Total vs average utilitarianism

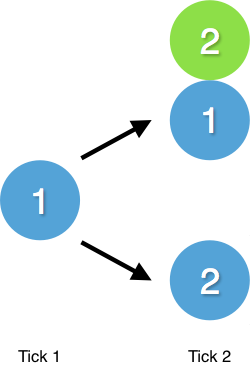

Say you have one utility (think of utility as happiness points) and you have to choose between either creating another person that has two utility, or increasing your own utility to two.

A total utilitarian would choose the first option. It's the one that generates the highest amount of total utility in the next tick (the next moment in time). An average utilitarian would choose the second option since it generates the highest amount of average utility in the next tick.

Here these two theories argue for how we should aggregate utility for the next moment in time. But how should we aggregate utility over a period of time?

Introducing timeline utilitarianism

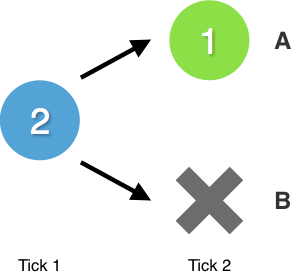

Say you are about to die and you have two utility. You have to choose between either just dying, or dying while creating another person that has one utility.

Let's look at how a timeline can aggregate the total amount of utility.

Timeline A has two ticks. You could aggregate the total amount of utility of this timeline by simply adding the two ticks together (2+1). Let's call this method of aggregating "total timeline utilitarianism". Here we can see that timeline A would be a better choice than timeline B since timeline B only has one tick and therefore only two utility.

You could also aggregate the utility of timeline A by taking the average of the two ticks ((2+1)÷2). Let's call this method of aggregating "average timeline utilitarianism". Here we can see that timeline B would be a better choice than timeline A since timeline B only has one tick and therefore two utility.

Combining moment and timeline utilitarianism

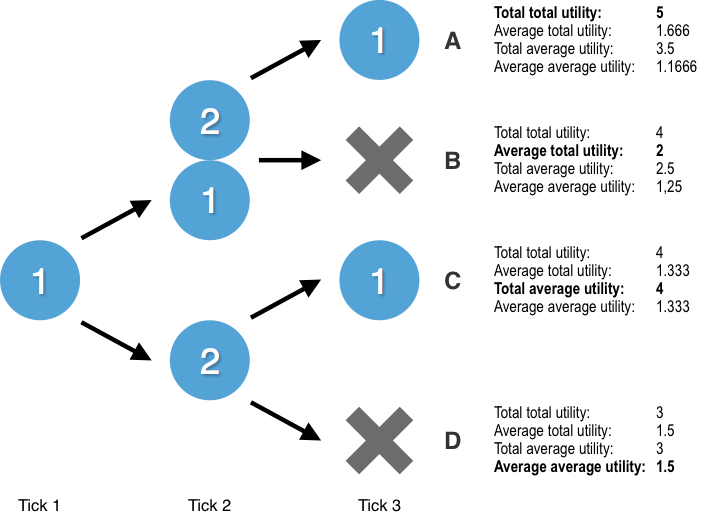

So we have "moment utilitarianism" to look at moments in time and "timeline utilitarianism" to look at the entire timeline. What happens if we combine them? Let's introduce some terms. In "total average utilitarianism" the "total" refers to how we should aggregate the entire timeline. The "average" refers to how we should aggregate the individual moments. I will always mention the timeline aggregation first and the moment aggregation second. There are four different combinations that all make different claims about how we should act.

If we want to maximize total total utility we should choose timeline A. If we want maximize average total utility we should choose timeline B. If we want to maximize total average utility we should choose timeline C. If we want to maximize average average utility we should choose timeline D.

Usually when people talk about different types of utilitarianism they automatically presuppose "total timeline utilitarianism". In fact, the current debate between total and average utilitarianism is actually a debate between "total total utilitarianism" and "total average utilitarianism". I hope this post has pointed out that this assumption isn't the only option.

Wrapping up

In reality we have many more options to choose from and we will have to do complicated probability calculations under uncertainty instead of following a simple decision tree. Some might argue that non-existence should count as zero utility. Some might argue for more exotic forms of utilitarianism like median or mode utilitarianism (I hope you don't spend too much time fretting over which of these options is the "correct" form of utilitarianism and adopt something like meta-preference utilitarianism instead). This is just a simplified model to introduce the concept of timeline utilitarianism. In future posts I will expand on this concept and explore how it interacts with things like hingeyness and choice under uncertainty.

The question of how to aggregate over time may even have important consequences for population ethics paradoxes. You might be interested in reading Vanessa Kosoy's theory here in which she sums an individual's utility over time with an increasing penalty over life-span. Although I'm not clear on the justification for these choices, the consequences may be appealing to many: Vanessa, herself, emphasizes the consequences on evaluating astronomical waste and factory farming.