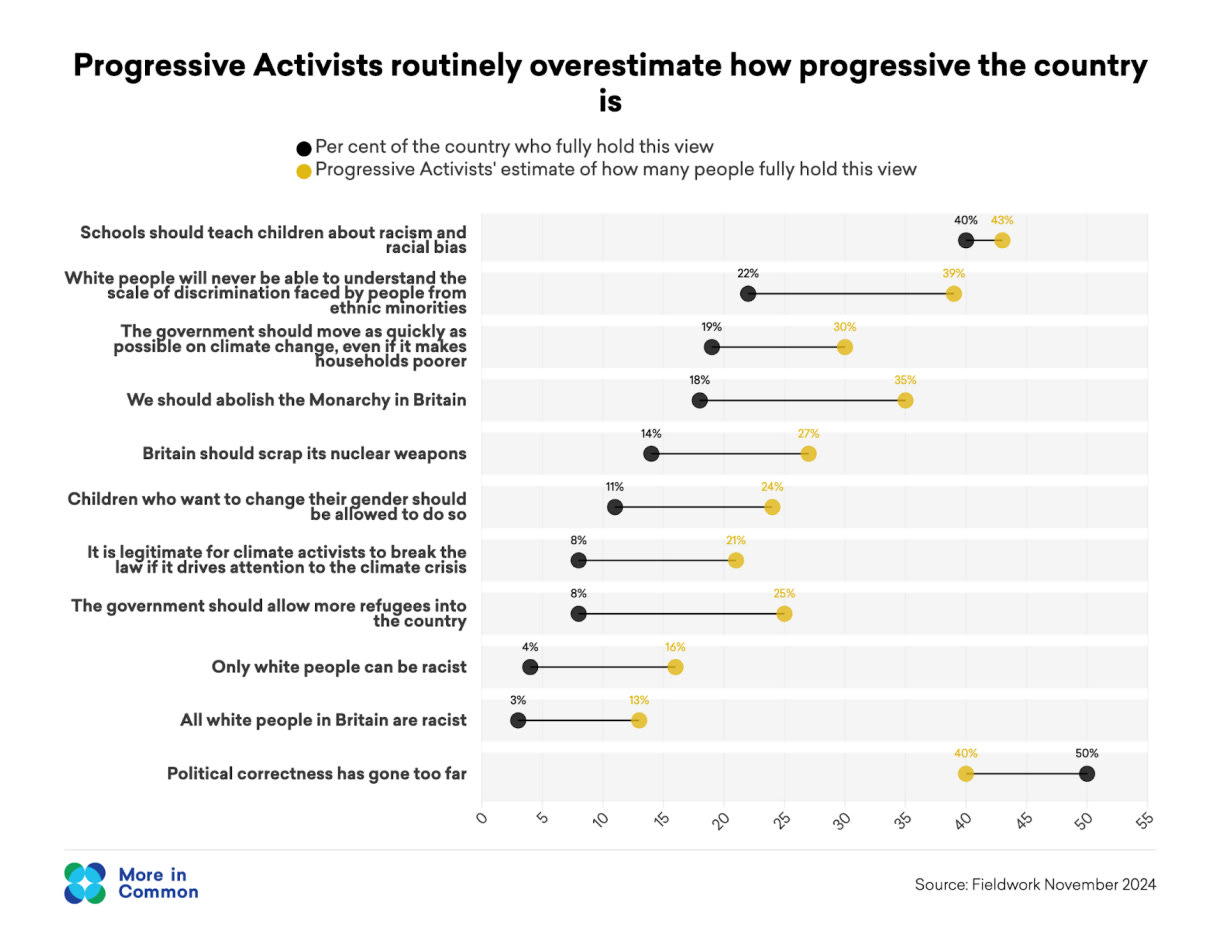

- One example of the consequences of not doing this is shown below in this research by More In Common, which shows Progressive Activists regularly overestimate how much of the country agrees with them.

- Not engaging with people you disagree with likely makes you a worse advocate for your issue, as you don’t fully appreciate their viewpoints and instead caricature them (as I often have done with NIMBYs, but this podcast did a great job of highlighting the very real concerns NIMBYs have which changed my mind on how to best approach NIMBYism).

For more on this, see a great summary of The Scout Mindset here. This essay was inspired by this comment from Lewis Bollard, making the same point in far fewer words!

- ^

As an aside, I think there are research methods that are more immune to this problem. For example, doing a literature review where, before you start, you have clearly specified inclusion criteria of what counts as relevant evidence and how you will weigh up the results. Or doing a pre-registration where you clarify how you will carry out and analyse an experiment before you even collect results. We at Social Change Lab do this for all of our experiments and polling projects (e.g. here).

Executive summary: This exploratory post argues that many social change advocates selectively invoke historical movements to justify their preferred strategies, cautioning that no single approach is universally “most effective” and urging a more open-minded, evidence-based, and context-sensitive mindset in advocacy work.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.