This is crossposted from Medium. I've broken this into pieces there.

- The Structure of the EA Movement (Intro)

- Implications of the EA Ideology

- Flaws in the EA Community Structure

- Next Steps for EA

On my audience:

This report is for those who believe in ‘doing good better’. This includes Effective Altruists, but also academics, politicians, movement makers, idealists, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, and more: anyone who believes in the ideal that it is important to improve the world and that it is important to do so in effective ways.

Yet, there are many possible definitions for ‘good’, ‘better’, and even ‘doing’, each of which may lead to very different decisions and actions. However defined, I believe there is a shared spirit which underpins all these different groups: a humanistic, driven, hopeful yet realistic ethos that things can be better than they are. I write this report with that spirit in mind.

Two more notes: First, this report is a critical analysis. It's aim is to point out flaws in the EA movement's structure and tries explain why EA has faced many of the challenges it has. This report is not a wholistic one, nor a strategic one. It doesn't paint a complete picture of what EA is and does, nor does it focus on actionable steps or remedies. What is focused on here is understanding the causes of EA's problems. Indeed, most of the issues I point out do not seem to have very straightforward solutions, in part beacuse of their deep-rooted structural nature. Regrettably, I leave the task of deciding what to do next for future reports and to the reader.

Second, this report is also not written in the style of the EA Forum, and it may seem to unecessairly overexplains at times. Appologies to the EA reader. I do this with the intention of making the report more accessible, such that we can work together towards doing good better.

Executive Summary

EA’s Structure is Ineffective and Harmful

Effective Altruism (EA) is a social movement dedicated to acting on the question ‘how can we do good better? It is composed of a community of organizations and individuals who follow the EA ideology, or a set of ideas about ‘doing good better’. Under this ideology, EA devotes considerable resources to finding and acting on important, tractable, and neglected causes for improving the world. However, the EA movement has fallen short in its understanding and organization of its internal structure, which has led to inefficiencies and harm, to the peril of its community, itself, and the world. This report highlights some of those key structural failures.

A Utilitarian Ideology

The EA ideology, a set of moral ideas, values, and practices, includes problematic and harmful ideas. Specifically, the ideology ties morality to quantified impact which results in poor decision making, encourages ends justify the means reasoning, and disregards individuality, resulting in crippling responsibility on individuals and burnout. Notably, EA’s ideology gets its roots from and is strikingly similar to utilitarianism.

No Governance is Bad Governance

The EA community is a social community brought together by shared beliefs and practices about ‘doing good better’. The community lacks formal boundaries or governance structure, while power is concentrated with a few organizations and individuals, specifically the leadership of Open Philanthropy and the Center for Effective Altruism. The community is thus reliant on the judgement and actions of a select few to ensure the effectiveness and success of the movement, with little means to hold actors accountable. Yet, due to the informal nature of their power, many leaders have failed to take on crucial responsibilities, allowing dysfunctional community practices to go unchecked, resulting in persistent poor decision making and scandal.

Effective Altruism Needs Reform

Many of EA's failures can be explained by structural features of the movement, whether its utilitarian ideology or its imbalanced, poorly governed community. Recently, Ben West has recently suggested that EA is now in its ‘third wave’ (2023), facing a new internal and external environment that will require a new set of strategies and initiatives. Notably, there has been promising internal restructuring from Effective Ventures and the Center for Effective Altruism, although it is too soon to gauge their effectiveness. Yet, due to the movement’s structure, the community itself has very little ability to take action. For the movement itself, change must start from the top.

EA may be entering a new era. However, the structural issues detailed in this report havep plagued EA's good intentions and noble efforts throughout most of its history. Nor are they easy to fix, as their deep rooted nature means they are imbeded deep within the fabric of the movement. If EA wants to continue to work towards its goal of ‘doing good better’, EA must turn its focus inwards and work hard to create robust governance structures and candid assessments about it's beliefs and norms. Another path forward may be to absolve the movement.

The Structure of the Effective Altrusim Movement

In the late 2000s, Effective Altruism (EA) started as a question. It asked: “How can we do the most good?” In a world full of suffering, with limited time and resources, many found this question compelling, and spent a lot of time thinking hard about it. They wrote books and papers, establishing values and frameworks, leading to unintuitive but shocking answers. Yet, it wasn’t enough to theorize: their answers compelled action. Conferences were held in EA’s name, organizations were founded to direct resources, communities were formed and expanded. Almost overnight, Effective Altruism had become something bigger.

Today, Effective Altruism is still guided by the question ‘How can we do good better?’, but has also evolved into a complex network of organizations, individuals, ideas, values, and practices: a social movement. Throughout the years, the EA movement has made significant advances in exploring, understanding, and acting on effective ways to improve the world. However, the same rigour has not been applied to the movement itself.

This piece breaks down the structure of EA movement, and is an introduction to a series which critically analyzes the structure of the EA movement. The other pieces in the series are on the implications of the EA ideology, the flaws of the EA community structure, and some possible futures for the EA movement.[1]

What is Effective Altruism?

Within many discussions about EA, whether academic literature, in a discussion at the bar, or on the EA Forum, it is not immediately clear what ‘Effective Altruism’ is. For example, I have heard the term ‘EA’ to denote a philosophy, a community, a question, an ideology, an identity, or a social movement, often even switching between definitions in the same conversation. It begs the question: What exactly is Effective Altruism? Furthermore, how is Effective Altruism structured?

Here, I argue that EA is best understood as a social movement, made up of an ideology and a community. This section dives into the definitions and characteristics of each of these components, and how they come together to form the EA movement.

The EA Ideology

The EA ideology is a set of ideas and practices which the EA community follows. It provides a framework for thinking about the world, defining right and wrong, setting targets and constraints, and driving action.

As simply a set of ideas, the EA ideology is only as powerful as the community’s belief in and adherence to those ideas. The community may be structured around the ideology, but the ideology only exists insofar as someone believes in it. While the community is subject to the power of the ideology, it also holds the power to change or discard the ideology.

Defining the EA ideology has challenges. Notably, there is also no official EA ideology. While EA does have central texts — such as books, forum posts, or websites — none of them officially claim authority over the definition or principles of the movement. This structural choice has created constant discussion within the community over EA’s core ideas and practices, and allows for flexibility, and for regional or sectarian differences to emerge.

Yet, these differences are usually overcome by greater shared beliefs, as evidenced by a continued union of sometimes competing interests under the brand of ‘Effective Altruism’. The literature and discussion has also converged over the years, and EA’s core ideology has remained fairly constant over the last decade.

The EA Community

EA is also a community, composed of people who believe in the EA ideology. Note the circularity: the definition of the community hinges on one’s definition of ideology. The same person may be seen as a member of the community, adjacent to the community, or not at all part of the community depending on one’s definition of the ideology. As a result, the boundaries and ideals of the EA community are defined by mutual recognition and enforced socially, through the definition and debate over the EA ideology (Diani, 1992).

The EA community lacks formal membership criteria. Anyone can self-identify as part of the community, or start a project that has ‘Effective Altruism’ in the name (MacAskill, 2023). Yet, this does not mean the community has no boundaries, as both the community and broader society is able to impose social costs and expectations based on identity. Thus, while many identify as an ‘Effective Altruist’ or as an ‘EA’ many others identify as “EA-adjacent,” denoting agreement with certain EA values but resistance to fully embracing its underlying ideology. As identity is also socially imposed, there may also be instances where someone’s actions match the EA ideology, thus earning them the social reputation of being an Effective Altruist, while they do not think of themselves as such.

EA, the Social Movement

The EA social movement is composed of the EA community, which is both guided by and defines the EA ideology. In this way, EA can also be thought of as a distinct entity with unique traits and as an actor. For example, we can describe the movement, saying that EA places great value on evidence, or that it is utilitarian. We also attribute action to the movement, such as saying that EA advocates strongly for AI safety, or that EA believes that it isn’t utilitarian.

However, from a definition standpoint, seeing EA as a distinct entity also presents its challenges, as it isn’t exactly clear who and what is or isn’t EA. For example, is an organization that receives funding from an EA funder and works on an EA cause like AI Safety a part of EA? Does someone who hangs out in EA spaces but who doesn’t believe in EA ideas part of EA? What exactly are and aren’t EA beliefs? For various reasons, predominantly EA’s informal nature, these are all difficult, and in many cases, unanswerable questions, as the definition of EA itself is also susceptible to change. The nature of this difficulty is future explored in the ideology and community sections.

Thus, to talk about EA is to talk about EA precisely on the level of a social movement. While this social movement is made up of the interaction of its parts, the translation between levels is not linear; to attribute a trait to EA is not necessarily to attribute it to its parts, nor the other way around. For example, to say that EA is elitist or noble is not to say that this is necessarily true of its constituents. However, as EA is made of its parts, traits on the movement-level are also often reflective of the community and ideology, and vice versa.

Importantly, social movements have goals. As the civil rights movement’s goal is to end racial segregation and discrimination, or the anti-Vietnam War movement’s goal was to end the Vietnam war, I see the goal of the EA movement as implementing ways to do good better. This may look like conducting research on which initiatives are most effective or funnelling resources towards those effective initiatives. However it is done, we can judge the success of EA on the basis of its ability to accomplish this goal. Importantly, note how EA’s efforts towards this goal are contingent on its specific beliefs — EA’s ideology — and the way those in the community organize — EA’s community structure.

EA’s informally organized nature makes it difficult to describe and pinpoint. Like any complex system, it is constantly changing and adapting, taking on new elements and discarding old ones. While imperfect, seeing the movement as a community bound together by a self-created ideology provides a level of structure such that we can more rigorously analyze each of these components, and understand their role in shaping the strengths and flaws and successes and failures of the Effective Altruism movement.

--

The Effective Altrusim Ideology

The Consequences of Taking Utilitarianism Seriously

The EA Ideology

The EA ideology is a driving force for the movement, derived largely from the community’s pursuit of the question ‘How can we do good better?’. The ideology consists of the beliefs of the community, thus guiding its actions, through setting standards, expectations, goals, and values. While it should be noted that the subtleties of ideologies are often in flux as people’s beliefs change, in the case of EA, there are longstanding ideas we can point to, which have long guided the movement and had significant influence on the movement’s impact and effectiveness.

Origins of the Ideology

One key source of the EA ideology is the philosophy of Peter Singer, who is also an early and vocal advocate for EA. Through his drowning child thought experiment, Singer argued that if we have the means to do so, we have a moral obligation to reduce suffering, whether it is a child drowning in a fountain in front of you or someone halfway across the world (Singer, 1972). That is, we have a moral obligation to reduce suffering to the best of our ability, regardless of the cause or geographic location of the suffering. This idea has been translated into its inverse by EA: that we have a moral obligation to do good to the best of our ability, regardless of the cause or geographic location of the suffering.

Another core idea is that we should prioritize more impactful interventions. A classic EA example goes:

For example, suppose we want to help those who are blind. We can help blind people in a developed country like the United States by paying to train a guide dog. This is more expensive than most people realize and costs around $50,000 to train a dog and teach its recipient how to make best use of it. In contrast, there are millions of people in developing countries who remain blind for lack of a cheap and safe eye operation. For the same amount of money as training a single guide dog, we could completely cure enough people of Trachoma-induced blindness to prevent a total of 2,600 years of blindness. (Giving What We Can, 2012)

Even considering the benefits from the companionship of having a dog, EA argues that the benefit is less significantly less than the benefits from spending $50,000 on curing trachoma-induced blindnesses. Thus, to do good better, we should spend this money on trachoma-induced blindness.

When we combine this idea about cost-effectiveness, which tells us how we should do good, with Singer’s, which tells us who we have a moral obligation to, we reach the conclusion that we have a moral duty to improve the world as effectively as we can. In Singer’s words:

Effective altruism is based on a very simple idea: we should do the most good we can. Obeying the usual rules about not stealing, cheating, hurting, and killing is not enough, or at least not enough for those of us who have the good fortune to live in material comfort, who can feed, house, and clothe ourselves and our families and still have money or time to spare. Living a minimally acceptable ethical life involves using a substantial part of our spare resources to make the world a better place. Living a fully ethical life involves doing the most good we can (Emphasis mine; Singer, 2015).

Looking at the history of EA, we can see how these ideas have informed its decision making. One example is the lifestyle of William MacAskill, a founder of EA and philosopher. A 2022 New Yorker profile described how, understanding how much impact his money can have, “MacAskill limits his personal budget to about twenty-six thousand pounds a year, and gives everything else away.” (Gideon Lewis-Kraus, 2022) Similarly, in 2009, Toby Orb founded Giving What We Can, which asks individuals to dedicate 10% of their lifetime earnings to charity. Ben Todd and William McAskill also founded 80,000 Hours in 2011, to help individuals have more impactful careers.

Importantly, EA’s answers are far from the only possible answers to the question ‘How can we do good better?’ Although to varying degrees of explicit adherence to this question, many other movements have been driven by the same questions, although with different ideologies and therefore paths. Examples include:

- Effective Philanthropy movement, who believe that when doing good, we should prioritize those geographically close to us, such as our friends, family, and immediate community.

- The collaborative funds and trust-based movement in philanthropy, which believes that most problems are wicked, so we should trust local stakeholders to know best.

- The Salvation Army, whose motto reads “Doing the Most Good”.

Should EA have followed any of these other beliefs, it would likely have gone down a very different path. In this sense, it is far from the first group of people to ask and answer this question, nor will they be the last.

An Intentionally Undefined Ideology

Yet, it is not exactly clear whether EA has an ideology. In what has become a core ideological text for EA, Helen Toner argues that “Effective Altruism is a Question (not an ideology)”, and that the claims and conclusions made by EA shouldn’t be seen as core parts of the movement (2014). Similarly, MacAskill argues that EA is a project, not a normative claim, meaning it is “consistent with any moral view” (2019). Both Toner and MacAskill argue that this ambiguity is intentional, allowing for a diversity of viewpoints to exist within EA, benefiting collaboration and preventing overconfidence. These views and beliefs are widely cited throughout the EA forum, and held within the community.

Yet, EA clearly and consistently privileges some viewpoints over others, as it must do when allocating funds or choosing operating values. So who is right? It is thus useful to return to the definition of an ideology — the set of ideas which guides the actions of a group. While Toner may be correct that EA as a whole is not an ideology — it is instead a social movement — all social movements are driven by ideologies, whether it is made explicit or not. Similarly, MacAskill’s idea of EA as a project might be analogous to EA as a movement, although we can see that this project still clearly has an ideology.

This is also clear from the experiences of many members. EA Forum user James Fodor posted a reply to Toner arguing “Effective Altruism is an Ideology, not (just) a Question” (Fodor, 2019). Similarly, user Siobhan_M has argued that EA is “a community based around ideology”, and ColdButtonIssues has discussed EA’s penumbra — “a set of ideas that aren’t implied by [EA] but nevertheless are widely shared” (Siobhan_M, 2022; ColdButtonIssues, 2022). Given the view’s prominence, we might even say that part of EA’s ideology is that it doesn’t have an ideology.

The False Promise of Neutrality

Thus, while not all of EA may accept it, the community has and is driven by a set of ideas about how to act and think about the world. While this ideological neutrality does have benefits, it also has disadvantages. For one, by actively denying the presence and impact of its ideology, EA limits its ability to understand itself.

The stance of not taking a stance also creates danger in itself, perhaps captured best through Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance, stating that “a truly tolerant society must retain the right to deny tolerance to those who promote intolerance” (1945). Should EA value neutrality, it must ensure it does not stay neutral in the face of immoral or abhorrent ideas.

Indeed, in his “non-normative” definition of EA, MacAskill does reject certain normative views, specifically “partialist views on which, for example, the wellbeing of one’s co-nationals count for more than those of foreigners and excludes non-welfarist views on which, for example, biodiversity or art has intrinsic value.” (2019) Yet, MacAskill only states this claim as ‘tentative’. Nor, given the emphasis on ecumenicalism, it is not clear from MacAskill’s definition that EA must not endorse morally tenuous views such as racial supremacy, terrorism, or slavery.

Should EA strive to be the moral leader it aspires to be in the world, it must have the courage to take stronger ideological and moral stances, and ensure immoral acts are not tolerated within its own community. In the words of philosopher Agnes Callard:

Neutrality may be an improvement over capitulating to the pressure to make moral proclamations in the absence of the corresponding moral knowledge, but that is a low bar. Neutrality describes how you act when you are ignorant on a matter that you, as a leader, really ought to have knowledge about, and you acknowledge this rather than pretending otherwise (2024).

EA and Utilitarianism

Officially, EA has made it clear that it is not utilitarian. MacAskill states as the first misconception of Effective Altruism, arguing that unlike utilitarianism, EA makes no claims about obligations of benevolence, does not agree that the ends justify the means, and does not claim that the good equals the sum total of wellbeing (2019). This sentiment has equally been echoed by other influential figures, including Ben Todd, founder of 80,000 hours, and philosopher and blogger Richard Yetter Chappell. More recently, partly in response to the FTX scandal, senior EAs Toby Ord and Rob Wilbins have also acknowledged the philosophy’s influence, but argue that EA has taken the good parts of utilitarianism, scrapping the harmful or controversial parts (2023).

Yet, EA has clear and strong utilitarian influences. For one, Peter Singer who played a significant role in shaping the ideas of the movement is one of the most prominent utilitarians alive. Many have also noted the strong utilitarian overtones in the writings of MacAskill and Ord, arguably the two most influential EA philosophers. For example, MacAskill is an author of “An Introduction to Utilitarianism”, and is listed often on the website ‘utilitarianism.net’.

Most strikingly, the EA community itself is heavily utilitarian, with 69.6% of respondents of 2019 EA survey identifying with utilitarianism, another 11.1% identifying with non-utilitarian consequentialism (Neil_Dullaghan, 2019). The EA community itself also had origins within utilitarian communities, such as Felicifia, a utilitarianism discussion forum, the EA Forum Wiki stating that “[Felicifia] hosted discussions, by contributors such as Toby Ord, Carl Shulman, and Brian Tomasik, about many ideas that would later become a core part of effective altruism” (n.d.).

Ultimately, this utilitarian influence has had a significant impact on EA’s decision-making and impact. Looking at EA’s history can show us strong and in many cases negative influence from utilitarian ideas. There are three main ideas of note: that impact is quantifiable, that we should maximize impact, and that we are responsible for doing good.

Perils in Quantifying Impact

One key idea in the EA ideology is scope sensitivity: that we should prioritize actions that have greater benefits. This idea aligns with utilitarianism, which quantifies morality through maximizing ‘utils’. Quantification works effectively for easily measurable phenomena, such as comparing malaria interventions through randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Yet, other phenomena are much harder to quantify, such as the ‘goodness’ of a political regime shift, or comparing the benefit from a concert vs that of a dinner out.

Thinking about values in quantities can be useful when numbers translate clearly into real-world outcomes, but they can also be misleading in situations where there is uncertainty or complexity, leaving us to rely on estimates and approximations. In such situations, numbers can also be used to deceive and mislead. Such calculations can also justify extreme actions, such as bombings or gambling the fate of humanity on a coin toss. One hyperbolized anecdote goes:

[A student] lent one of the most vocal advocates for effective altruism her toaster while they were both graduate students at Oxford. She reminded him to return it a week later, and a month later, and three months later, to no avail. Finally, invited to his apartment for a social gathering, she spotted the toaster on the kitchen counter, covered in mold.

“Why on earth didn’t you return the toaster to me?” she asked, in frustration.

“I ran the numbers,” he responded. “If I want to do good for the world, my time is better spent working on my thesis.”

“Couldn’t you at least have cleaned the damn thing?”

“From a moral point of view, I’m pretty sure the answer is no.” (Mounk, 2024)

This admittedly made-up example shows how relying on quantifying impact can justify socially unacceptable actions. What is also clear is that the effectiveness of quantifying impact is contingent on one’s ability to accurately make calculations, particularly in complex situations. While the time it would cost to return the toaster might indeed be better spent working on one’s thesis, potentially improving the world in the process, the cost to one’s social reputation and to the social fabric may very well out-weigh this benefit.

One historic example of a poorly-made and consequential decision justified through numbers is EA’s treatment of the purchase of Wytham Abbey. The estate is a 18-bedroom manor near Oxford built in 1480, complete with library, cinema room, swimming pool, and separate butler’s house. The Times described it in 1991 as “one of the loveliest houses in England” (Savills, n.d.), and was purchased for 15 million pounds in 2022 by the Effective Ventures Foundation with the purpose of hosting conferences and events. Summarizing the reaction to the purchase, EA Forum Nikos wrote: “To many, Wytham Abbey looked somewhat more luxurious and expensive than strictly necessary for an event location… [P]ublic perception isn’t quite what one might have hoped for. Even among EAs, the purchase seems to have left some (many?) with mixed feelings.” (2023).

The most official and complete justification by CEA for this purchase comes in the form of a comment on an EA forum post which questioned the purchase. Here, Owen Cotton-Barratt, who led the purchase, explains that “[t]he main case for the project was not a cost-saving one, but that if it was a success it could generate many more valuable workshops than would otherwise exist.” (2022) That is, having a dedicated venue near Oxford, where the EA community is strong, would allow for more specialized conferences to be hosted, for less effort and time. Cotton-Barratt goes on to include further considerations, such as financial and why they landed on Wytham Abbey in particular. He concludes that:

I did feel a little nervous about the optical effects, but think it’s better to let decisions be guided less by what we think looks good, and more by what we think is good — ultimately this was a decision I felt happy to defend. (2022)

Summarizing, Cotton-Barratt makes the argument that 15 million pounds spent on an event space is an effective use of resources. Although it is not stated, we might also assume that this purchase is seen to be more effective than spending the money on global poverty, climate change, or even building the EA movement. However, with EA always having the option to resell the property, and having a surplus of funds at the time, the purchase doesn’t seem all that unreasonable.

Yet, while Cotton-Barratt does state he considered the optical effects, it does not appear his calculations were accurate, nor did he consider the importance of communication about the purchase, particularly after EA’s reputation and community trust were already low after the FTX scandal. Particularly given the lack of communication about the purchase, an accurate impact driven decision might have calculated that the damage to EA’s reputation and community’s trust outweigh any benefits of making such a purchase or keeping it quiet. While we can only speculate what motivations drove Cotton-Barratt’s decision making, it is clear that EA allowed quantified decision making to cloud its judgement.

The Perils of Maximization

Another problematic idea within EA’s ideology is the focus on maximization. For example, Singer’s 2015 book on EA is titled “The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically”. The Center For Effective Altruism defines the goal of EA as “benefit[ing] others as much as possible” (n.d.). Similarly MacAskill writes: “effective altruists aim to maximise the wellbeing of all” (2017).

This focus is again reminiscent of utilitarianism, which sets no limit on the extent to which individuals have an obligation to increase utility, also a common point of critique for the philosophy. For example, if our goal is to maximize wealth or time spent with family, it is unclear at what point we should stop, as we would inevitably run into conflict with other objectives and hit diminishing returns.

The success of this maximization function is also highly dependent on the rigour and inclusivity of one’s definition of good, whether it be a general sense of ‘welfare’ or the operationalized QALYs. As our top priority is to maximize this quantity, anything which is not captured by the definition becomes a secondary concern. For example, MacAskill’s 2019 definition of good according to EA excluded art.

Maximization also necessarily entails being able to rank causes ordinally, which creates challenges when thinking about more qualitative and complex variables. Harder to measure outcomes like the quality of one’s relationships or the meaningfulness of one’s own life might also become secondary.

Furthermore, in trying to maximize a quantity, the distribution of the target also becomes secondary. For example, whether that utility is distributed evenly across individuals or concentrated within a small group is irrelevant, as long as the total quantity of utility is equal. This leads to situations where we are obliged to direct all resources towards those who receive more utility per unit — utility monsters — leaving little or none for everyone else. A reverse scenario is also possible, where we impose all suffering on a certain group in the name of maximizing the total quantity, such as that depicted in Ursula K LeGuin’s ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’.

The perils of maximization are familiar to EA. Sam Bankman-Fried was one of EA’s largest donors, and a touted example of EA’s idea of ‘earning to give’, where individuals seek high-income careers to donate substantial amounts to impactful causes. As one of EA’s biggest donors, Bankman-Fried was well connected within the EA community, such as being featured on the 80,000 hours website as an example of an impactful career, being personally recruited to EA by MacAskill, also employing many EAs at his companies. By 2022, Bankman-Fried had donated $140 million of his wealth to EA causes, and planned to do so with the remaining majority of his wealth. Bankman-Fried himself justified his extreme-wealth — at his peak he ranked 60th on the Forbes list of the world’s richest people — through the idea that he would use it to do good. For example, a widely-publicized FTX ad featuring a smiling Bankman-Fried read: “I’m in on crypto because I want to make the biggest global impact for good.”

This came to an end in late 2022, when it was revealed that Bankman-Fried had been engaging in fraud and money laundering, having illegally taken $10 billion dollars from customers of his crypto-trading platform FTX (U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of New York, 2022). One way SBF might have justified this is through the EA idea that he was earning to give. Given the scale of impact he might achieve with his money, financial fraud can be inconsequential and even justified should he expect it to help him achieve a bigger impact. Dylan Matthews, a journalist who has long covered EA, writes:

It looks increasingly likely that Sam Bankman-Fried appears to have engaged in extreme misconduct precisely because he believed in utilitarianism and effective altruism, and that his mostly EA-affiliated colleagues at FTX and Alameda Research went along with the plan for the same reasons. (2022)

In the aftermath of the scandal, many EAs condemned Bankman-Fried’s actions. In a Twitter post following the scandal, MacAskill reaffirms how he had long opposed “ends justify the means” thinking, bringing up similar statements from other EA leaders, including Holden Karnofsky, Toby Ord, and the Center for Effective Altruism (2022).

However it is not clear that EA has always taken this strong stance against maximization. Holden Karnofsky, founder of Open Philanthropy, wrote a forum post just months before Bankman-Fried’s fraud was revealed, saying:

EA is about maximizing how much good we do. What does that mean? None of us really knows. EA is about maximizing a property of the world that we’re conceptually confused about, can’t reliably define or measure, and have massive disagreements about even within EA. By default, that seems like a recipe for trouble. (2022)

That is, while Karnofsky now condemns it, he also expresses how he once believed in maximization. On the 80,000 hours podcast, reflecting on the scandal, Toby Orb expresses a similar view, discussing how he has changed his mind on maximization, advocating for EA to adopt the phrase ‘doing good better’ rather and avoiding the idea of ‘doing the most good’ (Ord et Wiblins, 2023). Indeed, Singer’s definition of EA from 2015 was just this, saying that “Effective altruism is based on a very simple idea: we should do the most good we can.” (Italics mine, 2015)

While EA has publicly come out against maximization, working to build the agreement that it is perilous and remove it from the EA ideology, maximization was also once a core idea within the EA community, which has led to the consequences philosophers have long warned against, significantly harming both the movement, and the world.

Crippling Individual Responsibility

Another undesirable idea EA has long believed in, again with utilitarian ties, is that individuals are responsible for all the good they can do. This idea can be seen in Singer’s drowning child thought experiment, concluding that “[l]iving a fully ethical life involves doing the most good we can” (Singer, 2015).

Particularly when combined with cause impartiality — a duty for life regardless of geography — this responsibility places enormous moral burden on individuals, asking them to be responsible for all of the suffering that might have prevented but did not, from that of an ant to the drowning of a child on the other side of the world. Any moment in which you are not doing the most you can to improve the state of the world, you fail to uphold your moral responsibility.

While most commonplace human activities, such as socializing, eating, or sleeping produce some amount of utility, they usually produce less utility than spending the same time working, making them immoral. Similarly, any utility you gain from buying a 5$ muffin is likely lesser than the utility someone else could gain if you donated that money to an effective charity. The effect on individuals is crippling: confronted with the responsibility for the suffering of the entire world, one must feel like Altas, unable to move from his strenuous position, for any deviation would result in suffering and pain. How can one do anything except for work?

This danger has long been flagged and discussed by philosophers. Bernard Williams called this implication of utilitarian negative responsibility. That is, because consequentialism does not take historic factors into account, it implies “that if I am ever responsible for anything, then I must be just as much responsible for things that I allow or fail to prevent, as I am for things that I myself, in the more everyday restricted sense, bring about.” (p. 83, 1973)

Within the EA community, this high moral burden can be seen in the high degree of burnout. In a EA forum post titled “The Garden of Ends”, Tyler Alterman tells his ultimately divergent story with Effective Altruism, expressing his guilt for when he wasn’t maximally productive, causing him tremendous stress.

What had finally tipped me into EA was an article. It proposed dead children as a unit of currency. “Here me out,” it said: It costs roughly $800 to save a child’s life through charity [at least this was the assumption at the time the article was written]. “If you spend eight hundred dollars on a laptop, that’s one African kid who died because you didn’t give it to charity. Distasteful but true.”

Well, fuck. I tried to escape the conclusion. But the logic was unstoppable. Hm. I was still young and poor; I didn’t have money, but I did have time. And so, soon after, I started to work 12-to-14-hour weekdays and weekends on EA causes. No amount of hours seemed like enough. How many hours did it take to raise $800? In my case — since I am decent at “networking” — probably a couple of hours, the length of one movie. So if I watched a movie instead of fundraising, a child was now dead. Did that mean watching a movie made me a murderer? I concluded: yeah. It did.

I extrapolated the implications of this. And so began a personal hell realm. As I crossed its borders, and continued to its interior, I went from being the happiest person I knew to eventually wanting to end my life. (2022)

Kerry Vaughan-Rowe, a founder of the EA Global conferences and and ex-head of outreach at CEA, tells a similar story, arguing that EA is dehumanizing:

EA [asks] people to value themselves based primarily on their “EA” contributions

Your value to the world becomes your ability to do those things, change those numbers.

The issue is that most people’s conception of a meaningful life is fundamentally multifaceted. But the EA ideology places no real boundaries on how much it demands, it naturally tries to consume everything else that provides meaning if it trades against being a better EA.

This creates a constant cycle of conflict between being an EA and everything else you want in life. (2022)

Alterman argues this is not an uncommon experience, saying: “As far as I can tell, my dark night experience represents a common one for especially devoted, or “hardcore” EAs — the type who end up in mission-critical roles.” (2022) A search on the EA forum returns many more posts discussing systemic burnout within the community.

This guilt to maximize one’s impact is compounded by the fact that under the premises of Singer’s thought experiment, individuals themselves hold no inherent value except for the utility they experience. Yet, the utility of any given individual is incomparable to that of the world, resulting in constant personal sacrifice for that of the world. Such an ideology does not prevent one from self-care and rest, but only finds it justifiable in the name doing more good. Crucial parts of one’s humanity — values, dreams and desires — that do not contribute to global well-being in the most effective way, are demanded to be given up and that energy repurposed towards improving the world.

Philosopher Nakul Krishna perhaps put it best in his article “Add your Own Egg” where he reflected on EA’s ideology, saying: “In this picture, it seems like the fact that I’m me has been declared, right at the outset, irrelevant.” (2016)

Towards a Better Ideology

In a way, EA has been the world’s most thorough experiment in the lived consequences of utilitarianism. While EA is not explicitly nor purely utilitarianism, no other group of people has taken utilitarian ideas so seriously in practice. In ways, the results have been predictable. None of the lived perils due to EA’s ideology should be new to philosophers, who have been discussing such dangers in the context of utilitarianism since the 1960s.

Given these flaws, should the EA movement entirely discard its ideology? And if it did, what, by definition of the community being held together by the ideology, would the movement be left with? Similarly, should someone who strives to ‘do good better’ still abide by the EA ideology? Do these flaws outweigh the good? What other options are there? And how might they equally be flawed? Alternatively, which elements of the ideology are sound and salvageable? How might the ideology be patched up and improved?

Regrettably, this section ends with many more questions than answers. To summarize: if we understand that implications from the EA ideology significantly impedes its goal of doing good better, what next? And further, how? While no small task, I leave this further discussion to the readers and the EA community. I hope the challenge will not impede those who try but only spur them on.

Yet, the first step is clear. The EA community — or at the very least, the ideological leaders of the community — must come to recognize the existence and nature of its ideology, and grapple with its flaws. It is only first through acceptance of what is, that it can be made better.

--

The Effective Altruism Community

What Happens to a Community Without Leadership

What is the EA Community?

Demographics

The EA community is relatively homogeneous. Respondents of the 2022 EA demographic survey were mostly male (66.2%), white (76.3%), young (median age of 29), left-leaning (76.8%), atheist (79.8%), and had high rates of attending prestigious universities (David_Moss et Willem Sleeger, 2023). A 2019 survey also found 69.6% of respondents identified with utilitarianism, with an additional 11.1% who identify with non-utilitarian branches of consequentialism (Neil_Dullaghan, 2019). Benjamin Todd estimated that there are “About 7,400 active members and 2,600 ‘committed’ members, growing 10–20% per year 2018–2020, and growing faster than that 2015–2017.” (Todd, 2021).

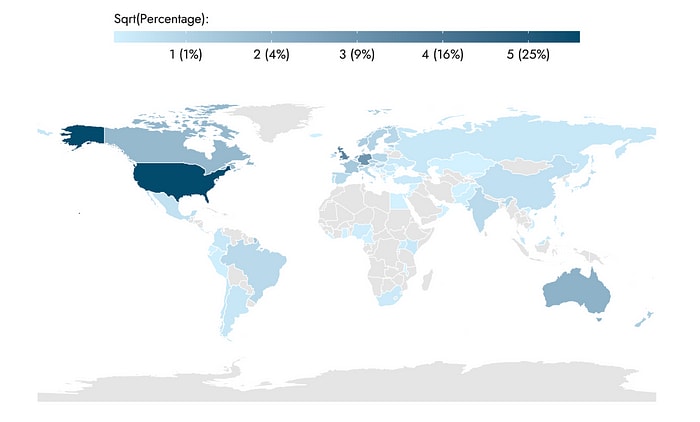

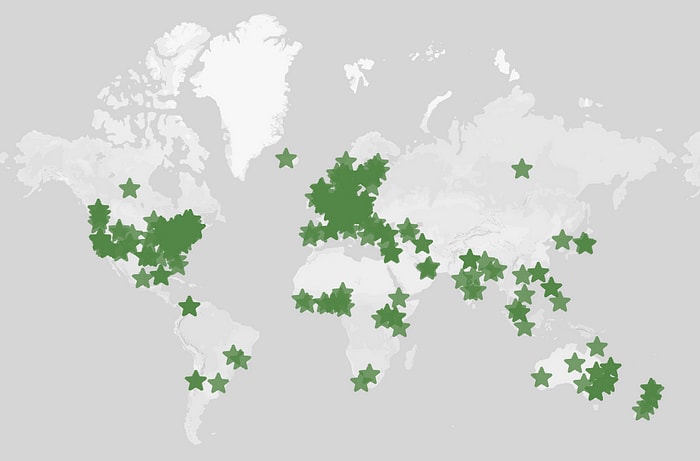

Most of the community is concentrated in a few hubs, such as SF Bay Area, Boston, NYC, DC, London, Oxford, which collectively make up about a quarter of the community.[2] The rest of the community is dispersed throughout the world, primarily through chapter groups, such as location-based groups like EA Oxford, EA Germany, or topic-based groups like EA for Christians (Figure 1). These groups often have independent forums, meeting groups, and are also able to run local conferences under the EAGx brand. For example, EA Germany is an independent legal entity, with its own governance structure and paid staff positions, although they receive the majority of their funding from CEA and Open Philanthropy (Effektiver Altruismus Deutschland, n.d.).

As of 2025, CEA lists 72 active local groups, and 50 active online groups, while the 2022 EA Survey had respondents from 76 countries (EA Forum, 2025; Jamie E & David_Moss, 2022). The result is that there are clear central nodes within the community, while much of the community also spread throughout the rest of the world, often with limited or differing channels of communication.

Organization

The EA community does not have formal membership criteria. While there are central EA organizations and platforms, they do not claim responsibility over the EA community or brand. As a result, the EA identity and brand do not have any formal barriers to entry: anyone can self-identify as part of the community, or start a project that has ‘Effective Altruism’ in the name (MacAskill, 2023).

The EA community also practices notable social norms, including an emphasis on rationality, the encouragement of criticism, a willingness to be weird, and the practice of polyamory. These norms are far from universal across the community and are not representative of any individual.

Importantly, the EA community is a social one. While the community has many professional elements, it is also a social community, with common practices like living in group houses and EA gatherings. While the social element creates strong ties within the community, it also creates pressure to adhere to social norms, as well as difficulty in disentangling professional and social lives.

The EA Forum, an online forum, is the main medium of communication and discussion for the community, and serves as a town hall. Posts range from discussions of developments in EA cause areas, about career opportunities, and about the EA community itself. While there is a karma system which weighs the opinions of higher rated users more heavily in determining the algorithmic salience of posts, the platform has minimal barriers to entry and allows anyone to post, comment, and engage.

The Distribution of Power

Another salient feature to understand the EA community is the distribution of power within the community, revealing how decisions are made. Looking at the distribution of power also highlights who the leaders of EA are.

Yet, it is not immediately clear where power lies and what it looks like. Here, we look at three forms of power, following Luke Steven’s three faces of power framework. The three interconnected sources of power are: decision-making power — control over resources and formal decisions, agenda-setting power — influence over which issues and projects gain attention, and ideological power — the ability to shape the movement’s ideology.

Decision-Making Power

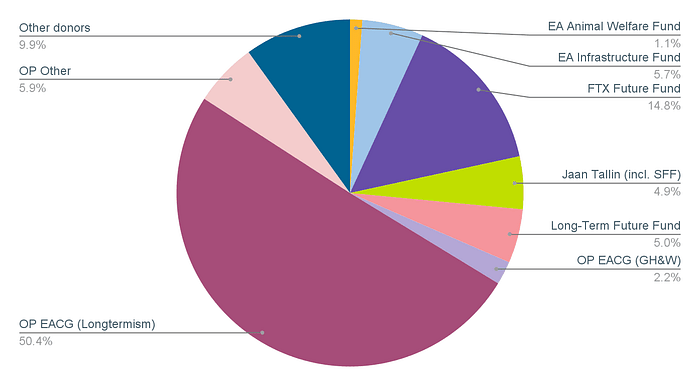

Decision-making power in EA is highly concentrated due to the control of funding. About 70% of funding for EA movement building originates from a single source, Open Philanthropy, giving a small group of people great influence over the direction of the movement through the power to allocate funding (Figure 1).[3] Specifically, Open Philanthropy is funded almost exclusively by Good Ventures, a foundation which manages the personal wealth of Cari Tuna and Dustin Moskovitz. However, Tuna and Moskovitz rely heavily on the research and recommendations of Open Philanthropy, meaning most of the decision-making power within the EA movement originates from Open Philanthropy.

Other funders do exist, but none rival the scale or central role of Open Philanthropy. Notably, EA once had significant funding committed from FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried prior to his incarceration, and has also received funding from Skype co-founder Jaan Tallinn. However, in totality, these other sources of funding have been marginal in comparison to the funding from Open Philanthropy.[4]

This concentration of power is a common cause of frustration within the community, particularly when the interests of Open Philanthropy differ from that of the EA movement. For example, when Good Ventures updated their grantmaking focus areas in 2024, there was much turmoil on the EA Forum as the community grappled with the consequences for the movement. Within the comment section of a discussion, Moskovitz said, replying to frustrated member of the community:

… my apparent power comes from not having alternate funding sources, not from structural control. Consequently, you and others lay blame on me even for the things we don’t do…. I did not want to create a [Open Philanthropy] hegemony any more than you wanted one to exist (Moskovitz, 2024).[5]

Agenda-Setting power

Also known as non-decision-making power, agenda-setting power is more subtle and dictates priorities and discourse. One source of this power is again the control of funding, influencing what topics are on and off the table. Notably, the majority of Open Philanthropy funding flows out of their ‘Effective Altruism Community Growth (Longtermism)’ portfolio (50.4% according to Agrawalla’s estimates), which is focused on catastrophic risks to humanity, such as AI safety and biosecurity, but does not include causes like global poverty and animal welfare.[6]

Agenda-setting power also comes from doing coordination work, such as having control over external branding and communications, or mediums of organization. Within EA, the three main areas of coordination are the EA Forum, the EA Global conferences, and the Effective Altruism website, and are all operated by the Center for Effective Altruism (CEA). This gives CEA power to dictate the branding, values, and ideas associated with the movement. For example, the design of the EA Forum, inadvertently or not, prioritizes certain ideas, such as through search and content algorithms, definitions of EA’s core topics, or content in the EA handbook.[7] This is also relevant in the design of the EA Global conferences, such as in the choice of keynote speakers, and session topics, admissions.[8]

Agenda-setting power is thus also concentrated within the EA community, held by the leaders of Open Philanthropy and the Center for Effective Altruism.

Ideological Power

Sometimes also called invisible power, a third form of power is ideological. This type of power is to shape EA’s ideology and the ideas that the community believes, and is derived from the ability to persuade others and shape opinions. In contrast to decision-making and agenda-setting power, ideological power in the EA movement is more diffuse.

Within the community, this power lies primarily with prominent figures and thought leaders for the EA movement, such as William MacAskill, Toby Orb, and Holden Karnosky. Importantly, this power also lies with individuals who might not necessarily consider themselves part of the community, including Peter Singer, Elizer Yudkowski, and Scott Alexander, through their readership and influence within the EA community.[9]

Ideological power is also accessible to all members of the community through the ability to spread ideas and influence social norms, largely through the EA Forum. Some examples include Helen Toner’s post about the EA ideology, Julia Wise’s post about power dynamics, or Habryka’s post on immoral behavior in the community[10]. Ideological power is also the type of power I am leveraging with this piece.

The Governance of Power

Overall, power is highly concentrated within the EA movement, primarily with Open Philanthropy and the Center for Effective Altruism. This may not in itself be problematic. After all, effective governance and leadership requires the exercise of power, such as an elected officials’ power within a government, or a CEO’s power within a company.

However, effective governance also requires mechanisms that ensure power is exercised efficiently and justly. This is the role of the legal system within governance, or the role of a board within the company. While EA does have concentrated power, it lacks structures to ensure that power is used for the good of the movement.

Insufficient Governance

Importantly, certain organizations within EA do have some governance mechanisms. Most notably, EA organizations, including Open Philanthropy and Effective Ventures, have governance boards, whose role is to ensure the health and strategic direction of a company, creating accountability for the CEO. However, the role of boards has historically been neglected within EA, often seen as a rubber stamp rather than a necessary balance of power.

While this can not be generalized to all EA organizations — indeed, some have recently started the EA Good Governance Project, whose mission is to help EA organizations create strong boards — there are many historic examples of governance being neglected within core organizations and the community. In a post on the EA Forum arguing EA has weak governance norms, James Fodor highlights six examples where “inadequate organisational structures and procedures” led to issues within EA or EA-adjacent organizations. These include:

- Weak governance structures and financial oversight at the Singularity Institute, leading to the theft of over $100,000 in 2009.

- Inadequate record keeping, rapid executive turnover, and insufficient board oversight at the Centre for Effective Altruism over the period 2016–2019.

- Inadequate financial record keeping at 80,000 Hours during 2018.

- Insufficient oversight, unhealthy power dynamics, and other harmful practices reported at MIRI/CFAR during 2015–2017.

- Similar problems reported at the EA-adjacent organisation Leverage Research during 2017–2019.

- ‘Loose norms around board of directors and conflicts of interests between funding orgs and grantees’ at FTX and the Future Fund from 2021–2022. (Hyperlinks his; Fodor, 2022)

Another example comes from Givewell, an early and well-respected EA organization. In 2019, three of its then eight board members decided to resign due to Givewell leadership’s disregard of the role in the board. Rob Reich wrote in his resignation letter:

Board meetings are too frequently nothing more than the performance of meeting legal obligations. For an organization as large and as important as GiveWell, the oversight of GiveWell operations should be much greater, and welcomed by GiveWell leadership as an opportunity for diversifying input on GiveWell strategy. (Reich, 2019)

Brigid Slipka echoed similar sentiments in hers:

…I am unsettled by the decision to reduce the Board down to a hand-picked group of five, two of whom are the co-founders and another of whom is the primary funder… This feels regressive. It represents a tightening of control at a moment when the focus should be on increased accountability to the public GiveWell serves. (Slipka, 2019)

While governance does technically exist within EA organizations, there is evidence that they often fail to serve their purpose and are unable to provide proper accountability for the actions of those they are intended to serve.

EA’s Informal Structure

EA’s poor governance is compounded by its lack of official leaders or titles. MacAskill, a founder of the movement, has said: “[t]here’s no one, and no organisation, who conceives of themselves as taking ownership of EA, or as being responsible for EA as a whole.” (MacAskill, 2023)[11] Similarly, despite the name ‘Center for Effective Altruism’, CEA’s website reads: “We do not think of ourselves as having or wanting control over the EA community.” (Center for Effective Altruism, n.d.) Neither does their mission make any reference to Effective Altruism.[12]

This is not to say neither MacAskill and CEA are not leaders of EA. As seen by their status and past actions, they both control significant power within the movement, and have significant influence and say over the direction of the movement. What they do not have are formal obligations or responsibilities to the movement or the community. That is, their leadership is informal.[13]

Another consequence of EA’s informal structure is the lack of formal governance over its brand, reputation, and ideology. While the Centre for Effective Altruism (CEA) holds considerable influence within the community, it explicitly avoids responsibility for defining or safeguarding EA’s identity. This governance vacuum creates ambiguity regarding what precisely constitutes EA and how accountability should function within the movement. For example, as discussed in part two, such ambiguity compromises the community’s capacity to maintain the integrity, coherence, and ethical rigor of its core principles.

Most importantly, those who make decisions for the EA movement, do not owe any formal responsibility to the movement itself. Should an individual or organization take actions that are irresponsible or harmful for the EA movement, there are no established mechanisms for the movement at large to check those actions.

The Tyranny of Informal Structure

While the EA movement lacks formal structure, this does not to say that it is structureless. Rather it is informally structured. It is not that the EA community lacks rules, but rather that the rules within the community are not publicly stated. Minimizing formal structures can be appealing. Yet, it can also have unintended effects. Sociologist Jo Freeman writes:

[In informally structured groups, t]he rules of how decisions are made are known only to a few and awareness of power is curtailed by those who know the rules, as long as the structure of the group is informal. Those who do not know the rules and are not chosen for initiation must remain in confusion, or suffer from paranoid delusions that something is happening of which they are not quite aware. (Freeman, 2013)

Informality does not change the balance of power, but only obscures it. In fact, this can create the false pretense that there are no elites, which only further entrenches the power of those elites. Freeman writes:

All groups create informal structures as a result of the interaction patterns among the members. Such informal structures can do very useful things. But only unstructured groups are totally governed by them. When informal elites are combined with a myth of ‘structurelessness’, there can be no attempt to put limits on the use of power. It becomes capricious.

This has two potentially negative consequences of which we should be aware. The first is that the informal structure of decision-making will be like a sorority: one in which people listen to others because they like them, not because they say significant things….

The second is that informal structures have no obligation to be responsible to the group at large. Their power was not given to them; it cannot be taken away. Their influence is not based on what they do for the group; therefore they cannot be directly influenced by the group. This does not necessarily make informal structures irresponsible. Those who are concerned with maintaining their influence will usually try to be responsible. The group simply cannot compel such responsibility; it is dependent on the interests of the elite. (Freeman, 2013)

That is, in informal groups like EA, rules of engagement are often unstated and power is obscured, harming the community’s epistemic culture and creating a lack of accountability. Both of these negative consequences can be seen in EA.

EA’s Epistemic Culture

In part due to its roots in the Rationality community, one strong focus within the EA community has been on the community’s epistemics — the forming of correct beliefs — developing norms with the goal of maintaining a high standard of knowledge and ways to seek new knowledge. For example, it is common for posts on the EA forum to start with a section titled ‘Epistemic Status’ — where the author states their level of confidence in the piece — for references to a ‘Scout Mindset’ — the motivation to see things as they are, not as you wish they were — or the practice of decoupling — to not let prior evidence impact one’s evaluation of new evidence.

In fact, these epistemic norms are stated within the EA Forum Guide, which also prefaces “the more sensitive a topic is, the more these norms matter and will be enforced” (Lizka, 2022). In this sense, these epistemic norms are formal rules, being publicly stated and enforced, presumably through moderation. Practically, enforcement also happens socially, such as in downvoting or commenting on posts which don’t follow norms.

While EA’s epistemic culture does have formal structure for discussion norms, it lacks formal structure for the quality of content, to ensure that truth is upheld. Some examples of formal structures for the quality of content include the peer review process in academia or editors and fact checkers in journalism. That is, the quality of the EA’s epistemic culture is dependent on informal structures like social pressure rather than objective standards.

The medium of the EA Forum does provide some tools for informally maintaining epistemic standards through its sophisticated methods of allowing users to rate posts and their content, giving more weight to the opinions of higher-rated users, leveraging market forces and expert voices to select for quality. Yet, it is unclear whether this system actually benefits EA’s epistemic culture, as it has also been criticized for fostering groupthink through institutionalizing an unequal weight to certain individuals’ voices, specifically those who are popular, although not necessarily correct

Discourse with adjacent fields has been rare, often approached maliciously by both sides, characterized by ad hominem attacks instead of engaging charitably with the arguments presented. For example, in discussing Stanford philosopher Wenar Lief’s sharp-tongued critique of EA, Geoffrey Miller wrote, receiving a flurry of up- and down-votes:

Some people, including many prominent academics, are bad actors, vicious ideologues, and/or Machiavellian activists who do not share our world-view, and never will. Most critics of EA will never be persuaded that EA is good and righteous. When we argue with such critics, we must remember that we are trying to attract and influence onlookers, not trying to change the critics’ minds (which are typically unchangeable). (Miller, 2024)

Yarrow replied to equal controversy: “This seems to me to be a self-serving, Manichean, and psychologically implausible account of why people write criticisms of EA.” (2024)[14]

Some epistemic checks and balances have come from EA’s engagements with journalism. Vox’s Future Perfect, whose mission is to “cover[] the most critical issues of the day through the lens of effective altruism”, also funded in part by EA organizations, has run many pieces covering developments in and critiquing the EA movement.

There are instances where journalistic efforts have helped address important issues within the community, such as a Time article about sexual harassment and abuse within the EA community which led to a formal investigation, a resignation, and changes to CEA’s community health team.[15]

Information Cascades

A common epistemic practice within the EA community is deference, the idea of relying on the judgement of more qualified individuals, with members often citing and referring to each other as sources of evidence and authority. While learning from each other is not in itself a problem, in absence of robust standards for knowledge, deference can lead to the uptake of false premises and group think, known as an information cascade (Jalili et Perc, 2017).

For example, philosopher David Thorstad, in his blog Reflective Altruism, documents a case where Toby Orb painted an incomplete picture evidence about the tractability and therefore benefits of working on biorisk, missing significant political complexities, and ultimately reaching conclusions at odds with the scientific literature and reality. These claims went on to be repeated by 80,000 Hours, and Giving What We Can, two core EA organizations, and from there into the rest of the community, resulting in a belief at odds with the expert consensus on the subject. Thorstad goes on to describe a similar second instance where Toby Ord, Piers Millett, and Andrew Snyder-Beattie perpetuated an inflated claim about the risks from bioweapons, again at odds with the expert consensus (Thorstad, 2023).

Discussing this topic, the account ConcernedEAs, a group of ten anonymous and committed Effective Altruists, summarized:

EA mistakes value-alignment and seniority for expertise and neglects the value of impartial peer-review. Many EA positions perceived as “solid” are derived from informal shallow-dive blogposts by prominent EAs with little to no relevant training, and clash with consensus positions in the relevant scientific communities. Expertise is appealed to unevenly to justify pre-decided positions.

…Under the wrong conditions, newcomers can rapidly update in line with the EA “canon”, then speak with significant confidence about fields containing much more internal disagreement and complexity than they are aware of, or even where orthodox EA positions are misaligned with consensus positions within the relevant expert communities.

More specifically, EA shows a pattern of prioritising non-peer-reviewed publications — often shallow-dive blogposts — by prominent EAs with little to no relevant expertise. These are then accepted into the “canon” of highly-cited works to populate bibliographies and fellowship curricula, while we view the topic as somewhat “dealt with”’; “someone is handling it’’. It should also be noted that the authors of these works often do not regard them as publications that should be accepted as “canon”, but they are frequently accepted as such regardless. (ConcernedEAs, 2023)

Notably, EA’s overreliance on deference was initially established as a mechanism to improve its epistemic culture and mitigate biases. This is exemplified in Gregory Lewis’ widely-cited piece ‘In defence of epistemic modesty’ where he argued that deference “is a superior epistemic strategy, and ought to be more widely used — particularly in the EA/rationalist communities” (Lewis, 2017). However, experience shows us that this strategy has backfired, instead perpetuating group think and confirmation bias, and poisoning EA’s epistemic culture.

Equally, EA is far from unaware of the dangers of information cascades, being a commonly cited concern. Yet, it is also clear that simple awareness of a bias is not enough to prevent its perpetuation. That is, the pressure and norm to defer often overwhelms any individual’s ability to critically assess information and stop the propagation of faulty information or ideas.

One key is the fact that EA is a social community, introducing pressure to conform to the opinions of one’s friends and the crowd. Speaking out against popular consensus can be threatening to one’s social life as well as professional prospects, evidenced by the number of accounts created anonymously explicitly for the purpose of speaking out against popular opinion without harming one’s professional or social prospects. Others have been more explicit, such as Izo talking about social validation being a driving force in the community, Ben Millwood talking about the illusion of consensus, or Ben Kuhn and Denise_Melchin discussing social pressure to defer to others.

Overall, the lack of formal structure, placing responsibility on individuals to assess the validity of information, combined with social pressures to conform to the norm, creates an epistemic environment susceptible to the propagation of both fallacious beliefs and morally flawed attitudes. The perpetuation of problematic ideas in the EA ideology is another example of the danger of information cascades.

The Illusion of Criticism

Another result of a lack of epistemic structure is that in spite of the stated norm that all criticism is welcome, there have been many instances where certain criticisms have been heavily discouraged through the use of threats and power. Such instances are harmful in their own right, and particularly so when done so under the pretense of epistemic health and openness.

For example, Carla Zoe Cremer and Luke Kemp detailed how they faced persistent and personal backlash for a paper they published criticizing longtermism, being threatened with future professional and funding prospects, straining their relationships in the process (2021). They write:

The EA community prides itself on being able to invite and process criticism. However, warm welcome of criticism was certainly not our experience in writing this paper.

Many EAs we showed this paper to exemplified the ideal. They assessed the paper’s merits on the basis of its arguments rather than group membership, engaged in dialogue, disagreed respectfully, and improved our arguments with care and attention. We thank them for their support and meeting the challenge of reasoning in the midst of emotional discomfort. By others we were accused of lacking academic rigour and harbouring bad intentions. (Cremer et Kemp, 2021)

Later reflecting on by her experiences, in a Vox Future article advocating for better governance in EA, Zoe Cremer wrote:

I was entirely unsuccessful in inspiring EAs to implement any of my suggestions. MacAskill told me that there was quite a diversity of opinion among leadership. EAs patted themselves on the back for running an essay competition on critiques against EA, left 253 comments on my and Luke Kemp’s paper, and kept everything that actually could have made a difference just as it was. (Cremer, 2023)

Similar sentiments about the false illusion of open criticism can be found throughout the EA Forum. While EA’s efforts to welcome criticism should be commended and practiced more widely, what can not be tolerated is the false narrative that EA does this successfully. It is natural and unavoidable that people do not react rationally to comments that threaten their self-esteem. Creating the illusion that this does not happen only further harms a community’s epistemics.

Cause Prioritization

Another epistemic failure of the EA community is the way longtermism, a philosophical view that prioritizes the long-term future of humanity, has been backhandedly favored over other causes in EA community building, skewing decision-making. The majority of funds Open Philanthropy distributes to the EA movement are categorized under their ‘Global Catastrophic Risks’ portfolio, which, by definition, includes causes like AI safety and biorisk, but not those like animal welfare or global health. Open Philanthropy has more recently begun funding EA movement building through their Global Health and Wellbeing portfolio, but this accounts for only 2.2% of the total EA movement building funding, compared to 50.4% from their Global Catastrophic Risks portfolio (Agrawalla, 2023). In fact, an estimated 70.3% of overall EA movement building funding has come from a source with an explicitly longtermist agenda, heavily influencing the direction of the movement. For example, in an EA Forum post, Zachary Robinson, the current CEO of CEA, acknowledges on this power dynamic, saying:

“While I don’t think it’s necessary for us to share the exact same priorities as our funders, I do feel there are some… practical constraints insofar as we need to demonstrate progress on the metrics our funders care about if we want to be able to successfully secure more funding in the future.” (Robinson, 2024)

Perhaps due to these funding constraints, CEA also has a history of favoring longtermist cause areas. This is openly admitted on their ‘Mistakes’ page, where they describe five instances where their initiatives were biased towards certain cause areas on their mistakes page, such as in failing to adequately represent other EA causes in the EA handbook or the Effective Altruism website, misrepresenting EA to the world. Starting in 2022, CEA also opened a page openly acknowledging their responsibility over the EA movement, providing some insight into their approach to moderation and content curation, saying:

The Centre for Effective Altruism is often in the position of representing effective altruism…. We think that we have a duty to be thoughtful about how we approach these materials. (Center for Effective Altruism, n.d.)

A Lack of Accountability

In the absence of formal mechanisms, there has been minimal accountability for any individual’s actions within EA. Yet, while the community has often expressed disappointment with their leaders, the leaders often feel unfairly burdened with expectations and responsibilities they did not formally agree to. Writing about EA’s lack of formal leaders in an EA Forum post, MacAskill reflects:

This is the part of the post I feel most nervous about writing, because I’m worried that others will interpret this as me (and other “EA leaders”) disavowing responsibility; I’m already anxiously visualising criticism on this basis. (MacAskill, 2024)

In a footnote he goes on to speculate:

A simple explanation for the discrepancy [between how leaders and the community see decision-making in EA working] is just: [leaders of] EA haven’t clearly explained, before, how decision-making in EA works. In the past (e.g. prior to 2020), EA was small enough that everyone could pick this sort of thing up just through organic in-person interaction. But then EA grew a lot over 2020–2021, and the COVID-19 pandemic meant that there was a lot less in-person interaction to help information flow. So the people arriving during this time, and during 2022, are having to guess at how things operate; in doing so, it’s natural to think of EA as being more akin to a company than it is, or at least for there to be more overarching strategic planning than there is. (MacAskill, 2024)

The result is a lack of action, as the community expects those in power to act, while those in power do not feel they are responsible to act. This hinders the ability of the movement to prevent and correct wrongdoings, as well as to learn from them.

The Center for Effective Altruism

With no direct accountability to the community or for their actions, CEA has had many instances of failing to hold up their commitments, lacking transparency to the community its name is tied to, and lacking meaningful evidence of learning from past mistakes. One example comes from EA Funds, which was launched by CEA to help “EAs give more effectively at lower time cost” (MacAskill, 2017). Yet, a year later, detailing how certain sub-funds were being neglected and consistently under delivered, EA Forum user Evan_Gaensbauer wrote:

The juxtaposition of the stagnancy of the Long-Term and EA Community Funds, and the CEA’s stated goals, create a false impression in and around the movement the CEA can be trusted to effectively identify promising projects from within the community within these focus areas. (Gaensbauer, 2018)

User AnonymousEAForumAccount expanded four years later, detailing a continued history of cases where the fund failed to provide regular updates, grant disbursement was slow, failed to provide accurate data about fund financials, and regularly portrayed the platform in an overly positive light, setting false expectations and mischaracterizing outcomes (2022).

In the same post, AnonymousEAForumAccount went on to discuss detail seven more cases where CEA took on community-building projects that were characterized by similar mistakes and flaws, including under-delivering on stated commitments, missing deadlines, understating and omitting important mistakes made, and lacking meaningful evaluation of results (2022).

These persistent and unowned mistakes, symptomatic of the planning fallacy, not only harm the community through failure to deliver on commitments. They also create a sense of distrust, harming future ability to coordinate and operate effectively as a movement.

FTX

The FTX scandal is particularly illuminating. In the aftermath of the FTX Within EA, the community came out to express mass outrage and condemnation at EA’s relationship to Bankman-Fried. For example, it was reported that MacAskill and multiple other EA leaders had long been aware of concerns around Bankman-Fried. MacAskill had been personally cautioned by at least three different people (Alter, 2023). EA was also heavily integrated into the FTX ecosystem. FTX’s director of engineering Nishad Singh has said that Alemeda Research, a cryptocurrency-oriented hedge fund closely tied to FTX which Bankman-Fried also founded “couldn’t have taken off without EA,” because “all the employees, all the funding — everything was EA to start with.”(Fisher, 2022) For example, Tara Mac Aulay co-founded Alameda Research with Bankman-Fried while simultaneously serving as the CEA of CEA.

Addressing the scandal, MacAskill wrote: “I was probably wrong. I will be reflecting on this in the days and months to come, and thinking through what should change.” (2022) Yet, it wasn’t clear that anything would change. In the immediate aftermath, no individuals or organizations came forward to take responsibility, nor were any substantial investigations done into EA’s exact involvement with FTX. In the aftermath of the scandal, Gideon Futerman expressed disappointment at EA leadership, citing “unaccountable, centralised and non-transparent” power structures:

The assumption I had is we defer a lot of power, both intellectual, social and financial, to a small group of broadly unaccountable, non-transparent people on the assumption they are uniquely good at making decisions, noticing risks to the EA enterprise and combatting [sic] them, and that this unique competence is what justifies the power structures we have in EA. A series of failure [sic] by the community this year, including the Carrick Flynn campaign and now the FTX scandal has shattered my confidence in this group. (2022)

Rob Bensiger similarly expressed his frustration on X:

17 months post-FTX, and EA still hasn’t done any kind of fact-finding investigation or postmortem on what happened with [Sam Bankman-Fried], what mistakes were made, and how we could do better next time. There was a narrow investigation into legal risk to Effective Ventures last year, and nothing else since. (2024)

Discussing her resignation from the board of Effective Ventures, Rebecca Kagan stated: “I want to make it clear that I resigned last year due to significant disagreements with the board of EV and EA leadership, particularly concerning their actions leading up to and after the FTX crisis.” (2024)

Strikingly, Bankman-Fried may not the first crypto billionaire involved in fraud EA has been affiliated with. Between 2018 and 2020, Ben Delo, similarly a founder of a cryptocurrency exchange, BitMEX, donated to many EA organizations, and was used by EA leaders as an example of an important donor. Strikingly, it is reported that Delo also had a close relationship with William MacAskill, who discussed Delo by name on multiple occasions as an important new donor at EA conferences (Alter, 2023; Kerry Vaughan-Rowe, 2022). This relationship ended in 2020, when Delo was indicted by the CFTC and the US Department of Justice for failing to implement an adequate anti-money laundering program. The incident has since been kept quiet within the EA community, and it is unclear whether any precautions were taken in the aftermath.[16]

The Need for Governance