Question

Do you think decreasing the consumption of animals is good/bad? For which groups of farmed animals?

Context

I stopped eating animals 4 years ago mostly to decrease the suffering of farmed animals[1]. I am glad I did that based on the information I had at the time, and published in online journals of my former university a series of 3 articles whose title reads "Why we should decrease the consumption of animals?". However, I am no longer confident that decreasing the consumption of animals is good/bad. It has many effects:

- Decreasing the number of factory-farmed animals.

- I believe this would be good for chickens, since I expect them to have negative lives. I estimated the lives of broilers in conventional and reformed scenarios are, per unit time, 2.58 and 0.574 times as bad as human lives are good (see 2nd table). However, these numbers are not resilient:

- On the one hand, if I consider disabling pain is 10 (instead of 100) times as bad as hurtful pain, the lives of broilers in conventional and reformed scenarios would be, per unit time, 2.73 % and 26.2 % as good as human lives. Nevertheless, disabling pain being only 10 times as bad as hurtful pain seems quite implausible if one thinks being alive is as good as hurtful pain is bad.

- On the other hand, I may be overestimating broilers’ pleasurable experiences.

- I guess the same applies to other species, but I honestly do not know. Figuring out whether farmed fish, shrimps and prawns have good/bad lives seems especially important. Together with chickens, they are arguably the driver for the welfare of farmed animals[2].

- I believe this would be good for chickens, since I expect them to have negative lives. I estimated the lives of broilers in conventional and reformed scenarios are, per unit time, 2.58 and 0.574 times as bad as human lives are good (see 2nd table). However, these numbers are not resilient:

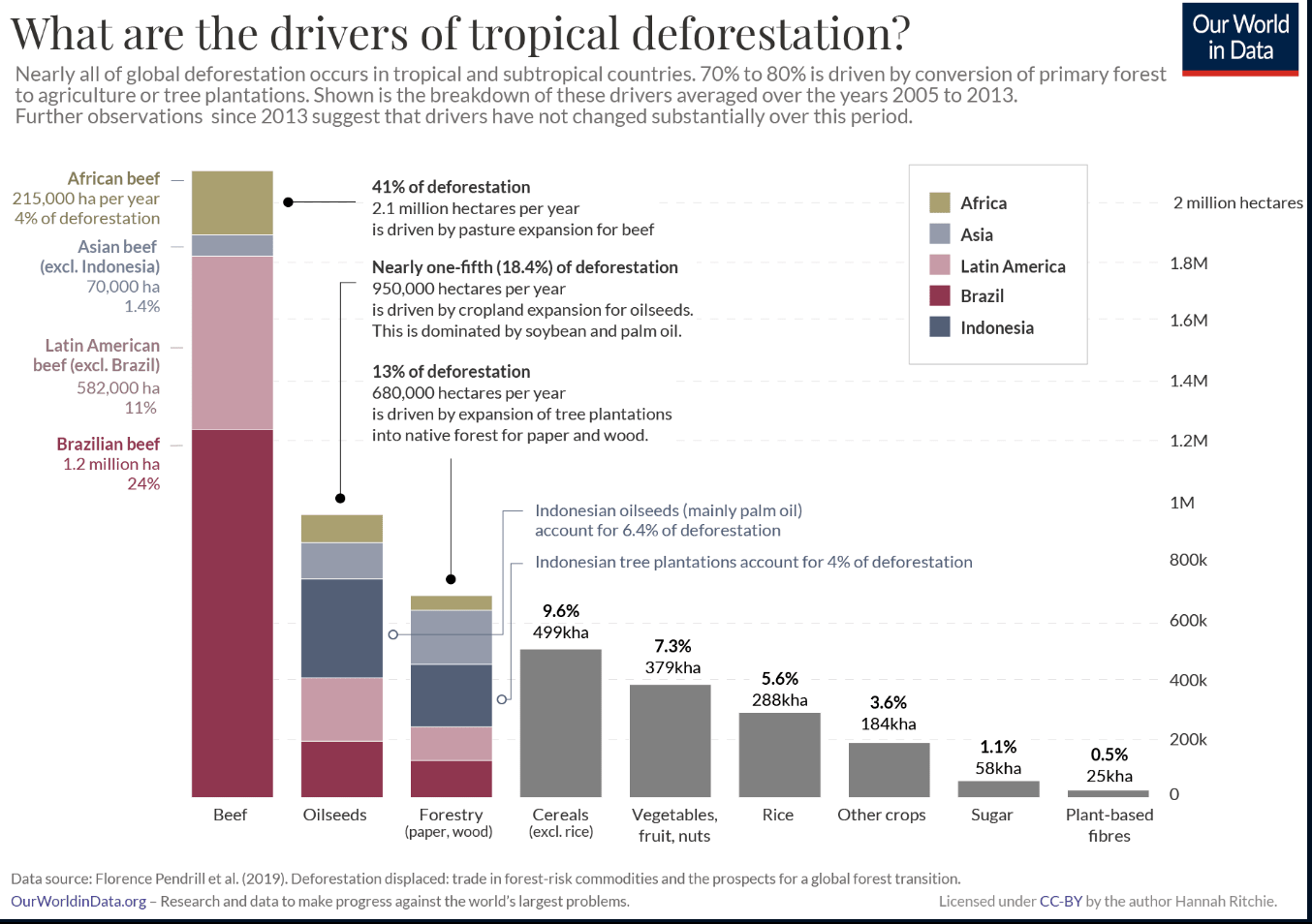

- Decreasing the production of animal feed, and therefore reducing crop area, which tends to:

- Increase the population of wild animals, which I do not know whether it is good or bad. I think the welfare of terrestrial wild animals is driven by that of terrestrial arthropods, but I am very uncertain about whether they have good or bad lives. I recommend checking this preprint from Heather Browning and Walter Weit for an overview of the welfare status of wild animals.

- Decrease the resilience against food shocks[3]. As I wrote here:

- The smaller the population of (farmed) animals, the less animal feed could be directed to humans to mitigate the food shocks caused by the lower temperature, light and humidity during abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios (ASRS), which can be a nuclear winter, volcanic winter, or impact winter[4].

- Because producing calories from animals is much less efficient than from plants, decreasing the number of animals results in a smaller area of crops.

- So the agricultural system would be less oversized (i.e. it would have a smaller safety margin), and scaling up food production to counter the lower yields during an ASRS would be harder.

- To maximise calorie supply, farmed animals should stop being fed and quickly be culled after the onset of an ASRS. This would decrease the starvation of humans and farmed animals, but these would tend to experience more severe pain for a faster slaughtering rate.

- As a side note, increasing food waste would also increase resilience against food shocks, as long as it can be promptly cut down. One can even argue humanity should increase (easily reducible) food waste instead of the population of farmed animals. However, I suspect the latter is more tractable.

- Increase biodiversity, which arguably increases existential risk due to ecosystem collapse (see Kareiva 2018).

- Decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore decreasing global warming.

- I have little idea whether this is good or bad.

- Firstly, it is quite unclear whether climate change is good or bad for wild animals.

- Secondly, although more global warming makes climate change worse for humans, I believe it mitigates the food shocks caused by ASRSs[5]. Accounting for both of these effects, I estimated the optimal median global warming in 2100 relative to 1880 can range from 0.1 to 4.3 ºC. I think the plausible range of the optimal global warming is even wider, because I have neglected many sources of uncertainty in my estimate above (like the impact of ASRSs on the energy system, which depends on the fraction of energy coming from fossil fuels).

- Improving human health[6], and therefore increasing productivity / economic growth.

- Better health is good because it leads to greater wellbeing, but economic growth has questionable longterm effects.

- In the last few hundred years, economic growth has been associated with better living conditions (good), but also with higher existential risk (bad).

- I think the focus should be on differential progress, but I do not know whether better health, and greater economic growth contribute positively or negatively to that.

- Decreasing the risk from pandemics linked to zoonotic diseases.

- Mitigating antimicrobial resistance:

- From Carrique-Mas 2020, "the greatest quantities of antimicrobials (in decreasing order) were used in pigs (41.7% of total use), humans (28.3%), aquaculture (21.9%) and chickens (4.8%). Combined AMU in other species accounted for < 1.5%".

- Boeckel 2015 projects that "antimicrobial consumption [in livestock production] will rise by 67% by 2030 [relative to 2010]".

- Expanding the moral circle to farmed animals, as changes in behaviour (eating less animals) can cascade into changes in values (caring about animals).

- This is good for farmed animals, but might be bad for wild animals if they have negative lives, and consuming less animals spreads memes of non-interference and environmentalism.

- On the other hand, the reduction in the consumption of animals could be good for wild animals if achieved through increasing the concern for all forms of suffering, regardless of whether or not it is caused by humans.

- Changes in values can potentially be locked (for example, via advanced artificial intelligence), and therefore have beneficial/harmful longterm effects.

- Decreasing the number of potential working animals like cows, which could be useful in scenarios where there is a major widespread loss of industry or electricity.

There is also uncertainty regarding how much a decrease in consumption translates to a reduction in production, but I think this mainly affects the magnitude of the overall effect, not its sign. It looks like Peter Singer's Animal Liberation Now does not adequately address my concerns.

For further context, feel free to check Brian Tomasik’s essays on reducing suffering, which introduced me to the indirect effects of changing the consumption of animals. I believe this post is a good place to start. Bear in mind Brian subscribes to negative utilitarianism.

My answer

Having the previous factors in mind, I do not know whether it is good/bad to decrease the consumption of animals at scale. Brian tends to agree:

If I could press a button to reduce overall meat consumption or to increase concern for animals, I probably would. In other words, I think the expected value of these things is perhaps slightly above zero. But my expected value for them is sufficiently close to zero that I don't feel great about my donations being used for them.

I also feel like decreasing the consumption of animals is positive, but suppose I am biassed towards overweighting the identifiable decrease in severe pain caused to factory-farmed animals. I guess welfarist approaches (e.g. corporate campaigns for chicken welfare) are more robustly beneficial than abolitionist ones (e.g. promotion of veganism), but both arguably decrease the consumption of animals, which can be either beneficial or harmful.

In any case, I plan to continue following a whole-food plant-based diet[7], because:

- I would say it makes me healthier and happier, and therefore more productive.

- It makes me happier not only due to improved health, but also because causing severe pain to factory-farmed animals would feel pretty bad.

- Based on these data from the Welfare Footprint Project, supposing each broiler provides 2 kg of edible meat, and that the elasticity of production with respect to consumption is 0.5[8], eating 100 g of chicken causes 75.4 min (= 50.27*60/2*0.1*0.5) of disabling pain if it is produced in a conventional scenario, and 25.9 min (= 17.26*60/2*0.1*0.5) if in a reformed one[9].

- I guess (hope?) I am overall contributing to a better world, in which case increased productivity is good.

These arguably do not apply to the general population. I believe it is quite hard to tell whether a random person is overall making a positive/negative contribution to the world, essentially for the same reasons I prefer differential progress to economic growth.

Nevertheless, I suspect most people would claim they are overall contributing to a better world. Consequently, according to the reasoning above, they would decide on eating animals based on impacts on productivity, i.e. adopt the “anything goes” approach described by Rob Bensinger. Overall, boycott-itarianism, only eating animals which have sufficiently high welfare, seems better.

Finally, it is worth noting the impact of a random person on farmed animals can apparently be neutralised at a very low cost. I guess it is of the order of magnitude of 0.147 $/year (= 4.64/31.5), as I estimated:

- The cost-effectiveness of corporate campaigns for broiler welfare is equivalent to creating 31.5 human-years per dollar.

- The lives of all farmed animals combined are 4.64 times as bad as the lives of all humans combined are good.

Even if the real cost is 100 times higher, most people would more easily donate 14.7 $/year (= 0.147*100) to, for example, Animal Charity Evaluators' top charities than follow a plant-based diet?

Acknowledgements

Thanks to David Denkenberger, Stijn Bruers, Julian Jamison, and Ariel Simnegar for feedback on a draft[10].

- ^

In addition, improving health, and mitigating global warming played a minor role. Fun fact, Lewis Bollard’s 1st appearance on The 80,000 Hours Podcast was an important part of my investigation of the conditions of farmed animals.

- ^

Note I also care about the welfare of large animals like pigs and cows/bulls.

- ^

I first heard about this from Michael Hinge’s appearance on Hear This Idea.

- ^

Additionally, a smaller population of animals would result in a smaller stock of animals and edible animal feed, and larger stock of plant-based foods to be eaten during the ASRS. Nonetheless, these effects would be smaller than the reduction in the production of edible animal feed.

- ^

This occurred to me during a meeting with people from Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters (ALLFED).

- ^

The EAT-Lancet diet only has 12.2 % (= (153 + 30 + 62 + 19 + 40)/2500; see Table 1) of calories coming from animals, and, according to the results of 3 approaches, would decrease adult deaths by 21.7 % (= (0.19 + 0.224 + 0.236)/3; see Table 2). This suggests decreasing the consumption of animals improves health at the margin, even if it is unclear whether the optimal consumption of animal products is zero.

- ^

Fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes, berries, nuts, seeds, herbs, spices, water, and supplements.

- ^

The elasticity will be something between 0 and 1, so I used 0.5. However, it looks like there is significant uncertainty.

- ^

The Welfare Footprint Project defines disabling pain as follows:

Pain at this level takes priority over most bids for behavioral execution and prevents all forms of enjoyment or positive welfare. Pain is continuously distressing. Individuals affected by harms in this category often change their activity levels drastically (the degree of disruption in the ability of an organism to function optimally should not be confused with the overt expression of pain behaviors, which is less likely in prey species). Inattention and unresponsiveness to milder forms of pain or other ongoing stimuli and surroundings is likely to be observed. Relief often requires higher drug dosages or more powerful drugs. The term Disabling refers to the disability caused by ‘pain’, not to any structural disability.

- ^

Names ordered by descending relevance of contributions.

Thanks for commenting, Joe!

I think that is definitely an important point, and it makes me believe the conditions of factory-farmed animals should be improved such that their rights are less violated. However, I do not know whether it outweights other factors like the increased human starvation in abrupt sunlight reduction scenarios, and potentially preventing wild animals from having good lives. Copy-pasting from my reply further down:

... (read more)I'm Not a Speciesist; I'm Just a Utilitarian. Great piece from Brian Tomasik illustrating key differences between animals and humans:

... (read more)