This post summarizes a new meta-analysis from the Humane and Sustainable Food Lab. We analyze the most rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that aim to reduce consumption of meat and animal products (MAP). We conclude that no theoretical approach, delivery mechanism, or persuasive message should be considered a well-validated means of reducing MAP consumption. By contrast, reducing consumption of red and processed meat (RPM) appears to be an easier target. However, if RPM reductions lead to more consumption of chicken and fish, this is likely bad for animal welfare and doesn’t ameliorate zoonotic outbreak or land and water pollution. We also find that many promising approaches await rigorous evaluation.

This post updates a post from a year ago. We first summarize the current paper, and then describe how the project and its findings have evolved.

What is a rigorous RCT?

We operationalize “rigorous RCT” as any study that:

- Randomly assigns participants to a treatment and control group

- Measures consumption directly -- rather than (or in addition to) attitudes, intentions, or hypothetical choices -- at least a single day after treatment begins

- Has at least 25 subjects in both treatment and control, or, in the case of cluster-assigned studies (e.g. university classes that all attend a lecture together or not), at least 10 clusters in total.

Additionally, studies needed to intend to reduce MAP consumption, rather than (e.g.) encouraging people to switch from beef to chicken, and be publicly available by December 2023.

We found 35 papers, comprising 41 studies and 112 interventions, that met these criteria. 18 of 35 papers have been published since 2020.

The main theoretical approaches:

Broadly speaking, studies used Persuasion, Choice Architecture, Psychology, and a combination of Persuasion and Psychology to try to change eating behavior.

Persuasion studies typically provide arguments about animal welfare, health, and environmental welfare reasons to reduce MAP consumption. For instance, Jalil et al. (2023) switched out a typical introductory economics lecture for one on the health and environmental reasons to cut back on MAP consumption, and then tracked what students ate at their college’s dining halls. Animal welfare appeals often used materials from advocacy organizations and were often delivered through videos and pamphlets. Most studies in our dataset are persuasion studies.

Choice architecture studies change aspects of the contexts in which food is selected and consumed to make non-MAP options more appealing or prominent. For example, Andersson and Nelander (2021) randomly alter whether the vegetarian option occurs on the top of a university cafeteria’s billboard menu or not. Choice architecture approaches are very common in food research, but only two papers met our inclusion criteria; hypothetical outcomes and/or immediate measurement were common reasons for exclusion.

Psychology studies manipulate the interpersonal, cognitive, or affective factors associated with eating MAP. The most common psychological intervention is centered on social norms seeking to alter the perceived popularity of non-MAP dishes, e.g. two studies by Gregg Sparkman and colleagues. In another study, a university cafeteria put up signs stating that “[i]n a taste test we did at the [name of cafe], 95% of people said that the veggie burger tasted good or very good!” One study told participants that people who ate meat are more likely to endorse social hierarchy and embrace human dominance over nature. Other psychological interventions include response inhibition training, where subjects are trained to avoid responding impulsively to stimuli such as unhealthy food, and implementation intentions, where participants list potential challenges and solutions to changing their own behavior.

Finally, some studies combine persuasive and psychological messages, e.g. putting up a sign about how veggie burgers are popular along with a message about their environmental benefits, or pairing reasons to cut back on MAP consumption with an opportunity to pledge to do so.

Results: consistently small effects

We convert all reported results to a measure of standardized mean differences (SMD) and meta-analyze them using the robumeta package in R. An SMD of 1.0 indicates an average change equal to one standard deviation in the outcome.

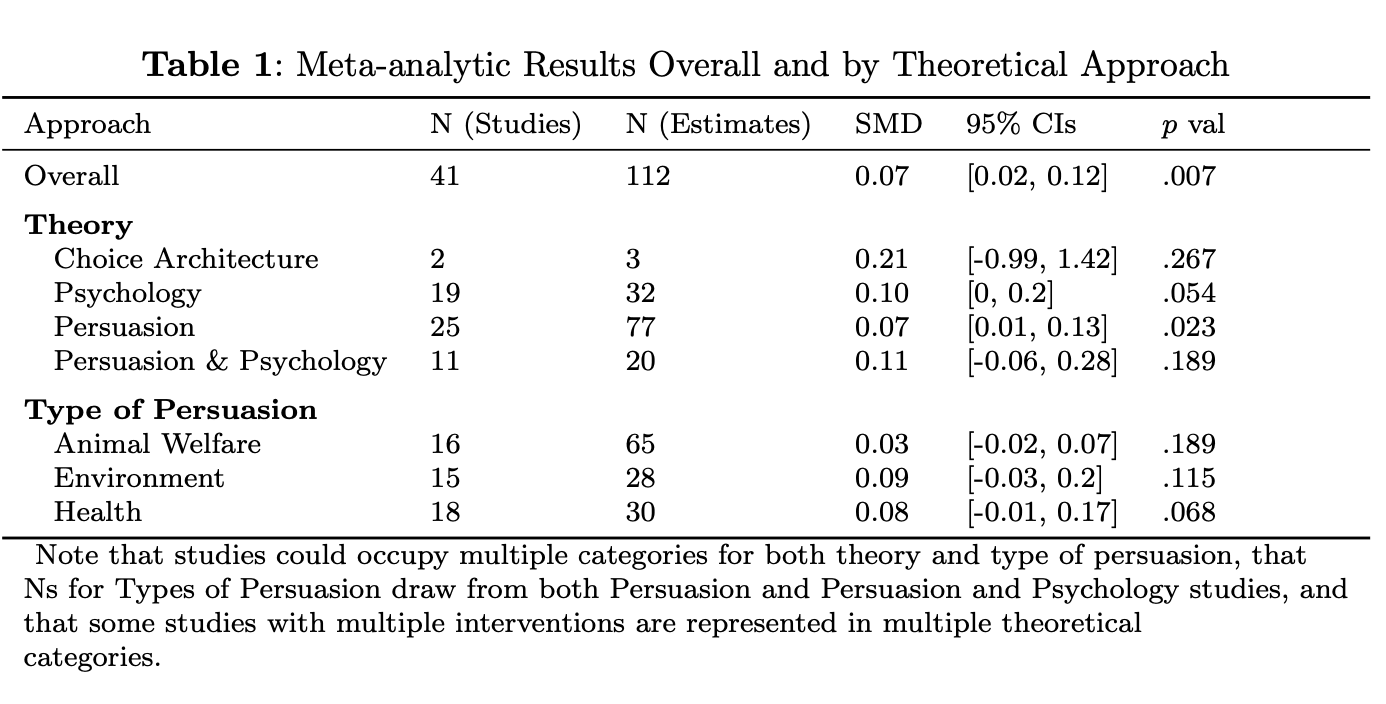

Our overall pooled estimate is SMD = 0.07 (95% CI: [0.02, 0.12]). Table 1 displays effect sizes separated by theoretical approach and by type of persuasion.

Most of these effect sizes and upper confidence bounds are quite small. The largest effect size, which is associated with choice architecture, comes from too few studies to say anything meaningful about the approach in general.

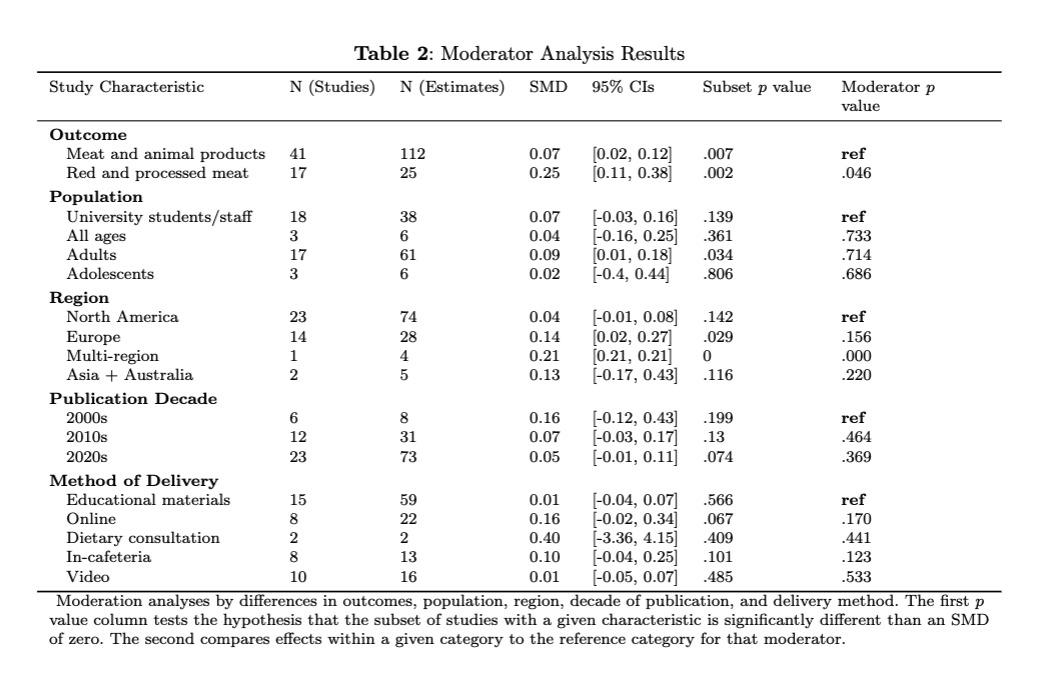

Table 2 presents results associated with different study characteristics.[1]

Probably the most striking finding here is the comparatively large effect size associated with studies aimed at reducing RPM consumption (SMD = 0.25, 95% CI: [0.11, 0.38]). We speculate that reducing RPM consumption is generally perceived as easier and more socially normative than cutting back on all categories of MAP. (It’s not hard to find experts in newspapers saying things like: “Who needs steak when there’s... ried chicken?”)

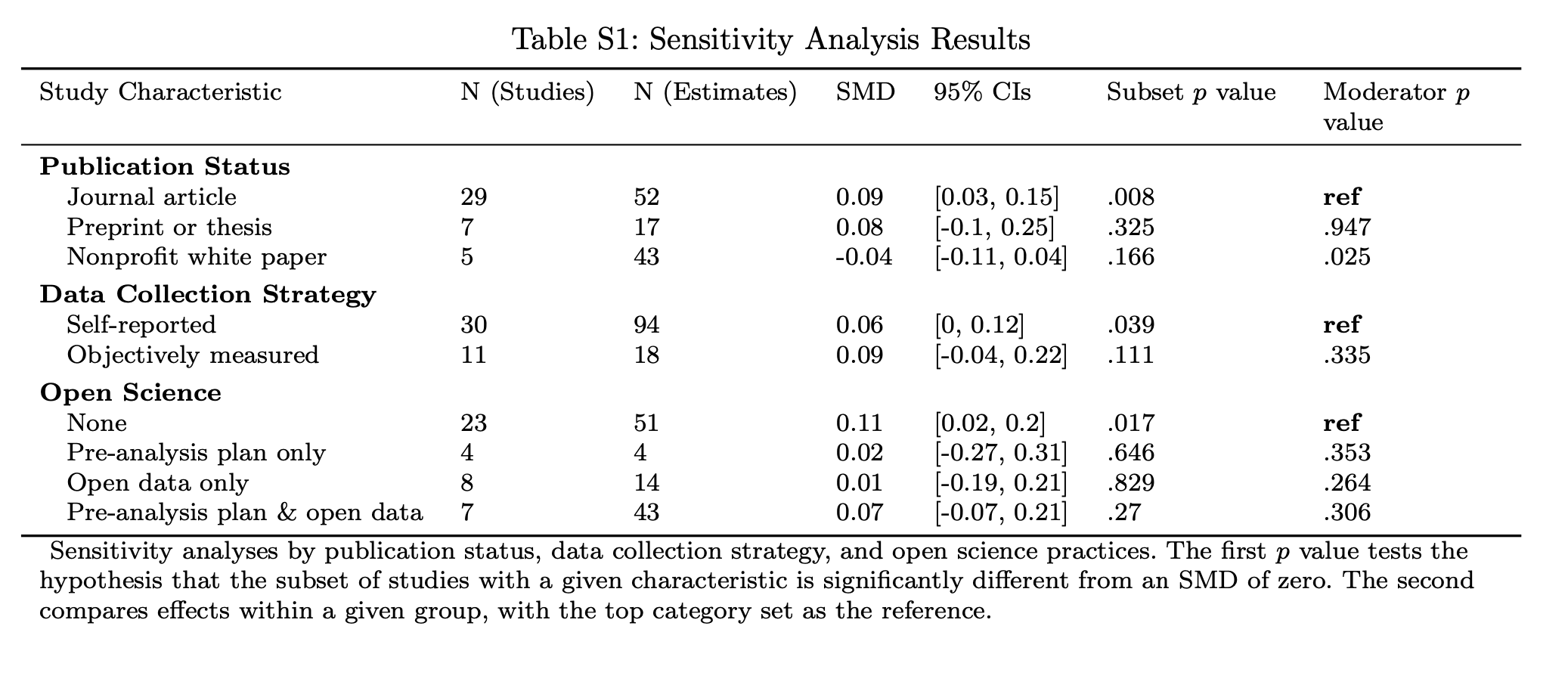

Likewise, when we integrate a supplementary dataset of 22 marginal studies, comprising 35 point estimates, that almost met our inclusion criteria, we find a considerably larger pooled effect: SMD = 0.2 (95% CI: [0.09, 0.31]). Unfortunately, this suggests that increased rigor is associated with smaller effect sizes in this literature, and that prior literature reviews which pooled a wider variety of designs and measurement strategies may have produced inflated estimates.

Where do we go from here?

In our experience, EAs generally accept that behavioral change, particularly around something as ingrained as meat, is a hard problem. But if you read the food literature in general, you get the impression that consumers are easily influenced by local cues and that their behaviors are highly malleable. In our view, a lot of that discrepancy comes down to measurement limitations in the literature. For example,. studies that set the default meal choice to be vegetarian at university events sometimes find large effects. But what happens at the next meal, or the day after? Do people eat more meat to compensate? For the most part, we don’t know, although it is definitely possible to measure delayed outcomes.

Likewise, we encourage researchers to distinguish reducing all MAP consumption and reducing just some particular category of it. RPM is of special concern for its environmental and health consequences, but if you care about animal welfare, a society-wide switch from beef to chicken is probably a disaster.

On a brighter note, we reviewed a lot of clever, innovative designs that did not meet our inclusion criteria, and we’d love to see these ideas implemented with more rigorous evaluation:

- Extended contact with farm animals

- Manipulations to the price of meat

- Activating moral and/or physical disgust

- Watching popular media such as the Simpsons episode “Lisa the Vegetarian” or the movie Babe

- Many categories of choice architecture intervention.

For more, see the paper, our supplement, and our code and data repository.

How has this project changed over time?

Our previous post, describing an earlier stage of this project, reported that environmental and health appeals were the most consistently effective at reducing MAP consumption. However, at that time, we were grouping RPM and MAP studies together. Treating them as separate estimands changed our estimates a lot (and pretty much caused the paper to fall into place conceptually).

Second, we’ve analyzed a lot more literature. In the data section of our code and data repository, you’ll see CSVs that record of all the studies we included in our main analysis; our RPM analysis; a robustness check of studies that didn’t quite make it; the 150+ prior reviews we consulted; and the 900+ studies we excluded.

Third, Maya Mathur joined the project, and Seth joined Maya’s lab (more on that journey here). Our statistical analyses, and everything else, improved accordingly.

Happy to answer any questions!

Acknowledgments. Thanks to Adin Richards, Alex Berke, Alix Winter, Anson Berns, Dan Waldinger, Hari Dandapani, Martin Gould, Martin Rowe, Matt Lerner, and Rye Geselowitz for comments on an early draft. Thanks to Jacob Peacock, Andrew Jalil, Gregg Sparkman, Joshua Tasoff, Lucius Caviola, Natalia Lawrence, and Emma Garnett for help with assembling the database and providing guidance on their studies.Thanks to Sofia Vera Verduzco for research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the NIH (grant R01LM013866), Open Philanthropy, and the Food Systems Research Fund (Grant FSR 2023-11-07).

- ^

The moderator value estimates should be interpreted non-causally because study characteristics were not randomly assigned.

Thanks so much for this very helpful post!

I'm a bit confused about your framing of the takeaway. You state that "reducing meat consumption is an unsolved problem" and that "we conclude that no theoretical approach, delivery mechanism, or persuasive message should be considered a well-validated means of reducing meat and animal product consumption." However, the overall pooled effects across the 41 studies show statistical significance w/ a p-value of <1%. Yes, the effect size is small (0.07 SMD) but shouldn't we conclude from the significance that these interventions do indeed work?

Having a small effect or even a statistically insignificant one isn't something EAs necessarily care about (e.g. most longtermism interventions don't have much of an evidence base). It's whether we can have an expected positive effect that's sufficiently cheap to achieve. In Ariel's comment, you point to a study that concludes its interventions are highly cost-effective at ~$14/ton of CO2eq averted. That's incredible given many offsets cost ~$100/ton or more. So it doesn't matter if the effect is 'small', only that it's cost-effective.

Can you help EA donors take the necessary next step? It won't be straightforward and will require additional cost and impact assumptions, but it'll be super useful if you can estimate the expected cost-effectiveness of different diet-change interventions (in terms of suffering alleviated).

Finally, in addition to separating out red meat from all animal product interventions, I suspect it'll be just as useful to separate out vegetarian from vegan interventions. It should be much more difficult to achieve persistent effects when you're asking for a lot more sacrifice. Perhaps we can get additional insights by making this distinction?

Hi Wayne,

Great questions, I'll try to give them the thoughtful treatment they deserve.

- We don't place much (any?) credence in the statistical significance of the overall result, and I recognize that a lot of work is being done by the word "meaningfully" in "meaningfully reducing." For us, changes on the order of a few percentage points -- especially given relatively small samples & vast heterogeneity of designs and contexts (hence our point about "well-validated" -- almost nothing is directly replicated out of sample in our database) -- are not the kind

... (read more)