As part of conducting research into my Tactics in Practice series (reports designed to understand the impact and potential improvements to common interventions to improve animal welfare), I am often a bit let down by what the research says. After reviewing the evidence behind vegan and meat-reduction challenges and pledges, I have to say I am more optimistic about this tactic than I was before investigating it. I believe they have the potential to shift collective diet change more than most people think.

Read the Full ResourceTo my knowledge, this is the first meta-analytic resource on the topic, combining both public studies, internal data, and gray literature, so I think the results are super important for anyone thinking about this intervention.

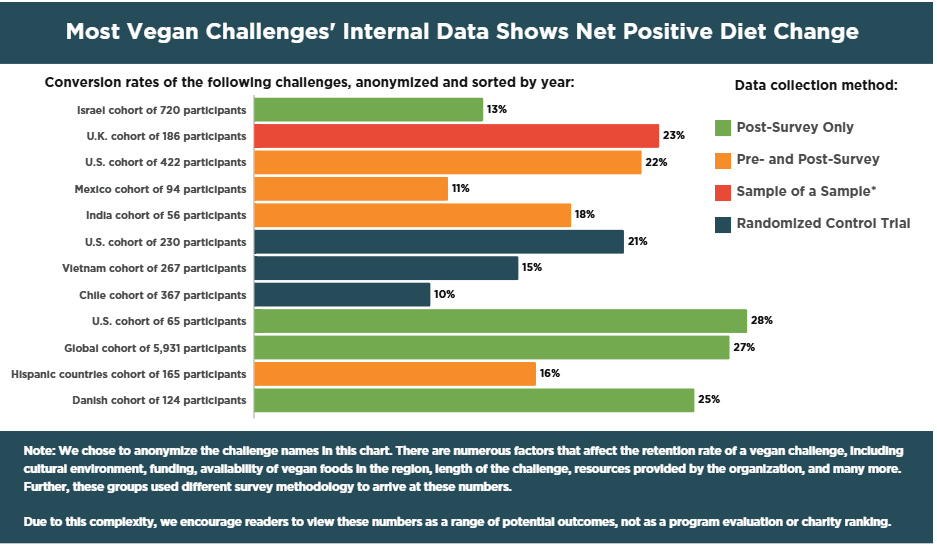

- In the data I examined (which includes some non-public data), Vegan challenges have a retention rate between 10 and 28%. (Keep in mind, this is a rough range! The data I looked at used varying methodologies, regions, challenges, and definitions of vegan retention, but it’s still a good glimpse of what a well-executed vegan challenge can accomplish).

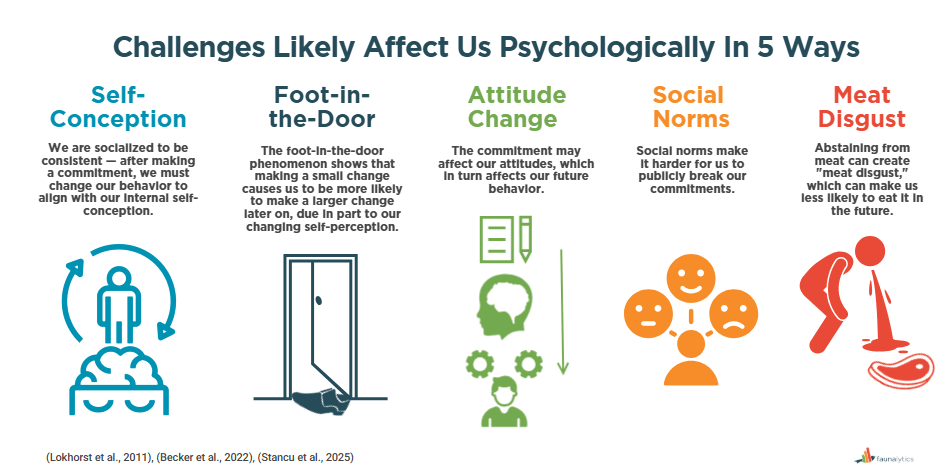

- Challenges work via multiple, often interconnected psychological mechanisms. See the attached graphic for details.

- Mainstream veggie challenges like Veganuary and Meatless Mondays likely make people eat less animal products after the challenge period (on other days of the week for MM and in other months for Veganuary). To me, this is key. It shows long-lasting effects of the challenges even if they aren't a "perfect vegan" afterwards, alligning well with reductionist messaging.

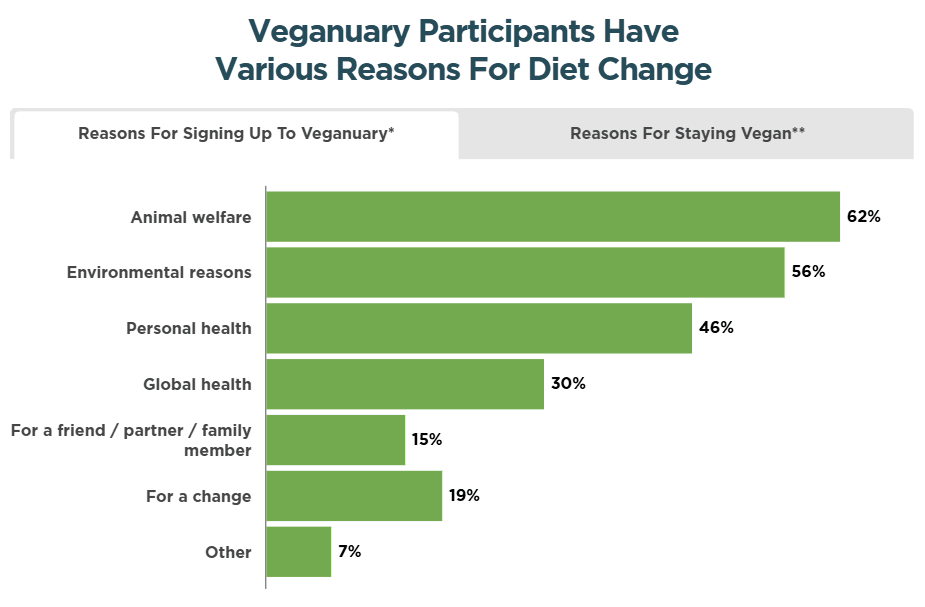

- Challenge participants have many motivations, including animal welfare, climate, health, and more. No one message will work on everybody – we need diversity in outreach campaigns.

- Challenges will likely work best if they target communities, not just individuals. This builds on growing research that diet change is easier in groups than solo efforts.

A few caveats here: I didn't conduct cost-effectiveness research at this stage (but I might look into it in future versions of this resource). It's possible that the most effective challenges are also the most expensive, as they might result in specific community-based approaches (such as assigning participants to mentors or creating personalized resources) that are harder to scale up. I'm not sure if that's true, but it's worth looking into.

Secondly, like with all interventions, we need to be thinking of vegan challenges as working in conjunction with other tactics. For example, we can consider hosting documentary screenings in a community that is immediately followed up by a local vegan challenge; the pair of interventions are likely more powerful than the sum of their parts. This pairing of interventions is crucial for advocates to consider when choosing which strategies to enact or fund.

If you're curious about this intervention, I recommend reading the full resource linked above. What do you think about these ideas?

You can read them here! Impact of 10 Weeks to Vegan