When you scroll through the Effective Altruism Forum you’ll find lots of economic analyses.

There is a tag for Economics with 161 posts, as well as one for Economic growth (130 posts), Economic inequality (10 posts), Economics of artificial intelligence (28 posts), Welfare economics (17 posts), Tax Policy (21 posts), Markets for altruism (33 posts) and many other subcategories.

Now I really like economics and I love economic analyses, but I think it’s very surprising how little presence the other social sciences have. The Social science tag only has 27 posts and there is no tag for sociology, anthropology, gender studies, geography, political science, or many other social sciences.

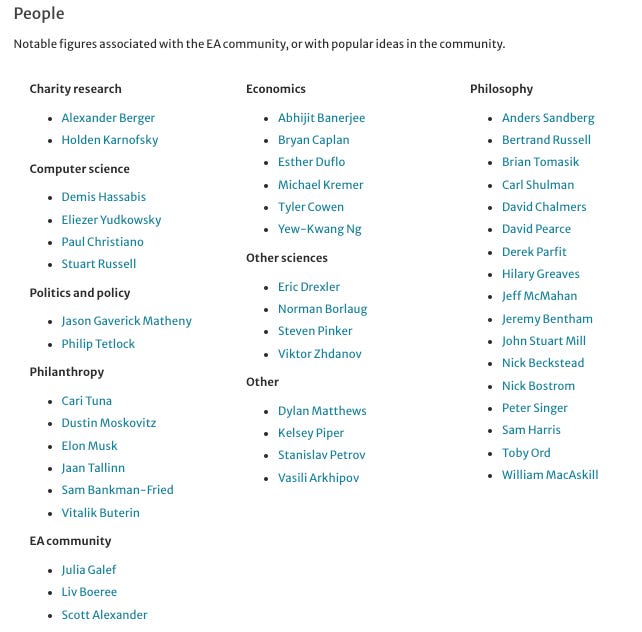

When you look at the People page of the EA forum, you’ll find lots of economists (and entrepreneurs) but almost no other social scientists. You will also notice that the vast majority of the people on this page are white men. This has been this way for a long time; this is what the page looked like a year ago:

I myself removed Elon Musk and SBF from this page, but don’t worry, this post will focus on the dangers of overrelying on economics, not on overrelying on capitalists (although they are related).

So what might those dangers be, and why is EA so stringent in its use of other disciplines? Well, those things are related too; economics is extremely insular. Other social studies make a lot of attempts to integrate themselves with all the other social sciences. This makes it so that learning about one discipline also teaches you about the other disciplines. Economists, meanwhile, have a tendency to see their discipline as better than the others, starting papers with things like:

Economics is not only a social science, it is a genuine science. Like the physical sciences, economics uses a methodology that produces refutable implications and tests these implications using solid statistical techniques.

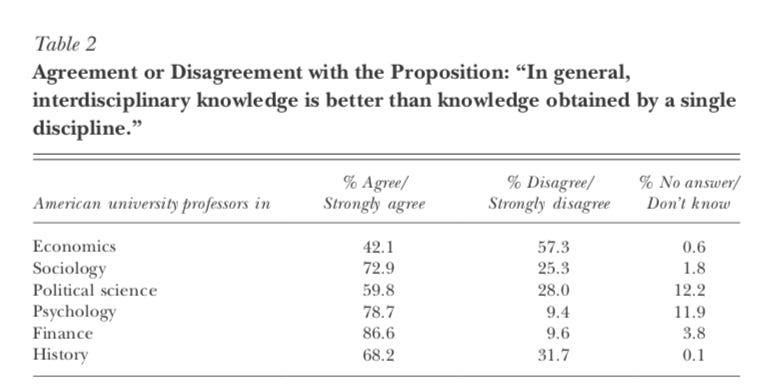

In the paper "The Superiority of Economists" by Fourcade et al, economists were found to be the only group that thought interdisciplinary research was worse than research from a singular field:

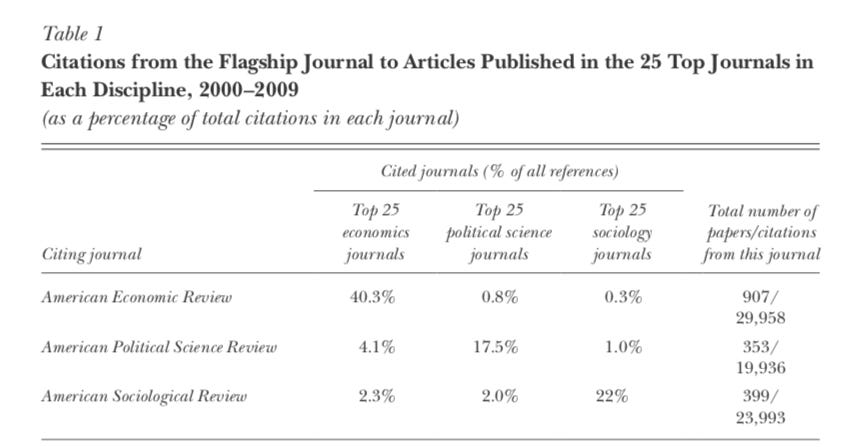

Furthermore, they looked at top papers from political science, economics and sociology. They found that political science and sociology cited economics papers many times more than the other way around:

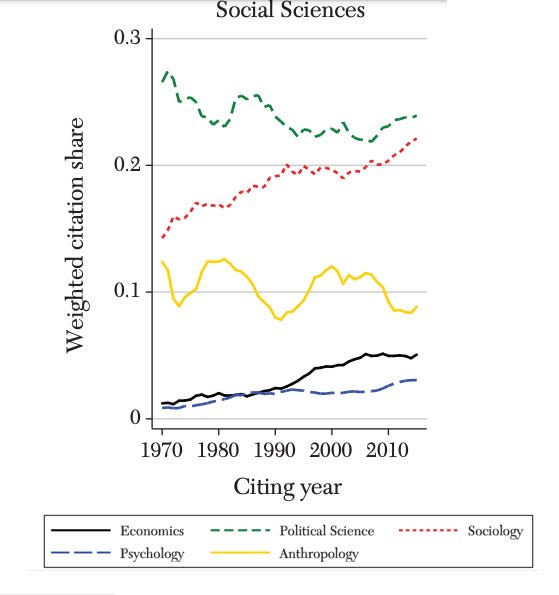

This lack of citing other social sciences was later confirmed by Angrist et al:

Given the complex interdisciplinary nature of societal issues, studying the basics of economics might make you overconfident that you can solve societal problems.

Take, for example, supply and demand. The standard supply and demand model will tell you that having/increasing the minimum wage will automatically increase unemployment. But if we look at actual empirical evidence it shows us that it doesn't. Overrelying on simple economic models might mislead us about which policies will actually help people, while a more holistic look at the social sciences as a whole may counter that.

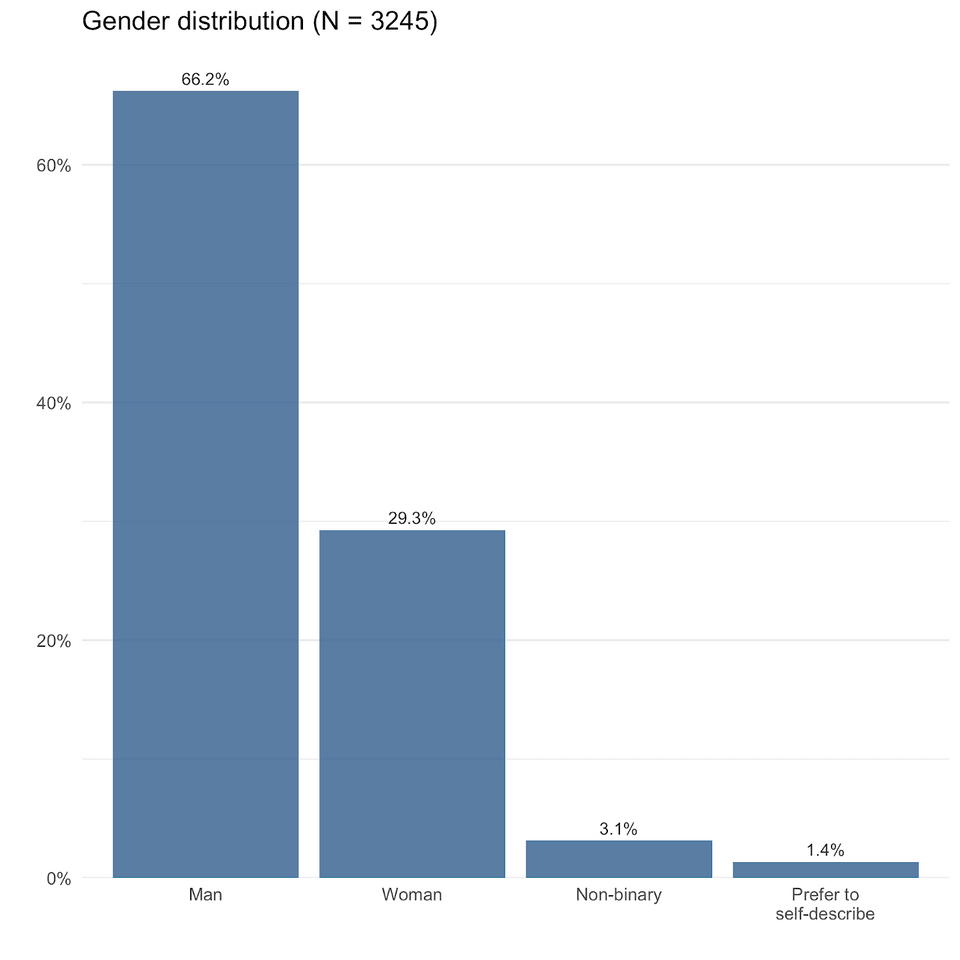

Furthermore, by focusing our recruitment on only a couple disciplines, we inherit the demographic problems of those disciplines. It is no wonder then that, just like the EA community, economics is also very homogeneous. Only 29% of the EA community are women:

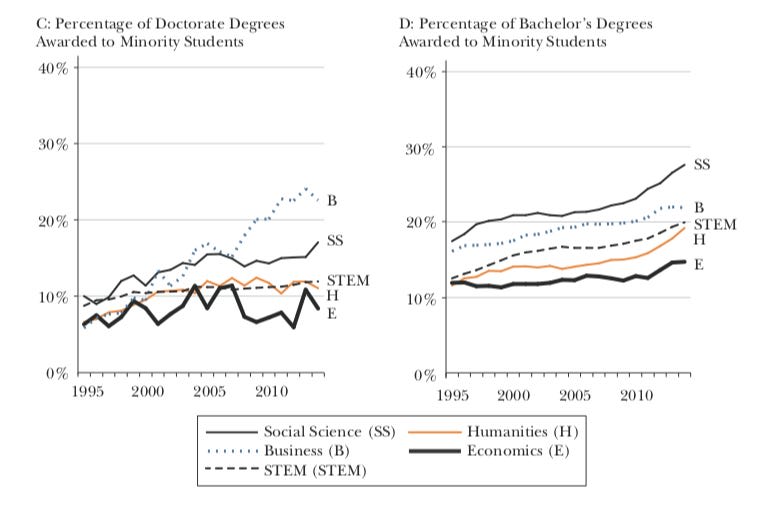

Bayer and Rouse show us that minorities are given fewer degrees in economics than other disciplines:

As are women:

They also get only 13.7% of the authorship of economics papers, are less likely to get tenure in their first academic job compared to men, and face a lot of discrimination in general. An AEA survey found that half of women say they were treated unfairly because of their sex and almost half say they've avoided conferences/seminars out of fear of harassment.

If we look at the other two popular disciplines in EA, philosophy and computer science, we’ll see that they have similar issues with underrepresentation and discrimination.

If we want to avoid these issues, I suggest we start reading and recruiting more from other disciplines too.

Apologies if this is already covered in the citations you linked somewhere, but I don't think the chart/graph you posted is direct evidence that economics is more insular than other fields. There are more economists (and psychologists!) than anthropologists and political scientists[1], so if you assume citations are a random graph[2] with a penalty across disciplines that decreases with time, you might get something similar to the current observed data, without any meaningful differences in field in propensity to cite .

Now I haven't done the analysis myself so maybe you still see bias after controlling for that, but I think this is such an obvious thing you should control for that I'm skeptical of any analysis without such controls.

I also think "minorities are given fewer degrees in economics than other disciplines" is a weird gloss for the Bayer and Rouse data, since their definition of "minority" inexplicably do not include Asians!

For example, a quick Google search suggests ~6200 political scientists and ~35,000 economists in the US, which is a very similar to eyeballing the ratios you posted.

In the extreme, imagine if there's 10,000 economists and 10 philologists. Obviously the philologists are individually much more likely to cite economists than vice versa! So that alone can drive the ratio differences, even if the philologists actually have lower cross-disciplinary willingness to cite than the economists!

The first (by Fourcade et al) is about percentage not absolute numbers, so this is direct evidence of economists preferring to stay insular. Same for the one about citations in flagship journals. We can see that both the number of papers and the number of citations in economics is indeed higher, however it's so minor (still within the same order of magnitude), while the differences are so large (more than an order of magnitude) that the trend still remains. Similar for the Angris et al one (also, I don't know where you got these numbers from... the bureau of labor statistics indeed says 6,200 political scientists, but only 17,500 economists, so that ratio is not enough to explain the gap).

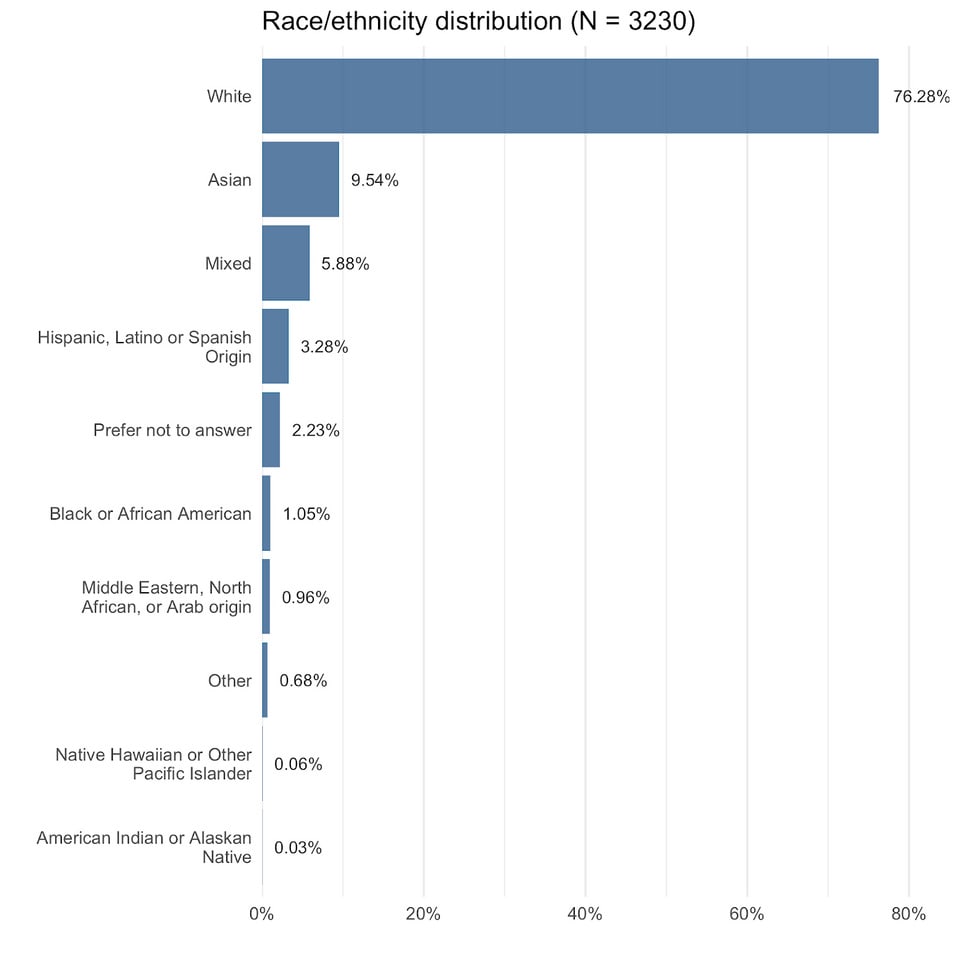

I'm more worried about black and other minorities within EA, since, again looking at the EA demographics data, Asians do comparatively better (comparatively being a load-bearing term there), while black and brown people do not (maybe also inherited from economics?). When we look at the race scandals in EA (Bostrom scandal, Manifest scandal, FLI scandal...) it's always about black and brown people being called less-intelligent, not Asians. So I think that's where our focus should be.

The source was DataUSA; I didn't look too carefully and I'm happy to agree that BLS is a better source.

Suppose there are 1000 economists in the world and only 2 political scientists. Would you agree that if a higher percentage of political scientists' citations were of economists than economists citing political scientists, it's not evidence of economists being more insular?

If it was literally 2 we couldn't do statistics, but say it was the same ratio but one we could do statistics on, e.g. 1000.000 vs 2000, I would say this research is valid. If it was just about citations it would be a problem, but what's being polled there is opinions on interdisciplinary research, so it's about attitude towards working with other disciplines in general.

If a higher percentage of (a quantitatively smaller number of) political scientists think working with other disciplines is better, whereas a lower percentage of (a quantitatively higher number of) economists think so, then even though there is (in absolute numbers) a higher quantity of economists who think that interdisciplinary research is better, we can still (comparatively) say that economists are more in favor of being insular than political scientists.

I agree about attitudes, I was referring to citations.

I ended up doing some of my own empirics here. See my comment below in response to David.

I am beginning to see what Linch is saying. The actual hard question here is - What is the appropriate counterfactual to EA? EA is more insular compared to what exactly? Bob says compare the state of Econ against the state of EA but is that fair? I wrote some more initial thoughts down in my Github repo along with some R/Python code.

I can't believe my first instinct was to think about the comparison group. But I got there and better late than never!

Haha thanks! Honestly I think you contributed much more to the discussion than I did! No need to say "I am beginning to see what Linch is saying." I think you were answering a different question!

Ilan and Shakked Noy have a nice piece on one aspect of this, "The Short-Termism of ‘Hard’ Economics." It's forthcoming in Essays on longtermism, hopefully within a month or two. They argue that preferences for methodological hardness in economics make it difficult to publish longtermist research within economics.

To be fair, economics as a field is widely regarded as one of the strongest and most successful in academia right now. There are definitely challenges, of which Bob and the Noy's identify some, but I don't want to give the impression that academics are too down on economics as a field. They've been killing it since the mid-20th century.

I also don't think economists are crazy to think that their top journals are sometimes more rigorous than leading interdisciplinary journals, which can be a bit more headline-chasing and often don't give authors enough words to be fully rigorous.

I don't see how this can possible be a knock on economics as a field (even if we grant for the sake of argument your somewhat selective citing of the academic literature here) since your sources for the 'actual empirical evidence' are economics papers published by economists in economics journals. It looks like you, like other social scientists, agree that the gold standard for 'actual empirical evidence' on social questions is citations to economics papers.

I'm not knocking economics as a field otherwise I wouldn't study/write about economics, I'm knocking overrelying on simple economic models to the detriment of a complete picture. That's why I cite evidence of simple economic models failing (which are obviously published in economic journals) and talk about the value that other disciplines can bring. If you think my citing is bad, perhaps you'd like to present some better sources?

I loved this critique and sympathize with it. As somebody studying Public Policy which requires interfacing with all the different social science departments in my university, I empathize with what you mean by the "insularity" of the economics department!

But I think you are missing a bigger critique here. It is that EA philosophy has a lack of rigor stemming from an intrinsic insularity that is not inherited from elsewhere. If anything, EA has to start acknowledging ideas from other disciplines and not reinvent the wheel! This includes acknowledging economics, and as you rightly say, other humanities. In fact, this opinion is shared by an economist - Tyler Cowen. See his critique of Parfit's 'On What Matters?' (Link to article). My reading of his critique is that Parfit (who planted the seeds for EA philosophy) was too much of a philosopher to his own detriment! He couldn't engage with scholars from other disciplines to see the progress already made on many of the questions he was interested in.

Overall, I agree with you that EA philosophy must engage widely with ideas from outside. But I disagree that this is a problem it inherited from economics. I think this is intrinsic to EA philosophy due to the circumstances in which it was born (i.e.) an academic sitting in some cabin in the woods. That is why I don't find it appealing at all when EA people plan to live together with other EAs or date other EAs or find employment only in EA-aligned organizations. This is altogether to the detriment of EA evolving into new areas and X risks! To me the best EA people are ones who know of EA philosophy but engage with it only once in a while to check in and see what's going on. These are the folks who will act as bridges that will ultimately make EA philosophy much better. We don't post as much or come to all the events but we come when we feel the need to!

In my own head, the way I deal with this is, is to create a distinction between "Parfitianism" and "EA". "Parfitianism" is done and it is a good starting point for us to learn from. But to build "EA" we need to engage mostly outside of EA philosophy, as you rightly say, and start building something better. In fact, I think Parfit himself believed in something like this, when he concluded Reasons and Persons with a section titled, "How both human history, and the history of ethics, may be just beginning"

I probably won't read another post on the forum for a while. Out of the stuff that is currently on the forum this was the one worth reading. Good post!

I think it's a bit misleading to say EA philosophy "lacks rigor", because it could be taken to imply it falls below some sort of known disciplinary standard of reasoning/evidence that at least some other philosophy reaches. I don't think this is even close to being true. EA philosophy to me means mostly "Bostrom, Ord and MacAskill's academic papers, and stuff that came out of the Global Priorities Institute". And that stuff has been published in very good journals over and over again. Even MIRI's unorthodox ideas about decision theory have been written-up and published in a very good philosophy journal! EA philosophy is about as academically mainstream as philosophy gets. It's true a large majority of academic philosophers disagree with at least some of it, but that is also true of any comparable rival body of philosophical work.

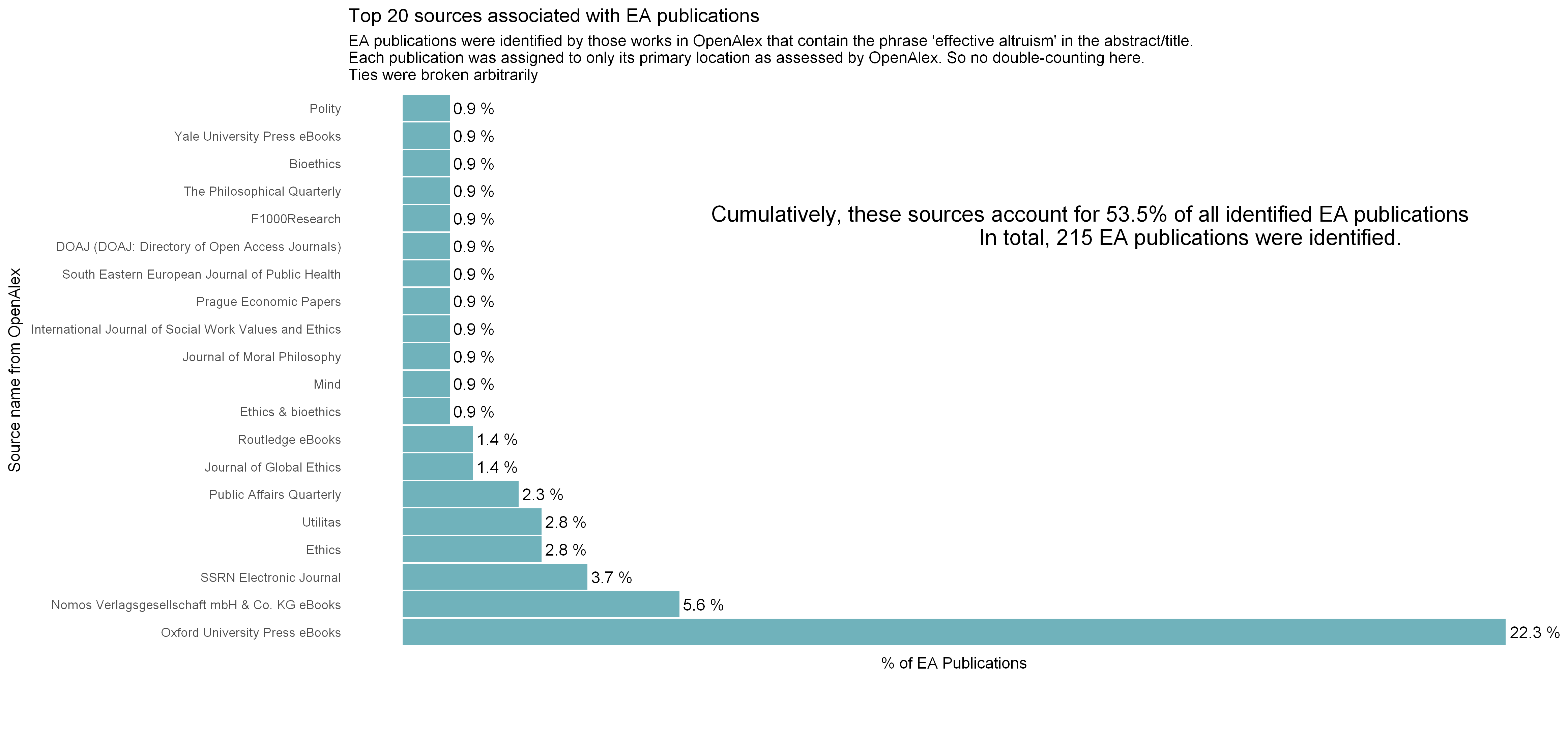

Great comment David! It made me focus in on the heart of the question here. It is simply this - What is the right counterfactual to EA, the philosophy/academic discipline? OP is comparing EA philosophy/discipline to Econ. But is that fair? When I read your comment this morning, I noticed how I utterly failed to clarify that EA is less rigorous... than what?! It got me thinking empirically and I quickly whipped up some stuff using OpenAlex which is a open-source repository of publications used by bibliometricians. Now this preliminary analysis I show doesn't resolve the question of what is counterfactual to EA, but it begins to describe the problem better.

If you're interested, see my GitHub repo with more details on the research design that I imagined and the Python/R code. I wonder if OP will like this because I'm doing stuff that a (design-based) econometrician would do :-)

First up, lets validate what David said makes sense - Are EA publications in top journals?

Yep. David is not wrong. But of course that is not the question! The claim I want to make is that EA publications are more insular than other stuff and the obstacle to making this claim is what the hell is "other stuff"?! This is where OpenAlex topics come in. OpenAlex uses a clsutering+classification pipeline to classify papers as belonging to some topic. Here is a plot showing that:

Now, the next step would be to ask ourselves, "EA has such a spread of topics. But field X has a much wider spread. This is why EA is insular" But what is that field X? EA compared to Deontology? Utilitarianism? These have around for decades - how is that a fair comparison group? What exactly is the benchmark to weigh EA, the discipline, against?

Now maybe the way to do this, is to pull out all the papers in these topics I have plotted above from OpenAlex and compare against those. But I guess a better way to do this would be to pull out abstracts of all publications, clean up, tokenize, cluster and see whats close by and compare against that. Can someone else make this pipeline more concrete?

EDIT: Fixed broken links

You may be interested in Siobhan's classic 2022 post Learning from non-EAs who seek to do good.

"Given the complex interdisciplinary nature of societal issues, studying the basics of economics might make you overconfident that you can solve societal problems.

Take, for example, supply and demand. The standard supply and demand model will tell you that having/increasing the minimum wage will automatically increase unemployment. But if we look at actual empirical evidence it shows us that it doesn't. Overrelying on simple economic models might mislead us about which policies will actually help people, while a more holistic look at the social sciences as a whole may counter that."

I disagree with this paragraph. Economists are trained to NOT stay at the basics of economics and NOT overrely on simple economic models. They develop more complex models. I rather have the impression that many people in other social science fields, when they deal with economics issues, rely too much on basic economics with its overly simplified models.

Note that economists - not sociologists, psychologists or anthropologists - came up with the empirical evidence that minimum wages barely increase unemployment. All your references are published in economics journals. And note that economists - not sociologists, psychologists or anthropologists - developed more complex models that explain why the competitive market equilibrium model with labor supply and demand was too simplistic.

This post is too meta, in my opinion. The key reason EA discusses economics a lot more is that if you want to have true beliefs about how to improve the world, economics can provide a bunch more useful insights than other parts of the social sciences. If you want to critique this, you need to engage with the actual object level claims of how useful the fields are, how good their scientific standards are and how much value there actually is. And I didn't feel like your post spent much time arguing for this

Source?

EDIT: I'm getting downvoted for asking for a source on a controversial claim? Why? Why does the heterodox EA have to cite dozens of academic sources and still get more downvotes than someone just asserting an academically controversial (but orthodox within EA) claim without a citation or justification? Why does asking for one generate downvotes?

My null hypothesis is that any research field is not particularly useful until proven otherwise. I am certainly not claiming that all economics research is high quality, but I've seen some examples that seemed pretty legit to me. For example, RCTs on direct cash transfers seem pretty useful and relevant to EA goals. And I think tools like RCTs are a pretty powerful way to find true insights into complex questions.

I largely haven't come across insights from other social sciences that seem useful for EA interests. I haven't investigated this much, and I would be happily convinced otherwise, but a lot of the stuff I've seen doesn't seem like it is tracking truth. You're the one writing a post trying to convince people of the claim that there is useful content here. I didn't see evidence of this in your post though I may have missed something. If you have some in mind I would be interested in seeing it.

(I didn't downvote you, and don't endorse people doing that)

Thanks for the comment, that seems like a strange null hypothesis to me but alright. My earlier aversion to commenting on the EA forum has borne out again, so I'm going to stop commenting now.

The papers you cite about how the minimum wage doesn't lead to a negative impact on jobs all seem like economics papers to me. What are the social science papers you have in mind that provide useful evidence that the minimum wage doesn't harm employment?

I've already responded to Larks on this