Introduction

In 2009, Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo published Dead Aid, a scathing critique of Western development efforts in Africa. She argued that decades of well-meaning aid had failed not only to lift African countries out of poverty, but had actively undermined their institutions, encouraged corruption, and created a culture of dependence. Aid, she concluded, was not saving Africa, it was holding it back.

Moyo was not the first to make such claims, and she wouldn't be the last. From economists (like William Easterly’s The White Man’s Burden) to anthropologists (like Jason Hickel’s The Divide) a growing body of literature has criticized how foreign assistance, however generous in appearance, can replicate the very hierarchies and dependencies that colonialism once enforced through direct rule.

Today, a new form of philanthropy has emerged: Effective Altruism. EA, as it’s known, is a movement built around the idea that we should use reason and evidence to do the most good. Often this means funding highly cost-effective interventions like malaria prevention, deworming, or vaccination incentives in the world’s poorest countries, most often in sub-Saharan Africa. EA does not appeal to sentiment, loyalty, or proximity. Instead it seeks measurable impact, like how many lives the intervention saves per dollar, or how many “Quality Adjusted Life Years” it generates.

At first glance, this seems like a clear improvement over the failed aid of the past. But a new wave of critics, often informed by postcolonial theory, have begun to ask whether even these forms of giving can reproduce the same problems they aim to avoid. Could Effective Altruism be neocolonial?

What Is Neocolonialism?

Colonialism, as defined by political philosophers, is the reduction of one people’s sovereignty by another, typically through direct political and military domination.

Neocolonialism, by contrast, operates after formal independence. It sustains the same power dynamics through economic control, international institutions, and cultural influence.

As philosopher Oseni Taiwo Afisi writes, neocolonialism refers to “the actions and effects of certain remnant features and agents of the colonial era in a given society.” It’s colonialism without conquest.

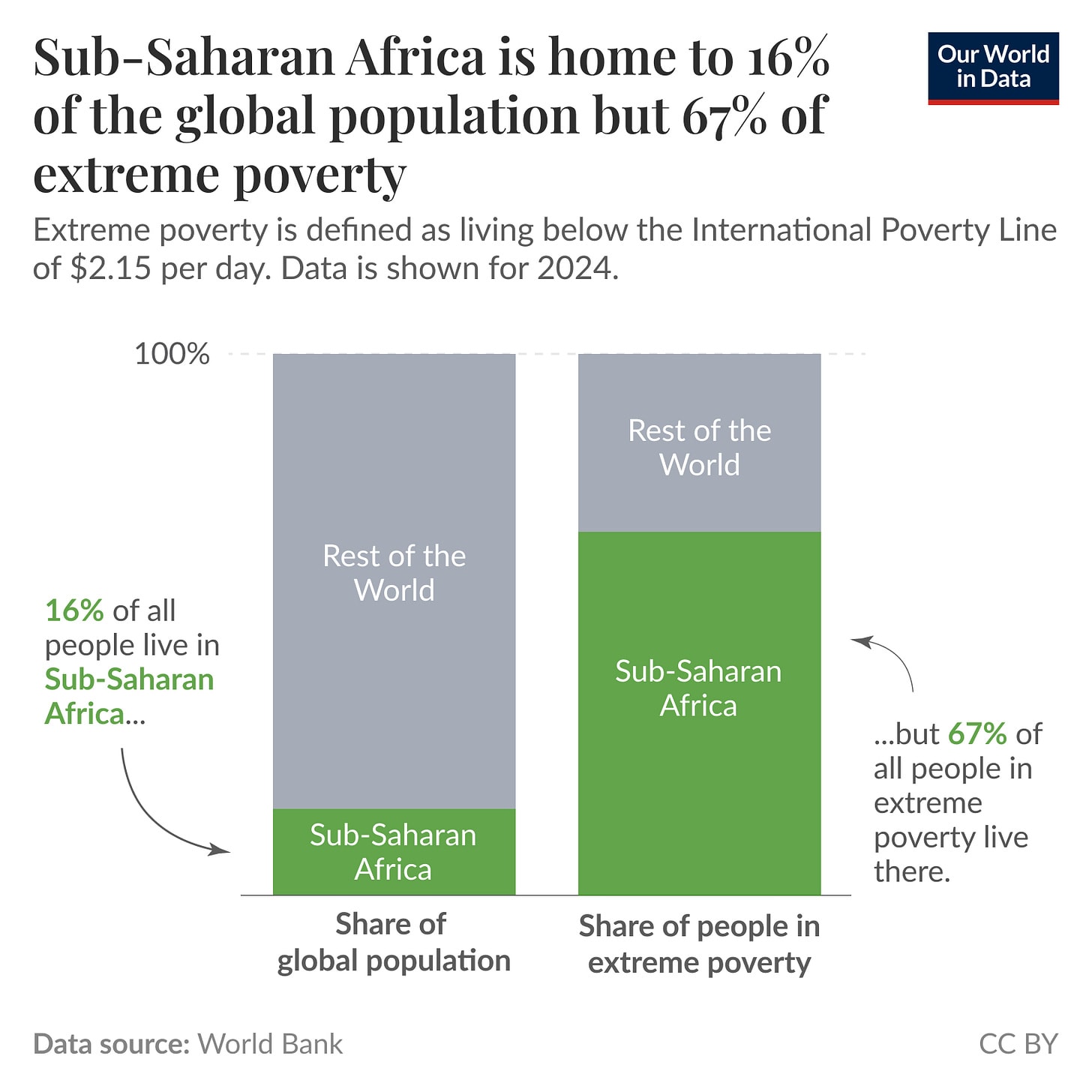

This framing matters. Sub-Saharan Africa, the region where EA often focuses its efforts, continues to bear the scars of colonialism. According to the World Bank:

These numbers are not an accident. They reflect what economists Acemoglu and Robinson call “dysfunctional institutions” rooted in centuries of slavery, conquest, and extractive rule. Philanthropy has long played a role in managing these inequalities. It was often used to soften or sanitize imperial policy, providing humanitarian cover for strategic control. Could EA be doing the same?

I will split the neocolonial critique into three parts[1]: EA could replicate colonial power…

- By keeping poor people poor (e.g. addressing symptoms rather than causes)

- By making them dependent (e.g. undermining and displacing local institutions)

- By not listening to them (e.g. excluding the voices of those it aims to help)

In this post I will give an overview of the arguments and counterarguments people have given for these three critiques.

1. Does Effective Altruism Keep Poor People Poor?

Critics argue that EA treats extreme poverty as a technical issue: something to be managed with bed nets, deworming pills, or vaccines, but without addressing the deeper political and economic systems that cause it in the first place. The result, they say, is a form of charity that may alleviate suffering, but risks reinforcing global inequality and disempowerment.

This concern hinges on a key ethical idea: that charity should be a temporary bridge toward self-sufficiency. But effective altruism, critics argue, sometimes treats it as a permanent solution.

One of the more forceful critiques comes from an aid worker writing under the pseudonym Carneades, who argues that EA charities “take jobs away from communities,” “do not allow for communities to decide what they need,” and “do the work for a community, instead of building capacity and increasing autonomy.” This model, they warn, is great for the charity since it “ensures that the community will need aid forever.”

The political theorist Cecelia Lynch sees similar dangers, warning that EA “does not counter the neocolonial and paternalistic practices of the aid industry” and may even “reinscribe them more forcefully.” In her view, new philanthropy in general —and EA in particular— may appear innovative but often repeats old power dynamics in more technocratic language.

We saw how development economists like Dambisa Moyo and William Easterly share this concern about the modern aid sector. But perhaps it’s put most bluntly by Nobel prize winning economist Angus Deaton in The Great Escape:

Development is neither a financial nor a technical problem but a political problem, and the aid industry often makes the politics worse.

This is the core of the critique: poverty isn’t just about lacking resources — it’s about lacking control. And if interventions don’t help restore that control, they risk being palliative rather than transformative.

From this perspective, EA’s most celebrated charities may save lives without empowering communities. Critics argue that this turns poverty into a permanent management problem, rather than a structural injustice to be dismantled.

Counterarguments

Anthropologist China Scherz complicates this picture. Based on fieldwork with Ugandan nonprofits, she found that many aid recipients actually prefer programs that give them tangible things —food, medicine, money— over less direct “capacity-building” efforts. This might support EA’s focus on cost-effective interventions, although it might also be that the recipients think “capacity-building” charities could be better, but that good ones simply aren’t being created.

More direct counterarguments come from Effective Altruists themselves. Holden Karnofsky (co-founder of GiveWell and Open Philanthropy) and Will MacAskill (co-founder of the Centre for Effective Altruism) respond that the kinds of charities favored by EA are deliberately chosen because they don’t repeat past mistakes. They’re carefully researched, tested for negative side effects, and focused on interventions with clear, measurable benefits — like preventing deaths or increasing school attendance.

EA-philosopher Peter Singer echoes this, but with a more practical focus. He argues that if charity hasn’t worked in the past, it’s mostly because we haven’t done enough of it, not because it’s inherently flawed. Most rich countries still give far below the UN target of 0.7% of GNI, and political motives often override impact. Singer claims that in recent decades, “we [spent] more than three times as much on beauty products as the governments we elect spend on ending extreme poverty.”

Organizations like Giving What We Can agree and go even further. They argue that well-designed aid can actually strengthen institutions and create opportunities for sustainable long-term growth, if deployed with care. Rather than abandoning charity, they say we should reform and scale up the kind that works.

Decolonial critics, by and large, acknowledge that the worst-case view —that EA keeps people poor— is too strong. A more modest but still pressing version of the critique holds that EA currently underestimates the long-term risks of dependency, and does too little to support local political development or economic growth.

2. Does EA Keep Poor People Dependent?

Many critics don’t claim that effective altruism is inherently neocolonial. Rather, they argue that its current practice fails to take seriously enough the risks of keeping poor countries dependent. Even if the interventions are effective on paper, their broader political consequences may be corrosive.

Political scientist Emily Clough, for example, has argued that when an EA-aligned charity provides high-quality public services (like education or healthcare) in a given region, it can cause the state to scale back its own efforts. Rather than serving as a supplement, the NGO becomes a replacement, and people who aren’t reached by the charity lose access to services that might once have been theirs by right.

Philosopher Jeff McMahan, drawing on Clough’s critique, writes that:

“[Foreign aid] may enable dictators to [...] resist pressures to change the practices and institutions that perpetuate extreme poverty.”

When philanthropists work through NGOs, their efforts may conflict with and partly undermine the activities of more legitimate —and potentially more longterm effective— actors, such as local or national governments. In bypassing states, NGOs remove the incentive for those states to improve, weakening long-term accountability and capacity.

Nobel prize winning economist Daron Acemoglu raises a similar concern. Even when EA-funded services are well-intentioned and evidence-based, they may still erode institutional legitimacy:

“When key services we expect from states are taken over by other entities, building trust in the state and developing state capacity in other crucial areas may become harder.”

Philosopher Larry Temkin adds another layer to the critique: outside actors can pull highly qualified locals out of the public sector to work for NGOs, shift national priorities to align with foreign interests, and reduce governments’ responsiveness to their citizens. In his words, these interventions risk “negatively impacting local authority and autonomy.”[2]

In other words, even if EA-style aid helps individuals survive, it might do so in ways that damage the very systems needed to support people sustainably.

This leads to a broader point made by Angus Deaton: the problem is not simply lack of money. It’s politics:

“Development is neither a financial nor a technical problem but a political problem, and the aid industry often makes the politics worse. […]

Lack of money is not killing people. The true villains are the chronically disorganized and underfunded health care systems about which governments care little, along with well-founded distrust of those governments and foreigners, even when their advice is correct.”

If foreign charities become the main providers of essential services, governments may stop investing in their own systems, and citizens may stop expecting them to. In this scenario, what appears as humanitarian relief may end up as a long-term governance failure, one that mimics —and in some cases reinforces— colonial dynamics.[3]

Whether framed as a short-term displacement of public institutions or a long-term erosion of democratic self-governance, the critique is clear: the more people rely on aid from outside actors, the harder it becomes to demand lasting solutions from inside.

Counterarguments

Effective altruists acknowledge that aid can have unintended consequences. But they argue that critics often overlook the positive, long-term effects that even simple interventions can produce, effects that go beyond survival and into the realm of empowerment.

Holden Karnofsky argues that aid shouldn’t just be measured by how many lives it saves, but also by the indirect ripple effects it creates. A child who survives malaria can go to school. A family that receives a cash transfer can invest in a small business. These kinds of material improvements, over time, can create the conditions for political engagement and social transformation. Karnofsky writes:

“A substantial part of the good that one does may be indirect: the people that one helps directly [...] become more empowered to contribute to society, and this in turn may empower others.”

He even suggests that the long-term political and social gains might outweigh the immediate health or income gains EA charities typically measure.

This view is supported by historical analysis. As sociologists Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello have argued, it is precisely when material insecurity decreases that movements for justice and reform tend to grow stronger. When people are no longer consumed by the daily struggle to survive, they can begin to organize, protest, and build alternatives. In this sense, interventions that reduce suffering might be a prerequisite for grassroots resistance.

Another counterargument is that some EAs have looked at ways to make structural improvements. For example, Hauke Hillebrandt and John Halstead wrote a popular essay on the EA Forum arguing that typical EA interventions do little to promote sustained economic growth, and EAs should look at more systemic interventions instead. The essay was very well received and even won an EA Forum prize. It may be that EA is already in the process of changing, but it just takes a while to set in.

3. Does EA Fail To Listen To Poor People?

The final, and perhaps most foundational critique, is that EA interventions are too often designed from the outside —based on what donors or researchers believe is effective— without meaningful consultation with the people these interventions are supposed to help.

The result, critics say, is not just technocratic or impersonal, but paternalistic: a form of help that is imposed, rather than co-created. If poor people are experts in their own needs, who is in a better position to know what would help them? And if effective altruists genuinely want to improve lives, why not begin by amplifying the voices of those they aim to support?

Philosopher Monique Deveaux highlights the political stakes of this. She warns that some forms of aid can “actively undermine grassroots efforts to bring about transformative social change by diverting resources and short-circuiting community-led development processes.” The problem isn't only that EA misses certain voices, it's that its presence may actually make local organizing harder.

The aid worker “Carneades” adds a sharper critique:

[EA] promotes organizations that [...] focus on projects which apply across communities regardless of need. They do not build projects from the bottom up, they drop things from the top down. This harms developing democracies, and it does not allow for communities to decide what they need. Yes, systematically bottom up work is harder to do, but the effects are worth it.

Political theorist Jennifer Rubenstein offers a similar warning. She argues that while EA works well when the “low-hanging fruit” of health and cash interventions are available, deeper progress —especially when it requires systemic change or global reform— will demand far more collaboration with local activists. She writes:

“The effective altruism movement as Singer describes it does not cultivate the expectations, attitudes, or relationships necessary for this kind of work.”

Her suggestion? EA donors should begin supporting existing movements, especially those based in the global South, that are already fighting for inclusion, equality, and justice. She proposes the creation of a “database of effective social movements” to help donors direct attention toward local organizations with the power to shape change from within.

Geographer Matthew Doran goes even further, arguing that EA does not just fail to listen, it may be structurally incapable of hearing certain perspectives. He writes:

“EA’s interventions are only the most effective options according to the priorities and epistemology of its gatekeepers. They are not necessarily the most effective interventions according to the people who receive them.”

For Doran, the problem isn’t just one of bias, it’s one of “epistemic exclusion”. Many Global South perspectives on what matters, what works, and what counts as valid evidence may be “inadmissible or even un-hearable within EA” because they clash with what he calls “capitalist epistemology”; a framework that values quantifiable impact over political or cultural context.

Perhaps the most personal expression of this critique comes from Anthony Kalulu, a Ugandan farmer and activist. Kalulu argues that effective altruism is even worse than traditional philanthropy in how it excludes the poor. In his experience, even large Western foundations like the Gates Foundation occasionally support small grassroots initiatives, but not EA.

Counterarguments

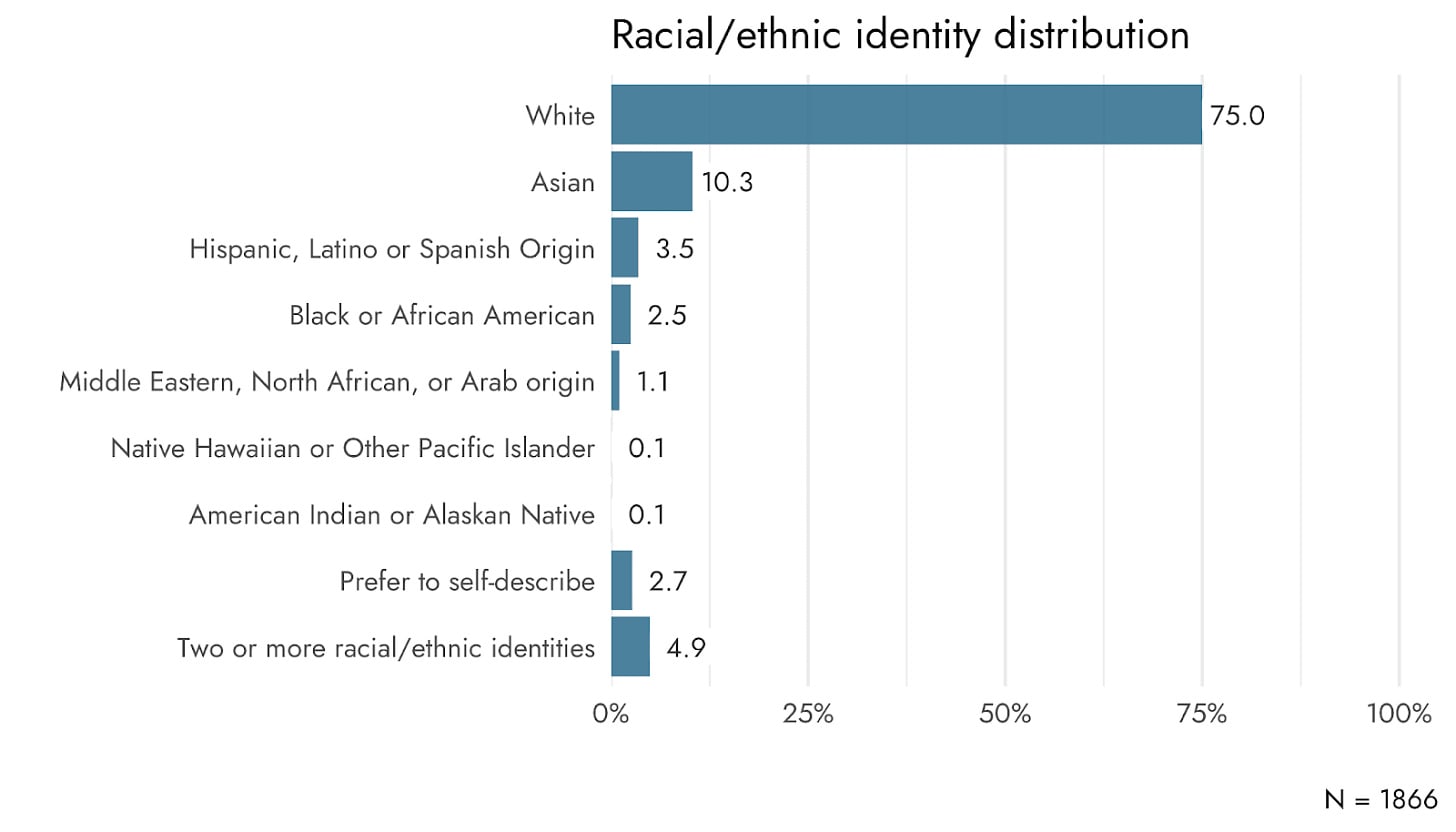

If you look at survey-data of EA demographics, it would be hard to argue that people from the Global South are sufficiently represented:

However, there is one notable EA endorsed charity that does rely on the expertise of poor people. Direct Cash Transfers (DCTs) do what the name implies, they send money directly to people in need, allowing them to spend it however they like, without any strings attached. I’ve previously talked about how similar cash transfers are to reparations, a quintessential decolonial project. So even if this third critique does apply to some, or even most EA interventions, I’d argue DCTs show that it doesn’t apply to all EA interventions.

Conclusion

So, is effective altruism neocolonial?

The first critique (that it keeps people poor) doesn’t really hold. EA interventions do improve lives, and there’s no evidence they’re increasing poverty.

The second (that it makes people dependent) is more complicated. Some interventions risk weakening local institutions, but others may lay the groundwork for autonomy.

The third (that it doesn’t listen) has real force. EA often excludes the voices of those it aims to help, though cash transfers show that it doesn’t have to be an inherent part of the movement.

In short: Effective Altruism may be an improvement over traditional philanthropy of the past, but it’s not yet entirely free of neocolonial dynamics either.

A huge thanks to Maxim Vandaele for helping write this post. All opinions and mistakes are my own.

- ^

Just as a way to structure the post, not to claim that these problems are really separate.

- ^

Philosopher Monique Deveaux echoes these concerns. She critiques EA’s use of Peter Singer’s pond metaphor (where a drowning child must be saved without hesitation) as ethically shallow in the context of development. It ignores what she calls the “most basic risks of adverse unintended effects” including:

- the creation of black markets,

- the disruption of labor markets,

- and the undermining of local institutions.

In other words, even if EA-style aid helps individuals survive, it might do so in ways that damage the very systems needed to support people sustainably.

I feel like the concept of "neocolonialism" is pointing at some important things, but it's also fuzzy and maybe muddling the waters a bit on top of that, since it seems to come with some ideological baggage?

In particular, while I haven't read the texts you're referring to, it gives me the impression that it might be mixing together some things that are morally bad and preventable, like exploitation/greed and not treating certain groups the way we'd want ourselves to be treated, with things that are bad/unfair features of the world that can only be mitigated to a certain degree, because they reflect some of the very things that are bad about poverty and needing help in the first place. (Concretely: The potential for dependencies to develop when help is given -- that's a negative side-effect that we should try to mitigate, but it's to some extent inherent to the dynamics of receiving help and it's not clear it's a priority to mitigate it down to zero, and it certainly shouldn't categorically "taint" the help that was given in an absolute way independent of determining that the negative side-effects do in fact outweigh the positives. Or, on the cited demographics, it makes sense that people with less resources and power will find the idea of becoming an EA less appealing, since part of the appeal of EA, to many EAs, was that their personal resources can do an outsized amount of good or go further overseas. Lastly, there are some things about the nature of tradeoffs around effectiveness that will seem "cold and calculating," but in a way that doesn't let us draw any conclusions about a lack of care.)

So, I liked that you distilled the bad and preventable things that "neocolonialism" might be pointing to into three concrete questions. I find these questions important and think they point to challenging issues (and it would be surprising if anyone did a perfect job across the board).

However, at the end of your post, you go back to the fuzzy thing (EA not yet being free of "neocolonial dynamics"):

Here, I'm not sure to what degree you think this reflects:

(1) serious ("systemic"/"blind spot") failings of EA (perhaps not in the sense of EA being worse than other groups, but let's agree that we do want to hold ourselves to high standards);

(2) things that are good/important to improve, but more on the level of dozens other things that would be good to have as well, so not necessarily the cause of a systemic/blind spot issue;

(3) things that may match some of the connotations of "neocolonialism," but, on reflection, these things don't imply that EAs should do major things differently, because we disagree that the fuzzy concept "neocolonialism" is a well-suited lens for telling us what to do/avoid.

FWIW, in the abstract I think there most likely many things under (2) and perhaps also there could be something under (1), but my point is that it's particularly valuable here to be concrete. Your discussion does mention some things (like supporting grassroots work), but these are of the form "one expert critic said we should do this" and it's not clear how much you think that critic is right, and how much it matters compared to other things we could try to improve.

Thank you for your post! I think it is essential to consider how charity interacts with power dynamics and the risks of neocolonial approaches, but this did make me think of a point in this kind of critique that consistently puzzles me.

You write:

I live in a wealthy country, yet I often appreciate when problems are solved for me without needing my direct involvement. The underlying critique here is valid: local knowledge is invaluable, and listening to those affected will usually improve interventions. As a general heuristic, amplifying local voices makes sense.

However, when I consider how progress works in my own life and in developed countries more broadly, the picture looks different. Many improvements I rely on exist because experts, not locals, prioritized technical knowledge and scale. The water from my tap meets WHO standards rather than being based on local opinion. My appliances result from global competition that identifies expertise wherever it exists. Healthcare is guided not just by local doctors, but also by national and international bodies that assess quality and effectiveness. Medical breakthroughs often arise from global expertise rather than local insight. These examples illustrate that relying solely on local perspectives would leave wealthy countries significantly worse off.

This raises a question: why do we hold global development to a standard of strict localism, when wealthier societies themselves achieved prosperity by leveraging expertise wherever it was found? The principles that drive progress in developed nations, identifying and scaling the best solutions, are directly relevant to tackling global poverty.

Of course, this approach should not override fairness or safety. If interventions risk active harm or require sensitive political trade-offs, local input is crucial. But many EA-funded interventions—like reducing worm infestations, malaria, or lead exposure—are a lot like the water from my tap: technocratic precisely because they avoid contentious political questions. These are large-scale problems that individuals cannot realistically address alone, yet they have minimal local opposition when implemented effectively.

In this sense, I think EA is often more systemic than critics acknowledge. It focuses on solving deep-rooted problems through scalable solutions, much like the systems that underpin prosperity in wealthier countries.

Not sure I even agree with this part. Contrast land use regulation in Japan versus in the United States.

EA global health & development is still largely focused -- in Saunders-Hastings' terminology -- on "low-hanging fruit" like bednets. Its overall spending is somewhere about $1 per person in extreme poverty per year. In my view, those practical realities make me a lot less concerned about these types of criticisms than I might be if the spending were ~ an order of magnitude higher. Most of the proposed mechanisms of harm, like undermining governments, seem rather speculative at low levels of expenditure.

Also, at least the GiveWell top charities target specific causes of under-five child mortality. In general, I'm less concerned about paternalism toward infant beneficiaries than I would be for a program that risked overriding the preferences of adult intended beneficiaries who are capable of making their own choices.

Finally, I think alternatives like funding "local organizations with the power to shape change from within" could risk more significant neo-colonialism, especially if not done very carefully. Investing tens to hundreds of millions a year into fostering social change in the Global South would give EAs a whole lot more directional influence over the lives of the people who live there than distributing bednets. Not only would we be picking which types of change agents got funded in the first place, the preferences and values of an organization's funding source can have a powerful influence on the organization(s) in question. I think that would be a very hard problem to fix, especially because assessing effectiveness (and eligibility for continued funding) in this context would be much more subjective and value-laden than in the anti-malarial context.

I think these sorts of critiques don’t just apply to EA - it seems to me like just about any intervention would fall into one of them.

AMF-style interventions that focus on specific problems, like malaria nets? As you discuss, these avoid problems 1 and 2 (because they’re doing a specific thing that wasn’t already being done, so they’re not taking away local jobs or displacing local capacity) but are vulnerable to problem 3 (because the specific thing they’re doing may not be what the locals want)

Maybe organizations could avoid problem 3 by setting up a system to get public input on their projects so they can avoid doing projects that locals don’t want? But expand this out, and at that point you’re basically running (part of) a government - after all, aggregating people’s preferences into decisions is essentially what governments do. (After all, “locals” aren’t a homogeneous group with uniform preferences.) And then you definitely run into all the usual problems with preference aggregation, and you certainly are trying to replace (part of) the local government’s role.

Maybe avoid that by working with the local government or local institutions, rather than setting up your own preference aggregation method? Well, if the problem is that the local government and local institutions are bad or corrupt, that’s certainly not a good idea.

Or maybe your intervention could be targeted directly at improving the institutions? In that case you certainly are saying that you know how to run institutions better than the locals, which goes back into the “we know better than you” dynamic. And I thought part of the problem with colonialism was replacing local institutions that were illegible but functional with institutions that looked better to the colonizers, but didn’t actually work well for locals.

Should you hire locals to work for you? Well in that case you’re displacing those locals away from whatever else they would be doing. Don’t hire locals and bring in your own people instead? Then you’re taking away jobs and ignoring local expertise.

It seems like if you wanted an intervention that avoided all of these kinds of potential problems, it would have to have the following properties:

But also:

And I’m having a hard time thinking of any intervention that would fit this bill; if the first two things were true, it seems that would imply that locals would do it or ask their governments to do it.

(Even GiveDirectly-style cash transfers could be argued to have the problem: one could argue that local governments should be giving their citizens cash, so that Acemoglu’s critique about “key services of the state being taken over by other entities” would apply here.)

Two other points of this style of critique that I’m confused about are:

"Preference aggregation" is also what civil society (e.g. associations, free newspapers, labor unions, environmental groups) does. Unless Acemoglu has abandoned social liberalism while I haven't looked, I am fairly confident he wouldn't consider all civil society to be "trying to replace (part of) the local government's role". So funding civil society is potentially another broad class of interventions that would fit all those desiderata (like @huw's, it falls under the broader category of "building local capacity").

So for your criteria:

A broad class of interventions that fit this bill are entrepreneurial interventions. The goal would be to build local capacity temporarily in order to prove out the intervention in the eyes of the government (who will want to see local demand and effectiveness), and then hand it over to them. These can be locally informed or have local adaptations (satisfying (1) and (2)), but wouldn’t necessarily be currently done because they’re new ideas.

I think this isn’t true for these kinds of interventions. It’s easy to imagine large gaps between ‘I think this would be a good idea’ and ‘I have the resources, funding, and willingness to do this myself’ or ‘My government will do this’. Governments in particular move slowly and often want proof that an intervention works locally before implementing it themselves.

Do you have an example success story of the kind of intervention that you have in mind?

This was so well-written and now I'm glad to have found your substack! Sometimes, when this debate comes up, I feel that critiques which rely on a different kind of language than that which dominates EA are reworded or ever-so-slightly glazed over. This post takes every perspective it explores, and its language, seriously (which I really appreciate).

Thanks for this. It's great to create maps like this of critiques and responses. I've not heard of several of these people and arguments before.

One point I have raised earlier: If one is worried about neocolonialism, reducing the risk from powerful technology might look like a better option. It is clear that the global south is bearing a disproportionate burden from fossil fuel burning by rich nations. Similarly, misuse or accidents in nuclear, biotechnology and/or AI might also cause damage to people who had little say in how these technologies were being rolled out. Especially preventing nuclear winter seems like something that would disproportionately affect poor people, but I think AI Safety and Biosecurity are likely candidates for lowering the risk of perpetuating colonial dynamics as well.

Regarding argument 3, wanted to note that GiveWell funded a large survey in 2019 to learn about the preferences of its beneficiaries (general commentary, dedicated page, blog post). The learnings from that study changed GiveWell's moral weights, and they've funded more work on understanding beneficiary preferences since then.

There are many more cases of GiveWell considering local insights, cross-context applicability of programming, etc. I'm commenting quickly so not going to pull examples at the moment, but I think it's pretty easy to look at ~any grant writeup and see evidence of this.

I'm focusing on GiveWell in this comment because I think GiveWell is implicitly the target of many critiques of "EA" global health and development funding. I'd retract the comment if it became clear that such critiques weren't referring to GiveWell.

And, this comment isn't intended to address the question of whether GiveWell and other EA-ish funders should do more to listen to beneficiaries and learn from local experts (personal opinion: they should), but I think some of the quoted critiques in argument 3 above are false if taken literally. Such critiques are consistently confusing to me; I'm not sure whether to interpret them as bad faith, imprecise, or as operating from very different basic views on moral philosophy and ethical obligation.

(commenting in personal capacity)

I agree that "people in EA" are not representative of the people that EA is working to help. But I don't think it follows that "EA doesn't listen" and I would actually argue that EA charities are systematically listening to beneficiaries in ways that are actually quite deviant and unusual in foreign aid.

GiveDirectly is arguably the most extreme example of this, moving money directly to beneficiaries to spend as they like. What could be less "designed from the outside" than that? But there are also other cases as well. For example, in 2019 GiveWell commissioned a survey of beneficiaries to ask about how they would trade off different possible program outcomes.

Finally, most GHD EA charities (including AMF, GiveDirectly, and others), and indeed by my understanding most foreign NGOs, operate their programs in consultation with local authorities.

The claim that EA charities "focus on projects which apply across communities regardless of need" seems to be making a normative claim about what is needed. Did the person making this claim consult the local communities beforehand? I would be curious to hear an example of a community where an EA GHD charity is executing unneeded or even unwanted projects. Some villages have said "no" to GiveDirectly, and GD is perfectly happy to respect that choice.

Just on the second point—I do think it would be consistent with EA values and broadly good for EAs to normatively value government partnerships more highly. Mulago also talk a lot about finding a ‘doer at scale’, and are very excited about government in this regard.

I wonder if there are ways of evaluating the economic impact of strengthening local institutions vs trying to implement alone.

(Obviously, in many contexts, this is easier said than done—but I also see lots of EA charities operate in countries with capable governments that don’t consider government as the default long-term doer.)

Could you give an example?

Executive summary: This exploratory overview by Bob Jacobs surveys arguments for and against the idea that Effective Altruism (EA) may perpetuate neocolonial dynamics, ultimately concluding that while EA improves lives and avoids some past aid failures, it remains vulnerable to critiques about dependency and exclusion—particularly its limited engagement with the perspectives and agency of aid recipients.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

When thinking about the 'neocolonialist criticism', I think it's worth taking some time to critically evaluate the ideological power structures that lead to people talking about 'neocolonialism'.

Because what I think is quite clear 'neocolonialism' doesn't really make sense from a truth-seeking perspective. To run very quickly through the post, we start with a definition of 'colonialism' which should raise some red flags:

What I think immediately jumps out here is... the absence of any mention of colonists? According to this definition, Icelandic colonization of Greenland was... not colonialism. But the Allied invasion of Germany in 1945 was colonialism?

But then it gets worse. We two different, incredibly vague definitions, neither of which are equivalent to each other:

I'm not going to spend a lot of time on these definitions, except to note they also don't really make sense - are Roman roads and Catholic churches in England, a remnant feature of Roman Imperialism, neocolonialism?

We then jump to an allegation that poverty in Africa is due to colonialism (and, perhaps, also neocolonialism):

But the chart attached doesn't show this at all. It shows there is a higher fraction of people in poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa than elsewhere. But there is no reason to think this is because of colonialism - after all, throughout history people all over the world have been repeatedly had their sovereignty reduced through military and political domination, it's not unique to sub-Saharan Africa. Even if you for some reason ignored all non-European colonialism, Sub-Saharan Africa was actually colonized for a much shorter period of time than many other parts of the world because of Malaria - Canada is rich and Ethiopia is poor, but Canada is a deeply colonial country in a way that Ethiopia is not.

So why do people like to use such a vague and misleading concept? I think the answer is it serves a very convenient ideological purpose.

In the aftermath of the second world war, a lot of people wanted to claim that the reason Africa was poor compared to other parts of the world was because of imperialism. Unfortunately, their predictions that Africa would rapidly develop once granted their independence were falsified, and most of the standard explanations for this were not congruent with nationalist or leftist ideology. As such, neocolonialism becomes a very convenient god-of-the-gaps - it allows them to explain why Africa is poor because Europeans are extracting resources and directly administering territory and why Africa is poor because Europeans are giving foreign aid after giving independence.

Importantly, no measure of degree is required for allegations of neocolonialism. Any sensible accounting would show that the degree of European control over sub-Saharan Africa has fallen dramatically post independence, and the continuing interactions (e.g. as export markets, or as providers of advanced technologies and foreign aid) have little in common with the behaviours that motivated opposition to colonialism in the first place.

What does this mean from an EA perspective? Arguments about whether EA should 'listen to poor people' more are a sensible thing to discuss. But framing this in terms of as fundamentally flawed a concept as 'neocolonialism' casts more shadow than light over the issue.