It's common for people who approach helping animals from a quantitative direction to need some concept of "moral weights" so they can prioritize. If you can avert one year of suffering for a chicken or ten for shrimp which should you choose? Now, moral weight is not the only consideration with questions like this, since typically the suffering involved will also be quite different, but it's still an important factor.

One of the more thorough investigations here is Rethink Priorities' moral weights series. It's really interesting work and I'd recommend reading it! Here's a selection from their bottom-line point estimates comparing animals to humans:

| Humans | 1 (by definition) |

| Chickens | 3 |

| Carp | 11 |

| Bees | 14 |

| Shrimp | 32 |

If you find these surprisingly low, you're not alone: that giving a year of happy life to twelve carp might be more valuable than giving one to a human is for most people a very unintuitive claim. The authors have a good post on this, Don't Balk at Animal-friendly Results, that discusses how the assumptions behind their project make this kind of result pretty likely and argues against putting much stock in our potentially quite biased initial intuitions.

What concerns me is that I suspect people rarely get deeply interested in the moral weight of animals unless they come in with an unusually high initial intuitive view. Someone who thinks humans matter far more than animals and wants to devote their career to making the world better is much more likely to choose a career focused on people, like reducing poverty or global catastrophic risk. Even if someone came into the field with, say, the median initial view on how to weigh humans vs animals I would expect working as a junior person in a community of people who value animals highly would exert a large influence in that direction regardless of what the underlying truth. If you somehow could convince a research group, not selected for caring a lot about animals, to pursue this question in isolation, I'd predict they'd end up with far less animal-friendly results.

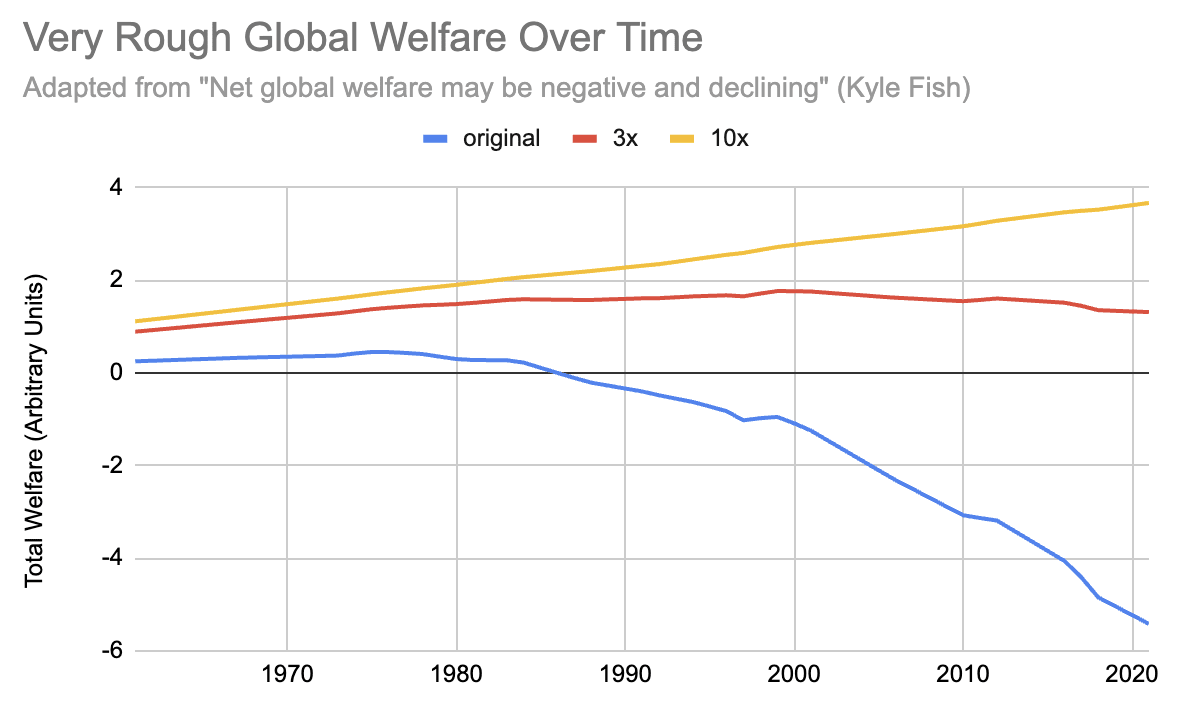

When using the moral weights of animals to decide between various animal-focused interventions this is not a major concern: the donors, charity evaluators, and moral weights researchers are coming from a similar perspective. Where I see a larger problem, however, is in broader cause prioritization, such as Net Global Welfare May Be Negative and Declining. The post weighs the increasing welfare of humanity over time against the increasing suffering of livestock, and concludes that things are likely bad and getting worse. If you ran the same analysis with different inputs, such as what I'd expect you'd get from my hypothetical research group above, however, you'd instead conclude the opposite: global welfare is likely positive and increasing.

For example, if that sort of process ended up with moral weights that were 3x lower for animals relative to humans we would see approximately flat global welfare, while if they were 10x lower we'd see increasing global welfare:

See sheet to try your own numbers; original chart digitized with via graphreader.com.

Note that both 3x and 10x are quite small compared to the uncertainty involved in coming up with these numbers: in different post the Rethink authors give 3x (and maybe as high as 10x) just for the likely impact of using objective list theory instead of hedonism, which is only one of many choices involved in estimating moral weights.

I think the overall project of figuring out how to compare humans and animals is a really important one with serious implications for what people should work on, but I'm skeptical of, and put very little weight on, the conclusions so far.

This could depend on your population ethics and indirect considerations. I'll assume some kind of expectational utilitarianism.

The strongest case for extinction and existential risk reduction is on a (relatively) symmetric total view. On such a view, it all seems dominated by far future moral patients, especially artificial minds, in expectation. Farmed animal welfare might tell us something about whether artificial minds are likely to have net positive or net negative aggregate welfare, and moral weights for animals can inform moral weights for different artificial minds and especially those with limited agency. But it's relatively weak evidence. If you expect future welfare to be positive, then extinction risk reduction looks good and (far) better in expectation even with very low probabilities of making a difference, but could be Pascalian, especially for an individual (https://globalprioritiesinstitute.org/christian-tarsney-the-epistemic-challenge-to-longtermism/). The Pascalian concerns could also apply to other population ethics.

If you have narrow person-affecting views, then cost-effective farmed animal interventions don’t generally help animals alive now, so won't do much good. If death is also bad on such views, extinction risk reduction would be better, but not necessarily better than GiveWell recommendations. If death isn't bad, then you'd pick work to improve human welfare, which could include saving the lives of children for the benefit of the parents and other family, not the children saved.

If you have asymmetric or wide person-affecting views, then animal welfare could look better than extinction risk reduction depending on human vs nonhuman moral weights and expected current lives saved by x-risk reduction, but worse than far future quality improvements or s-risk reduction (e.g. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/phpr.12927, but maybe animal welfare work counts for those, too, and either may be Pascalian). Still, on some asymmetric or wide views, extinction risk reduction could look better than animal welfare, in case good lives offset the bad ones (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/phpr.12927). Also, maybe extinction risk reduction could look better for indirect reasons, e.g. replacing alien descendants with our happier ones, or because the work also improves the quality of the far future conditional on not going extinct.

EDIT: Or, if the people alive today aren't killed (whether through a catastrophic event or anything else, like malaria), there's a chance they'll live very very long lives through technological advancement, and so saving them could at least beat the near-term effects of animal welfare if dying earlier is worse on a given person-affecting view.

That being said, all the above variants of expectational utilitarianism are irrational, because unbounded utility functions are irrational (e.g. can be money pumped, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/phpr.12704), so the standard x-risk argument seems based on jointly irrational premises. And x-risk reduction might not follow from stochastic dominance or expected utility maximization on all bounded increasing utility functions of total welfare (https://globalprioritiesinstitute.org/christian-tarsney-the-epistemic-challenge-to-longtermism/ and https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.10895; the argument for riskier bets here also depends on wide background value uncertainty, which would be lower with lower moral weights for nonhuman animals; stochastic dominance is equivalent to higher expected utility on all bounded increasing utility functions consistent with the (pre)order in deterministic cases).