This post sets out the Happier Lives Institute’s charity recommendation for 2022, how we got here, and what’s next. We provide a summary first, followed by a more detailed version.

Summary

- HLI’s charity recommendation for 2022 is StrongMinds, a non-profit that provides group psychotherapy for women in Uganda and Zambia who are struggling with depression.

- We compared StrongMinds to three interventions that have been recommended by GiveWell as being amongst the most cost-effective in the world: cash transfers, deworming pills, and anti-malarial bednets. We find that StrongMinds is more cost-effective (in almost all cases).

- HLI is pioneering a new and improved approach to evaluating charities. We focus directly on what really matters, how much they improve people’s happiness, rather than on health or wealth. We measure effectiveness in WELLBYs (wellbeing-adjusted life years).

- We estimate that StrongMinds is ~10x more cost-effective than GiveDirectly, which provides cash transfers. StrongMinds’ 8-10 week programme of group interpersonal therapy has a slightly larger effect than a $1,000 cash transfer but costs only $170 per person to deliver.

- For deworming, our analysis finds it has a small but statistically non-significant effect on happiness. Even if we assume this effect is true, deworming is still half as cost-effective as StrongMinds.

- In our new report, The Elephant in the Bednet, we show that the relative value of life-extending and life-improving interventions depends very heavily on the philosophical assumptions you make. This issue is usually glossed over and there is no simple answer.

- We conclude that the Against Malaria Foundation is less cost-effective than StrongMinds under almost all assumptions. We expect this conclusion will similarly apply to the other life-extending charities recommended by GiveWell.

- HLI’s original mission, when we started three years ago, was to take what appeared to be the world’s top charities - the ones GiveWell recommended - reevaluate them in terms of subjective wellbeing, and then try to find something better. We believe we’ve now accomplished that mission: treating depression at scale allows you to do even more good with your money.

- We’re now moving to ‘Phase 2’, analysing a wider range of interventions and charities in WELLBYs to find even better opportunities for donors.

- StrongMinds aims to raise $20 million over the next two years and there’s over $800,000 of matching funds available for StrongMinds this giving season.

Why does HLI exist?

The Happier Lives Institute advises donors how to maximise the impact of their donations. Our distinctive approach is to focus directly on what really matters to people, improving their subjective wellbeing, how they feel during and about their lives. The idea that we should take happiness seriously is simple:

- Happiness matters. Although it’s common to think about impact in terms of health and wealth, those are just a means, not an end in themselves. What’s really important is that people enjoy their lives and are free from suffering.

- We can measure happiness by asking people how they feel. Lots of research has shown that subjective wellbeing surveys are scientifically valid (e.g. OECD, 2013; Kaiser & Oswald, 2022). A typical question is, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life, nowadays?” (0 - not at all satisfied, 10 - completely satisfied).

- Our expectations about happiness are often wrong. When we try to guess what life would be like, for others or our future selves, we suffer from biases. When we put ourselves in other people’s shoes, we put ourselves in their shoes.

Taking happiness seriously means setting priorities using the evidence on what makes people happier - not just looking at measures of health or wealth and combining that with our guesswork.

We calculate the cost-effectiveness of charities in terms of WELLBYs (wellbeing-adjusted life years). 1 WELLBY is equivalent to a 1-point increase for 1 year on a 0-10 life satisfaction scale. A 0.5-point increase for 2 years would also be 1 WELLBY, and so on.

We’re not the first to use this approach (e.g. HRI, 2020; UK Treasury, 2022). The WELLBY is a natural improvement on the QALY (quality-adjusted life year) metric that’s been used in health policy for three decades (Frijters et al., 2020). We are, however, the first to use WELLBYs to work out the best way to spend money to help others, wherever they are in the world.

We thought the best place to start was by taking the existing charity recommendations made by GiveWell, a leading charity evaluator, assessing their impact in terms of subjective wellbeing, and then looking for something better. We agree with GiveWell’s thinking that your donations will do more good if they’re used to fund interventions that help people living in extreme poverty. We’ve analysed three of those recommended interventions - cash transfers, deworming pills, and anti-malarial bednets - and compared them to treating depression in low-income countries. The whole process has taken three years. We’ve strived to assess the evidence as rigorously as possible and model our uncertainties in line with academic best practice.

We’re now in a position to confidently recommend StrongMinds as the most effective way we know of to help other people with your money. At the time of writing, StrongMinds is aiming to raise $20 million by 2025 to scale up their services and treat 150,000 people a year.

We’ll now go through the different analyses we’ve conducted to explain how we got here.

Cash transfers

A large number of academic studies show that cash transfers are a very effective way to reduce poverty. The strength of this evidence led GiveWell to recommend GiveDirectly as one of their top charities (from 2011 to 2022), and treat them as ‘the bar’ to beat.

But what impact do cash transfers have on subjective wellbeing? We conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate this question, bringing together 45 studies. We found that cash transfers have a small, long-lasting, and statistically significant positive effect on subjective wellbeing and mental health. This work was published in Nature Human Behaviour earlier this year.

Treating depression

But how does alleviating poverty compare to treating depression? I’ve long suspected that, if we focused on wellbeing, we might see that treating depression in low-income countries could be as, or more, cost-effective than providing cash transfers to those in extreme poverty. This was one of the main reasons I founded the Happier Lives Institute.

So, to enable an ‘apples-to-apples’ comparison to GiveWell’s recommendations, we needed to identify the most promising charities delivering mental health interventions in low-income countries. After a rigorous assessment of 76 mental health programmes, we identified StrongMinds as one of the best. It’s a non-profit that provides group interpersonal therapy for women in Uganda and Zambia who are struggling with depression.

Sean Mayberry, Founder and CEO of StrongMinds, is running an AMA (Ask Me Anything) on the Forum this week. If you have any questions about StrongMinds, please take this opportunity to ask him directly.

Cash transfers vs treating depression

To compare cash transfers to treating depression, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of group or lay-delivered psychotherapy in low-income countries, similar to the one we produced for cash transfers.

Drawing on evidence from over 80 studies and 140,000 participants, our cost-effectiveness analyses of cash transfers and psychotherapy allowed us to make a direct comparison between StrongMinds and GiveDirectly. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the cost-effectiveness of these two interventions has been compared in the same units using measures of subjective wellbeing.

To be clear, although both interventions are delivered in low-income countries, they are delivered to different groups of people. Only those diagnosed with depression are being treated for depression, whereas cash transfers are distributed to very poor people (only some of whom will be depressed).

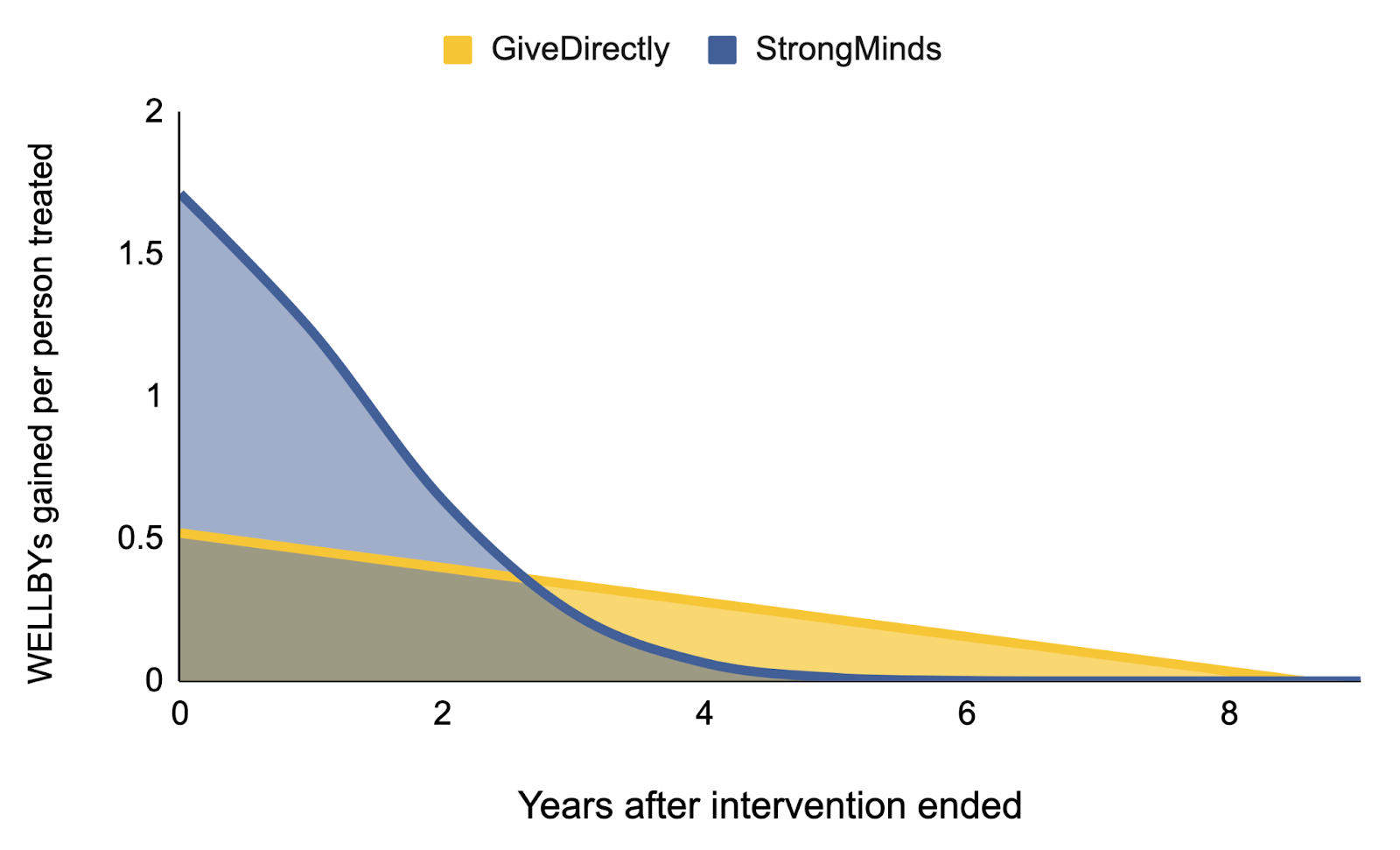

We illustrate the total effect of both interventions in Figure 1. StrongMinds’s group therapy has a similar overall effect to a $1,000 dollar cash transfer: the initial effect is larger, but it fades faster. What drives the difference is that group therapy costs much less ($170 per person).

Figure 1: Effects over time for GiveDirectly and StrongMinds

A few months later, we updated our analysis to include an estimate of the ‘spillover effects’ on other household members. For cash transfers, we estimate that each household member experiences 86% of the benefit received by the recipient. For psychotherapy, we estimate the spillover ratio to be 53%.

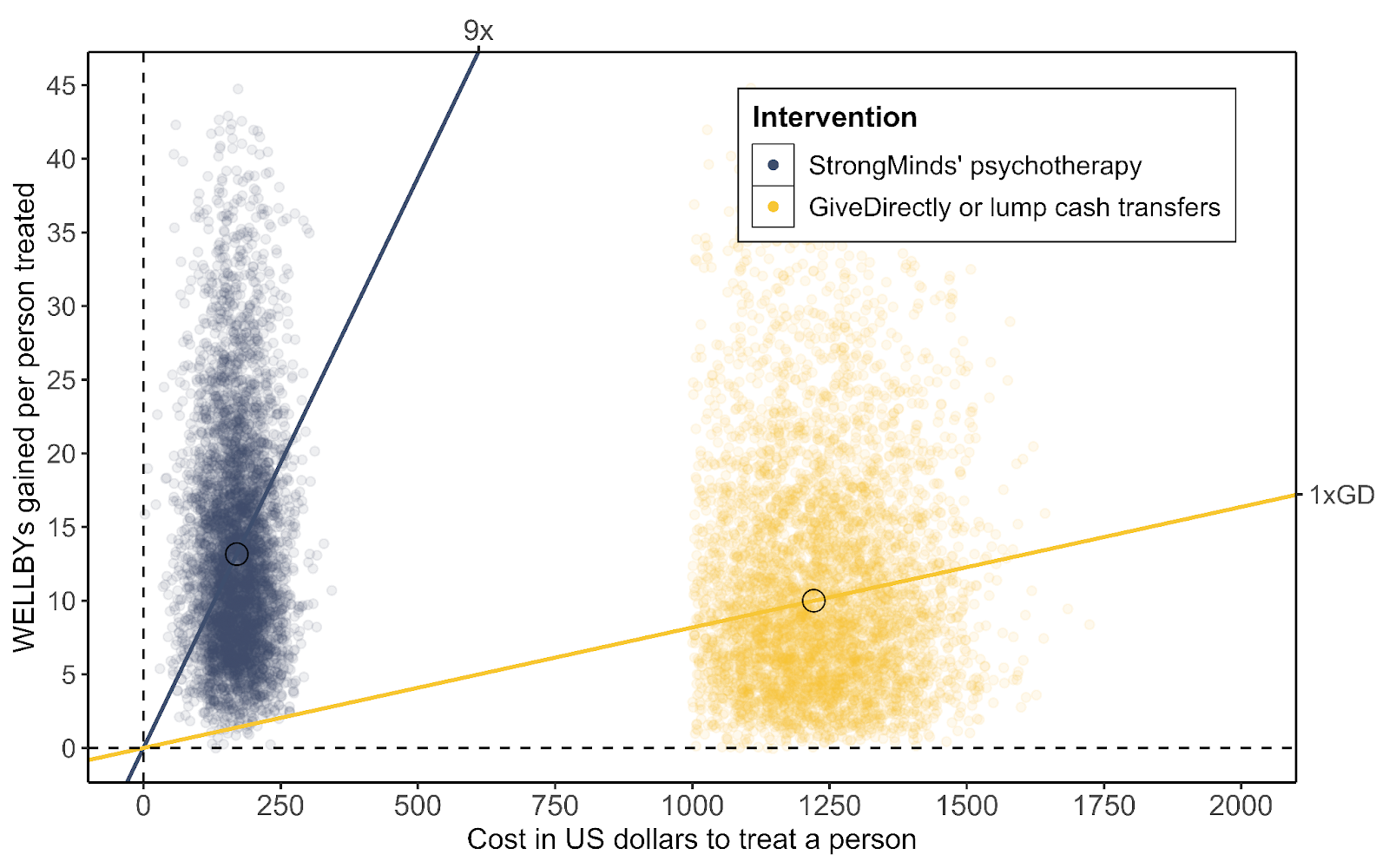

We also estimated the uncertainty in our model using a Monte Carlo simulation, where each dot represents a simulation. This is displayed below in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds compared to GiveDirectly

Overall, we estimate that StrongMinds is ~10 times more cost-effective than GiveDirectly. This finding presents a challenge to current thinking about the best ways to improve the lives of others and suggests that treating mental health conditions should be a much higher priority for donors and decision-makers.

Deworming

From 2011 until a few months ago, GiveWell recommended several deworming charities that treat large numbers of children for intestinal worms. The case for deworming is that it is very cheap (less than $1 per year of treatment per person) and there is suggestive evidence it might have large effects on later income (by improving educational outcomes which enable recipients to earn more in later life).

GiveWell has claimed that deworming programmes are several times more cost-effective than cash transfers. But how does deworming compare to treating depression, particularly when we look for the effects on happiness, not just income?

In July 2022, we published a critique of GiveWell’s deworming analysis. In replicating their model, we found an error in their calculations of the long-term income effects. With this correction, the total effects would be substantially smaller. In their response, GiveWell said:

Our current best guess is that incorporating decay into our cost-effectiveness estimates would reduce the cost-effectiveness of deworming charities by 10%-30%. This adjustment would have led to $2-$8 million less out of $55 million total to deworming since late 2019…We believe HLI’s feedback is likely to change some of our funding recommendations, at least marginally, and perhaps more importantly improve our decision-making across multiple interventions.

GiveWell subsequently launched their Change Our Mind Contest for which they awarded us a prize, retroactively. (Our follow-up entry to that contest suggested a dozen other problems with GiveWell’s analyses.)

In August 2022, GiveWell announced they had removed deworming charities from their top charities list. GiveWell now stipulates that their top charities must have “a high likelihood of substantial impact” and the evidence for deworming fails to meet that requirement.

Our analysis finds that deworming has a small, non-significant effect on happiness. Even if we take this non-significant effect at face value, deworming still looks about half as cost-effective as StrongMinds, with wide uncertainty.

In light of both our analysis and the fact that GiveWell has removed deworming from their list of top charities, we do not recommend any deworming charities over StrongMinds.

Life-extending charities

To complete our analysis of GiveWell’s top charities, we compared the relative value of life-improving and life-extending interventions. Our new report, The Elephant in the Bednet, explores this topic in detail.

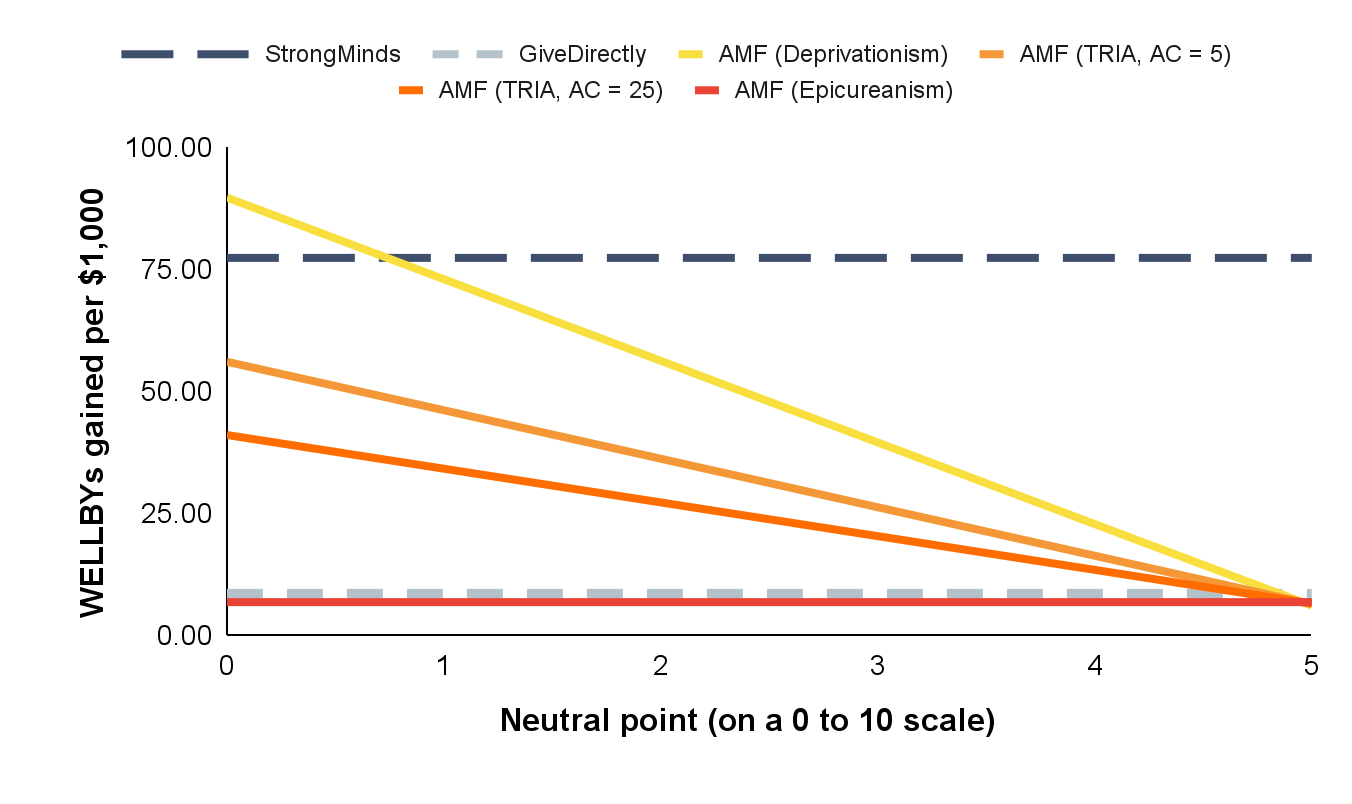

As the title suggests, this issue is important and unavoidable but it’s a question that people (understandably) find discomforting. The relative value of extending or improving life depends very heavily on your philosophical views about the badness of death and the point at which a person’s wellbeing changes from positive to negative (see Figure 3 below). Although these issues are well-known in academic philosophy, they are almost entirely glossed over by donors and decision-makers.

Figure 3: Cost-effectiveness of charities under different philosophical assumptions

The insecticide-treated nets distributed by the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF) have been considered a safe bet by the effective altruism community for many years: nets cost around $2 each and it costs, on average, a few thousand dollars to save a life. However, as you can see, the cost-effectiveness of AMF changes dramatically as we shift from one extreme of (reasonable) opinion to the other. In brief, the two crucial philosophical issues are: (a) determining the relative value of deaths at different ages, and (b) locating the neutral point on the wellbeing scale at which life is neither good nor bad for someone.

At one end, AMF is 1.3x better than StrongMinds. At the other, StrongMinds is 12x better than AMF. Ultimately, AMF is less cost-effective than StrongMinds under almost all assumptions.

Our general recommendation to donors is StrongMinds. We recognise that some donors will conclude that the Against Malaria Foundation does more good. It is not easy to explain the philosophical issues succinctly here so we advise interested individuals to read the full report to inform their decision-making.

We haven’t analysed them separately, but we expect effectively the same conclusions will apply to GiveWell’s other top charities which are recommended on the basis that they can prevent the deaths of very young children for between $3,500 and $5,000.These are:

- Helen Keller International (supplements to prevent vitamin A deficiency)

- Malaria Consortium (medicine to prevent malaria)

- New Incentives (cash incentives for routine childhood vaccines)

Mission accomplished

We have now completed Phase 1: we've (re)assessed GiveWell’s top charities using subjective wellbeing and compared their cost-effectiveness in terms of WELLBYs. We've shown that this can be done and found something better than the status quo: our recommended charity for 2022, StrongMinds.

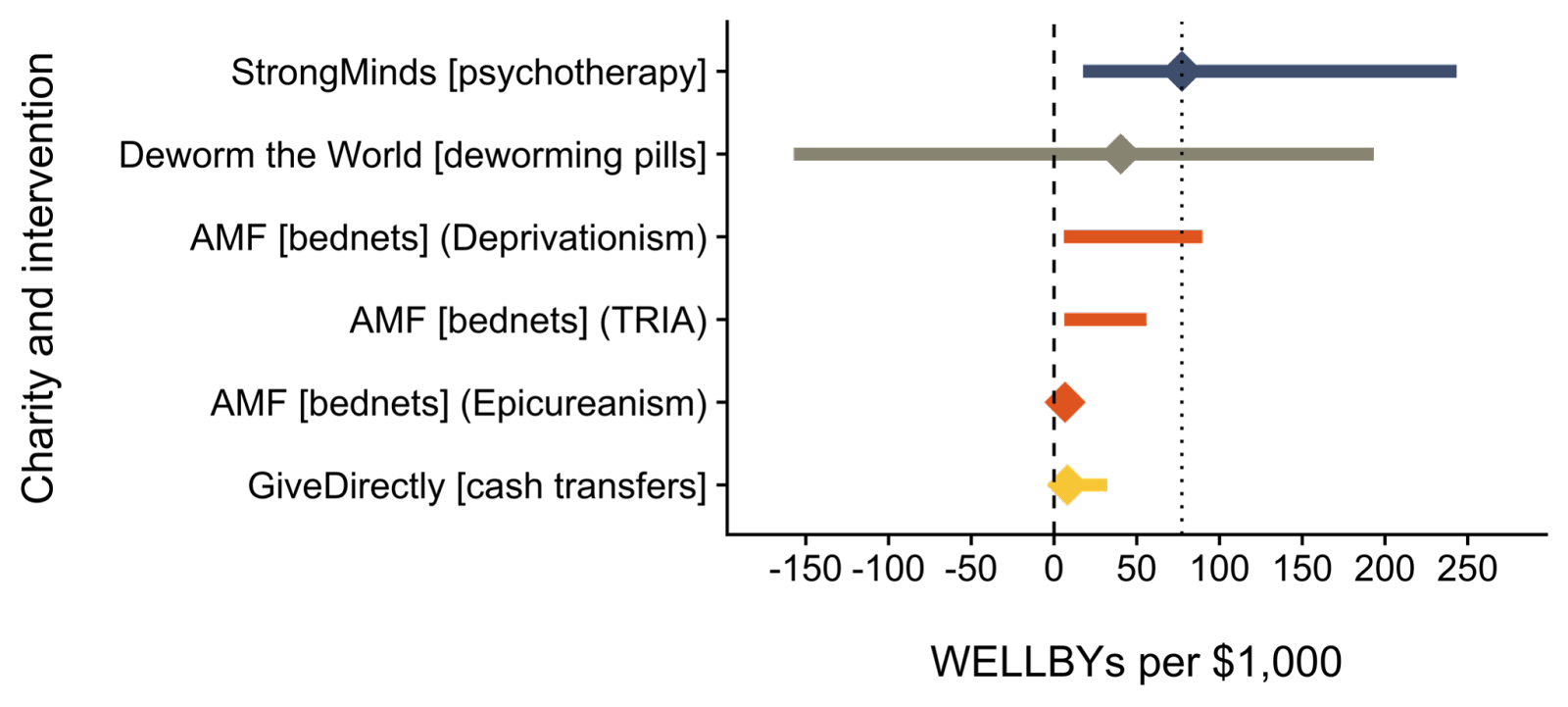

Our results are summarised in Figure 4, which represents three years of work in one chart!

Figure 4: Cost-effectiveness comparison forest plot

Notes:

- The diamonds represent the central estimate of cost-effectiveness.

- The solid whiskers represent the 95% confidence intervals for StrongMinds, Deworm the World, and GiveDirectly.

- The vertical dashed line represents 0 WELLBYs.

- The vertical dotted line is the point estimate of StrongMinds’ cost-effectiveness

- The lines for AMF are different from the others. They represent the upper and lower bound of cost-effectiveness for different philosophical views (not 95% confidence intervals). Think of them as representing moral uncertainty, rather than empirical uncertainty. The upper bound represents the assumptions most generous to extending lives and the lower bound represents those most generous to improving lives.

- The slogan version of the philosophical views are:

- Deprivationism: prioritise the youngest

- Time-relative interest account (TRIA): prioritise older children over infants.

- Epicureanism: prioritise living well, not living long

What’s next for HLI? On to Phase 2!

So far, we’ve looked at four ‘micro-interventions’, those where you help one person at a time. These were all in low-income countries. However, it’s highly unlikely that we’ve found the best ways to improve happiness already. Phase 2 is to expand our search.

We already have a pipeline of promising charities and interventions to analyse next year:

Charities we want to evaluate: CorStone (resilience training), Friendship Bench (psychotherapy), Lead Exposure Elimination Project (lead paint regulation), and Usona Institute (psychedelics research).

Interventions we want to evaluate: air pollution, child development, digital mental health, and surgery for cataracts and fistula repair.

We have a long list of charities and interventions that we won’t get to in 2023 but plan to examine in future years. Eventually, we plan to consider systemic interventions and policy reforms that could affect the wellbeing of larger populations at all income levels. There’s plenty to do!

Ready to give? Here’s how

If you’re convinced by our analysis, this section explains how to maximise the impact of your donation.

If you’re still on the fence, please ask questions in the comments section below or submit your question to Sean Mayberry, Founder and CEO of StrongMinds.

Double your donation (first chance)

From Tuesday 29 November, your donations to StrongMinds will be doubled if you donate through the 2022 Double Up Drive.

The matching starts at 8:00 am PT / 11:00 am ET / 4:00 pm GMT. We don’t know how big the matched pool will be or how long it will last so we advise you to donate as soon as it opens. Set a calendar reminder or an alarm now!

Double your donation (second chance)

If you miss the Double Up Drive, don’t panic! The UBS Optimus Foundation will also double your donation to StrongMinds until 31 December (up to a maximum of $800,000).

Make a tax-deductible donation

Once the two matching funds have run out, you can make a tax-deductible donation in the following countries: Australia, Canada, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States.

If your country is not listed above, you can make a direct donation at strongminds.org/donate

Support our further research

Our progress depends on the financial support of our donors and we are continuing to fundraise for our 2023 budget. If you’d like to see this research happen, please make a donation (donations are tax-deductible in the UK, the US, and the Netherlands).

DISCLAIMER: (perhaps a double edge sword) I've lived in Uganda here for 10 years working in Healthcare.

Thanks Michael for all your efforts. I love StrongMinds and am considering donating myself. I run health centers here in Northern Uganda and have thought about getting in touch with you see if we can use something like the Strong minds in the health centers we manage. While working as a doctor here my estimate from experience that for perhaps between 1 in 5 and 1 and 10 of our patients, depression or anxiety is the biggest medical problem in their lives. I feel bad every year that we do nothing at all to help these people.

Point 1

First I read a reply below that seriously doubted that improving depression could have more positive psychological effect than preventing the grief of the death of a child. On this front I think it's very hard to make a call in either direction, but it seems plausible to me that lifting someone out of depression could have a greater effect in many cases.

Point 2

I however strongly disagree with your statement here about self reporting. Sadly I think it is not a good measure especially as a primary outcome measure.

"Also, what's wrong with the self-reports? People are self-reporting how they feel. How else should we determine how people feel? Should we just ignore them and assume that we know best? Also, we're comparing self-reports to other self-reports, so it's unclear what bias we need to worry about."

Self reporting doesn't work because poor people here in Northern Uganda at least are primed to give low marks when reporting how they feel before an intervention, and then high marks afterwards - whether the intervention did anything or not. I have seen it personally here a number of times with fairly useless aid projects. I even asked people one time after a terrible farming training, whether they really thought the training helped as much as they had reported on the piece of paper. A couple of people laughed and said something like "No of course it didn't help, but if we give high grades we might get more and better help in future". this is an intelligent and rational response by recipients of aid, as of course good reports of an intervention increase their chances of getting more stuff in future, useful or not.

Dambisa Moyo says it even better in her book "Dead Aid", but couldn't find the quote. There might also be good research papers and other effective altruism posts that describe this failing of self reporting better than me so apologies if this is the case.

You also said "Also, we're comparing self-reports to other self-reports", which doesn't help the matter, because those who don't get help are likely to keep scoring the survey lowly because they feel like they didn't get help

Because of this I struggle to get behind any assessment that relies on self-reporting, especially in low income countries like Uganda where people are often reliant on aid, and desperate for more. Ironically perhaps I have exactly the same criticism of GiveDirectly. I think that researchers of GiveDirectly should use exclusively (or almost exclusively) objective measures of improved life (hemoglobin levels, kids school grades, weight for height charts, assets at home) rather the before and after surveys they do. To their credit, recent GiveDirectly research seem to be using more objective measures in their effectiveness research.

https://www.givedirectly.org/research-at-give-directly/

We can't ignore how people feel, but we need to try and find objective ways of assessing it, especially in contexts like here in Uganda where NGOs have wrecked any chance of self reporting being very accurate. I feel like measuring improvement in physical aspects of depression could be a way forward. Just off the top of my head you could measure before and after mental agility scores, which should improve as depression improves, or quality of sleep before and after using a smart watch or phone. Perhaps even you could use continuous body monitoring for a small number of people, as they did here

https://www.vs.inf.ethz.ch/edu/HS2011/CPS/papers/sung05_measures-depression.pdf

Alternatively I'd be VERY interested in a head to head Cash transfer vs Strongminds RCT - should be pretty straightforward , even potentially using your same subjective before and after scores. Surely this would answer some important questions.

A similar comparative RCT was done in Kenya in 2020 of cash transfer vs. Psychotherapy, and the cash transfers clearly came through on top https://www.nber.org/papers/w28106.

Anyway I think Strong minds is a great idea and probably works well to the point I really want to use it myself in our health centers, but I don't like the way you measure it's effectiveness and therefore doubt whether it is as effective as stated here.

Thanks for all the good work!

Hi Nick,

Thank you for sharing! This is valuable to hear. The issue of being primed to respond in a certain way has surprisingly not been explored widely in low-income countries.

We’re concerned about this, but to our knowledge, the existing evidence suggests this isn’t a large concern. The only study we’ve seen that explicitly tries to measure the impact of this was a module in Haushofer et al., (2020 section III.I) – where they find about a zero effect. If there’s more evidence we don’t know about, please share!

Here's the excerpt (they call these effects "experimenter demand effects").

Allow me to disagree -- I think this could help the matter when we're comparing between interventions. If this effect was substantial, the big concern would be if this effect differs dramatically between interventions. E.g., the priming effect is larger for psychotherapy than for cash transfers. I.e., it's okay if the same bias is balanced across interventions. Of course, I'm not sure if it's plausible for this to be the case -- my prior is pretty uniform here.

All that being said, I totally endorse more research on this topic!

I think this is probably a point where we disagree. A point we've expanded upon previously (see McGuire et al., 2022) is that we seriously doubt that we can measure feelings objectively. The only way we can know if that objective measure is capturing a feeling is by asking someone if it does so -- so why not just do that?

I am much more pro "find the flaws and fix them" then "abandon ship when it leaks" regarding measuring subjective wellbeing.

This may be in the works!

Thanks so much Joel and I’m stoked by your response. I don’t think I’ve been in a forum where discussion and analysis is this good.

I'm not sure that having close to no evidence on a major concern about potential validity of before and after surveys should be very reassuring.

That tiny piece of evidence you cited only looks at the “experimenter demand effect”, which is a concern yes, but not my biggest concern. My largest concern is let's say the “future hope” effect which I gave the example from in my first reply – where participants rate the effect of interventions more positively than their actual experience, because they CORRECTLY assess that a higher rating may bring them better help in future. That’s what I think is most likely to wreck these before and after surveys.

I don’t know this field well at all like you so yes it seems likely this is a poorly researched issue . We have experience and anecdotes like those from Dambisa Moyo, me and many others working in the NGO world, that these incentives and vested interests can greatly affect before and after surveys. You recently wrote an article which included (to your credit) 4 disadvantages of the WELLBY. My inclination is (with enormous uncertainty) that these problems I've outlined with before and after subjective surveys in low income countries are at least as big a disadvantage to the WELLBY approach as any of the 4 issues you outlined. I agree that SWB is a well validated tool for one time surveys and there are no serious vested interests involved. It’s the before and after surveys in low income countries that are problematic.

These are the 3 major un-accounted for problems I see with before and after self reporting (first 2 already discussed).

On the "Also, we're comparing self-reports to other self-reports" front - I agree this could be be fine if comparing between two interventions (e.g. cash and psychotherapy) and the effect might be similar between interventions. I think though most of the studies that you have listed compare intervention to no intervention, so your point may not stand in these cases.

I’ll change my mind somewhat in your direction and give you some benefit of the doubt on your point about objective measures not working well for wellbeing assessment, given that I haven’t researched it very well and I'm not an expert. Let's leave objective measures out of the discussion for the moment!

I love the idea of your RCT cash transfers vs. psychotherapy but I'm confused about a number of parts of the design and have a few questions if you will humour me .

- The study design seems to say you are giving cash only the intervention groups and not the control group? I suspect this is a mistake in the reporting of the study design but please clarify. To compare cash vs psychotherapy would you not give the cash to the whole control group and either not to the intervention group at all, or only a small subsection of the intervention group? I might well have missed something here...

- Why are you giving money at the end of the intervention rather than at the start? Does that not give less time for the benefits of the cash to take effect.

- Why are you only giving $50 cash transfer and not around $130 (the cost of the therapy). Would it not would be a fairer comparison to compare like for like in terms of money spent on the intervention?

It seems logical that most RCTs in the effective altruism space now should be intervention vs cash transfer, or at least having 3 arms Intervention vs cash transfer vs nothing. Hopefully I've read it wrong and that is the case in this study!

To finish I like positivity and I'll get alongside your point about fixing the boat rather than dismissing it. I feel like the boat is more than a little leak at this stage, but I hope I'm wrong I love the idea of using before and after subjective wellness measures to assess effectiveness of interventions, I'm just not yet convinced yet it can give very meaningful results based on my issues above.

Thanks so much if you got this far and sorry it's so long!

A quick response -- I'll respond in more depth later,

To be clear, the planned RCT has nothing to do with HLI, so I would forward all questions to the authors! :)

And to be clear when you say "before and after measures", do you think this applies to RCTs where the measurement of an effect is comparing a control to a treatment group instead of before and after a group receives an intervention?

Apologies for assuming that the RCT involved HLI - the strong minds involvement lead me to that wrong assumption! They will then be addressing different questions than we are here - unfortunately for us that trial as stated in the protocol doesn't test cash transfers vs. psychotherapy.

I don't quite understand the distinction in your question sorry, will need rephrasing! I'm referencing the problems with any SWB measurement which involves measuring SWB at baseline and then after an intervention. Whether there is a control arm or not.

Looking forward to hearing more nice one!

Right, our concern is that if this bias exists, it is stronger for one intervention than another. E.g., say psychotherapy is more susceptible than cash transfers. If the bias is balanced across both interventions, then again, not as much of an issue.

I'm wondering if this bias your concerned with would be captured by a "placebo" arm of an RCT. Imagine a control group that receives an intervention that we think has no to little effect. If you expect any intervention to activate this "future hope" bias, then we could potentially estimate the extent of this bias with more trials including three arms: a placebo, a receive nothing, and an intervention arm.

Do you have any ideas on how to elicit this bias experimentally? Could we instruct interviewers to, for a subsample of the people in a trial, explicit something like "any future assistance [ will / will not] depend on the benefit this intervention provided." Anything verbal like this would be cheapest to test.

Hi Joel - Nice one again

"Right, our concern is that if this bias exists, it is stronger for one intervention than another. E.g., say psychotherapy is more susceptible than cash transfers. If the bias is balanced across both interventions, then again, not as much of an issue."

I would have thought the major concern would have been if the bias existed at all, rather than whether it balanced between interventions. Both StrongMinds evidence assessing their own program and most of the studies used in your WELLBY analysis are NOT vs. another intervention, but rather Psychotherapy vs. No intervention. This is often labelled "Normal care", which is usually nothing in low income countries. So if it exists at all in any magnitude, it will be affecting your results.

Onto your question though, which is still important but I believe of secondary importance

Your idea of a kind of "fake" placebo arm would work - providing the fake placebo was hyped up as much and taken as seriously as the treatment arm, AND that the study participants really didn't know it was a placebo. Unfortunately you can't do this as It's not ethical to have an RCT with an intervention that you think has no or little effect. So not possible I don't think

I like your idea of interviewers in a trial stating for a subset of people that their answers won't change whether they get more or not n future. I doubt this would mitgate the effect much or at all, but it's a good idea to try!

My very strong instinct is that cash transfers would illicit a FAR stronger effect than psychotherapy. It's hard to imagine anything that would illicit "future hope" more than the possibility of getting cash in future. This seems almost self-evident. Which extremely poor person in their right mind (whether their mental health really is better or not) is going to say that cash didn't help their mental health if they think it might increase their chance of getting more cash in future?

Again I think just direct RCTs vs. Cash Transfers is the best way to test your intervention and control for this bias. It's hard to imagine anything having a larger "future hope" effect than cash. If psychotherapy really beat the cash given that cash will almost certainly have a bigger "future hope" bias than the psychotherapy, then I'd say you'd have a slam dunk case.

I am a bit bewildered that StrongMinds has never done a psychotherapy vs. Cash transfer trial. This is the big question, and you claim that Strongminds therapy produces more WELLBYs than Cash Transfers yet there is no RCT? It looks like that trial you sent me is another painful missed opportunity to do that research as well. Why there is no straight cash transfer arm in that trial doesn't make any sense.

As far as I can see the Kenyan trial is the only RCT with Subjective wellness assessment which pits Cash Transfers vs. Psychotherapy (although it was a disproportionately large cash transfer and not the Strongminds style group therapy). If group Psychotherapy beat an equivalent cash Cash transfer in say 2 RCTs I might give up my job and start running group psychotherapy sessions - that would be powerful!

Hi Nick. I found more details about the Baird et al. RCT here. I've copied the section about the 'cash alone' arm below as I know you'll be interested to read that:

Thanks Barry I tried to find this earlier but couldn't.

I find these arguments rather uncompelling. What do you think Barry and Joel? (I wish I could tag people on this forum haha)

That they feel the need to write 4 paragraphs to defend against this elephant in the room says a lot. The question we are all still asking is how much better (if at all) StrongMinds really is than cash for wellbeing.

My first question is why don't they reference the 2020 Haushofer study, the only RCT comparing psychotherapy to cash and showing cash is better? https://www.nber.org/papers/w28106

Second, their equipoise argument is very poor. The control arm should have been BRAC ELA club + cash. Then you keep 3 arms and avoid their straw man 4 arm problem. You would lose nothing in equipoise giving cash to the control arm - I don't understand the equipoise argument perhaps I'm missing something?

Then third there's this...

"Should the trial show that IPT-G+ is significantly more effective than IPT-G alone in reducing depression in the medium-run, our interpretation will be that there is a complementarity between the two interventions, and not that cash is effective on its own for sustained improvements in psychological wellbeing."

This is the most telling paragraph. It's like, we designed our study so that even if we see that cash gives a big boost, we aren't going to consider the alternative that we don't like. It seems to me like they are defending poor design post-hoc, rather than that they made good decision made in advance.

The more I see this, the more I suspect that leaving the cash arm out was either a big mistake or an intentional move by the NGOs. What we have now is a million dollar RCT, which doesn't answer conclusively the most important question we are all asking. This leaves organisations like your HLI having to use substandard data to assess psychotherapy vs. cash because there is no direct gold standard comparison.

It's pretty sad that a million dollars will be spent on a study that at best fails to address the elephant in the room (while spending 4 paragraphs explaining why they are not). Other than that the design and reasoning in this study seems fantastic.

Hey Nick, thanks for this very valuable experience-informed comment. I'm curious what you make of the original 2002 RCT that first tested IPT-G in Uganda. When we (at Founders Pledge) looked at StrongMinds (which we currently recommend, in large part on the back of HLI's research), I was surprised to see that the results from the original RCT lined up closely with the pre/post scores reported by recent program participants.

Would your take on this result be that participants in the treated group were still basically giving what they saw as socially desirable answers, irrespective of the efficacy of the intervention? It's true that the control arm in the 2002 RCT did not receive a comparable placebo treatment, so that does seem a reasonable criticism. But if the socially desirability bias is so strong as to account for the massive effect size reported in the 2002 paper, I'd expect it to appear in the NBER paper you cite, which also featured a pure control group. But that paper seems to find no effect of psychotherapy alone.

Matt these are fantastic questions that I definitely don't have great answers to, but here are a few thoughts.

First I'm not saying at all that the Strong minds intervention is likely useless - I think it is likely very useful. Just that the positive effects may well be grossly overstated for the reasons outlined above.

My take on the result of that original 2002 RCT and Strong Minds. Yes like you say in both cases it could well be that the treatment group are giving positive answers both to appease the interviewer (Incredibly the before and after interviews were done by the same researcher in that study which is deeply problematic!) and because they may have been hoping positive responses might provide them with further future help.

Also in most of these studies, participants are given something physical for being part of the intervention groups. Perhaps small allowances for completing interviews, or tea and biscuits during the sessions. These tiny physical incentives can be more appreciated than the actual intervention. Knowing World Vision this would almost certainly be the case

I have an immense mistrust of World vision for a whole range of reasons, who were heavily involved in that famous 2002 RCT. This is due to their misleading advertising and a number of shocking experiences of their work here in Northern Uganda which I won't expand on. I even wrote a blog about this a few years ago, encouraging people not to give them money. I know this may be a poor reason to mistrust a study but my previous experience heavily biases me all the same.

Great point about the NBER paper which featured a pure control group. First it was a different intervention - individual CBT not group therapy.

Second it feels like the Kenyan study was more dispassionate than some of the other big ones. I might be wrong but a bunch of the other RCTs are partly led and operated by organisations with something to prove. I did like that the Kenyan RCT felt less likely to be biased as there didn't seem to be as much of an agenda as with some other studies.

Third, the Kenyan study didn't pre-select people with depression, the intervention was performed on people randomly selected from the population. Obviously this means you are comparing different situations when comparing this to the studies with group psychotherapy for people with depression.

Finally allow me to speculate with enormous uncertainty. I suspect having the huge 1000 dollar cash transfers involved really changed the game here. ALL participants would have known for sure that some people people were getting the cash and this would have changed dynamics a lot. One outcome could have been that other people getting a wad of cash might have devalued the psychotherapy in participants eyes. Smart participants may even have decided the were more likely to get cash in future if they played down the effect of the therapy. Or even more extreme the confounding could go in the opposite direction of other studies, if participants assigned to psychotherapy undervalued a potentially positive intervention, out of disappointment at not getting the cash in hand. Again really just summising, but never underrate the connectivity and intelligence of people in villages in ths region!

Thanks for the post Michael — these sorts of posts have been very helpful for making me a more informed donor. I just want to point out one minor thing though.

I appreciate you and your team's work and plan on donating part of my giving season donations to either your organisation, Strongminds, or a combination of both. But I did find the title of this post a bit unnecessarily adversarial to GiveWell (although it's clever, I must admit).

I've admired the fruitful, polite, and productive interactions between GW and HLI in the past and therefore I somewhat dislike the tone struck here.

Thanks for the feedback Julian. I've changed the title and added a 'just' that was supposed to have been added to final version but somehow got lost when we copied the text across. I don't know how much that mollifies you...

We really ummed and erred about the title. We concluded that it was cheeky, but not unnecessarily adversarial. Ultimately, it does encapsulate the message we want to convey: that we should compare charities by their overall impact on wellbeing, which is what we think the WELLBY captures.

I don’t think many people really understand how GiveWell compares charities, they just trust GiveWell because that’s what other people seem to do. HLI’s whole vibe is that, if we think hard about what matters, and how we measure that, we can find even more impactful opportunities. We think that’s exactly what we’ve been able to do - the, admittedly kinda lame, slogan we sometimes use is ‘doing good better by measuring good better’.

To press the point, I wouldn’t even know how to calculate the cost-effectiveness of StrongMinds on GiveWell’s framework. It has two inputs: (1) income and (2) additional years of life. Is treating depression good just because it makes you richer? Because it helps you life longer? That really seems to miss the point. Hence, the WELLBY.

Unless GiveWell adopt the WELLBY, we will inevitably be competing with them to some extent. The question is not whether we compete - the only way we could not compete would be by shutting down - it's how best to do it. Needless antagonism is obviously bad. We plan to poke and prod GiveWell in a professional and humourful way when we think they could do better - something we’ve been doing for several years already - and we hope they'll do the same to us. Increased competition in the charity evaluation space will be better for everyone (see GWWC’s recent post).

I didn't see the old title, but FWIW I had the same thought as Julian had about the old title about this title when I saw it just now:

"give well" clearly seemed like a reference to GiveWell to me. It sounded like you're saying "Don't give according to GiveWell's recommendations; give according to HLI's recommendations made on the basis of maximizing WELLBYs."

It's perfectly fine to say this of course, but I think it's a bit off-putting to say it subtly like that rather than directly. Also it seems strange to make that statement the title, since the post doesn't seem to be centrally about that claim.

I personally think it's a good enough pun to be worth the cost (and I do think there is still a real, albeit I think somewhat minor, cost paid in it feeling a bit adversarial). I've laughed about it multiple times today as I revisited the EA Forum frontpage, and it lightened up my day a bit in these somewhat stressful times.

Fair enough. I agree that the current title feeling a bit adversarial is only a minor cost.

I've realized that my main reason for not liking the title is that the post doesn't address my concerns about the WELLBY approach, so I don't feel like the post justifies the title's recommendation to "give WELLBYs" rather than "give well" (whether that means GiveWell or give well on some other basis).

On a meta-note, I'm reluctant to down-vote Julian's top comment (I certainly wouldn't want it to have negative karma), but it is a bit annoying that the (now-lengthy) top comment thread is about the title rather than the actual post. I suppose I'm mostly to blame for that by replying with an additional comment (now two) to the thread, but I also don't want to be discouraged from adding my thoughts just by the fact that the comment thread is highly upvoted and thus prominently visible. (I strong-agreement-voted Julian's comment, and refrained from regular karma voting on it.)

That phrasing is better, IMO. Thanks Michael.

I think the debate between HLI and GW is great. I've certainly learned a lot, and have slightly updated my views about where I should give. I agree that competition between charities (and charity evaluators) is something to strive for, and I hope HLI keeps challenging GiveWell in this regard.

TL;DR: This post didn't address my concerns related to using WELLBYs as the primary measurement of how much an intervention increases subjective wellbeing in the short term, so in this comment I explain my reasons for being skeptical of using WELLBYs as the primary way to measure how much an intervention increases actual wellbeing.

~~~~

In Chapter 9 ("Will the Future Be Good or Bad?") of What We Owe the Future, Will MacAskill briefly discusses life satisfaction surveys and raises some points that make me very skeptical of HLI's approach of using WELLBYs to evaluate charity cost-effectiveness, even from a very-short-term-ist hedonic utilitarian perspective.

Here's an excerpt from page 196 of WWOTF, with emphasis added by me:

Some context on the relative value of different conscious experiences:

Most people I have talked to think that the negative wellbeing experiences they have had tend to be much worse than their positive wellbeing experiences are good.

In addition to thinking this about typical negative experiences compared to typical positive experiences, most people I talk to also seem to think that the worst experience of their life was several times more bad than their best experience was good.

People I talk to seem to disagree significantly on how much better their best experiences are compared to their typical positive experience (again by "better" I mean only taking into account their own wellbeing, i.e. the value of their conscious experience). Some people I have asked say their best day was maybe only about twice as good as their typical (positive) day, others think their best day (or at least best hour or best few minutes) are many times better (e.g. ~10-100 times better) than their typical good day (or other unit of time).

In the Effective Altruism Facebook group 2016 poll "How many days of bliss to compensate for 1 day of lava-drowning?" (also see 2020 version here), we can see that EAs' beliefs about the relative value of the best possible experience and the worst possible experience span many orders of magnitude. (Actually, answers spaned all orders of magnitude, including "no amount of bliss could compensate" and one person saying that even lava-burning is positive value.)

Given the above context, why 0-10 measures can't be taken literally...

It seems to me that 0-10 measures taken from subjective wellbeing / life satisfaction surveys clearly cannot be taken literally.

That is, survey respondents are not answering on a linear scale. An improvement from 4 to 5 is not that same as an improvement from 5 to 6.

Respondents' reports are not comparable to each others'. One person's 3 may be better than another's 7. One person's 6 may be below neutral wellbeing, another person's 2 may be above neutral wellbeing.

The vast majority of respondents' answers presumably are not even self-consistent either. A "5" report one day is not the same as a "5" report a different day, even for the same person.

If the neutral wellbeing point is indeed around 1-2 for most people answering the survey, and peoples' worst experiences are much worse than their best experiences are good (as many people I've talked to have told me), then such surveys clearly fail to capture that improving someone's worst day to a neutral wellbeing today is much better than making someone's 2 day into a 10 day. That is, it's not the case that an improvement from 2 to 10 is five times better than an improvement from 0 to 2 in many cases, as a WELLBY measurement would suggest. In fact, the opposite may be true (with the improvement from 0 to 2 (or whatever neutral wellbeing is) potentially being 5 times greater (or even more times greater) than an improvement from 2 to 10. This is a huge discrepancy and I think gives reason to think that using WELLBY's as the primary tool to evaluate how much interventions increase wellbeing is going to be extremely misleading in many cases.

What I'm hearing from you

I see:

As a layperson note that I don't know what this means.

(My guess (if it's helpful to you to know, e.g. to improve your future communications to laypeople) is that the "scientifically valid" means something like "if we run an RTC in which we give a control group a subjective wellbeing survey and another group that we're doing some intervention on to make them happier the same survey, we find that the people who are happier give higher numbers on the survey. Then later when we run this study again, we find consistent results with people giving higher scores in approximately the same range for the same intervention, which we interpret to mean that the self-reported wellbeing is actually a measurement of something real.)

Despite not being sure what it means for the surveys to be scientifically valid, I do know that I'm struggling to think of what it could mean such that it would overcome my concerns above about using subjective wellbeing surveys as the main measure of how much an intervention improves wellbeing.

Peoples' 0-10 subjective wellbeing reports seem like they are somewhat informative about actual subjective wellbeing—e.g. given only information about two people's self-reported subjective wellbeing I'd expect the wellbeing of the person with the higher reported wellbeing to be higher—but there are a host of reasons to think that 1-point increases in self-reported wellbeing don't correspond to actual wellbeing being increased by some consistent amount (e.g. 1 util) and reading this post didn't give me reason to think otherwise.

So I still think a cost-effectiveness analysis that uses subjective wellbeing assessments as more than just one small piece of evidence seems very likely to fail to identify what interventions actually increase subjective wellbeing the most. I'd be interested in reading a post from HLI that advocates for their WELLBYs approach in light of the sort of the concerns mentioned above.

Hello William, thanks for this. I’ve been scratching my head about how best to respond to the concerns you raise.

First, your TL;DR is that this post doesn’t address your concerns about the WELLBY. That’s understandable, not least because that was never the purpose of this post. Here, we aimed to set out our charity recommendations and give a non-technical overview of our work, not get into methodological and technical issues. If you want to know more about the WELLBY approach, I would send you to this recent post instead, where we talk about the method overall, including concerns about neutrality, linearity, and comparability.

Second, on scientific validity, it means that your measure successfully captures what you set out to measure. See e.g. Alexandrova and Haybron (2022) on the concept of validity and its application to wellbeing measures. I'm not going to give you chapter and verse on this.

Regarding linearity and comparability, you’re right that people *could* be using this in different ways. But, are they? and would it matter if they did? You always get measurement error, whatever you do. An initial response is to point out that if differences are random, they will wash out as ‘noise’. Further, even if something is slightly biased, that wouldn't make it useless - a bent measuring stick might be better than nothing. The scales don’t need to be literally exactly linear and comparable to be informative. I’ve looked into this issue previously, as have some others, and at HLI we plan to do more on it: again, see this post. I’m not incredibly worried about these things. Some quick evidence. If you look at map of global life satisfaction, it’s pretty clear there’s a shared scale in general. It would be an issue if e.g. Iraq gave themselves 9/10.

Equally, it's pretty clear that people can and do use words and numbers in a meaningful and comparable way.

In your MacAskill quotation, MacAskill is attacking a straw man. When people say something is, e.g. "the best", we don't mean the best it is logically possible to be. That wouldn't be helpful. We mean something more like the "the best that's actually possible", i.e. possible in the real world. That's how we make language meaningful. But yes, in another recent report, we stress that we need more work on understanding the neutral point.

Finally, and the thing I think you've really missed about all this, is that: if we're not going to use subjective wellbeing surveys to find out how well or badly people's lives are going, what are we going to use instead? Indeed, MacAskill himself says in the same chapter you quote from of What We Owe The Future:

Thank you very much for taking the time to write this detailed reply, Michael! I haven't read the To WELLBY or not to WELLBY? post, but definitely want to check that out to understand this all better.

I also want to apologize for my language sounding overly critical/harsh in my previous comment. E.g. Making my first sentence "This post didn't address my concerns related to using WELLBYs..." when I knew full well that wasn't what the post was intending to address was very unfair of me.

I know you've put a lot of work into researching the WELLBY approach and are no doubt advancing our frontier of knowledge of how to do good effectively in the process, so I want to acknowledge that I appreciate what you do regardless of any level of skepticism I may still have related to heavily relying on WELLBY measurements as the best way to evaluate impact.

As a final note, I want to clarify that while my previous comment may have made it sound like I was confident that the WELLBY approach was no good, in fact my tone was more reflective of my (low-information) intuitive independent impression, not my all-things-considered view. I think there's a significant chance that when I read into your research on neutrality, linearity, and comparability, etc, that I'll update toward thinking that the WELLBY approach makes considerably more sense than I initially assumed.

Hello William,

Thanks for saying that. Yeah, I couldn't really understand where you were coming from (and honestly ended up spending 2+ hours drafting a reply).

On reflection, we should probably have done more WELLBY-related referencing in the post, but we were trying to keep the academic side light. In fact, we probably need to recombine our various scratching on the WELLBY and put them onto a single page on our website - it's been a lower priority than doing the object-level charity analysis work.

If you're doing the independent impression thing again, then, as a recipient, it would have been really helpful to know that. Then I would have read it more as a friendly "I'm new to this and sceptical and X and Y - what's going on with those?" and less as a "I'm sceptical, you clearly have no idea what you're talking about" (which was more-or-less how I initially interpreted it... :) )

Ah, I'm really sorry I didn't clarify this!

For the record, you're clearly an expert on WELLBYs and I'm quite new to thinking about them.

My initial exposure to HLI's WELLBY approach to evaluating interventions was the post Measuring Good Better and this post is only my second time reading about WELLBYs. I also know very little about subjective wellbeing surveys. I've been asked to report my subjective wellbeing on surveys before, but I've basically never read about them before besides that chapter of WWOTF.

The rest of this comment is me offering an explanation on what I think happened here:

Scott Alexander has a post called Socratic Grilling that I think offers useful insight into our exchange. In particular, while I absolutely could and should have written my initial comment to be a lot friendlier, I think my comment was essentially an all-at-once example of Socratic grilling (me being the student and you being the teacher). As Scott points out, there's a known issue with this:

Later:

When I first read about HLI's approach in the Measuring Good Better article my reaction was "Huh, this seems like a poor way to evaluate impact given [all the aspects of subjective wellbeing surveys that intuitively seemed problematic to me]."

If I was talking with you in person about it I probably would have done a back-and-forth Socratic grilling with you about it. But I didn't comment. I then got to this post some weeks later and was hoping it would provide some answer to my concerns, was disappointed that that was not the post's purpose, and proceeded to write a long post explaining all my concerns with the WELLBY approach so that you or someone could address them. In short, I dumped a lot of work on you and completely failed to think about how (Scott's words:) " it would sound like the student was challenging the teacher," and how I could come across as an "arrogant know-it-all who thinks he’s checkmated" you, and how "Tolerating this is harder than it sounds".

So I'm really sorry about that and will make it a point to make sure I actually think about how my comments will be received next time I'm tempted to "Socratically grill" someone, that way I can make sure my comment comes across as friendly.

Thanks for this post, fascinating stuff!

My quick-ish question: is it possible that you are underestimating the WELLBY effect of grief, for AMF? My understanding (from referring back to the 'elephant in the bednet' post, but totally possible that I've missed something) is that these estimates are coming from Oswald and Powdthavee (2008), and then assuming a 5 year duration from Clark et al. (2018). Hence getting an estimate of ~ 7 WELLBYs.

The reason I'm a little skeptical of this is first that it seems likely to me (disclaimer that I have not done a deep dive) that losing a child would increase the likelihood of depression and other mental illnesses, alongside other things like marriage disruption (e.g. Rogers et al. 2008, which highlights effects lasting to the 18 year mark). I don't think these effects will be accounted for by pulling out the estimate coming from Oswald & Powdthavee according to the Clark paper.

Along similar lines, I also think the spillover effects of AMF might be underestimated; my intuition is that losing a child is inherently especially shocking, and that the spillover effects might larger than the spillover effects from things like cash transfers/ therapy- e.g. everyone in the community feels sad (to some degree) about it. Am I correct that the spillover for AMF is calculated only for family members, not for friends and other members of the community?

Hi Rosie,

Thanks for your comment! Grief is a thorny issue, and we have different priors about it as a team.

Could you clarify why you think the effects aren't accounted for? Is it because we aren't specifically looking at evidence that captures the long-term effects of grief for the loss of a child?

If so I'm not sure that child-loss will have a different temporal dynamic than spouse-loss. I'd assume that spouse-loss, if anything, would persist longer. However, this was a shallow estimate that could be improved upon with more research -- but we haven't prioritized further research because we don't expect it to make much of a difference.

Rather than underestimate grief, I'm inclined to think our grief estimate is relatively generous for several reasons.

All of this being said, I don't think it would change our priorities even if we had a sizeable change to the grief numbers, eg doubled or halved them, so we aren't sure how much effort it's worth to do more work.

Hi Joel, thanks for this detailed + helpful response! To put in context for anyone skimming comments, I found this report fascinating, and I personally think StrongMinds are awesome (and plan to donate there myself).

Yep, my primary concern is that I'm not sure the longterm effects of grief from the loss of a child have been accounted for. I don't have access to the Clark book that I think the 5 year estimate comes from- maybe there is really strong evidence here supporting the 5 year mark (are they estimating for spouse loss in particular?). But 5 years for child loss intuitively seems wrong to me, for a few reasons:

I do realise there may be confounding variables in the analyses above (aka so they're overestimating grief as a result)- this might be where i'm mistaken. However, this does fit with my general sense that people tend to view the death of a child as being *especially* bad.

My secondary concern is that I think the spillover effects here might go considerably beyond immediate household members. In response to your points;

I do want to highlight the potential 'duration of effect' plus 'negative spillover might be higher than (positive) spillover effects from GD' issues because I think those might change the numbers around a fair bit. I.e. if we assume that effects last 10 years rather than 5 (and I see an argument that child bereavement could be like 20+) , and spillover is maybe 1.5X as big as assumed here, that would presumably make AMF 3X as good.

This is great to hear! I'm personally more excited by quality-of-life improvement interventions rather than saving lives so really grateful for this work.

Echoing kokotajlod's question for GiveWell's recommendations, do you have a sense of whether your recommendations change with a very high discount rate (e.g. 10%)? Looking at the graph of GiveDirectly vs StrongMinds it looks like the vast majority of benefits are in the first ~4 years

Minor note: the link at the top of the page is broken (I think the 11/23 in the URL needs to be changed to 11/24)Do you mean a pure time discount rate, or something else?

I think a pure-time discount rate would actually boost the case for StrongMinds, right? Regarding cash vs therapy, the benefits from therapy happen more so at the start. Regarding saving lives vs improving lives, the benefit of a saved life presumably applies over the many extra years the person lives for.

I feel very uncomfortable mutiplying, dividing adding up these wellbys as if they are interchangeable numbers.

I have skimmed this - but if I'm reading the graph right... you believe therapy generates something like 3 wellbys of benefit per attendee?

And you say in your elephant bednet report "We estimate the grief-averting effect of preventing a death is 7 WELLBYs for each death prevented"

So a person attending therapy is roughly equivalent to preventing one parent's grief at death of a child?

This doesn't seem plausible to me.

Apologies if I have misunderstood somewhere.

Yeah, it is a bit weird, but you get used to it! No weirder than using QALYs, DALYs etc. which people have been doing for 30+ years.

Re grief, here's what we say in section A.2 of the other report

I'm not sure what you find weird about those numbers.

As described elsewhere, the approach of measuring happiness/sentiment in a cardinal way and comparing this to welfare from pivotal/tragic life events measured in years/disability, seems challenging and the parent comment's concerns about the magnitudes seems dubious is justified.

GHD is basically built on a 70-year graveyard of very smart people essentially doing meta things that don't work well.

Some concerns that an educated reasonable person should raise (and have been raised are)

The above aren't dispositive, but the construct of WELLBY does not at all seem easy to compare to QALYs and DALYs, and the pat response is unpromising.

Can you elaborate a little bit about Stronger Minds claiming they almost literally solve depression? That would be a pretty strong claim, considering how treatment resistant depression can be.

I suppose I would be open to the idea that in Western countries we are treating the long tail of very treatment resistant depression whereas in developed countries, there are many people who get very very little of any kind of care and just a bit of therapy makes a big difference.

In this other thread, see this claim.

This phrasing is a yellow flag to me, it's a remarkably large effect, without contextualizing it in a specific, medical claim (e.g. so it can be retreated from).The description of the therapy itself is not very promising. https://strongminds.org/our-model/

This is a coarse description. It does not suggest how such a powerful technique is reliably replicated and distributed.

Strong Minds appears to orchestrate its own evaluations, controlling data flow by local hiring contractors.

I'll be honest - personally I'm not convinced by the StrongMinds recommendation. And it all goes back to my earlier post arguing we should be researching better interventions rather than funding current ones. I was pleased to see further research on this point here and here, both of which HLI employee Joel McGuire contributed to (although in a personal capacity not related to HLI), and both of which were positive about further research.

Just imagine how much better we can do than group talk therapy. We can probably develop psychedelics / treatments to completely eradicate depression and make us all blissful all the time. Sure, it might take some time, but it will be worth it, and we'll certainly get some benefits along the way.

Relying on WELLBYs means relying on interventions we already know about. But we can do so much better than this. Consider that mental health problems used to be treated by drilling holes in people's skulls. What if we had stopped researching at that point?

I think we're missing a lot of potential value here.

We plan to evaluate Usona Institute next year. We still need to raise $300k to cover our 2023 budget if you prefer to fund further research over direct interventions.

Sorry I clearly hadn't read the post closely enough. I had seen:

And read this as you planning to continue evaluating everything in WELLBYs, which in turn I thought meant ruling out evaluating research - because it isn't clear to me how you evaluate something like psychedelics research using WELLBYs.

Do you have any idea how you would methodologically evaluate something like Usona?

Hi Jack,

I'll try and give a general answer to your concern. I hope this helps?

Whilst there might be some aspects of research that can be evaluated without looking at WELLBYs (e.g., how costly is psychedelics treatment), the core point is still that wellbeing is what matters. More research will tell us that something is worth it if it does 'good'; namely, it increases WELLBYs (cost-effectively).

We hope to obtain wellbeing data (life satisfaction, affect, etc.) for each area we evaluate. If it is lacking, then we hope to encourage more data collection and / or to evaluate pathways (e.g., if psychedelics affect variable X, do we know the relationship between X and wellbeing).

Thanks Samuel.

The point I’m trying to make is that it’s impossible to collect data on interventions that don’t yet exist. We might be able to estimate the impact of current psychedelics on well-being, but it is going to be a lot more difficult to estimate the impact that psychedelics will have on well-being in say five years time if we fund loads of research into making them better.

As such I think a novel approach may be required to evaluate something like Usona. There might still be a WELLBY approach suitable but I suspect it would have to be expected WELLBYs, perhaps forecasting progress that we have seen in psychedelics research.

Hi Jack,

Right. The psychedelic work will probably be a more speculative and a lower-bound estimate. I expect we'll take the opportunity to cut our teeth on estimating the cost-effectiveness of research.

If we said we plan to evaluate projects in terms of their ability to save lives, would that rule out us evaluating something like research? I don't see how it would. You'd simply need to think about the effect that doing some research would have on the number of lives that are saved.

That's fair. Just copying my response to Samuel as I think it better explains where my query lies:

Extremely skeptical of this. Reading through Strong Minds' evidence base it looks like you're leaning very heavily on 2 RCTs of a total of about 600 people in Uganda, in which the outcomes were a slight reduction in a questionable mental health metric that relies on self-reporting.

You're making big claims about your intervention including that it is a better use of money than saving the lives of children. I hope you're right, otherwise you might be doing a lot of harm.

I weak downvoted this comment because of the following sentence:

"I hope you're right, otherwise you might be doing a lot of harm."

I agree that technically, a person who's very successful at advocating for a low impact intervention might do harm. But I think we should assume that most contributions to public discourse about cost-effectiveness are beneficial even if they are false.

Accusing people of doing harm makes it more difficult to discuss the issue in a distanced and calm way. It also makes it more difficult to get people contribute to those discussions.

Epistemic adjectives such as "unfounded", "weak", "false", "misleading" are still available, and these are less likely to provoke guilt and stifle discussion. Unless there are egregious violations of honesty, I don't think people should be accused of doing harm for defending their beliefs on cause-prioritisation.

Separately, I disagree voted because it seems wrong about the facts. HLI’s analysis relies on many different studies with a sample size >30K, as Michael explains below.

Hello Henry. It may look like we’re just leaning on 2 RCTs, but we’re not! If you read further down in the 'cash transfers vs treating depression' section, we mention that we compared cash transfers to talk therapy on the basis of a meta-analysis of each.

The evidence base for therapy is explained in full in Section 4 of our StrongMinds cost-effectiveness analysis. We use four direct studies and a meta-analysis of 39 indirect studies (n > 38,000). You can see how much weight we give to each source of evidence in Table 2, reproduced below. To be clear, we don’t take the results from StrongMinds' own trials at face value. We basically use an average figure for their effect size, even though they find a high figure themselves.

Also, what's wrong with the self-reports? People are self-reporting how they feel. How else should we determine how people feel? Should we just ignore them and assume that we know best? Also, we're comparing self-reports to other self-reports, so it's unclear what bias we need to worry about.

Regarding the issues of comparing saving lives to improving lives, we've just written a whole report on how to think about that. We're hoping that, by bringing these difficult issues to the surface - rather than glossing over them, which is what normally happens - people can make better-informed decisions. We're very much on your side: we think people should be thinking harder about which does more good.

I haven’t looked in detail at how Give Well evaluates evidence, so maybe you’re no worse here, but I don’t think “weighted average of published evidence” is appropriate when one has concerns about the quality of published evidence. Furthermore, I think some level of concern about the quality of published evidence should be one’s baseline position - I.e. a weighted average is only appropriate when there are unusually strong reasons to think the published evidence is good.

I’m broadly supportive of the project of evaluating impacts on happiness.

Hi David,

You’re right that we should be concerned with the quality of published evidence. I discounted psychotherapy's effect by 17% for having a higher risk of effect inflation than cash transfers, see Appendix C of McGuire & Plant (2021). However, this was the first pass at a fundamental problem in science, and I recognize we could do better here.

We’re planning on revisiting this analysis and improving our methods – but we’re currently prioritizing finding new interventions more than improving our analyses of old ones. Unfortunately, we currently don’t have the research capacity to do both well!

If you found this post helpful, please consider completing HLI's 2022 Impact Survey.

Most questions are multiple-choice and all questions are optional. It should take you around 15 minutes depending on how much you want to say.