After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso is one of the most bracing, insightful, and important books I’ve ever read. I strongly recommend that everyone reading this sentence go and pre-order it immediately. (That’s the first time I’ve ever issued such a universal recommendation, so it isn’t cheap praise.) In my two-part review, I’ll try to convey some of why I think so highly of the book. The game plan:

- Part #1 (today’s post) explores why depopulation is bad. A vital corrective to all those still stuck in the 1970s “population bomb” mindset of thinking that we have “too many people on the planet already” and welcome having fewer people in future.

- Part #2 surveys what doesn’t work—from far-right reproductive illiberalism (which is outright counterproductive), to moderate-left proposals to financially support families (which help a bit, but still don’t suffice)—before turning to the trickier question of what to try next.

The Facts

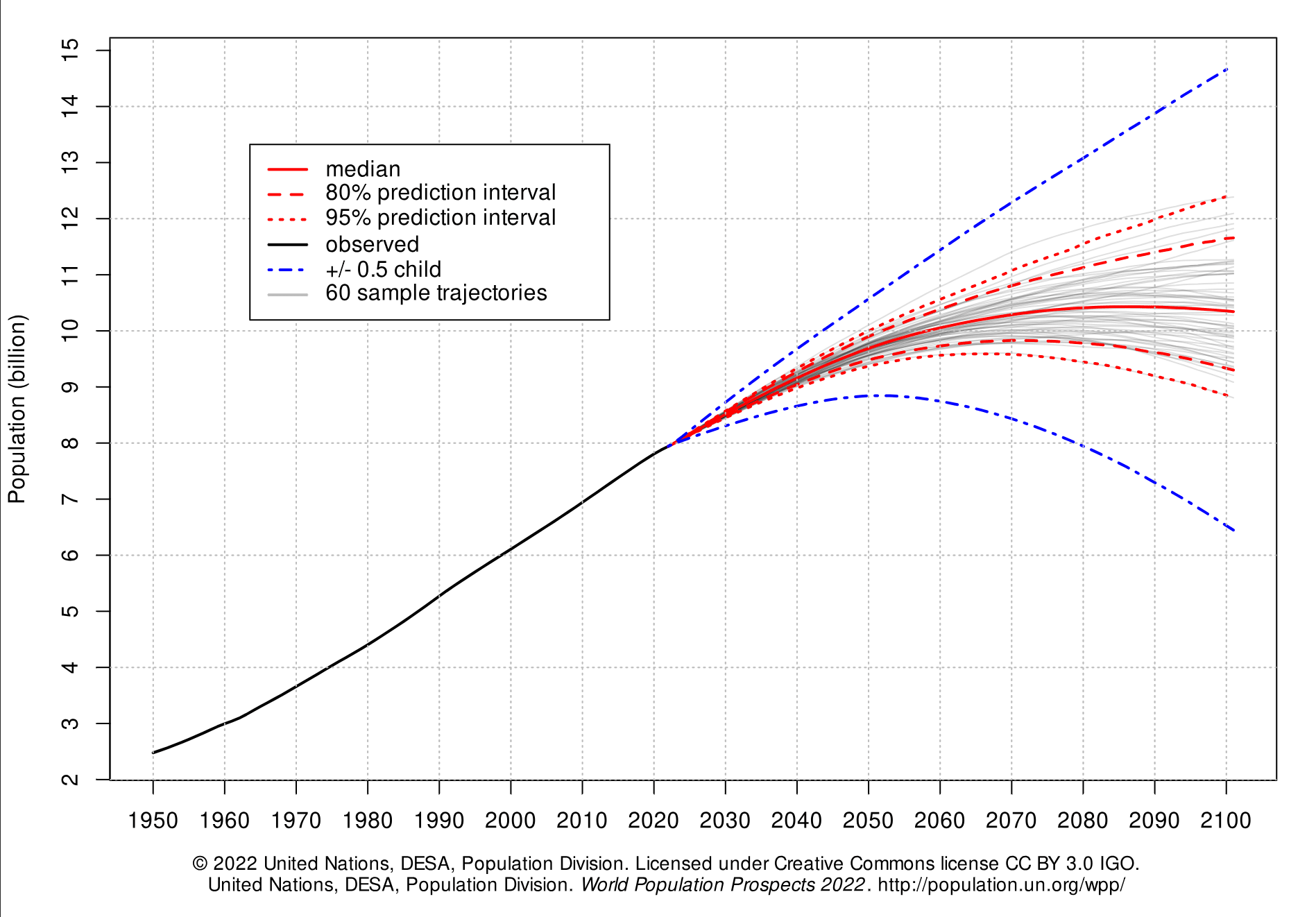

Earth passed “peak baby” in 2012. Now fewer babies are born each year. Demographers expect peak population to be reached in a few decades, followed by a shocking plummet.[1] Below-replacement fertility is perhaps the simplest and most probable extinction risk around:

If humanity stays the course it is on now, then humanity’s story would be mostly written. About four-fifths written, in fact. Why four-fifths? Today, 120 billion births have already happened,[2] counting back to the beginning of humanity as a species, and including the births of the 8 billion people alive today. If we follow the path of the Spike, then fewer than 150 billion births would ever happen. That is because each future generation would become smaller than the last until our numbers get very small.

Something needs to change, and drastically, if humanity is to avoid this fate. (As Spears and Geruso note: “in none of the twenty-six countries where life-long birth rates have fallen below 1.9 has there ever been a return above replacement.”)

Is Population Bad?

I’ve noticed that many—esp. older—academics seem stuck in the mindset of worrying about “overpopulation”, and hence welcome the prospect of depopulation. The crux of the disagreement may come down to a pair of empirical and ethical disputes:

- On present margins, do people on average have more positive or negative externalities? (Empirical question about causal-instrumental effects)

- Do human lives, on average, have intrinsic value? (Ethical question)

The bulk of the book is dedicated to answering the empirical question, and allaying the concerns that lead too many to curse humanity and wish for fewer of us. I won’t be able to do their comprehensive discussion justice here, but just to flag a few highlights:

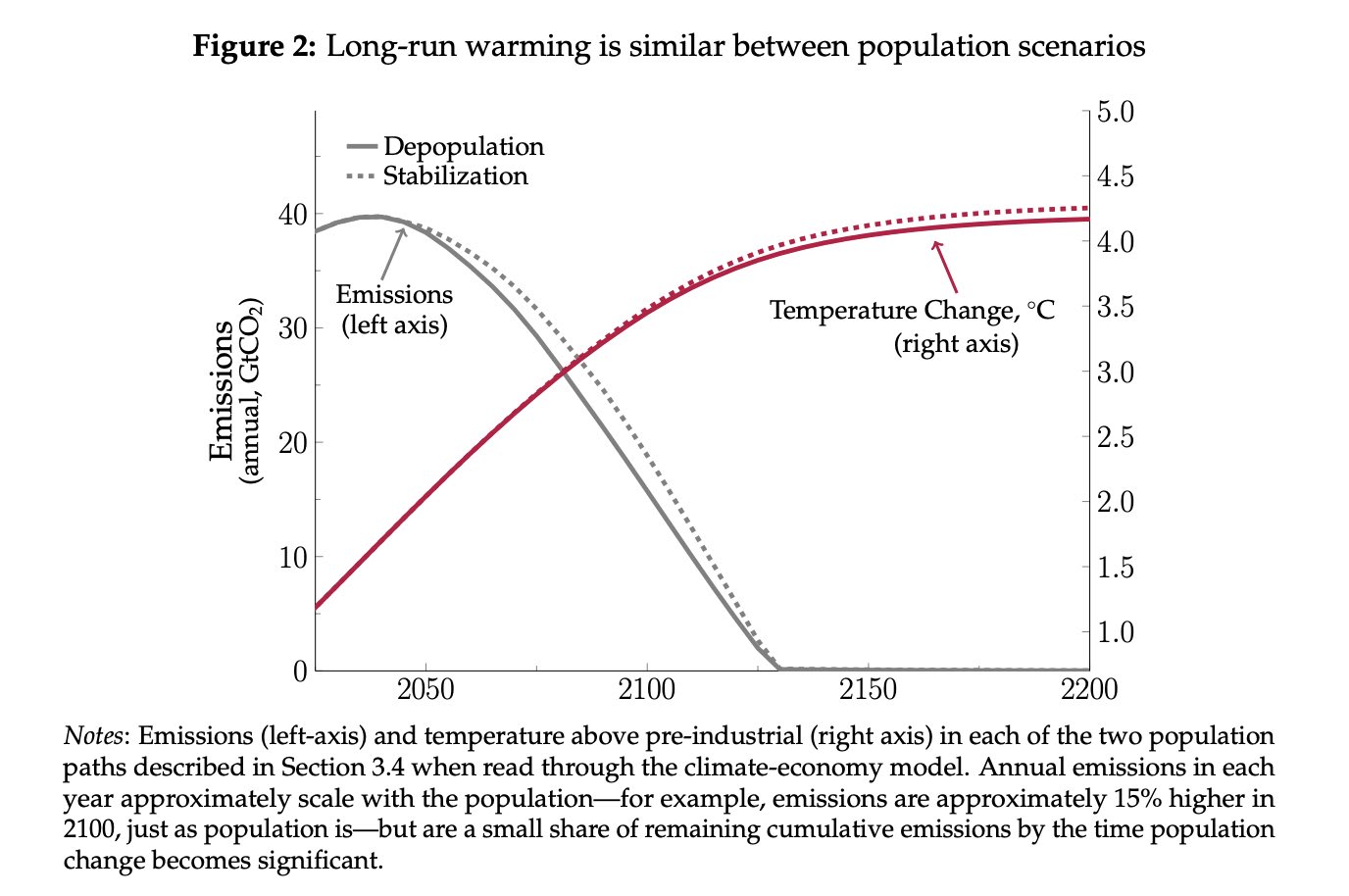

Climate change

The most commonly-expressed concern is, of course, climate change. And here, Spears and Geruso have an absolutely decisive response: timing is everything, and depopulation is too slow to help. We need to decarbonize over the coming couple of decades. Depopulation after 2080 (or whatever) won’t help with that. If anything, it may just make things worse (as society shifts more and more of its limited resources towards sustaining its disproportionately elderly populations, leaving less for investments in green research and infrastructural deployment to actually solve the problems that past generations created). As Spears & Geruso put it:

The only way to confront climate change is to reach net-zero emissions—and soon. If we do that, we will have averted the worst disaster. And if we do that, then an additional person, or an additional billion, born afterward doesn’t matter for emissions. At all. Zero times 9 billion is the same number as zero times 8 billion. Climate progress may turn better or worse in the coming decades. But that will be determined by technology, social awareness, and policy, not by population size.

Perhaps the biggest mental shift needed here is to stop thinking of passivity as the solution (“if only there were fewer people consuming energy!”), and instead recognize that we need active solutions—green innovation and deployment—so that future generations are helping rather than harming the environment. Reducing birth rates now doesn’t reduce emissions in the next 25 years, but it does mean fewer scientists developing breakthroughs in 2050, and less economic capacity to implement new solutions at that time.

Progress comes from people

Chapter 6, “Progress comes from people”, may be my favorite. It explains the following key insights from the science and economics of innovation (why we should have a fundamentally “positive-sum” rather than “zero-sum” view of other people):

Populous is prosperous. A more populous future would raise living standards. Mainly this is because people contribute to the ideas, creativity, experimentation, and technology that benefit others.

They illustrate this with the example of “Kangaroo Mother Care” (KMC) saving the lives of low-birthweight babies in India today, after being invented in Colombia in 1978 and then tweaked and refined by many in the years since.

Spears & Geruso add: “Somehow we’ve made everything more abundant as the population has soared. Is that history a fluke?… It’s time to understand the how and why so we can see what we might lose as humanity’s numbers recede.”

A prize-winning idea: More of us generate more ideas. And that can mean better lives for each of us.

A fact about facts: Facts don’t get used up, but they might go undiscovered.

Strength is in our numbers, not just our rare luminaries. Non-rival innovation is so powerful that even without outliers—even in an alternative universe in which everyone was equally (unexceptionally) intelligent, adventurous, creative, kind, and organized—progress would depend on population size.

Plus a key idea from chapter 7:

How not to get a slice of pie. Having fewer people around would mean there were fewer people who want exactly what you want. And that might be a problem for you getting what you want. Your neighbors are not eating your pie slice. They’re the reason someone is baking.

They conclude:

Whatever it is you value that humans make and do, was there less of it a century ago, when there were fewer of us on the planet together? Vaccines? Streaming, high-budget television? Books or newsletters by a writer who is just your style? Social statistics and ideas about how to use them to build better communities? If so, the Spike warns you not to be confident that a few hundred million people will pull it off in a small and shrinking future. Nobody knows what a complex, interdependent modern economy would be able to produce when there are so few people to fill its niches. The appearance of niche economic specialization in human society is so new, on the scale of the Spike, that nobody should pretend to know what would happen without it.

(Maybe AI could fill the void, but we surely don’t want to gamble the future of civilization on that.)

More Good is Better

Chapter 8 turns to a moral principle that's dear to my heart:

More Good is Better. It’s better if there is more good in the world, other things being equal, and worse if there is less. That includes good lives: It’s better if there are more good lives.

Like beneficentrism, I don’t think this should be at all controversial. Whatever deontic constraints, prerogatives, and partialities you’re inclined to accept, you should also accept that More Good is Better (all else equal).

Spears & Geruso offer a powerful thought experiment to those who claim that there was no “shortage” of people when global population was just half what it is now: Imagine that half the people you know and love never existed. You wouldn’t miss them in particular; you wouldn’t know what you’re missing. But still, comparing our world to that imagined half-world, we are surely right to be glad that those extra good lives exist. (You would seem not to fully cherish them if you didn’t feel this way, and didn’t regard the preference as one that is warranted by the intrinsic value of your loved ones. Really, anyone who fully knew them ought to wish them well and be glad that they exist.)

Now generalize. Just like it isn’t only bad when you or your loved ones suffer (others’ suffering matters too), so it isn’t only good when you or your loved ones exist (others’ existence matters too). There is no good reason to deny this.[3]

Related Reading

While you wait for the book’s July 8 release date, I recommend also checking out:

- Victor Kumar on The Vanishing of Youth

- Alice Evans and Ross Douthat on the collapse of coupling as a possible (partial) explanation of fertility decline. (Go fall in love, people!)

- Noah Smith on ‘The dawn of the posthuman age’—on the trends of fewer families and ever-increasing time spent online.

Framing the Debate

Just a reminder that I particular welcome debate around the two key questions:

- Do people, on average, have positive or negative externalities (instrumental value)?

- Do people's lives, on average, have positive intrinsic value (of a sort that warrants promotion, all else equal)?

Two common pitfalls of low-quality public debate on this topic that I'd rather avoid:

- As per footnote 3, please don't conflate pro-natalism with procreative duties or opposition to reproductive freedom. (If you want to raise concerns in that vein, make sure you first read my post on the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy.) Part 2 of my review will share more from the book on why coercion is not the solution.

- Please don't conflate concern about global population decline with far-right obsessions about race, "great replacement", etc. I'm all for more immigration (I'm an immigrant myself), but moving people around does not address global depopulation. Its virtues lie elsewhere (increasing freedom and labor productivity, reducing poverty, etc.).

- ^

The precise gradients will vary depending on whether global average fertility rates are closer to 1.8 or 1.2, but the general shape of the exponential curve is surprisingly similar either way.

- ^

Though I’m skeptical that “# of births” is the right metric for partitioning the human story. Since infant mortality used to be vastly higher (and life expectancy in general much lower), we presumably have a higher proportion of life-years still to go than this passage might suggest. So the remaining births to come might yet contribute a disproportionately large amount to humanity’s story. It’s complicated :-)

- ^

Some bad reasoners, frightened by the false specter of procreative duties, commit the “No Duty → No Good” fallacy. So I was happy to see Dean & Mike run with my suggested kidney donation analogy to push back against this!

70%➔ 80% disagreeI remain unconviced by the arguments in the book (based on this post). My main disagreement is that it assumes that the main downside of a larger population is climate change (which I don't think it is), and then goes on to focus exclusively on all the great things we could have with more people. Perhaps not surprisingly, I think this debate is not complete without bringing up the problem of extreme suffering:

The above begs the question. Sure, more good is better, but the book title is not "the case for happy people." Doubling the population would mean:

Maybe one could argue that growing the population would also help us fix all of the above faster, but I seriously doubt it (and it would seem to me more like an instance of suspicious convergence).

The book authors seem to be basically saying "wouldn't it be awesome to have more people like us? Healthy, wealthy, happy-go-lucky, living in a free democracy, and with such high IQ that we might invent a new vaccine?" (Sorry, this might be unfair, but that's at least the vibe I get from this post.) But I think we absolutely need to think about those living in agony too. Until then, I'm unconvinced.

Maybe less importantly (because it may be rather a matter of aesthetics), I'm also not moved much by the argument "aren't you glad to have more books, magazines, high-speed streaming, etc., and wouldn't it be great to have more of that?" There's something hungry ghost-y about it that goes against my striving to be content with less. Like, yes, I admit I really like vaccines, but maybe our goal should be "let's shift our societal priorities such that fewer people go on to become TV producers and instead become vaccine researchers."

Something similar applies to this:

I think the thought experiment is trying to evoke a feeling of sadness at the thought of never having met half the people in your life, but to me it also implies that, right now, I should be sad that I don't have twice the friends I have. I reject this implication.

Anyway, I still appreciate the book summary and will be thinking about the topic more as a result. And I'm still open to changing my mind if there are other arguments related to the problem of extreme suffering.