At EA Global Boston last year I gave a talk on how we're in the third wave of EA/AI safety, and how we should approach that. This post contains a (lightly-edited) transcript and slides. Note that in the talk I mention a set of bounties I'll put up for answers to various questions—I still plan to do that, but am taking some more time beforehand to get the questions right.

Transcript and slides

Hey everyone. Thanks for coming. You're probably looking at this slide and thinking: "how to change a changing world? That's a weird title for a talk. Probably it's a kind of weird talk." And the answer is, yes, it is a kind of weird talk.

So what's up with this talk? Firstly, I am trying to do something a little unusual here. It's quite abstract. It's quite disagreeable as a talk. I'm trying to poke at the things that maybe we haven't been thinking enough about as a movement or as a community. I'm trying to do a "steering the ship" type thing for EA.

I don't want to make this too inside baseball or anything. I think it's going to be useful even if people don't have that much EA background. But this seems like the right place to step back and take stock and think: what's happened so far? What's gone well? What's gone wrong? What should we be doing?

So the structure of the talk is:

- Three waves of EA and AI safety. (I mix these together because I think they are pretty intertwined, at least intellectually. I know a lot of people here work in other cause areas. Hopefully this will still be insightful for you guys.)

- Sociopolitical thinking and AI. What are the really big frames that we need as a community to apply in order to understand the way that the world is going to go and how to actually impact it over the next couple of decades?

There's a thing that sometimes happens with talks like this—maybe status regulation is the word. In order to give a really abstract big picture talk, you need to be super credible because otherwise it's very aspirational. I'm just going to say a bunch of stuff where you might be like, that's crazy. Who's this guy to think about this? It's not really his job or anything. I mean, it kind of is my job, and part of it is my own framework, but a lot of it is reporting back from certain front lines. I get to talk to a bunch of people who are shaping the future or living in the future in a way that most of the world isn't. So part of what I'm doing here is trying to integrate those ideas from a bunch of people that I get to talk to and lay them out. Your mileage may vary.

Three waves of EA and AI safety

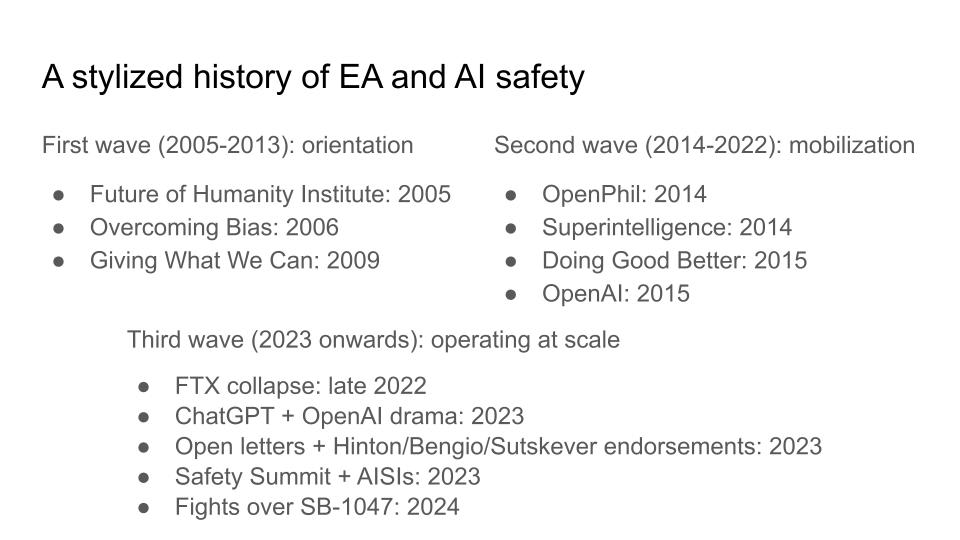

Let's start with a very stylized history of EA and AI safety. I'm going to talk about it in three waves. Wave number one I’ll say, a little arbitrarily, is 2005 to 2013. That's the orientation wave. This wave was basically about figuring out what was up with the world, introducing a bunch of big picture ideas. The Future of Humanity Institute, Overcoming Bias and LessWrong were primarily venues for laying out worldviews and ideas, and that was intertwined with Giving What We Can and the formation of the Oxford EA scene. I first found out about EA from a blog post on LessWrong back in 2010 or 2011 about how you should give effectively and then give emotionally separately.

So that was one wave. The next wave I'm going to call mobilization, and that's basically when things start getting real. People start trying to actually have big impacts on the world. So you have OpenPhil being spun out. You have a couple of books that are released around this time: Superintelligence, Doing Good Better. You have the foundation of OpenAI, and also around this time the formation of the DeepMind AGI safety team.

So at this point, there's a lot of energy being pushed towards: here's a set of ideas that matter. Let's start pushing towards these. I'm more familiar with this in the context of AI. I think a roughly analogous thing was happening in other cause areas as well. Maybe the dates are a little bit different.

Then I think the third wave is when things start mattering really at scale. So you have a point at which EA and AI safety started influencing the world as a whole on a macro level. The FTX collapse was an event with national and international implications, one of the biggest events of its kind. You had the launch of ChatGPT and various OpenAI dramas that transfixed the world. You had open letters about AI safety, endorsements by some of the leading figures in AI, safety summits, AI safety institutes, all of that stuff. It's no longer the case that EA and AI safety are just one movement that's just doing stuff off in its corner. This stuff is really playing out at scale.

To some extent this is true for other aspects of EA as well. A lot of other a lot of the key intellectual figures that are most prominent in American politics, people like Ezra Klein and Nate Silver and so on, really have been influenced by the worldview that was developed in this first wave and then mobilized in the second wave.

I think you need pretty different skills in order to do each of these types of things well. We’ve seen an evolution of what orientation you need to have in order to succeed at these types of waves, which to various extents we have or haven't had.

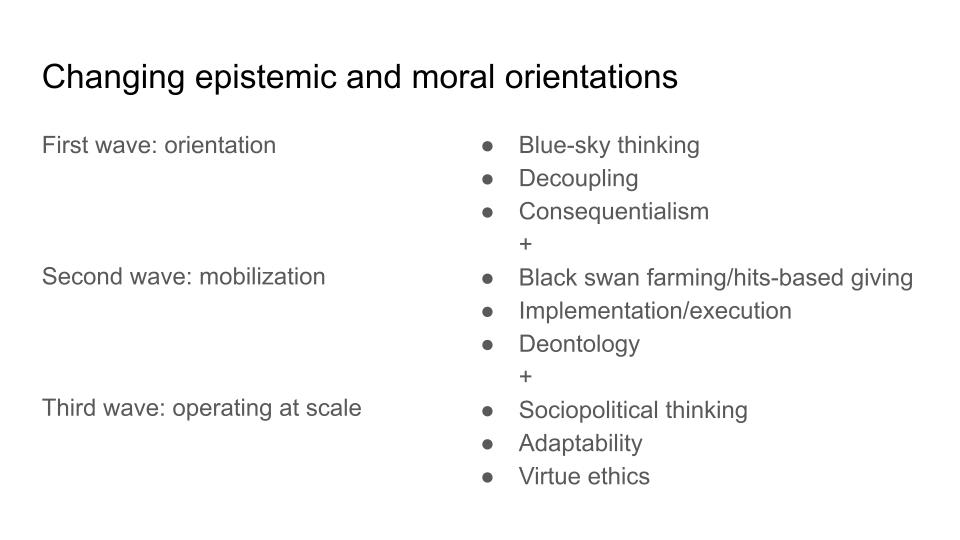

So for the first wave, it's thinking oriented. You need to be really willing to look beyond the frontiers of what other people are thinking about. You need to be high-decoupling. You're willing to transgress on existing norms or existing assumptions that people take for granted. And you want to be consequentialist. You want to think about what is the biggest impact I can have? What's the thing that people are missing? How can I scale?

As you start getting into the second wave, you need to add on another set of skills and orientations. One term for this in the startup context is black swan farming. Another term that OpenPhil has used is hits-based giving, the idea that you should really be optimizing for getting a few massive successes, and that's where most of your impact comes from. In order to do those massive successes well, you need the skill of implementation and execution. That's pretty different thing from sitting at an institute in Oxford thinking about the far future.

To do this well, I think the other thing you need is deontology. Because when you start actually doing stuff—when you start trying to scale a company, when you start trying to influence philanthropy—it's easy to see ways in which maybe you could lie a little bit. Maybe you can be a bit manipulative. In extreme cases, like FTX, it'd be totally deceitful. But even for people operating at much smaller scales, I think deontology here was one of the guiding principles that needed to be applied and in some cases was and in some cases wasn't.

Now we're in the third wave. What do we need for the third wave? I think it's a couple of things. Firstly, I think we can no longer think in terms of black swan farming or hit space giving. And the reason is that when you are operating at these very large scales, it's no longer enough to focus on having a big impact. You really need to make sure the impact is positive.

If you're trying to found a company, you want the company to grow as fast as possible. The downside is the company goes bust. That's not so bad. If you're trying to shape AI regulation, then you can have a massive positive impact. You can also have a massive negative impact. There's really a different set of mindset and set of skills required.

You need adaptability because on the timeframe that you might build a company or start a startup or start a charity, you can expect the rest of the world to remain fixed. But on the timeframe that you want to have a major political movement, on the timeframe that you want to reorient the U.S. government's approach to AI, a lot of stuff is coming at you. The whole world is, in some sense, weighing in on a lot of the interests that have historically been EA's interests.

And then thirdly, I think you want virtue ethics. The reason I say this is because when you are operating at scale, deontology just isn't enough to stop you from being a bad person. If you're operating a company, maybe you commit some fraud, as long as you don't step outside the clear lines of what's legal and what's moral, then people kind of expect that maybe you use shady business tactics or something.

But when you're a politician and you're being shady you can screw a lot of stuff up. When you're trying to do politics, and when you're in domains that have very few clear, bright lines, it's very hard to say you crossed a line here because it's all politics. The way to do this in a high integrity way that leads to other people wanting to work with you is really to focus on doing the right things for the right reasons. I think that's the thing that we need to have in order to operate at scale in this world.

So what does it look like to fuck up the third wave? The next couple of slides are deliberately a little provocative. You should take them 80% of how strongly I say them, and in general, maybe you should take a lot of the stuff I say 80% of how seriously I say it, because I'm very good at projecting confidence.

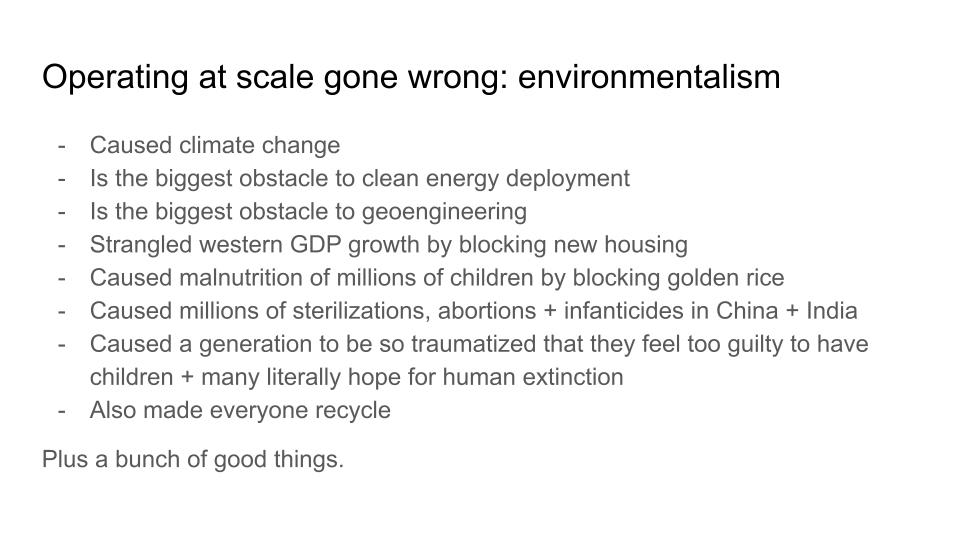

But I claim that one of the examples where operating at scale is just totally gone to shit is the environmentalist movement. I would somewhat controversially claim that by blocking nuclear power, environmentalism caused climate change. Via the Environmental Protection Act, environmentalism caused the biggest obstacle to clean energy deployment across America. Via opposition to geoengineering, it's one of the biggest obstacles to actually fixing climate change. The lack of growth of new housing in Western countries is one of the biggest problems that's holding back Western GDP growth and the types of innovation that you really want in order to protect the environment.

I can just keep going down here. I think the overpopulation movement really had dramatically bad consequences on a lot of the developing world. The blocking of golden rice itself was just an absolute catastrophe.

The point here is not to rag on environmentalism. The point is: here's a thing that sounds vaguely good and kind of fuzzy and everyone thinks it's pretty reasonable. There are all these intuitions that seem nice. And when you operate at scale and you're not being careful, you don't have the types of virtues or skills that I laid out in the last slide, you just really fuck a lot of stuff up. (I put recycling on there because I hate recycling. Honestly, it's more a symbol than anything else.)

I want to emphasize that there is a bunch of good stuff. I think environmentalism channeled a lot of money towards the development of solar. That was great. But if you look at the scale of how badly you can screw these things up when you're taking a mindset that is not adapted to operating at the scale of a global economy or global geopolitics, it's just staggering, really. I think a lot of these things here are just absolute moral catastrophes that we haven't really reckoned with.

Feel free to dispute this in office hours, for example, but take it seriously. Maybe I want to walk back these claims 20% or something, but I do want to point at the phenomenon.

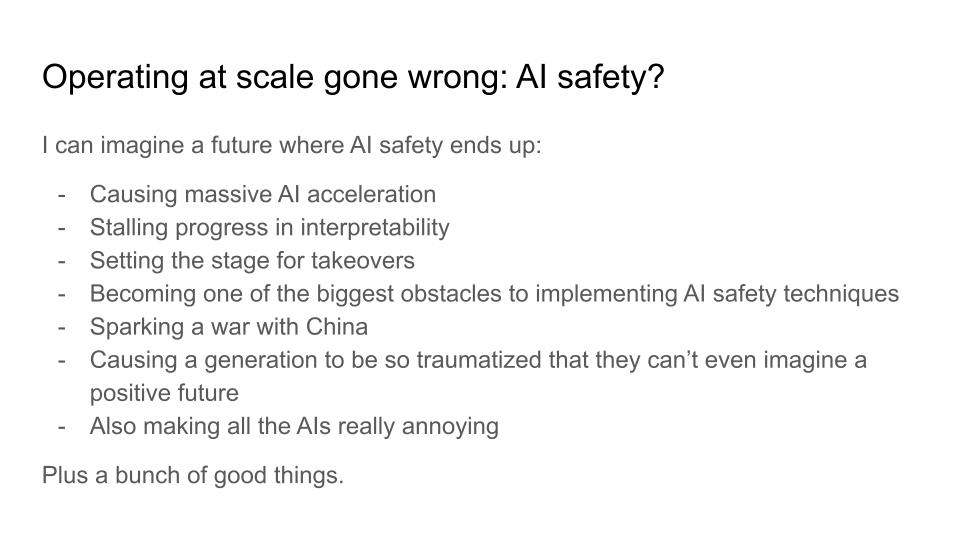

And then I want to say: okay, what if that happens for us? I can kind of see that future. I can kind of picture a future where AI safety causes a bunch of harms that are analogous to this type of thing:

- Causing massive AI acceleration (insofar as you think that's a harm).

- If you block open source, plausibly it stalls a bunch of progress on interpretability.

- If you centralize power over AI, then maybe that sets the stage itself for AI takeover.

- If you regulate AI companies in the wrong ways, then maybe you become one of the biggest obstacles to implementing AI safety techniques.

- If you pass a bunch of safety legislation that actually just adds on too much bureaucracy. Europe might just not be a player in AI because they just can't have startups forming partly because of things like the EU AI Act.

- The relationship of the U.S. and China, it's a big deal. I don't know what effect AI safety is going to have on that, but it's not clearly positive.

- Making AI really annoying—that sucks.

The thing I want to say here is I really do feel a strong sense of: man, I love the AI safety community. I think it's one of the groups of people who have organized to actually pursue the truth and actually push towards good stuff in the world more than almost anyone else. It's coalesced in a way that I feel a deep sense of affection for. And part of what makes me affectionate is precisely the ability to look at stuff like this and be like: okay, what do we do better?

All of these things are operating at such scale, what do we actually need to do in order to not accidentally screw up as badly as environmentalism (or your example of choice if you don't believe that particular one)?

Note: I plan to post these bounties separately, but am taking some more time beforehand to get the questions right.

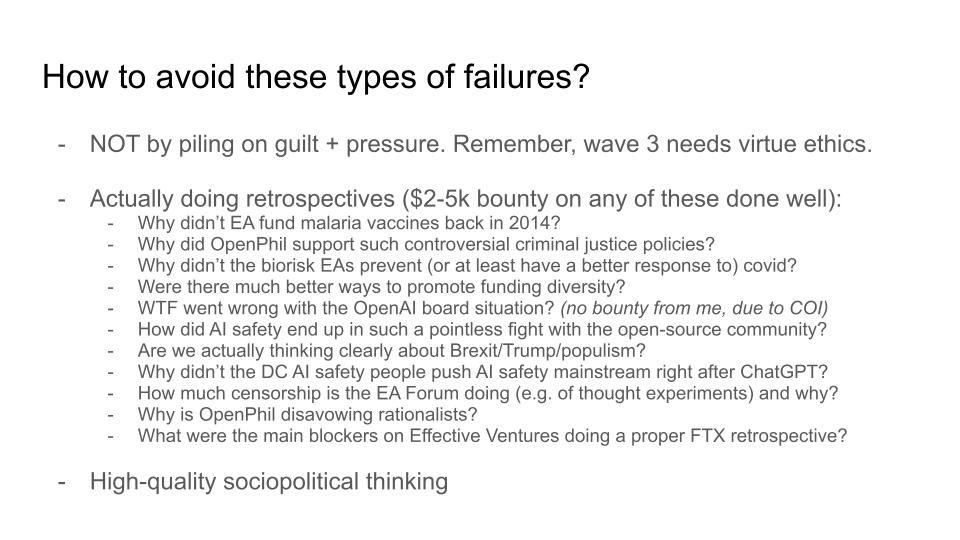

So do I have answers? Kind of. These are just tentative answers and I'll do a bit more object-level thinking later. This is the more meta element of the talk. There's one response: oh, boy, we better feel really guilty whenever we fuck up and apply a lot of pressure to make sure everyone's optimizing really hard for exactly the good things and exclude anyone who plausibly is gonna skew things in the wrong direction.

And I think this isn't quite right. Maybe that works at a startup. Maybe it works at a charity. I don't think it works in Wave 3, because of the arguments I gave before. Wave 3 needs virtue ethics. You just don't want people who are guilt-ridden and feeling a strong sense of duty and heroic responsibility to be in charge of very sensitive stuff. There's just a lot of ways that that can go badly. So I want to avoid that trap.

I want to have a more grounded view. These are hard problems to solve. And also, we have a bunch of really talented people who are pretty good at solving problems. We just need to look at them and start to think things through.

Here's a list of questions that I often ask myself. I don't really have time to answer a lot of these questions: hey, here's a thing that we could have done better, have we actually written up the lessons from that? Can we actually learn from it as a community?

I'm going to put up a post on this about how I'll offer bounties for people who write these up well, maybe $2,000 to $5,000-ish on these questions. I won't go through them in detail, but there's just a lot of stuff here. I feel like I want to learn from experience, because there's a lot of experience that the community has aggregated across itself. And I think there's a lot of insight to be gained—not in a beating ourselves up way, not in a "man, we really screwed up the malaria vaccines back in 2014" way—but by asking: yeah, what was going on there? Malaria was kind of our big thing. And then malaria vaccines turned out to be a big deal. Was there some missing mental emotion that needed to happen there? I don't know. I wasn't really thinking about it at the time. Maybe somebody was. Maybe somebody can tell me later. And the same thing for all of these others.

The other thing I really want is high-quality sociopolitical thinking, because when you are operating at this large scale, you really need to be thinking about the levers that are moving the world. Not just the local levers, but what's actually going on in the world. What are the trends that are shaping the next decade or two decades or half century or century? EA is really good in some ways at thinking about the future, and in other ways, tends to abstract away a little too much. We think about the long-term future of AI, but the next 20 years of politics, somehow doesn't feel as relevant. So I'm going to do some sociopolitical thinking in the second half of this talk.

Sociopolitical thinking and AI

So here's part two of the talk: what's going on with the world? High-quality sociopolitical thinking, which is the sort of thing that can ground these large-scale Wave 3 actions, should be big picture, should be first principles, historically grounded insofar as you can. It’s pretty different from quantitative-type thinking that a lot of EAs are pretty good at. At first, the thing you're doing is trying to identify deep levers in the world, these sort of structural features of the world that other people haven't really noticed.

I will flag a couple of people who I think are really good at this. I think Friedman, talking about “The world is flat”; Fukuyama, talking about “The end of history”. Maybe they're wrong, maybe they're right, but it's a type of thinking that I want to see much more of. Dominic Cummings: whether you like him or you hate him, he was thinking about Brexit just at a deeper level than basically anyone else in the world. Everyone else was doing the economic debate about Brexit, and he was thinking about the sociocultural forces that shape nations on the time frame of centuries or decades. Maybe he screwed it up, maybe you didn't, but at the very least you want to engage with that type of thinking in order to actually understand how radical change is going to play out over the next few decades.

I am going to, in the rest of this talk, just tell you my two-factor model of what's going on with the world. And this is the bit where I'm definitely going a long way outside my domain of expertise, definitely this is just way bigger than it is all plausible for a two-factor model to try and do. So don't believe what I'm saying here, but I want to have people tell me that I'm being an idiot about this. I want you to do better than this. I want to engage with alternative conceptions of how to make sense of the world as a whole in such a way that we can then slot in a bunch of more concrete interventions like AI safety interventions or global health interventions or whatever.

Okay, here's my two-factor model. I want to understand the world in terms of two things that are happening right now:

- Technology dramatically increases returns to talent.

- Bureaucracy is eating the world.

In order to understand these two drivers of change, you can't just look at history because we are in the middle of these things playing out. These are effects that are live occurrences and we're in some sense at the peak of both of them. What do I mean by these?

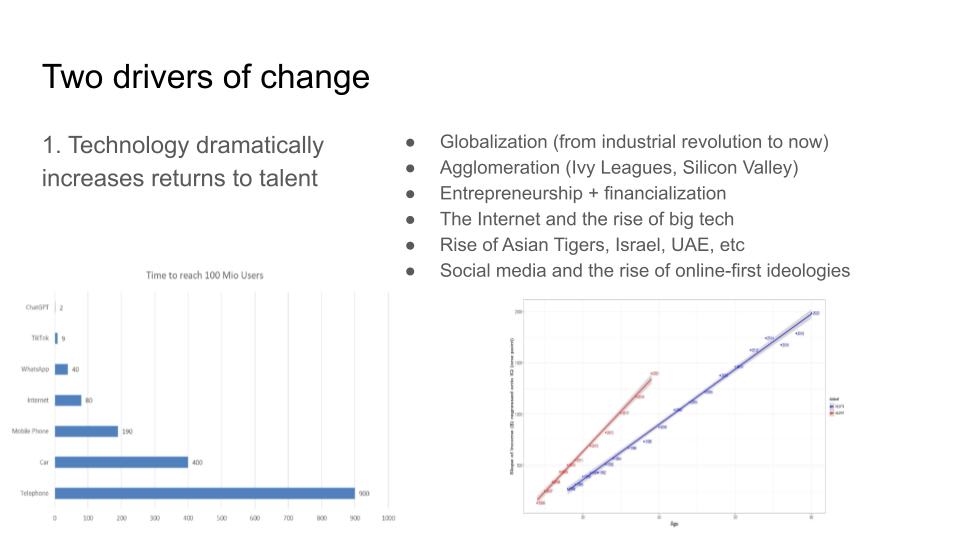

Number one, technology dramatically increases returns to talent. You should be thinking in terms of centuries. You can think about globalization from the Industrial Revolution, from colonialism. It used to be the case that no matter how good you were—no matter how good you were at inventing technology, no matter how good you were at politics—you could only affect your country, or as far as your logistics and supply chains reached.

And then it turned out that innovators in Britain, for example, could affect the rest of the world, for good or bad. This has played out gradually over time. It used to take a long time for exceptional talent to influence the world. It now takes much less time. So this graph on the left here is a chart of how long it took to get to 100 million users for different innovations. The telephone is at the bottom. That took a long time. I think it's 900 months down there. The car, the mobile phone, the internet, different social media. At the top, you see this tiny little thing that's ChatGPT. It's basically invisible how quickly it got to 100 million users. So if you can do something like that, if you can invent the telephone, if you can invent ChatGPT or whatever, the returns to being good enough to do that accumulate much faster and at much larger scales than they used to.

This is what you get with the agglomeration of talent in the Ivy Leagues and Silicon Valley. I think Silicon Valley right now is maybe the greatest agglomeration of talent in the history of humanity. That’s a bit of a self-serving claim because I live there, but I think it's just also true. And it's a weird perspective to have because something like this has never happened before. It has never been the case that you have a pool of so many people from across the world to draw on to get a bunch of talent in one place. In some sense it makes a lot of sense that this effect is driving a lot of unusual and unprecedented sociopolitical dynamics, as I'll talk about shortly.

The other graph here is an interesting one. It's the financial returns to IQ over two cohorts. The blue line is the older cohort, it's from 50 years ago or something. It's got some slope. And then the red line is a newer cohort. And that's a much steeper slope. What that means is basically for every extra IQ point you have, in the new cohort you get about twice as much money on average for that IQ point. That's a particularly interesting illustration of the broader base of technology increasing returns to talent.

Then we can quibble about whether or not it's precisely technology driving that. But I think it's intuitively compelling that if you’re an engineer at Google and you can make one change that is immediately rolled out to a billion people, of course being better at your job is gonna have these huge returns. Obviously the tech itself is unprecedented, but I think one way in which we don't think about it being unprecedented is that the ability to scale talent is just absurd. (I won’t say specific anecdotes of how much people are being headhunted for, but it's kind of crazy.)

Even people being in this room is an example of this technology dramatically increasing returns to talent. There's a certain ability to read ideas on the internet and then engage with them and then build a global community around them that just wouldn't have been possible even 50 years ago. It would have just been way harder to have a community that spans England and the East Coast and the West Coast and get people together in the same room. It's nuts, and now you can actually do that.

I should say the best example of this, which is obviously just crazy good entrepreneurs. If you were just the best in the world at the thing you do, then now you can make $100 billion. Not reliably, but Elon started a lot of companies and he just keeps succeeding because he is the best in the world at entrepreneurship.He couldn't previously have made $200 billion from that, and now he can. And the same is true for other people in this broad space. And so I should especially highlight that the returns are extreme at the extreme outlier ends of the talent scale.

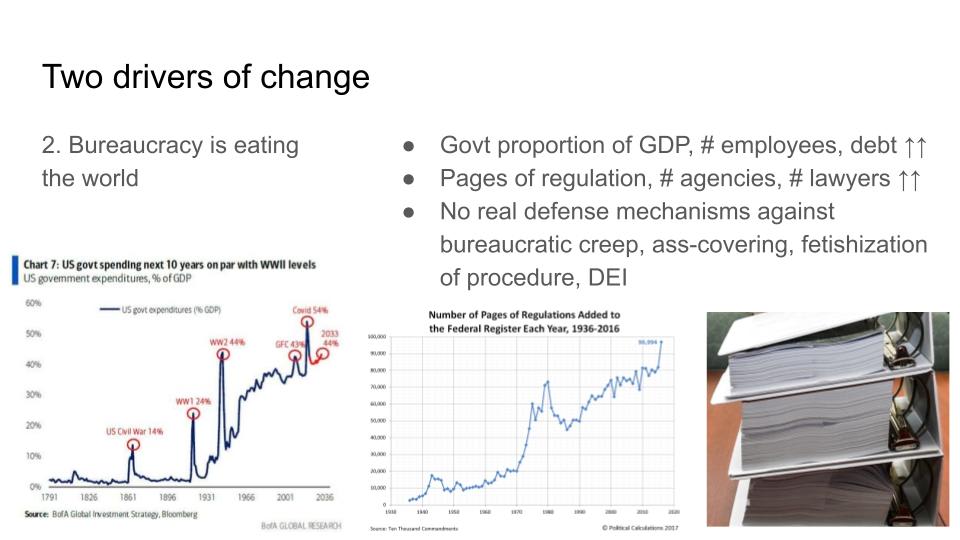

Second driver: bureaucracy is eating the world. You might say: sure there are all these returns to talent, but people used to get a lot of stuff done and now they can't. So the counterpoint to this, or the opposing force, is that there's just way more bureaucracy than there used to be. And this is true of the spending of governments across the world—this is the U.S. government spending as a proportion of GDP, and you can see these ratchet effects where it goes up and it just never goes back down again. And now it's at this crazy level of what, 50% or something?

So if you just look at the number of employees of the government [EDIT: this one is incorrect], the amount of debt that Western governments have… This graph here of pages of regulation, that's not even the total amount of regulation, that's the amount of regulation added per year. So if that's linearly increasing, then the actual amount of regulation is quadratically increasing. It's kind of nuts. The picture here is just one environmental review for one not even particularly important policy—I think it was congestion pricing—it took three years and then ultimately got vetoed anyway.

Libertarians have always talked about “there's too much regulation”, but I think it's underrated how this is not a fact about history, this is a thing we are living through—that we are living through the explosion of bureaucracy eating the world. The world does not have defense mechanisms against these kinds of bureaucratic creep. Bureaucracy is optimized for minimizing how much you can blame any individual person. So there's never a point at which the bureaucracy is able to take a stand or do the sensible policy or push back even against stuff that's blatantly illegal, like a bunch of the DEI stuff at American universities. It’s just really hard to draw a line and be like “hey, we shouldn't do this illegal thing”. Within a bureaucracy, nobody does it. And you have multitudes of examples.

So these are two very powerful forces that I think of as shaping the world in a way that they didn't 20 or 40 or 60 years ago.

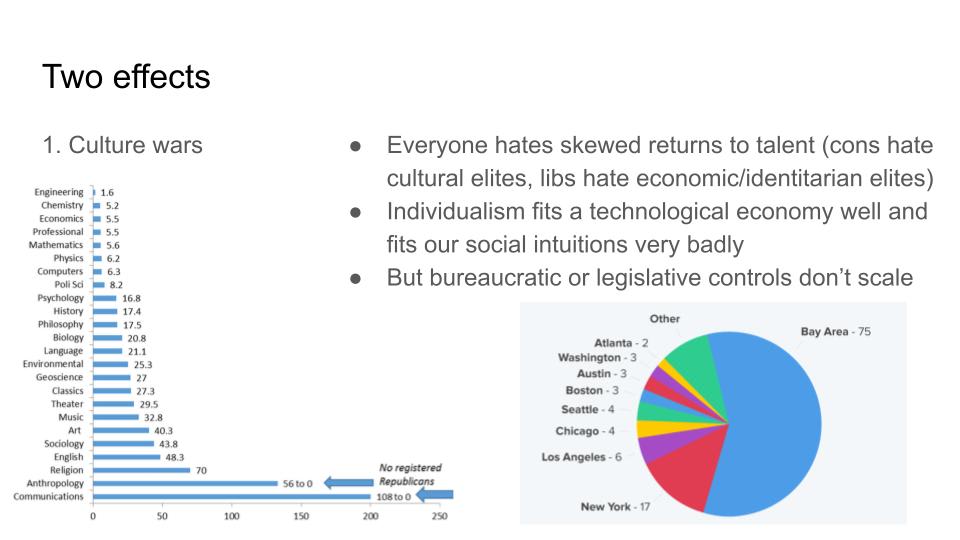

This will get back to more central EA topics eventually, but I'm trying to flesh out some of the ways in which I apply this lens or paradigm. One of them is culture wars. The thing about culture wars is that everyone really hates the extent to which the returns to talent are skewed towards outliers, but they hate it in different ways. Liberals hate economic and identitarian elites—the fact that one person can accumulate billions of dollars or that there are certain groups that end up outperforming and getting skewed returns. On the left, it's a visceral egalitarian force that makes them hate this.

On the right, I think a lot of conservatives and a lot of populist backlash are driven by the fact that the returns to cultural elitism are really high. There's just the small group of people in most Western countries—city elites, urban elites, coastal elites, whatever you want to call them—that can shape the culture of the entire country. And that's a pretty novel phenomenon. It didn't used to be the case that newspapers were so easily spread across literally the entire country—that the entirety of Britain is run so directly from London—that you have all the centralization in these cultural urban elites.

And one way you can think about the culture war is both sides are trying to push back on these dramatic returns to talent and both are just failing. The sort of controls that you might try and apply—the ways you might try and apply bureaucracy or apply legislation to even the playing field—just don’t really work. On both sides, people are in some sense helpless to push back on this stuff. They’re trying, they're really trying. But this is one of the key drivers of a lot of the cultural conflicts that we're seeing.

The graphs here on the left, we have the skew and political affiliation of university professors by different fields. Right at the top, I think that's like five to one, so even the least skewed are still really Democrat skewed. And then at the bottom, it's incredibly skewed to the point where there's no Republicans. This is the type of skewed returns to talent or skewed concentration of power that the right wing tends to hate.

And then on the right, you have the proportion of startups distributed across different cities in America. They do tend to agglomerate really hard, and there's just not that much you can do about it. Just because the returns to being in the number one best place in the world for something are just so high these days.

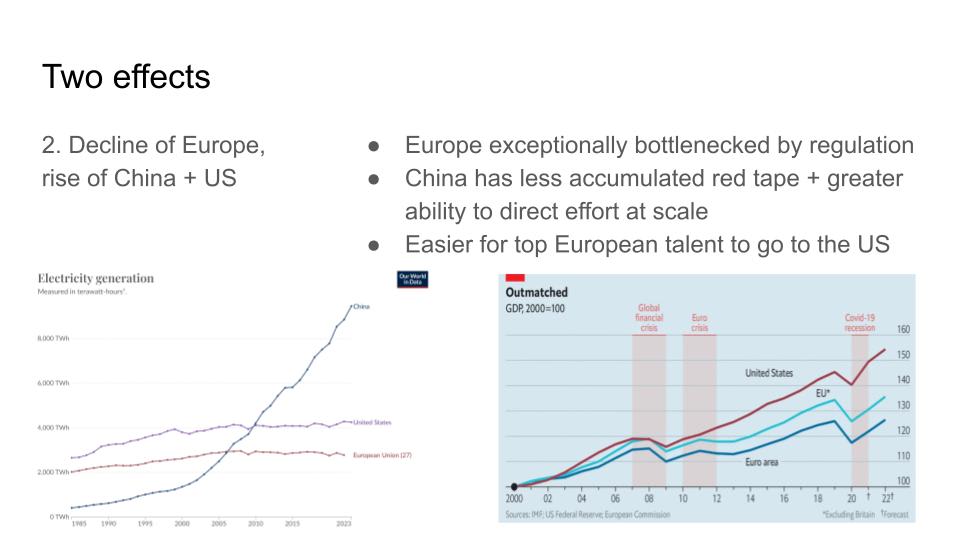

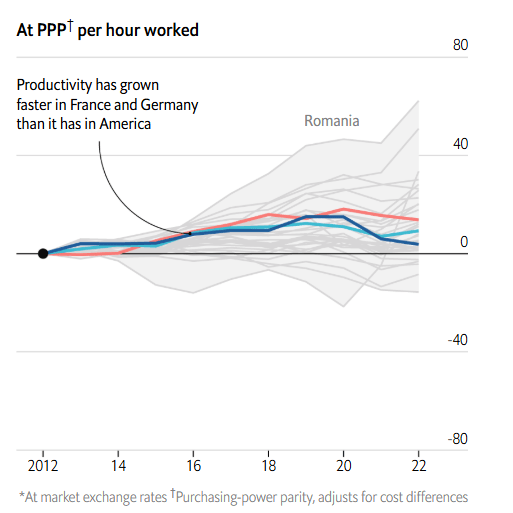

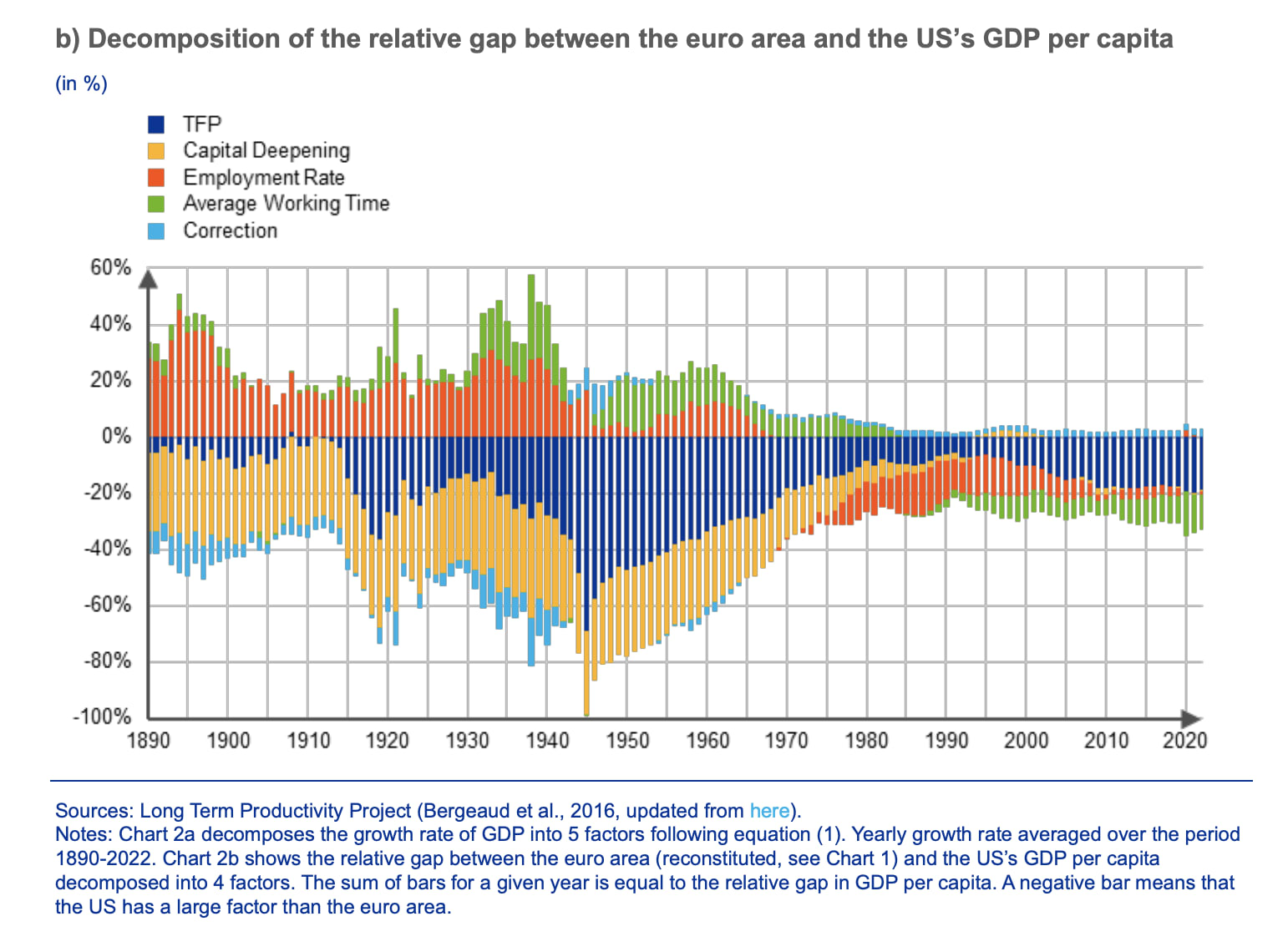

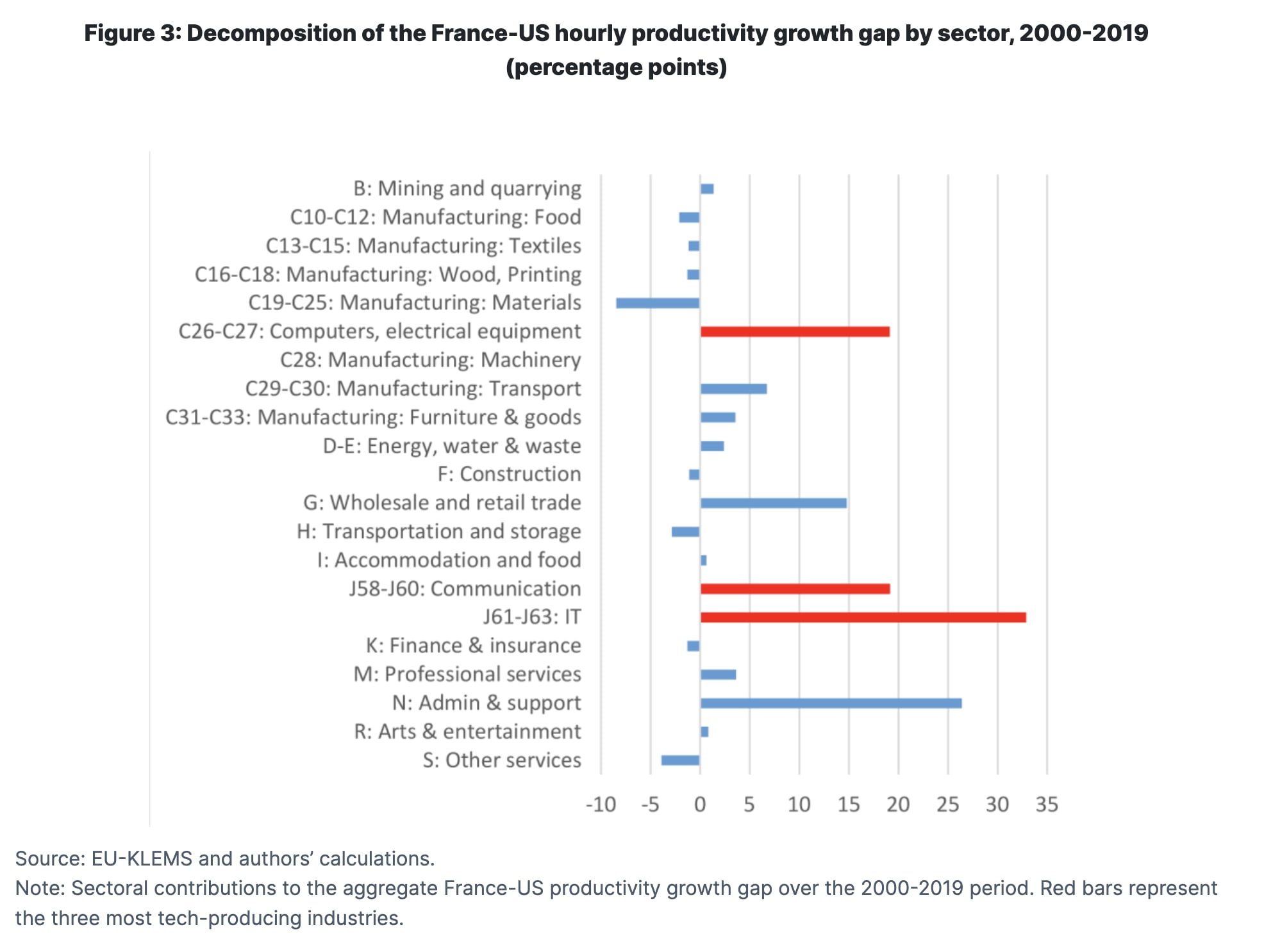

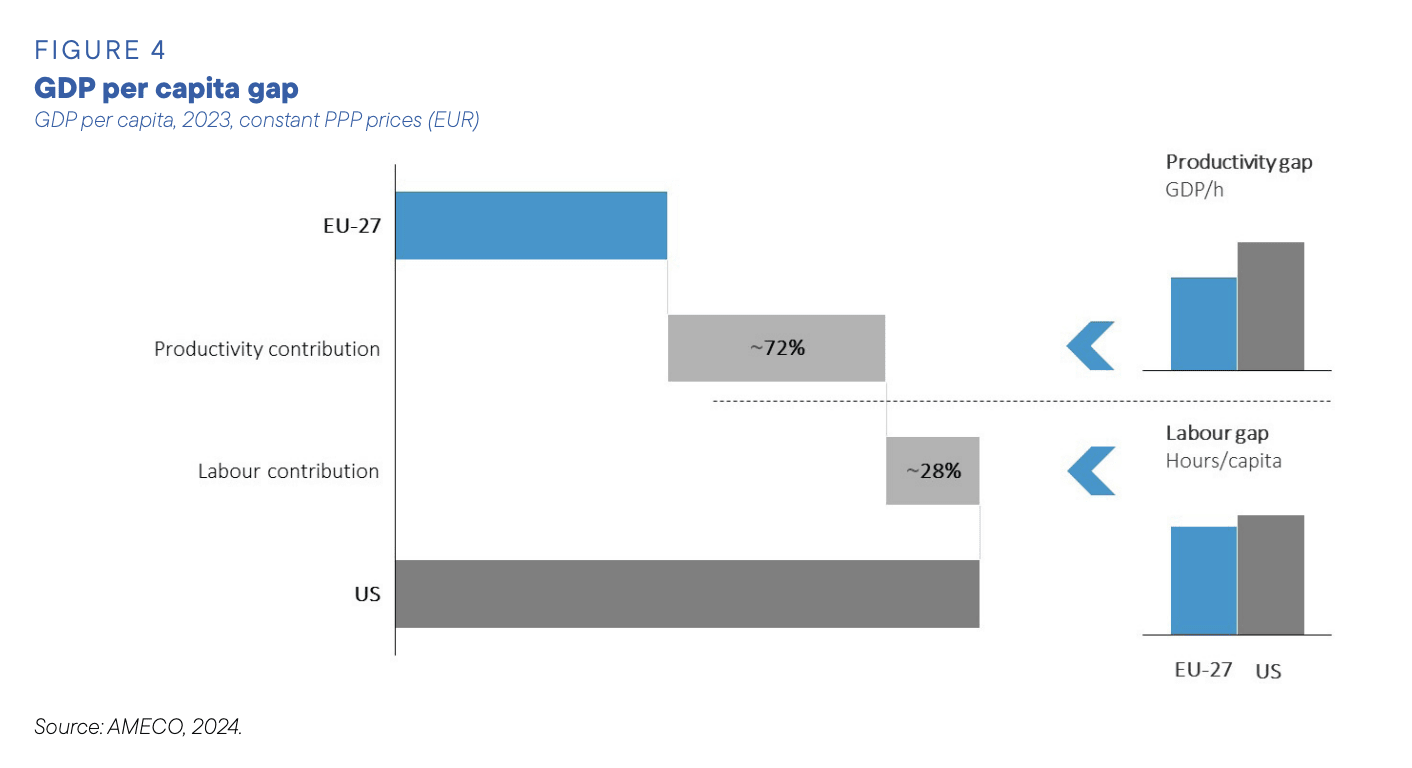

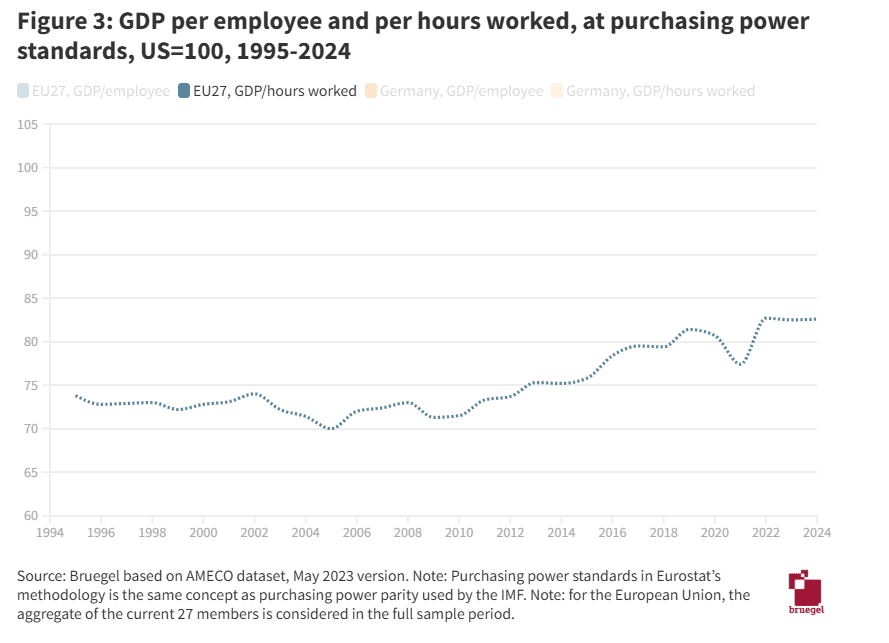

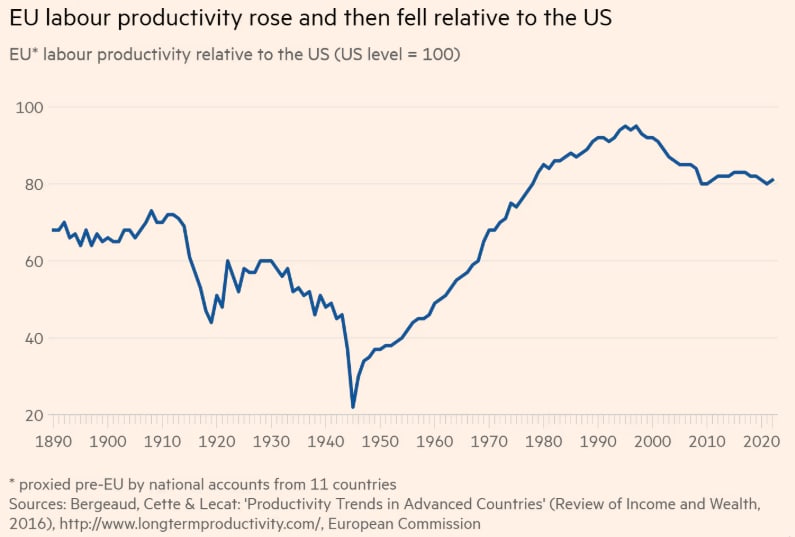

Second effect: I'll just talk through this very briefly, but I do think it's underrated how much the U.S. has overtaken the EU over the last decade or two decades in particular. You can see on the right, you have this crazy graph of U.S. growth being twice as high as European growth over the last 20 years. And I do think that it's basically down to regulation. I think the U.S. has a much freer regulatory environment, much more room to maneuver. In some countries in Europe, it's effectively illegal to found a startup because you have to jump through so many hoops, and the system is really not set up for that. In the U.S. at the very least, you have arbitrage between different states.

Then you have more fundamental freedoms as well. This is less a question of tax rates and more just a question of how much bureaucracy you have to deal with. But then conversely: why does the U.S. not have that much manufacturing? Why is it falling behind China in a bunch of ways? It's just really hard to do a lot of stuff when your energy policy is held back by radical bureaucracy. And this is basically the case in the U.S. The U.S. could have had nuclear abundance 50, 60 years ago. The reason that it doesn't have nuclear abundance is really not a technical problem, it's a regulation problem [which made it] economically infeasible to get us onto this virtuous cycle of improving nuclear. You can look at the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) standard for nuclear safety: basically no matter what the price, you just need to make nuclear safer. And that totally fucks the U.S.'s ability to have cheap energy, which is the driver of a lot of economic growth.

Okay. That was all super high level. I think it's a good framework in general. But why is it directly relevant to people in this room? My story here is: the more powerful AI gets, the more everyone just becomes an AI safety person. We've kind of seen this already: AI has just been advancing and over time, you see people falling into the AI safety camp with metronomic predictability. It starts with the most prescient and farsighted people in the field. You have Hinton, you have Bengio and then Ilya and so on. And it's just ticking its way through the whole field of ML and then the whole U.S. government, and so on. By the time AIs have the intelligence of a median human and the agency of a median human, it's just really hard to not be an AI safety person. So then I think the problem that we're going to face is maybe half of the AI safety people are fucking it up and we don't know which half.

And you can see these two effects that I described [as corresponding to two conflicting groups in AI safety]. Suppose you are really worried about technology increasing the returns to talent—for example, you're really worried that anyone could produce bioweapons in the future. It used to be the case that you had to be one of the best biology researchers in the world in order to actually improve bioweapons. And in the future, maybe anyone with an LLM can do it. I claim people start to think of AI risk as basically anarchy. You have this offense defense balance that's skewed towards people being able to mess up the world because AI will give a small group of people—a small group of terrorists, a small group of companies—the ability to have these massive effects that can't be controlled.

So the natural response to this frame on AI risk is you want to prevent it with central control. You want to make sure that no terrorists get bioweapon-capable AIs. You want to make sure that you have enough regulation to oversee all the companies and so on and so forth. Broadly speaking, this is the approach that resonates the most with Democrats and East Coast elites. Because they've been watching Silicon Valley, these crazy returns to talent, the fact that one engineer at Facebook can now skew the news that's seen by literally the entire world.

And it's like: oh shit, we can't keep control of this. We have to do something about it. And that's part of why you see these increasing attempts to control stuff from the Democrats, and East Coast elites in general—Ivy League professors and the sort of people who inform Democrat policy.

The other side of AI safety is that you're really worried about bureaucracy eating the world. And if you're really worried about that, then a natural way of thinking about AI risk is that AI risk is about concentration of power. You have these AIs, and if power over them gets consolidated within the hands of a few people—maybe a few government bureaucrats, maybe a few countries, maybe a few companies—then suddenly you can have all the same centralized control dynamics playing out, but much easier and much worse.

Centralized control over the Facebook algorithm—sure, it can skew some things, but it's not very flexible. You can't do that much—at worst you can nudge it slightly in one direction or other, but it's pretty obvious. Centralized control of AI, what that gives you is the ability to very flexibly shape the way that maybe everyone in the entire country interacts with AI. So this is the Elon Musk angle on AI risk: AI risk is fundamentally a problem about concentration of power. Whereas a lot of AI governance people tend to think of it more like AI risk as anarchy. That's maybe why we've seen a lot of focus on bioweapons, because it's a central example of an AI risk that maps neatly onto this left-hand side.

So how do you prevent that? Well, if you're Elon or somebody who thinks similarly, you try and prevent it using decentralization. You’re like: man, we really don't want AI to be concentrated in the hands of a few people or to be concentrated in the hands of a few AIs. (I think both of these are kind of agnostic as to whether it's humans or AIs who are the misaligned agents, if you will.) And this is kind of the platform that Republicans now (and West Coast elites) are running on. It's this decentralization, freedom, AI safety via openness. Elon wants xAI to produce a maximally truth-seeking AI, really decentralizing control over information.

I think they both have reasonable points—both of these sides are getting at something sensible. Unfortunately, politics is incredibly polarized right now. And so it's just really hard to bridge this divide. One of my worries is that AI safety becomes as polarized as the Democrats and the Republicans currently are. You can imagine these two camps of AI safety people almost at war with each other.

I don't know how to prevent that right now. I have some ideas. There's social links you can use—people sitting down and trying to see each other's perspectives. But fundamentally, it's a really big divide and I see AI safety and maybe EA more generally as trying to have one foot on either side of this gap and being stretched more and more.

So my challenge to the people who are listening to this here or in the recording is: how do we bridge that? How do we make it so that both of these reasonable concerns of AI risk as anarchy and AI risk as concentration of power can be tackled in a way that everyone accepts as good?

You can think of the US Constitution as trying to bridge that gap. You want to prevent anarchy, but you also want to prevent concentration of power. And so you have this series of checks and balances. One of the ways we should be thinking about AI governance is as: how do we put in regulations that also have very strong checks and balances? And the bigger of a deal you think AI is going to be, the more like a constitution—the more robust—these types of checks and balances need to be. It can't just be that there's an agency that gets to veto or not veto AI deployments. It needs to be much more principled and much closer to something that both sides can trust.

That was a lot. Do I have more things to say here? Yeah, my guess is that most people in this room, or most people listening, instinctively skew towards the left side here. I instinctively, personally skew a bit more towards the right side. I just posted a thread on why I think it's probably better if the Republicans win this election on Twitter. So you can check that out—I think it might be going viral during this talk—if you want to get more of an instinctive sense for why the right side is reasonable. I think it's just a really hard problem. And this type of sociopolitical thinking that I've been trying to advocate for in this talk, that's the type of thinking that you need in order to actually bridge these hard-to-bridge gaps.

I don't have great solutions, so I'm gonna say a bunch of platitude-adjacent statements. The first one is this community should be really truth-seeking, much more than most political movements or most political actors, because that works in the long term.

I think it's led us to pretty good places so far and we want to keep doing it. In some sense if you're truth-seeking enough then you converge to alignment research anyway—I have this blog post on why alignment research is what happens if you're doing machine learning and you try to be incredibly principled about it, or incredibly scientific about it. So you can check out that post on LessWrong and various other places.

I also have a recent post on why history and philosophy of science is a really useful framework for thinking about these big picture questions and what would it look like to make progress on a lot of these very difficult issues, compared with being bayesian. I’m not a fan of bayesianism—to a weird extent it feels like a lot of the mistakes that the community has made have fallen out of bad epistemology. I'm biased towards thinking this because I'm a philosopher but it does seem like if you had a better decision theory and you weren't maximizing expected utility then you might not screw FTX up quite as badly, for instance.

On the principled mechanism design thing, the way I want to frame this is: right now we think about governance of AI in terms of taking governance tools and applying them to AI. I think this is not principled enough. Instead the thing we want to be thinking about is governance with AI— what would it look like if you had a set of rigorous principles that governed the way in which AI was deployed throughout governments, that were able to provide checks and balances. Able to have safeguards but also able to make governments way more efficient and way better at leveraging the power of AI to, for example, provide a neutral independent opinion like when there's a political conflict.

I don't know what this looks like yet, I just want to flag it as the right way to go. And I think part of the problems that people have been having in AI governance are that our options are to stop or to not stop because no existing governance tools are powerful enough to actually govern AI, it’s too crazy. And that’s true, but governing with AI opens up this whole new expanse of different possibilities I really want people to explore, particularly people who are thinking about this stuff in first-principles and historically informed ways.

That’s the fourth point here: EA and AI safety have been bad at that. I used the example of Dominic Cummings before as someone who is really good at that. So if you just read his stuff then maybe you get an intuition for the type of thinking that leads you to realize that there’s a layer of the Brexit debate deeper than what everyone else was looking at. What does that type of thinking lead you when you apply it to AI governance? I’ve been having some really interesting conversations in the last week in particular with people who are like: what if we think way bigger? If you really take AGI seriously then you shouldn’t just be thinking about historical changes on the scale of founding new countries, you should be thinking about historical changes on the scale of founding new types of countries.

I had a debate with a prominent AI founder recently about who would win in a war between Mars and Earth. And that’s a weird thing to think about, but given a bunch of beliefs that I have—I think SpaceX can probably get to Mars in a decade or two, I think AI will be able to autonomously invent a bunch of new technologies that allow you to set up a space colony, I think a lot of the sociopolitical dynamics of this can be complicated… Maybe this isn’t the thing we should be thinking about, but I want a reason why it’s not the type of thing we should be thinking about.

Maybe that’s a little too far. The more grounded version of this is: what if corporations end up with power analogous to governments, and the real conflicts are on that level. There's this concept of the network state, this distributed set of actors bound together with a common ideology. What if the conflicts that arise as AI gets developed look more like that than conflicts between traditional nation-states? This all sounds kind of weird and yet when I sit down and think “what are my beliefs about the future of technology? How does this interface with my sociopolitical and geopolitical beliefs?” weird stuff starts to fall out.

Lastly, synthesizing different moral frameworks. Right back at the beginning of the talk, I was like, look. We have these three waves. And we have consequentialism, we have deontology, and we have virtue ethics, as these skills that we want to develop as we pass through these three waves. A lot of this comes back to Derek Parfit. He was one of the founders of EA in a sense, and his big project was to synthesize morality—to say that all of these different moral theories are climbing the same mountain from different directions.

I think we’ve gotten to the point where I can kind of see that all of these things come together. If you do consequentialism, but you’re also shaping the world in these large-scale political ways, then the thing you need to do is to be virtuous. That’s the only thing that leads to good consequences. All of these frameworks share some conception of goodness, of means-end reasoning.

There’s something in the EA community around this that I’m a little worried about. I’ve got this post on how to have more cooperative AI safety strategies, which kind of gets into this. But I think a lot of it comes down to just having a rich conception of what it means to do good in this world. Can we not just “do good” in the sense of finding a target and running as hard as we can toward it, but instead think about ourselves as being on a team in some sense with the rest of humanity—who will be increasingly grappling with a lot of the issues I’ve laid out here?

What is the role of our community in helping the rest of humanity to grapple with this? I almost think of us as first responders. First responders are really important — but also, if they try to do the whole job themselves, they’re gonna totally mess it up. And I do feel the moral weight of a lot of the examples I laid out earlier—of what it looks like to really mess this up. There’s a lot of potential here. The ideas in this community—the ability to mobilize talent, the ability to get to the heart of things—it’s incredible. I love it. And I have this sense—not of obligation, exactly—but just…yeah, this is serious stuff. I think we can do it. I want us to take that seriously. I want us to make the future go much better. So I’m really excited about that. Thank you.

Thanks for this very thoughtful reply!

I have a lot to say about this, much of which boils down to a two points:

The rest of your comment I agree with.

I realize that point (1) may seem like nitpicking, and that I am also emotionally invested in it for various reasons. But this is all in the spirit of something like avoiding reasoning from fictional evidence: if we want to have a good discussion of avoiding unnecessary polarization, we should reason from clear examples of it. If Jeremy is not a good example of it, we should not use him as a stand-in.

Right, this is in large part where our disagreement is: whether Jeremy is good evidence for or an example of unnecessary polarization. I just simply don’t think that Jeremy is a good example of where there has been unnecessary (more on this below) polarization because I think that he, explicitly and somewhat understanably, just finds the idea of approval regulation for frontier AI abhorrent. So to use Jeremy as evidence or example of unnecessary polarization, we have to ask what he was reacting to, and whether something unnecessary was done to polarize him against us.

Dislightenment “started out as a red team review” of FAIR, and FAIR is the most commonly referenced policy proposal in the piece, so I think that Jeremy’s reaction in Dislightenment is best understood as, primarily, a reaction to FAIR. (More generally, I don’t know what else he would have been reacting to, because in my mind FAIR was fairly catalytic in this whole debate, though it’s possible I’m overestimating its importance. And in any case I wasn’t on Twitter at the time so may lack important context that he’s importing into the conversation.) In which case, in order to support your general claim about unnecessary polarization, we would need to ask whether FAIR did unnecessary things polarize him.

Which brings us to the question of what exactly unnecessary polarization means. My sense is that avoiding unnecessary polarization would, in practice, mean that policy researchers write and speak extremely defensively to avoid making any unnecessary enemies. This would entail falsifying not just their own personal beliefs about optimal policy, but also, crucially, falsifying their prediction about what optimal policy is from the set of preferences that the public already holds. It would lead to writing positive proposals shot through with diligent and pervasive reputation management, leading to a lot of unnecessary and confusing hedges and disjunctive asides. I think pieces like that can be good, but it would be very bad if every piece was like that.

Instead, I think it is reasonable and preferable for discourse to unfold like this: Policy researchers write politely about the things that they think are true, explain their reasoning, acknowledge limitations and uncertainties, and invite further discussion. People like Jeremy then enter the conversation, bringing a useful different perspective, which is exactly what happened here. And then we can update policy proposals over time, to give more or less weight to different considerations in light of new arguments, political evidence (what do people think is riskier: too much centralization or too much decentralization?) and technical evidence. And then maybe eventually there is enough consensus to overcome the vetocratic inertia of our political system and make new policy. Or maybe a consensus is reached that this is not necessary. Or maybe no consensus is ever reached, in which case the default is nothing happens.

Contrast this with what I think the “reduce unnecessary polarization” approach would tend to recommend, which is something closer to starting the conversation with an attempt at a compromise position. It is sometimes useful to do this. But I think that, in terms of actual truth discovery, laying out the full case for one’s own perspective is productive and necessary. Without full-throated policy proposals, policy will tend too much either towards an unprincipled centrism (wherein all perspectives are seen as equally valid and therefore worthy of compromise) or towards the perspectives of those who defect from the “start at compromise” policy. When the stakes are really high, this seems bad.

To be clear, I don’t think you’re advocating for this "compromise-only" position. But in the case of Jeremy and Dislightenment specifically, I think this is what it would have taken to avoid polarization (and I doubt even that would have worked): writing FAIR with a much mushier, “who’s to say?” perspective.

In retrospect, I think it’s perfectly reasonable to think that we should have talked about centralization concerns more in FAIR. In fact, I endorse that proposition. And of course it was in some sense unnecessary to write it with the exact discussion of centralization that we did. But I nevertheless do not think that we can be said to have caused Jeremy to unnecessarily polarize against us, because I think him polarizing against us on the basis of FAIR is in fact not reasonable.

I disagree with this as a textual matter. Here are some excerpts from Dislightenment (emphases added):

He fairly consistently paints FAIR (or licensing more generally, which is a core part of FAIR) as the main policy he is responding to.

It is definitely fair for him to think that we should have talked about decentralization more! But I don’t think it’s reasonable for him to polarize against us on that basis. That seems like the crux of the issue.

Jeremy’s reaction is most sympathetic if you model the FAIR authors specifically or the TAI governance community more broadly as a group of people totally unsympathetic to distribution of power concerns. The problem is that that is not true. My first main publication in this space was on the risk of excessively centralized power from AGI; another lead FAIR coauthor was on that paper too. Other coauthors have also written about this issue: e.g., 1; 2; 3 at 46–48; 4; 5; 6. It’s a very central worry in the field, dating back to the first research agenda. So I really don’t think polarization against us on the grounds that we have failed to give centralization concerns a fair shake is reasonable.

I think the actual explanation is that Jeremy and the group of which he is representative have a very strong prior in favor of open-sourcing things, and find it morally outrageous to propose restrictions thereon. While I think a prior in favor of OS is reasonable (and indeed correct), I do not think it reasonable for them to polarize against people who think there should be exceptions to the right to OS things. I think that it generally stems from an improper attachment to a specific method of distributing power without really thinking through the limits of that justification, or acknowledging that there even could be such limits.

You can see this dynamic at work very explicitly with Jeremy. In the seminar you mention, we tried to push Jeremy on whether, if a certain AI system turns out to be more like an atom bomb and less like voting, he would still think it's good to open-source it. His response was that AI is not like an atomic bomb.

Again, a perfectly fine proposition to hold on its own. But it completely fails to either: (a) consider what the right policy would be if he is wrong, (b) acknowledge that there is substantial uncertainty or disagreement about whether any given AI system will be more bomb-like or voting-like.

I agree! But I guess I’m not sure where the room for Jeremy’s unnecessary polarization comes in here. Do reasonable people get polarized against reasonable takes? No.

I know you're not necessarily saying that FAIR was an example of unnecessary polarizing discourse. But my claim is either (a) FAIR was in fact unnecessarily polarizing, or (b) Jeremy's reaction is not good evidence of unnecessary polarization, because it was a reaction to FAIR.

I think all of the opinions of his we're discussing are from July 23? Am I missing something?

A perfectly reasonable opinion! But one thing that is not evident from the recording is that Jeremy showed up something like 10-20 minutes into the webinar, and so in fact missed a large portion of our presentation. Again, I think this is more consistent with some story other than unnecessary polarization. I don't think any reasonable panelist would think it appropriate to participate in a panel where they missed the presentation of the other panelists, though maybe he had some good excuse.