I often use the following thought experiment as an intuition pump to make the ethical case for taking expected value, risk/uncertainty-neutrality,[1] and math in general seriously in the context of doing good. There are, of course, issues with pure expected value maximization (e.g. Pascal’s Mugging, St. Petersburg paradox and infinities, etc), that I won’t go into in this post. I think these considerations are often given too much weight and applied improperly (which I also won’t discuss in this post).

This thought experiment isn’t original, but I forget where I first encountered it. You can still give me credit if you want. Thanks! The graphics below are from Claude, but you can also give me credit if you like them (and blame Claude if you don’t). Thanks again.

Thought experiment:

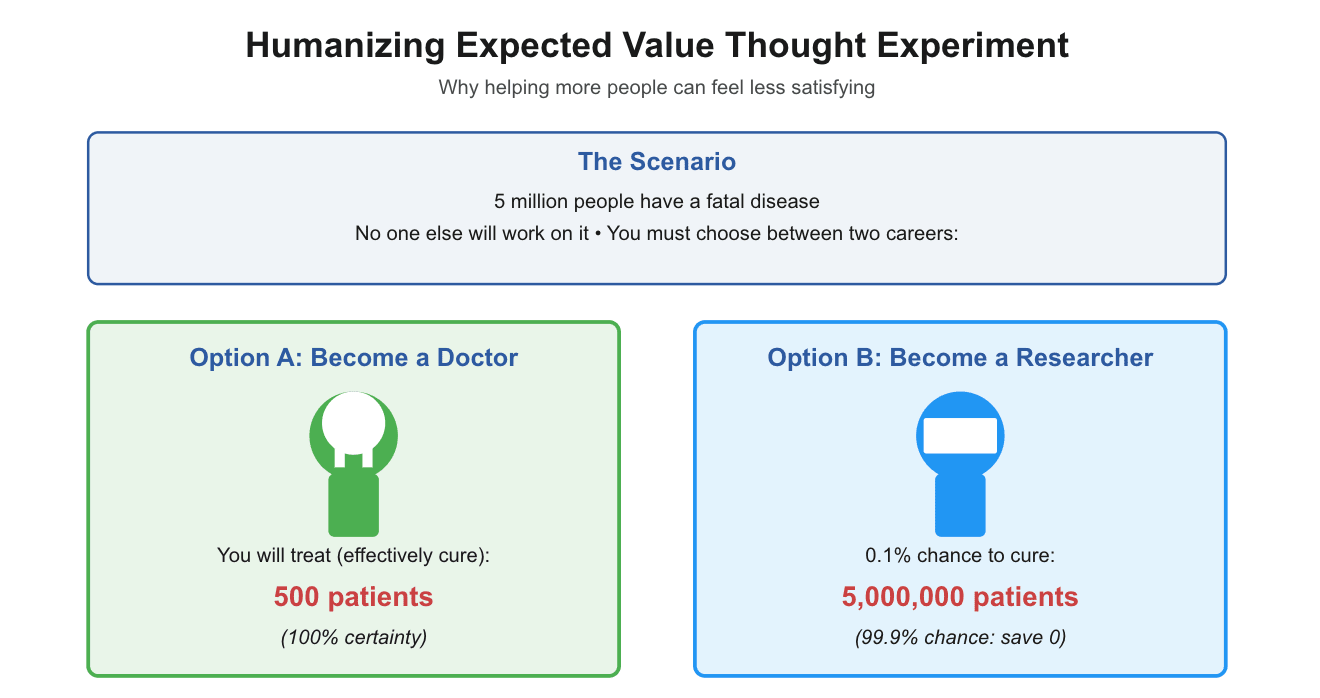

Say there's this new, obscure, debilitating disease that affects 5 million people, who will die in the next ten years if not treated. It has no known cure, and for whatever reason, I know nobody else is going to work on it. I’m considering two options for what I could do with my career to tackle this disease.

Option A: I can become a doctor and estimate I’ll be able to treat 500 patients over the coming ten years, where treating them is equivalent to curing them of the disease.

Option B: I can become a researcher, and I'd have a 0.1% chance of successfully developing a cure to the disease which would save all 5 million patients over the next ten years. But in 99.9% of worlds, I end up making no progress and don't end up saving any lives. The work I do doesn't end up helping other researchers get closer to coming up with a cure.

Given these two options, should I become a doctor or a researcher? Many people intuitively would think: "Man, saving 500 patients over the next ten years? That's definitely a career I can be proud of, and I’d have a ton of impact. With Option A, I know I'll get to save 500 people, and with the other option, there is a 99.9% chance that I don't end up saving anyone. Those odds aren’t great, and it’d be pretty rough to live my life knowing in all likelihood I won’t end up saving anyone."

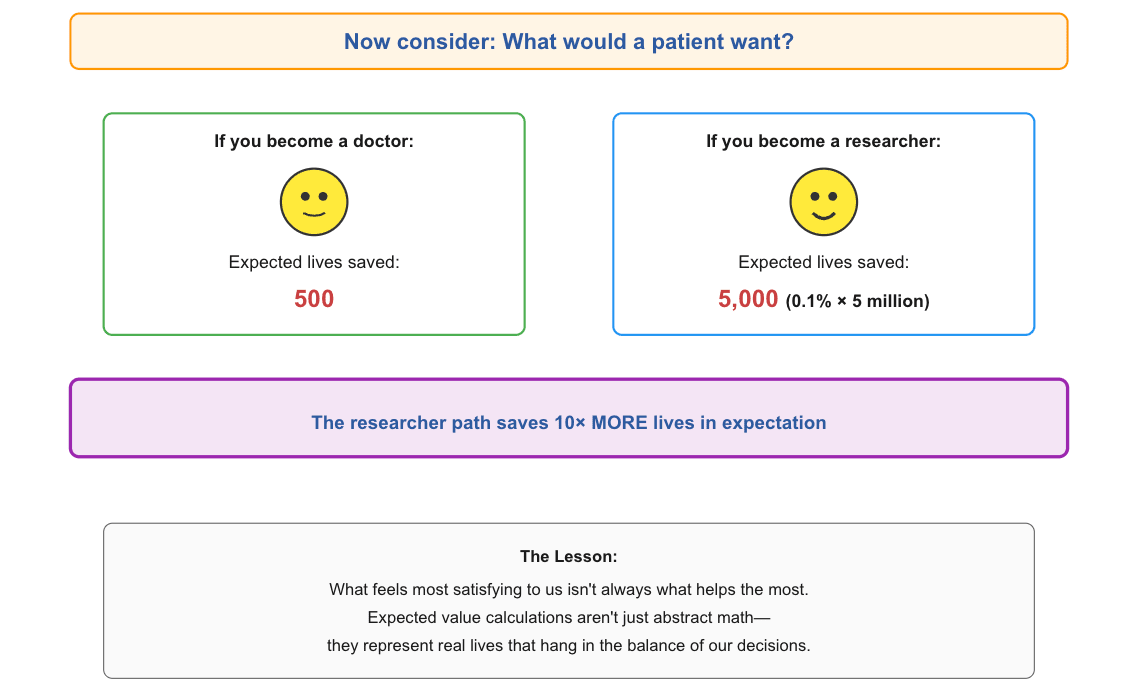

But consider the perspective of a random person with this disease. From their perspective, since they know that the doctor will save 500 patients out of the 5 million who have the disease, there is a 0.01% chance that they would get treated/cured if I chose to become a doctor. However, their chances of getting cured are 0.1% if I choose to become a researcher. So from their perspective, they would be ten times more likely to survive, if I choose to become a researcher instead of becoming a doctor.

This thought experiment simplifies things a lot, and reality is rarely this straightforward. But it is helpful for putting things in perspective. If what seems best to me as an altruist differs from what seems best to the beneficiaries I’m trying to help, I should be skeptical that my intuitions and preferences are actually impact-maximizing.

It also humanizes expected value calculations and all the math that often comes up when discussing effective altruism. To us, multiplying 5 million by 0.1% can just feel like math. But there really are lives at stake in the decisions we make, whether or not we see them with our own eyes.

I want to be serious about actually helping others as much as I can – and not be satisfied with doing what feels good enough. It’s extremely important to be vigilant about cognitive biases and motivated reasoning, and try my best to do what’s right even when it’s hard. Unlike with my thought experiment, many moral patients - especially animals and future sentience - won’t (and often can't) tell us when we could be helping them much more. We need to figure out how ourselves.

- ^

I think being downside-risk/loss-averse is usually more justified than being uncertainty-averse. If anything, given general dispositional aversion to uncertainty, I think prioritizing higher-uncertainty options is often likely to be the correct call altruistically speaking (especially when the downsides are lost time or money like in the above example, as opposed to counterfactual harm), since said options are more likely to be neglected. This seems to be the case in the EA community (especially in GHW and animal welfare), and the rest of the world.

Ooh this is neat.

I like how it neutralizes the certainty-seeking part of me since it's only me, the difference maker, that has the option of a guaranteed 100% outcome. For the beneficiary, it's always a gamble.

You're preaching to the choir here on the EA forum but I think most people outside this community will intuit the slippery slope that this takes you down:

0.1% x 5 million lives saved is the same EV as 0.0000001% chance of 5 trillion lives saved

Somewhere between those two this becomes a Pascal's Mugging that we seem to generally agree is a bad reason to do something.

Where's the line?

Feels like there's some line where your numbers are getting so tiny and speculative that many other considerations start dominating, like "are your numbers actually right?" E.g. I'd be pretty skeptical of many proposed ".000001% of huge number" interventions (especially skeptical on the on the .000001% side).

In practice, the line could be where "are your numbers actually right" starts becoming the dominant consideration. At that point, proving your numbers are plausible is the main challenge that needs to be overcome - and is honestly where I suspect most people's anti-low-probabilities intuitions come from in the first place.

Great post! Was just thinking about an intuition pump of my own re: EV earlier today, and it has a similar backdrop, of vaccine development. Also, you gave me a line with which to lead into it:

Oh but it could have helped! It probably does (but there are exceptions like if your work is heavily misguided to the degree that nobody would have worked on it, or is gated).

By doing the work and showing it doesn't lead to a cure, you're freeing someone else who would have done that work to do some other work instead. Assuming they would still be searching for a cure, you've increased the probability that the remaining researchers do in fact find a cure.

I encounter "in 99.9% of worlds, I end up making no progress" a lot in my work, and I offer in its place that it is important and valuable to chase down many different bets to their conclusions, that the vaccine is not developed by a single party alone in isolation from all the knowledge being generated around them, but through the collected efforts of thousands of failed attempts from as many groups. The victor can claim only the lion's share of the credit, not all of it; every (plausible) failed attempted gets some part of the value generated from the endeavour as a whole, even ex post.

Very good thought experiment. The point is correct. The problem is that in real life we almost never know the probability of anything. So, it will almost never happen that someone knows a long shot bet has 10x better expected value than a sure thing. What will happen in almost every case is that a person faces irreducible uncertainty and takes a bet. That’s life and it ain’t such a bad gig.

Sounds like a cause X, helping people gain clarity on tractable subsets of the general issue you mentioned... although as I write this I realise 80K and Probably Good etc are a thing, their qualitative advice is great, and they've argued against doing the quantitative version. (Some people disagree but they're in the minority and it hasn't really caught on in the couple of years I've paid attention to this.)

I think the uncertainty is often just irreducible. Someone faces the choice of either becoming an oncologist who treats patients or a cancer researcher. They don't know which option has higher expected value because they don't know the relevant probabilities. And there is no way out of that uncertainty, so they have to make a choice with the information they have.

You can't know with certainty, but any decision you make is based on some implicit guesses. This seems to be pretending that the uncertainty precludes doing introspection or analysis - as if making bets, as you put it, must be done blindly.

No, irreducible uncertainty is not all-or-nothing. Obviously a person should do introspection and analysis when making important decisions.

Nice post and visualization! You might be interested in a different but related thought experiment from Richard Chappell.

Thanks for this!

First came across a similar argument in Joe Carlsmith's series on expected utility (this section in particular). The rest of that essay has some other interesting arguments, though the one you've highlighted here is the part I've generally found myself remembering and coming back to most.

I think this post would be pretty helpful (short yet string argument) for a (university or other) intro fellowship -- if you can add/substitute a reading to your current intro fellowship, consider adding it to yours!

The argument sure is a string :P

absolutely love this perspective and i will definitely use a version of it in future explanations. thanks a lot!

You never miss Kuhan!

Hey Kuhan, I really liked this. Thanks for writing it. It led me to think a bit about how this applies to animal welfare.

What I really like about this, is how your thought experiment encourages altruists to think from the perspective of those they’re trying to help. That principle doesn’t just help humanize EV, it can also help with creating willingness to help individuals regardless of the cause of their suffering. An animal living in a fire zone probably doesn’t care if you’re helping them because humans are to blame or if nature is.

One of the difficulties in animal welfare (but maybe also in other cause areas I don't understand as well) is how uncertain probabilities are in many interventions, not just of success but also of potential backlash or other negative outcomes.

The other challenge when I try to apply this for animal welfare is that thinking from the individual’s perspective doesn’t necessarily result in the highest EV intervention. A hen suffering in a cage now might prefer a really low chance of a sanctuary rescue over a corporate welfare campaign that likely affects more chickens because the latter will only affect future birds. (And this thought-experiment hen could be super kind and utilitarian, but at a certain point I expect excruciating pain will be the main decision-making factor.) You can make an honest and strong values argument about how we must be willing to weigh the welfare of current and future hens equally, but some of the rhetorical power is lost.

An animal example (which Claude helped me come up with) that I think could potentially work for animal grantmakers is to imagine you’ll be born as a salmon into aquaculture who knows where. A funder can either:

I’d prefer not to be born as a salmon at all—and if I were, I might rather die before reaching the smolt phase—but if I knew I’d make it to slaughter age I would hope, depending on the details and the certainty of that 20%, the grantmaker would fund the R&D.