This is a linkpost for https://benjamintodd.substack.com/p/the-market-expects-ai-software-to

We can use Nvidia's stock price to estimate plausible market expectations for the size of the AI chip market, and we can use that to back-out expectations about AI software revenues and value creation.

Doing this helps to understand how much AI growth is expected by society, and how EA expectations compare. It's similar to an earlier post that uses interest rates in a similar way, except I'd argue using the prices of AI companies is more useful right now, since it's more targeted at the figures we most care about.

The exercise requires making some assumptions which I think are plausible (but not guaranteed to hold).

The full analysis is here, but here are some key points:

- Nvidia’s current market cap implies the future AI chip market reaches over ~$180bn/year (at current margins), then grows at average rates after that (so around $200bn by 2027). If margins or market share decline, revenues need to be even higher.

- For a data centre to actually use these chips in servers costs another ~80% for other hardware and electricity, then the AI software company that rents the chips will typically have at least another 40% in labour costs.

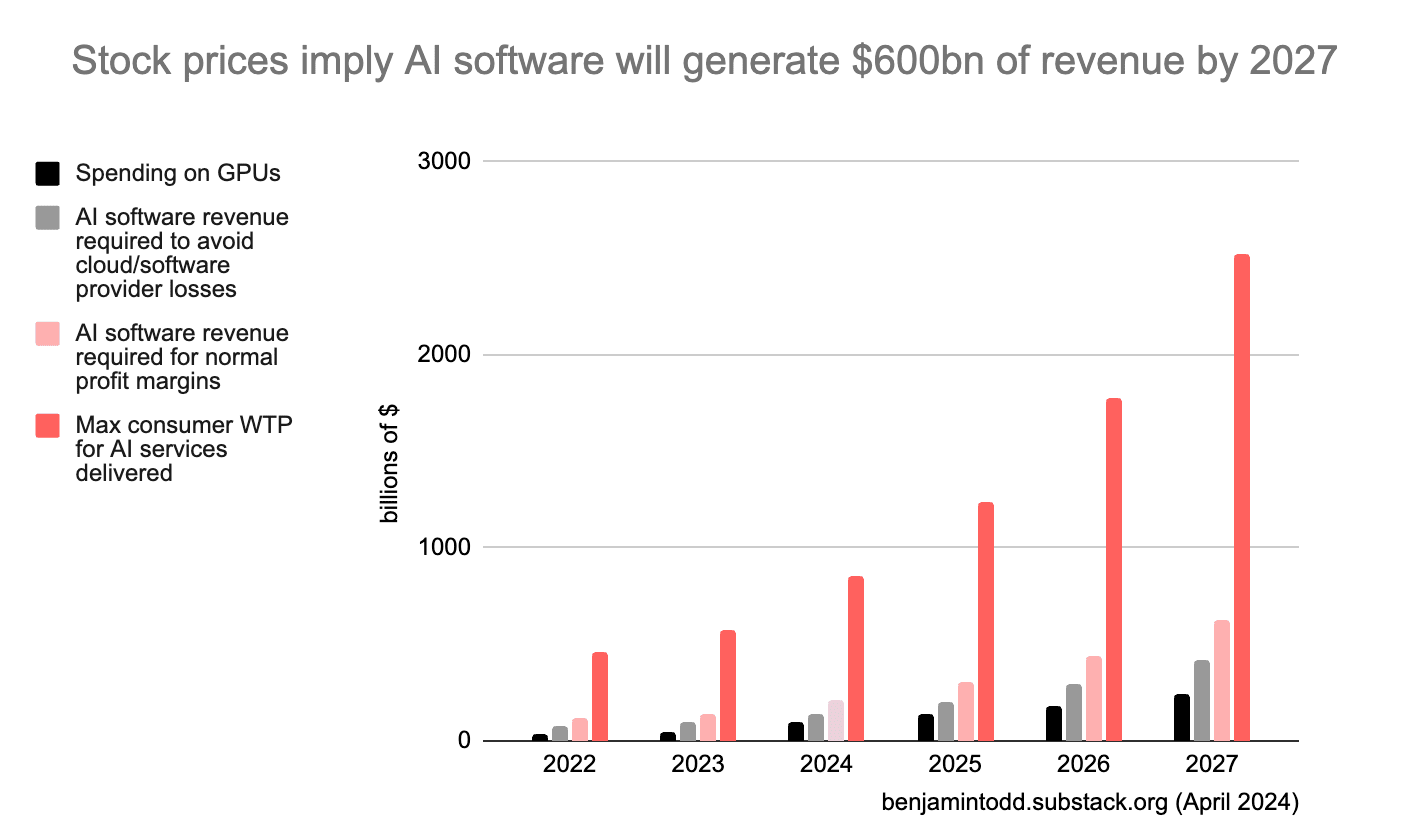

- This means with $200bn/year spent on AI chips, AI software revenues need reach $500bn/year for these groups to avoid losses, or $800bn/year to make normal profit margins. That would likely require consumers to be willing to pay up to several trillion for these services.

- The typical lifetime of a GPU implies that revenues would need to reach these levels before 2028. If you made a simple model with 35% annual growth in GPU spending, you can estimate year-by-year revenues, as shown in the chart below.

- This isn’t just about Nvidia – other estimates (e.g. the price of Microsoft) seem consistent with these figures.

- These revenues seem high in that they require a big scale up from today; but low if you think AI could start to automate a large fraction of jobs before 2030.

- If market expectations are correct, then by 2027 the amount of money generated by AI will make it easy to fund $10bn+ training runs.

Thanks, Ben, for writing this up! I very much enjoyed reading your intuition.

I was a bit confused in a few places with your reasoning (but to be fair, I didn't read your article super carefully).

Thanks, Ben! I enjoyed reading your write-up and appreciate your thought experiment.

Hi Wayne,

Those are good comments!

On the timing of the profits, my first estimate is for how far profits will need to eventually rise.

To estimate the year-by-year figures, I just assume revenues grow at the 5yr average rate of ~35% and check that's roughly in line with analyst expectations. That's a further extrapolation, but I found it helpful to get a sense of a specific plausible scenario.

(I also think that if Nvidia revenue looked to be under <20% p.a. the next few quarters, the stock would sell off, though that's just a judgement call.)

On the discount rate, my initial estimate is for the increase in earnings for Nvidia relative to other companies (which allows us to roughly factor out the average market discount rate) and assuming that Nvidia is roughly as risky as other companies.

In the appendix I discuss how if Nvidia is riskier than other companies it could change the estimate. Using Nvidia's beta as an estimate of the riskiness doesn't seem to result in a big change to the bottom line.

I agree analyst expectations are a worse guide than market prices, which is why I tried to focus on market prices wherever possible.

The GPU lifespan figures come in when going from GPU spending to software revenues. (They're not used for Nvidia's valuation.)

If $100bn is spent on GPUs this year, then you can amortise that cost over the GPU's lifespan.

A 4 year lifespan would mean data centre companies need to earn at least $25bn of revenues per year for the next 4 years to cover those capital costs. (And then more to pay for the other hardware and electricity they need, as well as profit.)

On consumer value, I was unsure whether to just focus on revenues or make this extra leap. The reason I was interested in it is I wanted to get a more intuitive sense of the scale of the economic value AI software would need to create, in terms that are closer to GDP, or % of work tasks automated, or consumer surplus.

Consumer value isn't a standard term, but if you subtract the cost of the AI software from it, you get consumer surplus (max WTP - price). Arguably the consumer surplus increase will be equal to the GDP increase. However, I got different advice on how to calculate the GDP increase, so I left it at consumer value.

I agree looking at more historical case studies of new technologies being introduced would be interesting. Thanks for the links!

You cannot derive revenue, or the shape of revenue growth, from a stock price. I think what you mean is consensus forecasts that support the current share price. The title of the article is provably incorrect.

Your objections seem reasonable but I do not understand their implications due to a lack of finance background. Would you mind helping me understand how your points affect the takeaway? Specifically, do you think that the estimates presented here are biased, much more uncertain than the post implies, or something else?

Sure, the claim hides a lot of uncertainties. At a high level the article says “A implies X, Y and Z”, but you can’t possibly derive all of that information from the single number A. Really what’s the article should say is “X, Y and Z are consistent with the value of A”, which is a very different claim.

i don’t specifically disagree with X, Y and Z.

Can you elaborate? The stock price tells us about the NPV of future profits, not revenue. However, if we use make an assumption about margin, that tells us something about future expected revenues.

I'm also not claiming to prove the claim. More that current market prices seem consistent with a scenario like this, and this scenario seems plausible for other reasons (though they could also be consistent with other scenarios).

I basically say this in the first sentence of the original post. I've edited the intro on the forum to make it clearer.

Perhaps you could say which additional assumptions in the original post you disagree with?

Your claim is very strong that “the market implies X”, when I think what you mean is that “the share price is consistent with X”.

There are a lot of assumptions stacked up:

I agree all these factors go into it (e.g. I discuss how it's not the same as the mean expectation in the appendix of the main post, and also the point about AI changing interest rates).

It's possible I should hedge more in the title of the post. That said, I think the broad conclusion actually holds up to plausible variation in many of these parameters.

For instance, margin is definitely a huge variable, but Nvidia's margin is already very high. More likely the margin falls, and that means the size of the chip market needs to be even bigger than the estimate.

I do think you should hedge more given the tower of assumptions underneath.

The title of the post is simultaneously very confident ("the market implies" and "but not more"), but also somewhat imprecise ("trillions" and "value"). It was not clear to me that the point you were trying to make was that the number was high.

Your use of "but not more" implies you were also trying to assert the point that it was not that high, but I agree with your point above that the market could be even bigger. If you believe it could be much bigger, that seems inconsistent with the title.

I also think "value" and "revenue" are not equivalent for 2 reasons:

FWIW this might not be true of the average reader but I felt like I understood all the implicit assumptions Ben was making and I think it's fine that he didn't add more caveats/hedging. His argument improved my model of the world.

It's fair that I only added "(but not more)" to the forum version – it's not in the original article which was framed more like a lower bound. Though, I stand by "not more" in the sense that the market isn't expecting it to be *way* more, as you'd get in an intelligence explosion or automation of most of the economy. Anyway I edited it a bit.

I'm not taking revenue to be equivalent to value. I define value as max consumer willingness to pay, which is closely related to consumer surplus.

I agree risk also comes into it – it's not a risk-neutral expected value (I discuss that in the final section of the OP).

Interesting suggestion that the Big 5 are riskier than Nvidia. I think that's not how the market sees it – the big 5 have lower price & earnings volatility and lower beta. Historically chips have been very cyclical. The market also seems to think there's a significant chance Nvidia loses market share to TPUs or AMD. I think the main reason Nvidia has a higher PE ratio is due its earnings growth.

As models are pushed into every computer-mediated online interaction, training costs will likely be dwarfed by inference costs. NVidia's market cap may therefore be misleading in terms of the potential magnitude of investment in inference infrastructure, as NVidia is not as well positioned for inference as it is currently for training. Furthermore, cloud-based AI inference requires low-latency network data centre (DC) access. Such availability will likely be severely curtailed by the electrical power density that is physically available for the scaling of AI inference. i.e. cheap electricity for AI compute is near nuclear and hydro power, and typically not near major conurbations, and suitable for AI training, but not for inference.

How would you factor in exponential growth specifically in AI inference? Do you think this will occur within the DC or in edge computing?

I suspect AI inference will be pushed to migrate to smartphones due to both latency requirements and significant data privacy concerns. If this migration is inevitable, it will likely drive a huge amount of innovation in low-power ASIC neural compute.

I don't get it. How are consumers supposed to pay trillions of dollars if AI is going to automate a large fraction of their jobs?

Not sure I follow. Current market expectations for AI is that AI WON'T automate a large fraction of jobs. Rather just that it'll produce value a few trillion dollars, which is only couple of percent of world GDP.

But even if AI does automate a lot of work, that doesn't mean everyone is suddenly poor. If AI is valuable, then GDP will grow, which means there's on net more money around to pay for AI software.

I misinterpreted "but low if you think AI could start to automate a large fraction of jobs before 2030". Thanks for clarifying :)

Ah makes sense! :)