And other ways to make event content more valuable.

I organise and attend a lot of conferences, so the below is correct and need not be caveated based on my experience, but I could be missing some angles here. Also on my substack.

When you imagine a session at an event going wrong, you’re probably thinking of the hapless, unlucky speaker. Maybe their slides broke, they forgot their lines, or they tripped on a cable and took the whole stage backdrop down.

This happens sometimes, but event organizers usually remember to invest the effort required to prevent this from happening (e.g., checking that the slides work, not leaving cables lying on the stage).

But there’s another big way that sessions go wrong that is sorely neglected: wasting everyone’s time, often without people noticing.

Let’s give talks a break. They often suck, but event organizers are mostly doing the right things to make them not suck. I’m going to pick on two event formats that (often) suck, why they suck, and how to run more useful content instead.

Panels

Panels. (very often). suck.

Reid Hoffman (and others) have already explained why, but this message has not yet reached a wide enough audience:

Because panelists know they'll only have limited time to speak, they tend to focus on clear and simple messages that will resonate with the broadest number of people. The result is that you get one person giving you an overly simplistic take on the subject at hand. And then the process repeats itself multiple times! Instead of going deeper or providing more nuance, the panel format ensures shallowness.

Even worse, this shallow discourse manifests as polite groupthink. After all, panelists attend conferences for the same reasons that attendees do – they want to make connections and build relationships. So panels end up heavy on positivity and agreement, and light on the sort of discourse which, through contrasting opinions and debate, could potentially be more illuminating.

The worst form of shal

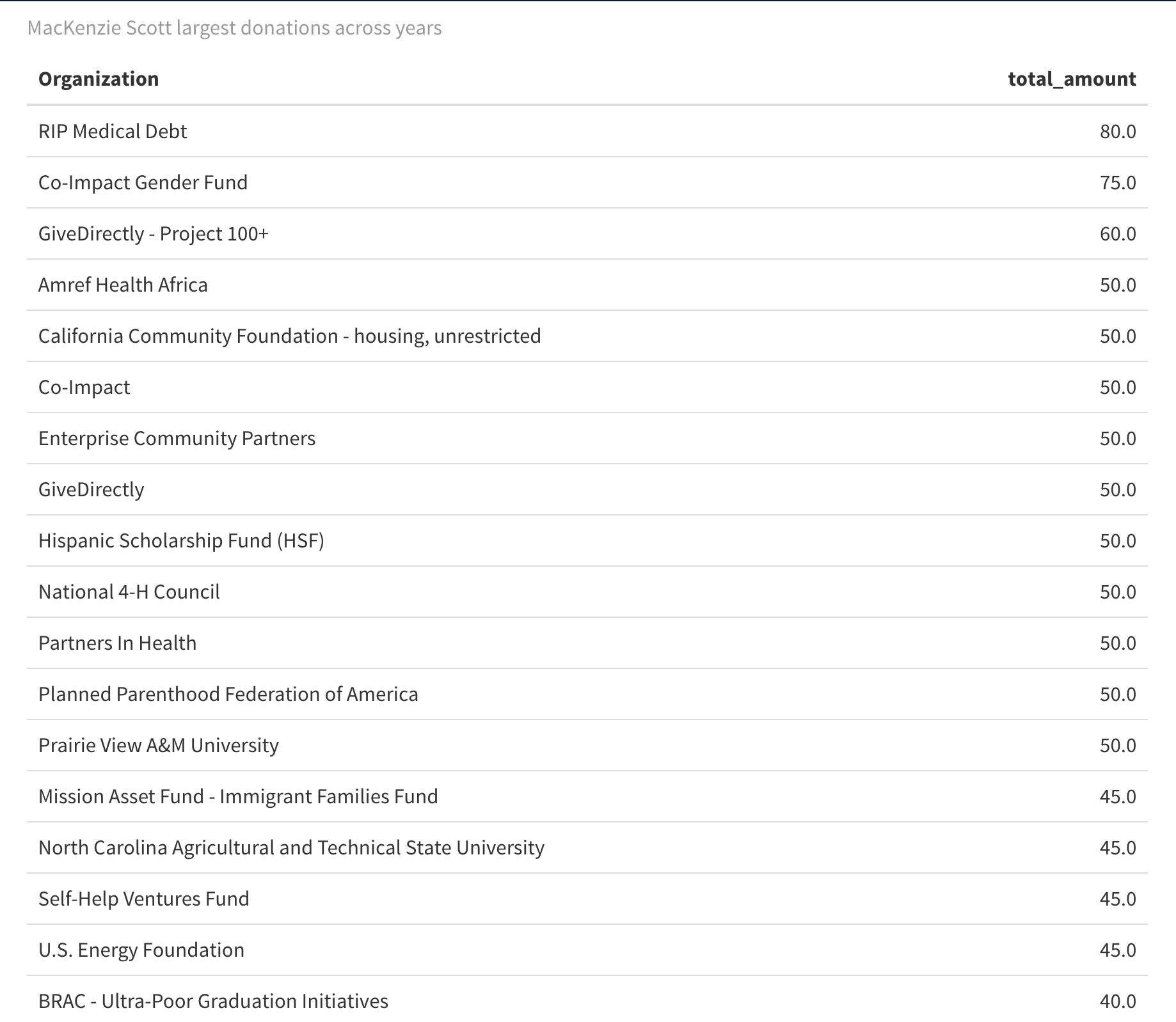

I looked up RIP Medical Debt out of curiosity, and the concept is pretty cool if it works / is true. From their website:

“You make a donation We use data analytics to pinpoint the debt of those most in need: households that earn less than 4x the federal poverty level (varies by state, family size) or whose debts are 5% or more of annual income.

RIP buys medical debt at a steep discount We buy debt in bundles, millions of dollars at a time at a fraction of the original cost.

This means your donation relieves about 100x its value in medical debt. Together we wipe out medical debt People across the country receive letters that their debt has been erased. They have no tax consequences or penalties to consider. Just like that, they’re free of medical debt.”

That's a question about the market for debt, which is not particularly transparent. I think it's something that FTC economists probably could get some information about, since the FTC has a fair amount of insight into debt collection, but otherwise I think it's going to be very hard to answer. Also, see my other comment about collectibility and value.