YouGov recently reported the results of a survey (n=1000) suggesting that about “one in five (22%) Americans are familiar with effective altruism.”[1]

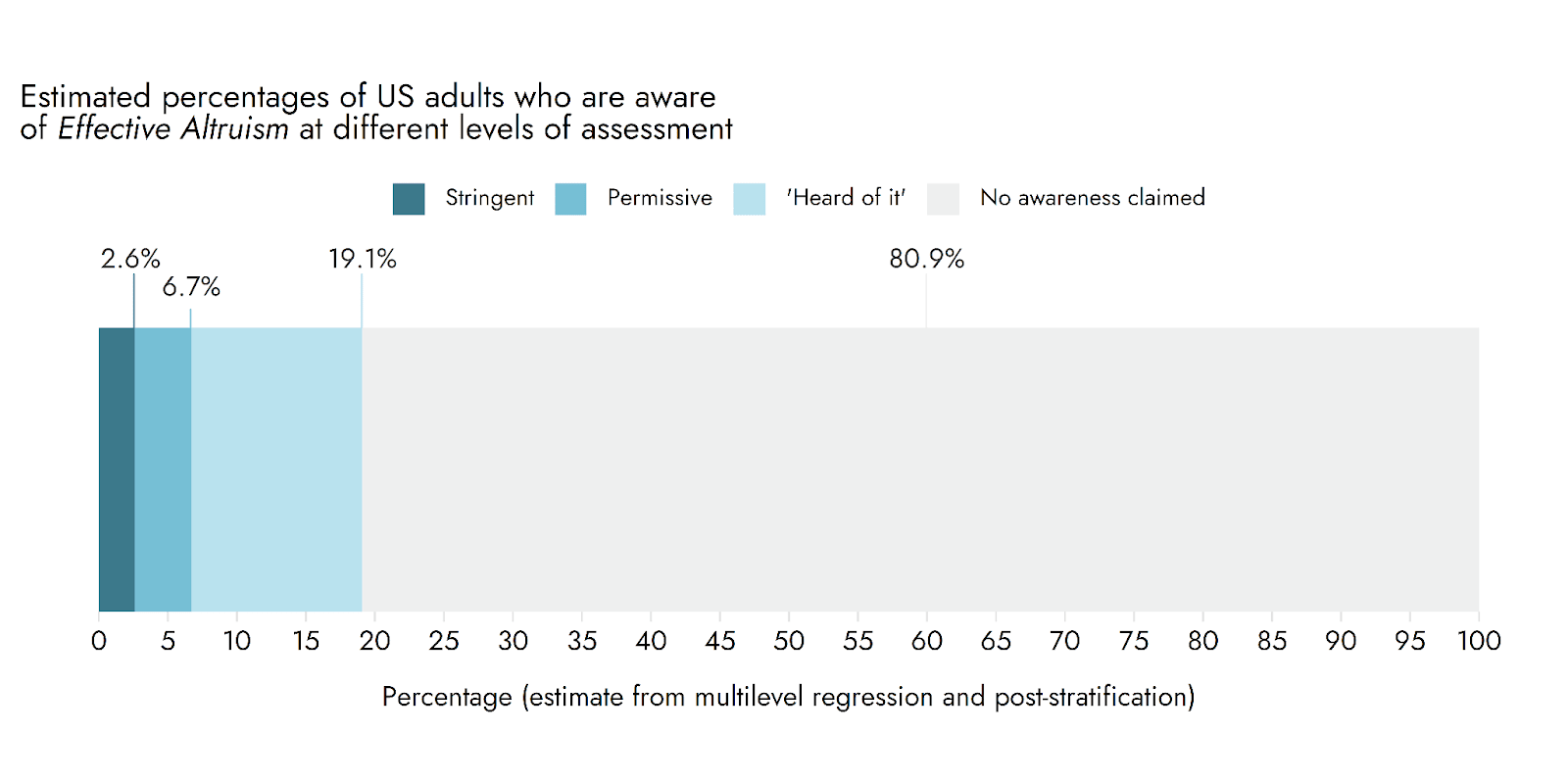

We think these results are exceptionally unlikely to be true. Their 22% figure is very similar to the proportion of Americans we previously found claim to have heard of effective altruism (19%) in our earlier survey (n=6130). But, after conducting appropriate checks, we estimated that much lower percentages are likely to have genuinely heard of EA[2] (2.6% after the most stringent checks, which we speculate is still likely to be somewhat inflated[3]).

Is it possible that these numbers have simply dramatically increased following the FTX scandal?

Fortunately, we have tested this with multiple followup surveys explicitly designed with this possibility in mind.[4]

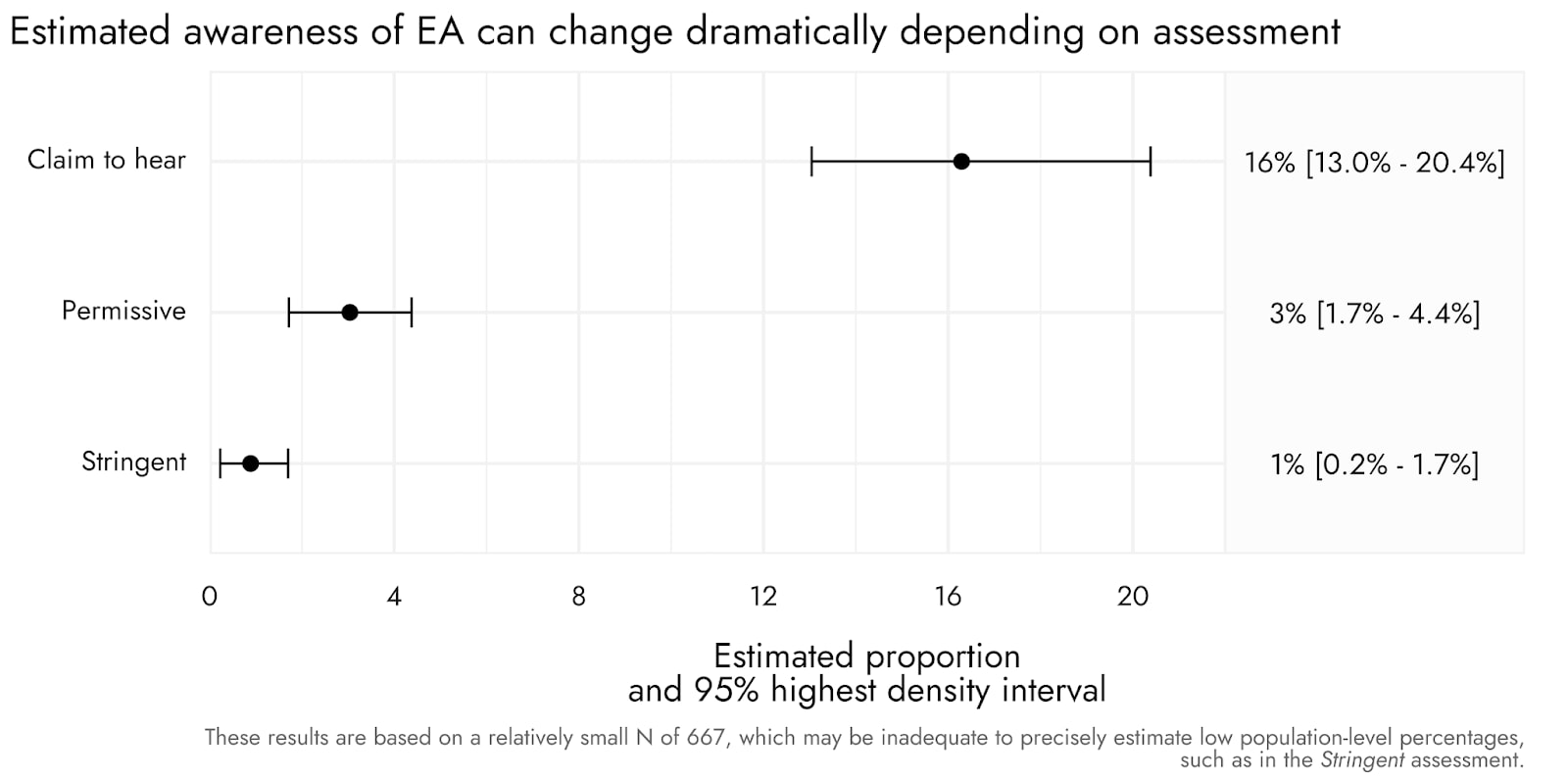

In our most recent survey (conducted October 6th[5]), we estimated that approximately 16% (13.0%-20.4%) of US adults would claim to have heard of EA. Yet, when we add in additional checks to assess whether people appear to have really heard of the term, or have a basic understanding of what it means, this estimate drops to 3% (1.7% to 4.4%), and even to approximately 1% with a more stringent level of assessment.[6]

These results are roughly in line with our earlier polling in May 2022, as well as additional polling we conducted between May 2022 and October 2023, and do not suggest any dramatic increase in awareness of effective altruism, although assessing small changes when base rates are already low is challenging.

We plan to continue to conduct additional surveys, which will allow us to assess possible changes from just before the trial of Sam Bankman-Fried to after the trial.

Attitudes towards EA

YouGov also report that respondents are, even post-FTX, overwhelmingly positive towards EA, with 81% of those who (claim to) have heard of EA approving or strongly approving of EA.

Fortunately, this positive view is broadly in line with our own findings- across different ways of breaking down who has heard of EA and different levels of stringency- which we aim to report on separately at a later date. However, our earlier work did find that awareness of FTX was associated with more negative attitudes towards EA.

Conclusions

The point of this post is not to criticise YouGov in particular. However, we do think it’s worth highlighting that even highly reputable polling organizations should not be assumed to be employing all the additional checks that may be required to understand a particular question. This may apply especially in relation to niche topics like effective altruism, or more technical topics like AI, where additional nuance and checks may be required to assess understanding.

- ^

Also see this quick take.

- ^

There are many reasons why respondents may erroneously claim knowledge of something. But simply put, one reason is that people like demonstrating their knowledge, and may err on the side of claiming to have heard of something even if they are not sure. Moreover, if the component words that make up a term are familiar, then the respondent may either mistakenly believe they have already encountered the term, or think it is sufficient that they believe they can reasonably infer what the term means from its component parts to claim awareness (even when explicitly instructed not to approach the task this way!). Some people also appear to conflate the term with others - for example, some amalgamation of inclusive fitness/reciprocal altruism appears quite common.

For reference, in another check we included, over 12% of people claim to have heard of the specific term “Globally neutral advocacy”: A term that our research team invented, which returns no google results as a quote, and which is not recognised as a term by GPT—a large-language model trained on a massive corpus of public and private data. “Globally neutral advocacy” represents something of a canary for illegitimate claims of having heard of EA, in that it is composed of terms people are likely to know, and the combination of which they might reasonably think they can infer the meaning or even simply mistakenly believe they have encountered.

- ^

For example, it is hard to prevent a motivated respondent from googling “effective altruism” in order to provide a reasonable open comment explanation of what effective altruism means. However, we have now implemented additional checks to guard against this.

- ^

- ^

n=1300 respondents overall, but respondents were randomly assigned to receive one of two different question formats to assess their awareness of EA. Results were post-stratified to be representative of US adults. This is a smaller sample size than we typically recommend for nationally representative sample, as this was an intermediate, 'pre-test' survey, and hence the error bars around these estimates are relatively wider than they otherwise would be. A larger N would be especially useful for more robustly determining the rates of low incidence outcomes (such as awareness of niche topics).

- ^

As an additional check, we also assessed EA awareness using an alternative approach, in which a different subset of the respondents were shown the term and its definition, then asked if they knew the term only, the term and associated ideas, only the ideas, or neither the term nor the ideas. Using this design, approximately 15% claimed knowledge either of the term alone or both the term and ideas, while only 5% claimed knowlege of the term and the ideas.

What are the stringent and permissive criteria for judging that someone has heard of EA?

The full process is described in our earlier post, and included a variety of other checks as well.

But, in brief, the "stringent" and "permissive" criteria refer to respondents' open comment explanations of what they understand "effective altruism" to means, and whether they either displayed clear familiarity with effective altruism, such that it would be very unlikely someone would give that response if they were not genuinely familiar with effective altruism (e.g. by referring to using evidence and reason to maximise the amount of good done with you... (read more)