Here are my own current thoughts on those questions. These thoughts are of course tentative, and my main aim here is to learn more on this matter (otherwise I would’ve made a regular post rather than a question post):

On Q1: It seems like it’s rare for research orgs to make (publicly accessible) ToC diagrams? As I said, I only know of two examples of research orgs that have made such diagrams. But I haven’t done a systematic or extensive search.

If it’s indeed uncommon for research orgs to make ToC diagrams, that might be due to the “potential downsides” I list below.

On Q2: I have basically no evidence regarding whether many orgs make non-public ToC diagrams. I’ve never seen an example of that, but that’d likely be the case even if there are many such non-public diagrams, since I’ve only worked at one research org thus far (Convergence), and their ToC diagram was public anyway.

On Q3: My independent impression - i.e., what I’d believe if I wasn’t updating my beliefs based on what others seem to believe - is that, indeed, more research orgs should make ToC diagrams. But if so few research orgs do that, and most research orgs are run by smart people, maybe I should interpret that as evidence that there’s some good reason not to do this which I’m missing?

But I’m not sure how strong that update should be, because it might be more a matter of norms, inertia, and/or not having thought of doing this.

Some potential benefits of making ToC diagrams (even if they aren’t publicly accessible) that came to my mind are that doing so could help the org:

- Make decisions about which research questions/directions to pursue

- E.g., maybe you’d realise that a line of research that seems fascinating to your researchers actually doesn’t have any clear path to influencing your intended outcomes. This would likely push in favour of deprioritising that line of research. (But this consideration could be outweighed. See also Can we intentionally improve the world? Planners vs. Hayekians)

- Make decisions about which audiences to target

- E.g., you might realise that, in order to achieve your ultimate intended outcomes, you mainly need to influence decisions by [policymakers / AI researchers / EAs interested in global health / company leaders / whatever]. You can then have that in mind as you choose research questions, writing styles, types of output (e.g., EA Forum posts vs academic articles), etc.

- Make decisions about what non-research activities to do, how to do them, and how much time to allocate to them

- E.g., you might realise that most of the outcomes you want to bring about require specific people to read your work, such that it’s worth dedicating a decent amount of time to building relationships with those people, attending relevant conferences, etc., rather than just doing research and assuming it’ll have an impact somehow.

- Work out how they can assess their progress and their impact

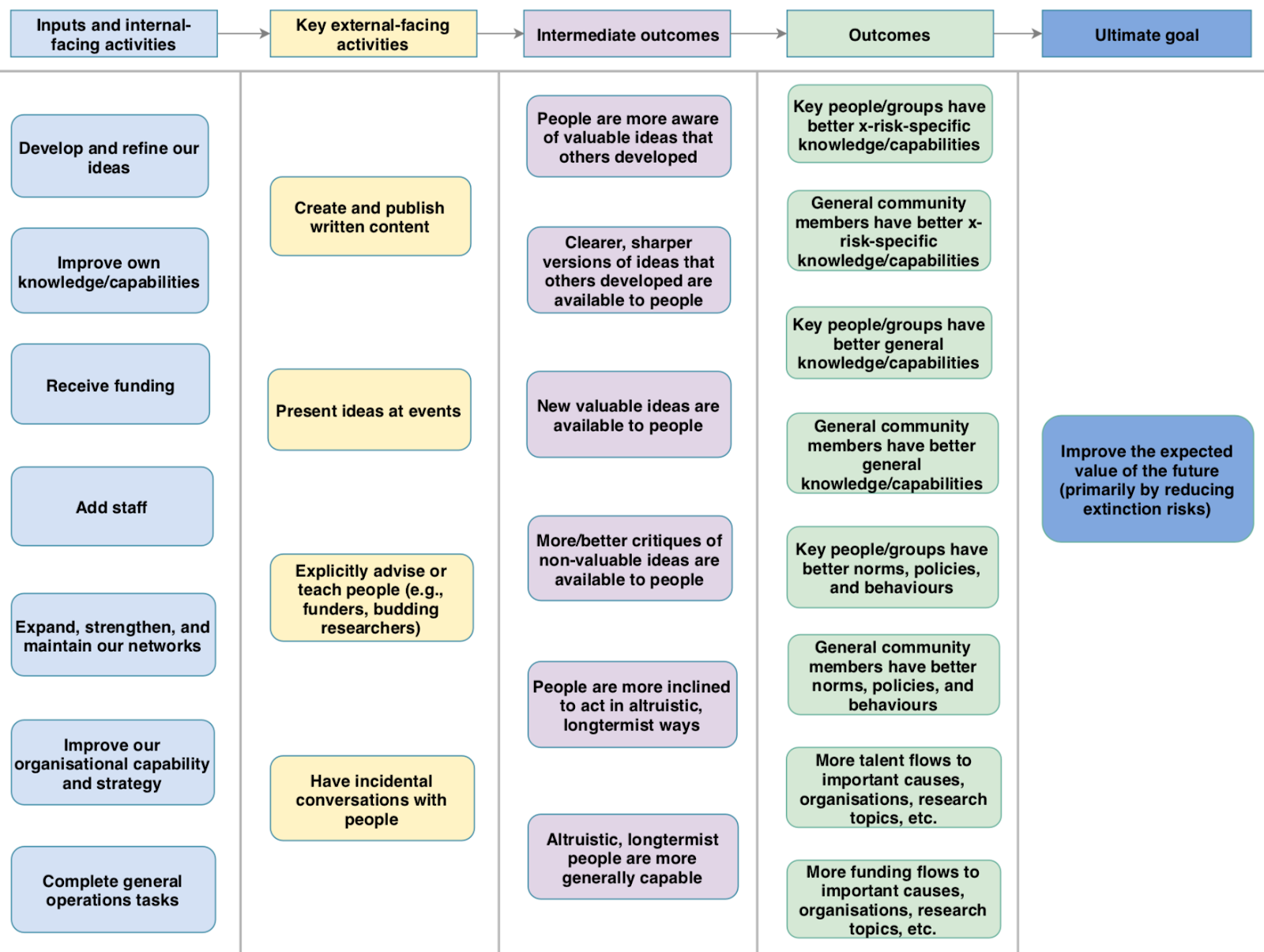

- E.g., my personal opinion is that, once Convergence had made a ToC diagram, this helped us come up with metrics for assessing our progress and impact. It’s practically impossible to “directly” assess whether one has improved the expected value of the future (which was our ultimate aim), but easier to assess how well we’re achieving outcomes on the causal path from our actions to that outcome.

- Note I said “easier” rather than “easy”, and that I’m comparing this to something that’s “practically impossible” - I definitely still find assessing the impact of longtermist research very difficult!

(Note that each of those benefits could likely be captured to at least some extent by an org just describing their theory of change fairly explicitly, without actually making a diagram about it. The same point applies to the remainder of this “answer”.)

And some potential downsides of making ToC diagrams that came to my mind are that doing so could:

- Take up a lot of time

- Not actually provide much clarity anyway

- Lead to focusing too much on a particular set of paths to impact that one explicitly maps out, at the expense of doing things that seem worthwhile based on intuitions and heuristics

- See again Can we intentionally improve the world? Planners vs. Hayekians, and perhaps also Goodhart’s law.

- Of course, it’s hard to say when it’d be better to operate based on intuitions and heuristics rather than a ToC

- It also seems possible that the ideal would be to make a ToC, and sometimes/often refer to it, but not always refer to it or always require that a project “fits” within that ToC.

On Q4: I’d guess that, if a research org has a ToC diagram, it’d typically make sense to make it publicly accessible. This could mean actively sharing it (e.g., in a post like this one or this one), making it prominently visible on the org’s website, or burying it in some obscure corner of the org’s website.

Some potential benefits of making ToC diagrams publicly accessible (rather than just making them in the first place) that came to my mind are that doing so could:

- Help potential donors, potential employees, etc. understand why you’re doing what you’re doing, and thus make informed decisions about whether to donate to you, work for you, etc.

- E.g., perhaps what you’re doing seems inefficient or unlikely to connect to important real-world outcomes unless people understand your ToC

- Or perhaps what you’re doing is misguided, and it’d be good for the world for people to have more evidence of that if that’s true, so that they can then support something better instead

- Help other orgs learn from and adopt clever aspects of your strategy and thinking

- Help stakeholders coordinate with you or support you

- I’m less sure what I could mean by this point

- One vague and speculative example: If many orgs’ ToC diagrams suggest that a particular type of conference would be useful in order for those orgs to make their research impactful, and those ToC diagrams are publicly accessible, this could lead to someone setting up such a conference.

(It might be possible to capture some of these benefits by just sharing ToC diagrams with specific people, such as potential donors or employees, rather than making those diagrams totally publicly accessible.)

And some potential downsides of making ToC diagrams publicly accessible that came to my mind are that doing that could:

- Lead to misperceptions about an org’s strategy

- E.g., it could lead to stakeholders focusing too much on the set of pathways to impact highlighted in the ToC diagram (rather than other, vaguer reasons to believe impact might occur), or perceiving the org’s thinking as quite simplistic

- Allow other actors to harm your org or harm things you value, as a result of them learning from your strategy and thinking

- E.g., another research org might improve itself by adopting some of your ideas, and then get some funding you’d have otherwise gotten

- But maybe there’s often little harm in that, as that other org could then do useful things as well

- More speculatively, if there’s some actor that actively wants to prevent you accomplishing your mission, perhaps seeing your ToC would make that easier for them

But again, these are just my current, tentative thoughts, and I’m primarily interested in hearing what others have to say!

My thanks to Courtney Henry and David Kristoffersson for discussions that informed this answer.