[TL;DR: I didn't find much of value in the book. The quality of argumentation is worse than on most blogs I read. Maybe others will have better luck discerning any hidden gems in the mix?]

The Good It Promises, the Harm It Does: Critical Essays on Effective Altruism (eds. Adams, Crary, & Gruen) puts me in mind of Bastiat’s Candlestick Makers' Petition. For any proposed change—be it the invention of electricity, or even the sun rising—there will be some in a position to complain. This is a book of such complaints. There is much recounting of various “harms” caused by EA (primarily to social justice activists who are no longer as competitive for grant funding). But nowhere in the volume is there any serious attempt to compare these costs against the gains to others—especially the populations supposedly served by charitable work, as opposed to the workers themselves—to determine which is greater. (One gets the impression that cost-benefit analysis is too capitalistic for these authors to even consider.) The word “trade-off” does not appear in this volume.

A second respect in which the book’s title may be misleading is that it is exclusively about the animal welfare wing of EA. (There is a ‘Coda’ that mentions longtermism, but merely to sneer at it. There was no substantive engagement with the ideas.)

I personally didn’t find much of value in the volume, but I’ll start out by flagging what good I can. I’ll then briefly explain why I wasn’t much impressed with the rest—mainly by way of sharing representative quotes, so readers can judge it for themselves.

The Good

The more empirically-oriented chapters raise interesting challenges about animal advocacy strategy. We learn that EA funders have focused on two main strategies to reform or eventually upend animal agriculture: (i) corporate cage-free (and similar) campaigns, and (ii) investment in meat alternatives. Neither involves the sort of “grassroots” activism that the contributors to this volume prefer. So some of the authors discuss potential shortcomings of the above two strategies, and potential benefits of alternatives like (iii) vegan outreach in Black communities, and (iv) animal sanctuaries.

I expect EAs will welcome discussion of the effectiveness of different strategies. That’s what the movement is all about, after all. By far the most constructive article in the volume (chapter 4, ‘Animal Advocacy’s Stockholm Syndrome’) noted that “cage- free campaigns… can be particularly tragic in a global context” where factory-farms are not yet ubiquitous:

The conscientious urban, middle-class Indian consumer cannot see that there is a minor difference between the cage-free egg and the standard factory-farmed egg, and a massive gulf separating both of these from the traditionally produced egg [where birds freely roam their whole lives] for a simple reason: the animal protection groups the consumer is relying upon are pointing to the (factory- farmed) cage-free egg instead of alternatives to industrial farming. (p. 45)

Such evidence of localized ineffectiveness (or counterproductivity) is certainly important to identify & take into account!

There’s a larger issue (not really addressed in this volume) of when it makes sense for a funder to go “all in” on their best bets vs. when they’d do better to “diversify” their philanthropic portfolio. This is something EAs have discussed a bit before (often by making purely theoretical arguments that the “best bet” maximizes expected value), but I’d be excited to see more work on this problem using different methodologies, including taking into account the risk of “model error” or systemic bias in our initial EV estimates. (Maybe such work is already out there, and I just don’t know about it? The closest I can think of is Open Philanthropy’s work on worldview diversification, which I like a lot.)

The Bad

My biggest complaint about the book is that (with the notable exception quoted above) it contains very little by way of evidence or argument. It’s effectively a testimonial of social-justice perspectives, but if you don’t already agree with social-justice activists that they know best, there’s little here to change your mind. As the editors make clear in their introduction, their central beef with EA is that its data-driven approach is:

directly at odds with the aims and practices of numerous liberation movements, many of which are distinguished by their insistence on starting with the voices of the oppressed and taking simultaneously empathetic and critical engagement with these voices to guide the development of strategies for responding to suffering. (p. xxvii)

If it’s not obvious to you that oppressed communities know best how to promote animal welfare, well, you’re just a bad person, I guess.

The editors next lament that EA funders’ willingness to fund “care work” on animal sanctuaries is conditional on the sanctuaries doing further indirect good (e.g. by inspiring visitors to subsequently support other effective animal charities), because the direct benefit is so small in scale compared to other efforts. The editors object:

This is not a way of registering the value of care, empathy, and the pursuit of genuine altruism, however, but rather a way of denying these values and reducing them to mere means to other ends. This instrumentalization of deep values makes crucial aspects of the lives of those who bear them invisible— another grave harm of EA. (pp. xxviii-xxix.)

In other words, Animal Charity Evaluators is too focused on helping animals, and objectionably view animal charities as instrumental to that end, instead of appreciating that the proper purpose of animal charities is to make their employees feel seen.

I guess that does pretty well sum up a core disagreement between EAs and the critics represented in this volume.

* * *

Something I find especially frustrating about the volume is a lack of clarity about when authors think that EA principles are ill-suited to achieving our goals of welfare-promotion, and when they instead reject these as the wrong goals and hold that we should instead be expressing care (by refusing to countenance hard trade-offs), prioritizing social justice, or maintaining purity (via non-association with corporations), for their own sakes. Those of us already convinced that these non-utilitarian values are misguided could then simply ignore those sections. But without this clarity, it’s hard to know how much of the book is really relevant to those who just want to do the most good. (My sense is: very little.)

For example, on p.196, a proponent of animal sanctuaries asks:

As we’re marching toward our shared and glorious vision of a world free from suffering, is it truly okay to ignore the mind-numbing suffering of those we could save in order to [save more via indirect means]?

Such full-throated endorsement of the identifiable victim bias doesn’t inspire confidence. (Obviously, if you don’t save more via indirect means, then you are ignoring the mind-numbing suffering of an even greater number of those we could save. Trade-offs exist, however determined these authors are to deny their reality.)

[Correction: I've deleted a passage from a different chapter that it turns out I misread; my apologies to that author for the unfair criticism. I should instead just say that my impression of the volume as a whole is that it contains a lot of anti-EA moral assertions without sufficient engagement with the reasons why EAs disagree.]

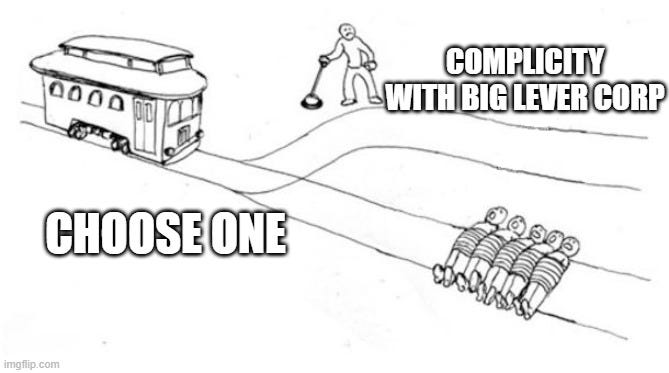

Yet another opposes the popularization of impossible burgers (p.18):

What have we come to when we call a diversification of business portfolios by these [agribusiness and fast food] companies—which are involved, through their caucus in Congress, in the dismantlement of environmental laws, human rights, and animal protection laws—a success for the animals, and even going as far as to offer “vegan” certifications to a Unilever product?

(I would’ve thought that any vegan product could be certified as such, but apparently it doesn’t count if it’s made by the wrong people?)

Now, it’s certainly conceivable that “complicity” with agribusiness will turn out to do more harm than good, and many of the authors in this volume speculate that this is so. But they don’t really provide evidence to support this claim, so if your priors (like mine) favour reform over revolution, again, there’s little here to change your mind. And given their evident independent opposition to pragmatic compromise “complicity”, listening to these authors on the consequences of pragmatic reform seems akin to listening to conservative catholics lecturing on the social harms of contraception. You know their mind was made up long before they came across the cherry-picked study that they’re now so keen to share.

Moreover, the editors seem to hint at the idea that their view could not possibly be supported on welfarist, utilitarian grounds. On p.xxviii, they write: “EA doesn’t have resources for fundamentally criticizing the pertinent capitalistic structures.” This sounds like a confession that their proposed alternatives do not offer a good bet for promoting overall welfare. (Otherwise, there would seem no principled barrier to making the case that their politics is a high-expected-value risk worth taking, just like x-risk reduction. It’s just… not very substantively plausible.) Only by abandoning EA principles, Crary writes, could EAs “finally [take] a step toward doing a bit of good.” (p. 246) Saving kids from malaria evidently isn’t worth a damn.

Anti-utilitarian moralizing seeps from nearly every page. One author denounces:

MacAskill’s morally repugnant call for an increase in the number of sweatshops in the Third World [as] merely the artifact of a utilitarian ideology incapable of recognizing exploitation as a moral or social problem. (p. 222)

Of course, there’s no critical engagement with MacAskill’s reasons. These authors don’t believe in reasons. They believe in righteousness.[1] Which brings us to…

The Ugly

At the end of the first chapter (p. 7), we’re told that:

[failing to fund] work being done by a Black activist in Black communities is upholding white supremacist ideas about which communities are worthy of support and which ones aren’t. In other words, it’s racist, plain and simple.

The second chapter tells us that featuring endorsements from attractive celebrities constitutes “body shaming, ableism, and sexism.” (p. 13)

From the third, we learn that “Normative Whiteness is cooked into the ideological foundation, because it focuses on maximizing the effectiveness of donors’ resources.” (p. 28)

And so on.[2] It’s like a caricature of delusional humanities professors invented to provide fodder to Tucker Carlson. Except it’s real. Apparently some people really think this kind of thing passes for argumentation.

Illogical reasoning is also present in other forms of “argument” found in this volume. For example, we’re told that rising consumption of animal products, during a time when EA funders gave over $144 million to animal welfare causes, “demonstrates that EA is not effective at achieving its purported goal of saving animals.” (p. 187, emphasis added.) The notion of slowing a rate of increase is apparently not within the sphere of logical possibility to this author. (Not to mention that the main EA strategies mentioned above would, if successful, lead to either (i) improved animal welfare, not reduced consumption, from corporate cage-free campaigns; or (ii) later payoffs, from alt-meat development.)

Or, from Lori Gruen (p. 255):

In a comment that clearly identifies EA’s inability to acknowledge injustice as bad, MacAskill writes, “I think that it is unlikely in the foreseeable future that the [EA] community would focus on rectifying injustice in cases where they believed that there were other available actions which, though they would leave the injustice remaining, would do more good overall.”

Clearly, if injustice does not receive lexical priority, this implies that it must not be bad at all! *facepalm*

On p. xxv, the editors tell us that:

EA’s principles are actualized in ways that support some of the very social structures that cause suffering, thereby undermining its efforts to “do the most good.”

That’s an awfully sneaky use of “thereby”. I would’ve thought it entirely possible (indeed, plausible) that you might do the most good by supporting some structures that cause suffering. (For one thing, even the best possible structures—like democracy—will likely cause some suffering; it suffices that the alternatives are even worse. For another, even a suboptimal structure might be too costly, or too risky, to replace. But you’ll find no consideration of such ideologically inconvenient ideas in this volume.)

Alice Crary argues (well, asserts) that “EA is a straightforward example of moral corruption.” (p. 226) Why? That remains unclear to me. But we are told that:

an Archimedean view deprives us of the resources we need to recognize what matters morally, encouraging us to read into it features of whatever moral position we happen to favor. (p. 235)

This is in contrast to Crary’s preferred view, on which only those with a “developed sensibility” can directly perceive the values enmeshed in “the weave of the world” (p. 235). Like, that EA funders should give her friends more money.

Epistemic Implications

This is precisely the anti-EA volume we would expect to see if EA were in fact doing everything right. We should fully expect maximizing welfare to generate complaints about “inequitable cause prioritization” (p. 82) from those who care more about social justice. We should expect affirmations of ineffectiveness, like the following, from those who lose out from competition:

It is unhelpful to think that you are searching for the single most effective way your money can be used. Instead, you are looking for a good way to support a project that aligns with your priorities, is well-run, and looks like it has a good chance of achieving its goals. (p. 107)

Another author urges that “we all need to reject the injurious intolerance of Effective Altruism in favor of a more modest and generous mode of relating to the projects of others.” (p. 125) Apparently it’s intolerant to prefer to give money to more effective causes over less effective ones. This is the “harm” that effective altruism does. You know, to the wallets of the authors and their allies.

Elsewhere, we’re informed that EA “misidentifies the biggest problems today as global health, factory farming, and existential threats” when really “the global poor suffer from adverse health outcomes because of capitalist social relations.” (p. 218)

For a moment, I wondered whether the low quality of this book might constitute positive evidence in support of effective altruism (“if these are the best objections they can come up with…”). Unfortunately, many of the authors seem so ideologically opposed to cost-effectiveness evaluation that I expect they would’ve written the same tripe even if there was strong evidence available that EA interventions really were worse in expectation. So I guess it’s just a wash.

The Crux of the Dispute

I previously suggested that EA may inspire backlash in part because it challenges conventional moral status hierarchies. There’s a certain kind of radical leftist for whom doing good outside of their preferred political framework is very threatening. (If we can address major global problems without a revolution, how are they going to recruit new acolytes?)

The overwhelming impression I got from this volume (especially the more “theoretical” contributions) is a sense of sourness that EAs aren’t blindly deferential to the social justice crowd, don’t share their priorities or perspective, and that if this competing ideology spreads it could do “grievous harm” to them and their movement. One author explicitly laments:

the over-valorization of billionaires and financiers in EA discourse, and a corresponding undervalorization of grass-roots activists and radicals. (p. 211)

(What if billionaires and financiers could actually do more good than grass-roots activists and radicals? This thought is verboten.)

Gruen similarly laments that EA priorities tend to “marginalize some of the most committed activists and their work.” (p. 261) This is taken to be self-evidently unjust.

Of course, for all I’ve said here it might be that social justice activists really are the best and most effective people in the world, in which case all their criticisms might be spot-on. But this book offers no independent reason to believe this. It’s just one big exercise in question-begging. Again, these complaints are exactly what we’d expect to find even if EAs were right about everything. So I don’t see how this volume advances the dialectic at all.

For what it’s worth, I find the worldview on offer in these pages incomprehensibly alien. It’s one on which answers to economic questions are best found by consulting “eco-feminists” rather than economists. That just doesn’t seem remotely plausible to me, and no reasons were offered in this volume to change my mind.

Generally speaking, I think economic growth and technological progress are good. (Crazy, I know!) As Kelsey Piper writes in The Costs of Caution:

Medical research could cure diseases. Economic progress could make food, shelter, medicine, entertainment and luxury goods accessible to people who can’t afford it today. Progress in meat alternatives could allow us to shut down factory farms.

Hastening such progress, while prudently guarding against existential (and other severe) risks, is—in my view—plausibly the best thing we can do for the future of humanity.

By contrast, an eco-doomer contributor to the volume confidently predicts that:

Effective Altruists will no doubt continue to see hopeful signs of incremental, quantitative progress in specific areas of policy—e.g., in extreme poverty or malaria reduction—right up to the moment when the entire system collapses, leaving billions to starve to death and all animal life obliterated. (pp. 218-19, emphasis added)

“No doubt!”

- ^

On p. 214, we’re told that EA “has wound up promoting radical evil”, for encouraging people to consider working in the US State Department.

- ^

Carol Adams even informs us that:

Sebo and Singer flourish as academics in a white supremacist patriarchal society because others, including people of color and those who identify as women, are pushed down. (p. 135, emphasis added.)

Maybe treading on the oppressed is a crucial part of Singer’s daily writing routine, without which he would never have written a word? If there’s some other reason to believe this wild causal claim, we’re never told what it is.

Thanks for this review, Richard.

In the section titled, "The Bad," you cite a passage from my essay--"Diversifying Effective Altruism's Longshots in Animal Advocacy"--and then go on to say the following:

"Another author tells us (p. 81):

(Of course, no argument is offered in support of this short-sighted thinking. It’s just supposed to be obvious to all right-thinking individuals. This sort of vacuous moralizing, in the total absence of any sort of grappling with—or even recognition of—opposing arguments, is found throughout the volume.)"

It sounds from your framing like you take it that I assert the claim in question, believe that the alleged claim is obvious, and hold this belief "in the total absence of any sort of grappling with--or even recognition of--opposing arguments."

With respect, I don't think your reading is fair on any of these fronts.

First, I don't assert the claim in question. The passage you (partially) cite actually reads "One might object that it is morally ill-advised to invest...", and what I'm trying to do in this context is to get behind why someone skeptical of certain EA cause-prioritizations might be worried that it is morally ill-advised given other considerations that you don't mention in your review. (I recognize that one has limited space in a review and can't get to everything.)

Second, I don't believe that the claim you misattribute to me is "obvious to all right-thinking individuals." Here are two bits of support for my explicit recognition (in the chapter) of my belief that right-thinking people might disagree:

(i) On pages 79-80, the pages immediately before the passage you cite, I consider the hope to "mitigate important but often neglected 'longtermist' concerns about suffering-risk", providing footnotes to an FAQ on s-risk, citations to work by MacAskill, Bostrom, and Ord, and gratitude to Dominic Roser for "helping me to see the complexity of this problem through the lens of intergenerational justice." I go on to say, "Though it is tempting, given the pressing concern of inequitable cause prioritization, to weigh the opportunity costs of funding such tech long shots only in terms of the interests of presently disadvantaged communities, there are also the interests of future disadvantaged communities to consider", citing Roser and Seidel 2017.

(ii) On page 80, about four lines of text before the passage that you cite as an instance of "vacuous moralizing", I say this: "A reasonable person could be forgiven, it seems, for judging the opportunity costs associated with possibly foiling a misaligned AI in fifty years to be too high, and for suspecting that these millions of dollars could be better invested elsewhere. (I should add that the same reasonable person might simultaneously conclude that it is nonetheless wise to devote some resources to mitigating s-risk; my intent here is not to try to minimize these serious risks, but to emphasize that significant investment in their potential mitigation, however important, is nonetheless a long shot with present opportunity costs worth keeping in mind.")

Third, the above two bits also seem to me to sit ill with the framing of my essay as "lacking any sort of grappling with--or even recognition of--opposing arguments." I may still be engaged in "vacuous moralizing" by your lights, and perhaps I've fallen short of your standard for "any sort of grappling". But I hope I've at least succeeded in recognizing the existence of opposing arguments (maybe I cited the wrong people or too few of them?).

On the bright side, those in this thread who are skeptical of steel-manning as a strategy for engaging critics will have no quarrel with you. :)

Thanks again for reading the piece and I'm sorry that it was a dispiriting experience!

Hi Matthew, thanks for clarifying that! I owe you an apology. The quoted passage jumped out at me as illustrating a trend that I was finding irksome about the volume as a whole, but I wasn't careful enough to double-check that my editorializing was a fair representation of your article in particular. I'll update my post with a correction.

Quick follow-up that I hope isn't too pedantic (but maybe is, despite my hope?). I just had a chance to check the correction itself on my computer (my phone wouldn't take me to the link for some odd reason) and noticed that, while the unwarranted criticism has been retracted, the misattribution itself has not. The set-up for the quotation still seems to read, "Another author tells us (p. 81), 'it is morally ill-advised to invest tens of millions...', which isn't technically true. I don't "tell" readers that "it is morally ill-advised..." by observing that "One might object that it is morally ill-advised..." any more than I would have told them "Keith kills it at Scrabble" had I written "One might wonder whether Keith kills it at Scrabble." Maybe that seems like a small quibble, but if my work is going to be used as Exhibit B in a section of a book review titled "The Bad," I want to be guilty of the alleged wrongdoing, ya know? :)

Thanks Matthew for engaging, particularly given that this post may not have been written in the most friendly way!

I feel confused about what your chapter is asserting then? Your chapter starts off with your two reservations about EA:[1]

These reservations seem pretty clearly consistent with the fragments that Richard excerpted. And in both cases, you go on to give additional argumentation about why these excerpted objections are correct.

For example with the "morally ill-advised" one you go on to say: "To make this worry more concrete in the context of the animal-focused applications of EA discussion in this book, consider the disproportionate toll that the ascendance of industrial animal agriculture has taken on communities of color in the United States, and on Black communities in particular." You then elaborate on these inequalities for several paragraphs, without using the "one might…" voice.

The excerpted fragments are also consistent with what I took the point of your chapter to be (EA should diversify away from food tech into outreach to black vegans, higher ed, and religious people). But maybe I am completely misunderstanding your point?

I am very sympathetic that readers will see meanings that writers didn't intend, but for what it's worth: yes, if you wrote "One might wonder whether Keith kills it at Scrabble", gave many pages of evidence supporting the claim that Keith kills it at Scrabble, and then concluded your chapter with a suggestion that we should send Keith to the Scrabble world championship, I would, in fact, think you are telling me that Keith kills it at Scrabble.

I'm paraphrasing lightly, hopefully this is still accurate

[TL; DR: I'm a little confused too, and this essay was an attempt (maybe a failed one?) to try to work out a "both/and" that would synthesize my fledgling sense that EA has something important to offer in spite of methodological idiosyncrasies, hermeneutic blindspots, and demographic challenges that seem seriously to limit its appeal and reach; and that grassroots advocacy work in various culturally influential communities that seem positioned to do great good (but are often lacking the resources to scale it and viewed with skepticism by some EAs) could benefit from EA-channeled resource-infusions.]

Hi Ben! That you have carried on with the "Keith kills it at Scrabble" thing gives me joy. An occupational hazard of doing philosophy is time sacrificed to fashioning examples calculated to seem like the effortless progeny of a rapier wit when in fact one struggles mightily and usually fails. I confess to lingering over Keith for a minute before I cut him loose, and to witness him flourishing in this comment thread even unto the Scrabble world championships...I am moist-eyed!

Before I go any further, let me confess in humility that I am a relative newcomer to thinking about EA and not very well versed in the lingua franca, so I hope that at least some of what I say is intelligible even if the words "priors", "counterfactual", and "expected value" are nowhere to be found! :)

Truthfully, I'm a little confused myself as to exactly what I'm trying to do in this essay (which is why there's all that hedging language throughout: one might this, one could that, "worries" and "reservations" rather than "objections" and "refutations," etc.). I think it's one of those "both/and" sorts of projects where I'm hoping--maybe too optimistically? maybe in vain?--that if EA diversifies the ol' methodological and cause-prioritization portfolios a bit, the whole movement and the world, too, will get more of what it wants and needs? Something like that? (By "movement" here, I've got animal advocacy in mind (the main focus of the volume), but given that my activist's imagination has been greatly shaped by the work of Carol Adams, Aph and Syl Ko, Christopher Carter and others, it's a holistic pro-flourishing/anti-oppression movement more than just a one-issue focus on animal advocacy).

Here's how I frame this "both/and" gesture in the first few pages:

"In what follows, I'll explain each of these reservations and then suggest some exciting new initiatives--institution-building in Black vegan advocacy, higher education, and religious communities--that could mitigate these reservations, energize and diversify the movement, and remain true to the EA method of supporting underexploited but potentially high-impact causes that produce non fungible goods otherwise unlikely to be funded." (77)

If this conversation is to continue, it might help for me to fess up to a couple of idiosyncrasies in my background that really complicate my outlook on these matters and have prompted me to search for a "both/and" in a situation where some seem to think we must choose between EA and grassroots approaches.

My methodological worries about EA are largely rooted in my training as a hermeneutic phenomenologist. Though I studied analytic philosophy in both undergrad and graduate school, I ended up doing some coursework in both places that raised serious concerns about Enlightenment approaches to method in the humanities and social sciences, especially in cases where science-envy in these fields generates overconfident appeals to objectivity and fixation on measurement as ways to try to corral the unpredictable vicissitudes of human history (or, worse, to dominate and exploit others (e.g., colonization (society/reason vs. nature/savagery), eugenics, etc.). Hans-Georg Gadamer's Truth and Method convinced me that there are many pre-reflective and ultimately immeasurable forces at play in the interpretive contexts that are always already shaping our understanding of things, and that--as a result--staying in touch with reality requires ongoing dialogue with others whose different hermeneutic situations and life experiences offer us a clearer vantage point than even the most rigorous self- or communal reflection could leverage on the hidden blindspots and unwitting exclusions of our own limited perspectives. After reading thinkers in the hermeneutic phenomenological tradition (like Beauvoir and Fanon) who extended these insights into their implications for matters of gender, race, and systemic/institutional injustice, I became a lot more sensitive than I had been before to the risks associated with methodologically and demographically homogenous communities (not just the risks of exclusion and oppression, but the risks of falsely presumed supremacy, impoverished thinking, and cultural stagnation and decline into which homogenous cultures can unwittingly descend--maybe some of the recent events around SBF could be viewed as cautionary tales in this register?).

One might think, given all of this, that I'd be an anti-capitalist. But it turns out my Dad is an economics professor who devoted his career to arguing that capitalism, while woefully imperfect, is the best approach we've found so far to meeting human needs and curbing human suffering in a world of scarcity (he did a lot of advisory work in the former Soviet Union and had a front row seat to some of the other approaches on offer in contrast to which capitalism, warts and all, looked much better to him). Dad was always beating the drum that the problem isn't capitalism per se, but the fact that--as a citizenry--we've failed to develop and evolve the moral sentiments and fellow feeling that would enable us to demand the proper things and create markets that deliver on those demands. He always said that the invisible hand would do a very bad job without a very good citizenry to set the parameters of its field of play, citing Adam Smith's claims that one could not understand The Wealth of Nations or pull off the project described therein without enacting the world of The Theory of Moral Sentiments first as the foundation.

So, despite having read a bunch of stuff (and having a bunch of corroborating experiences of those insights in the philosophical, religious, and advocacy communities of which I am a part) that inclines me to think we're all doomed if we don't become significantly more methodologically and demographically diverse in our approaches to social problem solving, I've also been heavily shaped by the beliefs that capitalism is the best we human beings have done so far in terms of providing systemic solutions to scarcity and that capitalism might be able to do much, much better if our methodological and demographic diversification efforts expand our consciousness and our problem solving skills so that we can demand better things from new and better markets. These experiences are obviously in some tension with one another, and I guess the cageyness of my paper is rooted in that tension. That tension also explains why I'm excited about organizations like Afro-Vegan Society, CreatureKind, and GFI, even though they're doing very different sorts of things.

Gosh. That was way, way too long and rambling. Better add a TL;DR before I sign off. Thanks again, Ben, for getting me to think harder about what's going on here! I hope it's a little clearer what I was trying to carry off.

Understandable! I've cut the passage entirely, since as you say it isn't really fair to exhibit your work in that section of the review.

Thanks, Richard! I appreciate your posting a correction.

Just wanted to say that I appreciate you taking the time to respond so politely to quite a critical review.

Thanks for this expression of gratitude, Chris! For better or worse, with an average philosophy paper getting a readership of like 8-12 people (including sympathy reads from family members?), I tend to view even the most scathing criticism in the frame of “SOMEBODY READ IT! Victory is mine!” 🤣👍🏻

I think it is great that you, one of the authors of The Good it Promises, the Harm it Does, have taken the time to engage in constructive discussion with effective altruists.

Here are a few thoughts I had after reading your essay. The advantage of focusing on students in higher education might be that they are more likely to sympathize with veganism and thus more likely to actually become vegan than people from other groups are. On the other hand, the impact of additional resources in this area might be lower because students are probably more likely to already be aware of the arguments in favor of veganism, and might already have more knowledge about healthy, tasty plant-based food, and thus a lot of students might have become vegan anyway, even without reaching out to them. Conversely, getting people from religious and/or Black communities to go vegan might be more challenging, but the impact might be very high because, as you rightly point out in your essay, financial support for animal advocacy outreach to religious and/or Black communities is neglected.

Overall I think your essay raises great questions and I really hope that effective altruists will engage with them.

Hi again, Maxim! Thanks for your patience.

Your point is well taken about the risk that additional resources in higher education settings might be redundant given that college students are perhaps more likely than the general population already to be "aware of the arguments in favor of veganism." I think that this would be a serious concern if "awareness of the arguments in favor of veganism" alone were sufficient to support behavioral change over the long-term.

In my experience, however--and I think the most recent social scientific evidence supports this observation, too--"awareness of the arguments" is generally not enough for many even to motivate serious experimentation toward behavioral change much less to support it over time. For many people, indeed, exposure to the arguments can have a counterproductive effect, in that data and argumentative support for positions they find threatening trigger identity-protective cognition that leads to a doubling-down on the attitudes and actions perceived as under threat (Ezra Klein's Why We're Polarized has some really helpful, accessible discussions of this phenomenon and its effects on people's ability to process data and arguments).

How do we mitigate the serious threat to cultural change posed by identity-protective cognition? I'm intrigued by the strategy of implementing slow-releasing changes in the epistemic atmosphere that collectively serve to defang and normalize the data and supporting arguments so that they can be received without triggering identity-protective cognition. In other words, by creating environments that help people both pre-reflectively and communally to take the data and supporting arguments in stride and maybe even find them intriguing or inspiring, we can circumvent the threat-detection response that closes many people off to attitudinal and behavioral change.

By pre-reflective environmental conditioning, I have in mind giving people lots of opportunities pre-reflectively to intuit that something is non-threatening, credible, and maybe even cool without having to engage in an argumentative way that threatens one's identity. By communal environmental conditioning, I have in mind giving people lots of opportunities to get social and cultural support from similarly interested people and organizations in the event that their interest is piqued.

I'm hard-pressed to think of a better place to cultivate both pre-reflective and communal environmental conditioning than the hallowed halls of institutions of higher learning. Anyone who is paying attention to the higher ed culture wars in American institutions likely already understands the ripeness of this environment for shaping people's values and behaviors over the long term. Students come in chomping at the bit to get out from under their parents' influence and values, so they're highly open to suggestion. For 4+ years, they are surrounded on all sides by opportunities to expand their consciousness and expertise--not just explicitly by going to classes and talks and lectures, but pre-reflectively by breathing in an atmosphere that normalizes all kinds of differences that may have seemed anything but normal in one's previous day-to-day life. There are charismatic professors, compelling student leaders, amazing vocational training and networking opportunities. Unsurprisingly, the well-funded programs that institutions innovate, support, and proudly advertise are the ones that often generate the most interest, excitement, and participation.

So imagine what could happen if we got serious about accelerating and scaling the vegan-friendly cultures that are already seeded in higher education. Generally speaking, the faculty presence and student clubs and extracurricular opportunities in many places are already there on the ground, but are both decentralized and underfunded. In a lot of cases, scaling these cultures (or at least nudging them in the direction of scalability) could be as easy as giving a substantial lead gift for an institute or center--let the university decide how to mission-fit and brand it for galvanizing its alumni and current students (sustainability? creation care? human/animal studies? food systems? green economy?). The director(s) of the center and key faculty and administrators, then, audit everything that is going on around and tangent to these issues, build a central institutional hub to connect and empower the different intermeshed programs and opportunities, and then help faculty to build out curricular programs (majors, minors, certificate programs, themed dorms and cohorts, honors programs, etc.) and student life to build out supporting extra-curricular and cultural programs, using funding opportunities and internal grant-making programs to nudge everyone who's got anything going that is tangent to food-systems stuff (which is almost everyone, in the end) to ramp up the facets of their work that feed into creating ferment around changing our food system. Over time, there will be lots of vegan-friendly people, classes, clubs, receptions, student groups, educational and extracurricular programs, even restaurants and businesses in the town that support the ever-growing populations of students who come to do this work. People who come to the university thinking that going vegan is silly or threatening will see how exciting and transformative it is, both individually and culturally and will be much more receptive to the arguments (if indeed they even need to hear them at all; once the atmosphere is where it needs to be, the arguments themselves become redundant, which is probably better anyway given how post-hoc the average human being's relationship to "the arguments" is anyway).

If it seems far-fetched that such a thing could happen, consider how quickly (in the grand scheme of things, at least) universities have shifted the national and international narratives around many other cultural and political topics and movements. And of course, the history of the agriculture industry's involvement in the shape of higher education gives us a compelling case study that the university has already been used in precisely this way to shape and change the cultural and political landscape that has allowed the current food system to deflect criticism and put off urgently needed change.

Two exciting non-profits that are pioneering this sort of holistic approach to engaging the whole human being and providing support that goes beyond just "exposure to the arguments" toward life- and institution-building are Afro-Vegan Society ( https://www.afrovegansociety.org/copy-of-about-avs ) and CreatureKind*( https://www.becreaturekind.org) . These orgs primary constituencies are Black and Christian audiences, respectively, but their holistic approaches to creating atmospheric shifts in the culture and building positive supporting institutions (rather than just handing out pamphlets with all the bad news) are valuable models that could be replicated in lots of different contexts. Also, the Good Food Institute** is engaging higher ed directly with its "Research Centers of Excellence" program: https://gfi.org/solutions/building-interdisciplinary-university-research-centers-of-excellence/.

*I am on the board of directors for CreatureKind.

**I have a family member who works at The Good Food Institute.

Thank you, Matthew, for writing this fantastic comment. The arguments from your essay seem a lot stronger to me now that I take your comment into consideration. It is true that higher education can be a great force for positive social change. As far as I know, many of those involved in emancipatory social movements were educated at university, and this can be no coincidence. And I wholeheartedly agree that getting people to go vegan is not a matter of telling them the arguments in favor of veganism, even if they are not aware of these arguments yet. We may indeed be far more successful if we can first get people to experience how vegan food can be just as delicious and healthy (if not more) than non-vegan food, and then get them to go vegan themselves. This is, in any case, how it worked for me: I was already a vegetarian, so I knew that you could eat great food without eating meat, and after recently discovering tofu, vegan mayonaise, coconut-based dairy yoghurt replacement and vegan chocolate desserts (all of which I had almost never eaten before), it became clear to me that I could eat great food without dairy and eggs too, and so I became a vegan too. Of course, I had already been (vaguely) aware of the arguments in favor of veganism for quite some time, but back then, I just couldn't picture myself enjoying vegan food. Indeed, we need to get people to experience how great vegan food is, and the proposals you discuss in your comment can definitely contribute to that.

Thanks so much for this positive feedback, Maxim, and for the reflections on potential impact! I really appreciate your taking the time to share them!

I have some additional thoughts, but no time at the moment to share them! So, gratitude for now and a promise to circle back when time permits! :)

It is sometimes hard for communities with very different beliefs to communicate. But it would be a shame if communication were to break down.

I think it is worth trying to understand why people from very different perspectives might disagree with effective altruists on key issues. I have tried on my blog to bring out some key points from the discussions in this volume, and I hope to explore others in the future.

I hope we can bring the rhetoric down and focus on saying as clearly as possible what the main cruxes are and why a reasonable person might stand on one side or another.

I agree with this. But in order for constructive debate to happen, the authors of this book will need to make better efforts. It would be great to see any of them reach out to effective altruists and engage in debate, but as far as I know, this has not yet happened at all

UPDATE: Matthew C. Halteman now appears to be the first author of The Good it Promises, the Harm it Does to have posted on this forum and has engaged in constructive discussion with the author of this topic. This is great! I'd love to see more like this!

Hi David, yes, I've appreciated your blog commentary on these issues, and would recommend that people read that over the book itself!

Thanks Richard -- I've appreciated your comments on the blog!

It would be worth cross posting each blog post here!

How about a blog update in a month or so about the post series I've written so far, lessons learned, and future directions, posted to the EA Forum?

Thanks! I always appreciate engagement and would be very happy to see any of my posts discussed on the EA Forum, either as linkposts or not.

I need a bit more independence than the EA Forum can provide. I want to write for a diverse audience in a way that isn't beholden primarily to EA opinions, and I want to be clear that while much of my blog discusses issues connected to effective altruism, and while I agree with effective altruists on a great many philosophical points, I am not an effective altruist.

For that reason, I tend not to post much on the EA Forum, though I do try to comment when I can. I'd be happy to comment at least to some degree on any linkpost, and I'm always very responsive to comments on my blog.

I appreciate this can be a bit frustrating, but I need to be clear about who I am and who my audience is.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply. That makes sense. I don't consider myself an EA, and read EA Forum 80% out of intellectual interest, 20% out of altruistic motives, so I'll leave my end of the conversation here (and perhaps subscribe to your blog!), but from the upvotes on your suggestion of a blog update, seems like it met with significant interest among EA Forum readers, so I'd encourage you to do that!

Agreed, and will do!

Your discussion of the 'good' in the book doesn't mention a part of Amia's foreword that I think is a fairly powerful critique (though far from establishing "effective altruism is bad as currently practiced" or anything that strong):

'These [above] are some of the questions raised when the story of Effective Altruism’s success is told not by its proponents, but by those engaged in liberation struggles and justice movements that operate outside Effective Altruism’s terms. These struggles, it must be said, long predate Effective Altruism, and it is striking that Effective Altruism has not found anything very worthwhile in them: in the historically deep and ongoing movements for the rights of working-class people, nonhuman animals, people of color, Indigenous people, women, incarcerated people, disabled people, and people living under colonial and authoritarian rule. For most Effective Altruists, these movements are, at best, examples of ineffective attempts to do good; negative examples from which to prescind or correct, not political formations from which to learn, with which to create coalition, or to join.'

(Got the quote from David Thorstad's blog: https://ineffectivealtruismblog.com/2023/02/25/the-good-it-promises-the-harm-it-does-part-1-introduction/)

Now, we can debate the extent to which this is true (most EAs are actually pretty sympathetic to animal rights activism I suspect, Open Phil. gave money to criminal justice reform etc.). But insofar as it is true, I take it the challenge is something like: 'what's more likely, all those movements were in fact ineffective, or you're biased demographically against them'. And I think the bite of the challenge comes from something like this. Most EAs are *liberal/centre-left* in political orientation. So they probably believe that historically these movements have been of very high value and have produced important insights about the world and social reality. (Even if we also think some other things have been high value too, including perhaps some many people in these movements disliked or opposed.) So how come they act like those movements probably aren't still doing that? What changed?

I think there are lots of good responses that can be made to this, but it's still a challenge very much worth thinking about. More worth thinking about than gloating/getting angry over the dumbest or most annoying things the book says. (And to be clear, I do find most of the passages Richard quotes in his review pretty annoying.)

I think that this would be an accurate characterization of early effective altruism which was explicitly pushing back against these kinds of interventions.

I suspect what happened is as follows:

Because people in EA tend to swing one way or the other pretty heavily, it means that there hasn't been a large enough group within EA to co-ordinate much political action for the purpose of addressing poverty.

There is an exception in that animal rights folks seem more open to political interventions, but I suspect that's related to the influence of left thought within animal rights as a whole.

Although long-termists have drawn lessons from these movements. They're just less relevant to AI Safety than to global poverty or criminal justice reform.

Yes, fair point! Though it's a bad sign for a book if the best thing about it is the foreword by a different author.

My overall judgment is that the book itself is not worth reading, and anyone interested in ideas from this quarter would do much better to just read David Thorstad's commentary (which is much better, and less aggravating, than the book itself).

I agree that this book rightly asks the question whether effective altruism is not undemocratically excluding certain valuable perspectives and movements. However, I believe the book's authors fail to provide many specific and convincing examples of people that effective altruists should listen more to (with the exception, possibly, of those who run farmed animal sanctuaries, and I must add, of those who advocate veganism to students in higher education). This is unfortunate, because I think the book's authors are probably right when they suggest that effective altruism should listen to more diverse voices.

Thanks for writing this up Richard. There was a plan a few months ago on the forum to divide and conquer the book, and maybe post up a joint review, but it fell by the wayside. That's partly due to real-life being higher priority, but I also got ground down by the hostile nature of the book - and slogging through it to reproduce the arguments just wasn't going to happen. I welcome attempts to steelman parts of this book[1], or associated works, as I do think it is important for EA to understand and to engage with our critics.

I think there are some good bits in there that are worth understand where critical/leftist challenges to Effective Altruism come from. Srinivasan's foreword is a good outline of a 'low decoupling' challenge to the analytic philosophy approach that's core to a lot of EA thinking, and I found Simone de Lima's Chapter 2 the highlight of what I read - I think that the Chapter title does it an injustice. I'd encourage people to read David Thorstad's review of that chapter for a charitable/steelman reading of it. In many places, especially the end of Chapter 17, the contributors are clear that they view Capitalism as the primary source of evil - and that this is a self-evident moral fact, and it's a pretty clear crux to understand their point-of-view.

But yeah, a lot of it is just... really, really bad. I'm going to single out Crary's Chapter 16 "Against Effective Altruism" here. I believe it's mostly a reproduction of a previous essay (perhaps with small changes) that are already in the public domain.[2] Some points that are especially egregious to me:

I honestly think that Crary's article might be one of worst anti-EA articles I've read and boy is that saying something, because there are a lot. As I said in the intro maybe someone can make a stronger case for it, it definitely riled me up, but it may honestly just be as bad an article as it seems.

There is one final point worth considering though. There's a meme in some rationalist-spaces that EAs are "quokkas" - which I don't like[3], but it may have a kernel of truth if we're so "turn the other cheek, don't fight noise with noise" etc. I want to suggest that EA should take a stronger response to this kind of critique in the future. I think the current line is to just not respond to this kind of thing? But I think we're big enough as a movement where our criticism is also noticeable, and will on its own persuade critics. I think it was completely avoidable for someone as prominent as Timnit Gebru to call us all fascists. Instead, we should be pushing back on prominent criticisms that are clearly wrong and beyond the pale - and do so clearly but forcefully. In short, in cases like this, we may have too many Darwins and not enough Huxleys.

Hopefully we can find someone in addition to Thorstad willing to give it a go?

The earliest source I could find was this talk, but the article also appeared in Radical Philosophy in 2021.

Clarification - I don't like the use of this term pejoratively. Quokkas themselves are objectively adorable.

Small disagreement: if someone genuinuely believes some work to be morally corrupt, I'd prefer they go out and say it rather than hide behind more euphemisms. I don't think it's structurally any different from e.g. calling factory farming "evil" or AI capabilities research "terrible for the world."

Part of this might just be a norms difference: in most fields regular uses of morally laden language is uncommon, often counterproductive, and comes across as aggressive. But Crary is a moral philosopher, and at their best, the job of a good moral philosopher[1] is to regularly interrogate the nature of good and evil.

not saying that she's necessarily a good one

I liked your comment but disagree with this part:

I think "steelmanning" a view is not something we should generally strive to do, and I wish people stopped treating the inclination to "steelman" an opponent as a sign of epistemic virtue. "Steelmanning" is a pretty poor hueristic for many reasons, including that (1) it lacks the resources to distinguish views that may deserve to be steelmanned from views that ought to be dismissed as nonsense; (2) it is an instance of countering a potential bias in one direction with a bias in the opposite direction, which will often result in excessive correction, insufficient correction, or unnecessary correction; and (3) it often impedes understanding and communication, since the "steelmanned" version of a view may bear little resemblance to what its proponent intended.

As superior alternatives to "steelmanning", I would suggest trying to pass the ideological Turing test, writing a hypothetical apostasy, and being willing to turn disagreements into bets (a practice which, to paraphrase Dr Johnson, "concentrates the mind wonderfully").

I disagree with this take, and fortunately now have a post to link to. I think steelmanning is a fine response to this situation.

I think your (3) is the one I spend the most time digging into in the post, and I feel quite confident is not a good reason not to steelman.

Re: 1&2, I agree I'm, like, not that bullish on getting a bunch of value from this book, but it looks like a bunch of people have already gotten value from the theme of excessive focus on measurability. And generally I want to see more constructive engagement with criticism, and don't think "eh, low prior on it working" is a good critique of a good mental move.

Thanks. I hadn't seen that post, nor most of the arguments against steelmanning that Rob Bensinger mentions. I thought I was expressing a less popular view than now seems to me to be the case. I found it particularly interesting to read that Holden Karnofsky finds it unsatisfying to engage with "steelmanned" versions of his views.

I agree with you that steelmanning in the context of a discussion with others or of interpreting the views of others is importantly different from steelmanning in your own inner monologue, and I think the latter may be justified in some cases. Specifically, I think steelmanning can indeed be useful as a heuristic device for uncovering relevant considerations for or against some view as part of a brainstorming session. This seems pretty different from how steelmanning is typically applied, though.

I think steelmanning is bad for understanding and engaging with your critics, but is still useful for engaging with criticism, and for challenging and refining your own ideas.

We ought to have a new word, besides "steelmanning", for "I think this idea is bad, but it made me think of another, much stronger idea that sounds similar, and I want to look at that idea now and ignore the first idea and probably whoever was advocating it".

Yeah, like Linch, I don't think there's anything wrong in principle with making a charge of "moral corruption" or other harsh criticism. But it needs to be supported; the problem with Crary's piece is just that it's abysmally argued and substantively deeply unreasonable.

I think you're misreading "morally corrupt" here. Morally corrupt in the left usually refers to purity politics and moral contamination rather than corrupt is bad. This is common in left wing parlance.

I haven't read the chapter or the book, but something like this just seems pretty plausible to me. By disproportionately featuring people filtered on the basis of a lookist[1] selection process (e.g. their popularity in lookist industries, or partially directly based on how attractive we think they are to us or to society), we may be condoning and/or perpetuating (societal) lookism, and increasing its harms. And lookism of course overlaps with "body shaming, ableism, and sexism", e.g. people discriminate on the basis of how disabilities or other conditions look, which is ableist, and women and girls seem to be more often the targets of lookism and body shaming, which is sexist. By supporting a specific standard of beauty, we may invite comparisons to it, and so possibly body shaming.

However, featuring any attractive celebrities at all doesn't necessarily seem lookist. OTOH, it could be that attractive celebrities are so rare in the population we should be sampling from (and it's not clear what that is) that even featuring one would be very unlikely to happen other than through lookism at some step.

My guess is that our contribution to lookism here is very small relative to the impacts for animals (whether good or bad for animals).

I wonder if it would be acceptable to them if we offset our contributions to lookism (and/or "body shaming, ableism, and sexism") by supporting work against it, too. I'd guess it wouldn't be that costly to do, if fully offsetting just means not increasing lookism on net, rather than preventing every harm of lookism we'd (foreseeably?[2]) cause.

Discrimination on the basis of physical attractiveness against those considered less attractive or in favour of those considered more attractive.

Trying to prevent every harm of lookism we'd cause, including unforeseeable ones, probably leads to decision paralysis, due to butterfly effects.

I think these are indeed successes overall, but I can imagine being more concerned about vegan-washing, humane-washing or otherwise legitimizing bad stuff a company does and improving their reputation and nonvegan/inhumane sales by applauding them for the little good they do or small improvements they make. The profits made off vegan products by non-vegan companies can also be reinvested in harmful products, at the same company or by shareholders in other nonvegan products, or to undermine "environmental laws, human rights, and animal protection laws". Of course, the profits can be reinvested into more vegan stuff, but we'd expect a greater share of reinvestment in vegan products from vegan companies.

Plus, I think products can still be labeled as vegan even if literal human slavery/forced labour was involved in their production (or at least wasn't certified not to be involved, from regions/industries of concern, like cocoa production). I don't think we should consider human slavery to be vegan.

So, it could cause harm, which may be of concern even if the benefits seem greater, and, at least a priori, it could even cause more harm than benefit.

But I disagree with them (or at least what I expect they're arguing; again I haven't read any of the book, although I've read Crary's critiques elsewhere), because I think benefits can outweigh harms, the numbers actually matter, and the specific harms they worry about seem small in comparison to the more direct benefits (the effects on farmed animals from people buying vegan products instead of nonvegan ones), and they might even have the sign wrong for the harms.[1] Some similar points here: https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/foundational-questions-summaries#momentum-vs.-complacency-from-welfare-reforms.

Also, brand recognition could be important. I'd guess vegan items from large nonvegan companies would replace more animal products than vegan items sold by vegan companies, because the former sell more among those who aren't committed to veganism than the latter, and we don't get as much out of targeting committed vegans.

The more a company is invested in vegan or more humane products, the less their profits depend on opposing them and laws protecting animals, and the more likely they are to actually support animal protection laws, even just to avoid being undercut by less humane companies (e.g. cage-free eggs vs caged eggs). It's not even clear counterfactuals matter to them; maybe just participating in a system that cause harm, even if your particular participation has no expected effect on how much harm is caused by that system (or even reduces it?).

About this footnote:

============================

Carol Adams even informs us that:

Maybe treading on the oppressed is a crucial part of Singer’s daily writing routine, without which he would never have written a word? If there’s some other reason to believe this wild causal claim, we’re never told what it is.

=============================

Here's a potential more charitable interpretation of this claim. Adams might not be claiming:

"Singer personally performs some act of oppression as part of his writing process."

Adam's causal model might be more of the following:

"Singer's ideas aren't unusually good; there are lots of other people, including people of color and those who identify as women, who have ideas that are as good or better. But those other people are being pushed down (by society in general, not by Singer personally) which leaves that position open for Singer. If people of color and those who identify as women weren't oppressed, then some of them would be able to outcompete Singer, leaving Singer to not flourish as much."

This is a pretty good review that highlights the biggest problems with this book quite well. I was also annoyed by the lack of good arguments throughout the book. This book feels like a missed opportunity in two senses.

First, it seems like a missed opportunity to collect actually impressive criticisms of effective altruism (which I believe very much can exist). For example, many authors of this book suggest effective altruism is problematically capitalist, which could be an interesting critique, but in my opinion they barely offer any interesting arguments to support this critique. The same thing applies for the critique that effective altruism's approach to animal advocacy is ineffective, which is another claim that is at once central in the book yet not adequately argued for.

Second, it seems like a missed opportunity to create a meaningful contribution to the debate on effective altruism. As David Thorstad pointed out, the authors of this book clearly have quite different worldviews and backgrounds than many effective altruists do. It is admirable that Thorstad tries to overcome this obstacle to debate by reading this book as charitably as possible so as to convince effective altruists not to dismiss it all too quickly. However, most of the authors of this book seem to make almost no serious effort to make themselves clear to people who do not already basically agree with their views. I find it very ironic that Amia Srinivasan writes in the book's foreword that

However, as of writing this, there have already been four posts on this forum to discuss this book (the above topic, a discussion of the book, a topic about a reading group for the book, and a post about the book before it was even published).

Conversely, as far as I am aware, none of the 22 authors who have contributed to this book have ever attempted to engage in conversation with effective altruists (on this forum or elsewhere).Matthew C. Halteman, one of the book's authors, has had constructive discussion with the author of the above post! Even if I think the book's essays were quite flawed, I can still imagine constructive debate taking place between effective altruists and the book's authors. But this will require more effort on the part of the contributors to the book.Other than that, I had a bunch of smaller issues with this book. Fifteen of the book's seventeen essays focus mainly or exclusively on effective altruism's approach to animal advocacy, but this choice is never justified. This focus is not bad per se, especially considering how compared to global health and x-risks, animal advocacy is relatively neglected in effective altruism. But it is quite misleading for a volume that promises to provide general critiques of effective altruism (the book's editors claim that it is "the first book-length critique of Effective Altruism"). The book's editing overall could have been far better, anyway. I felt like many of the essays made the same points, and a lot of sections were rather irrelevant to effective altruism. This was especially troubling in what I think is one of the worst essays of the book (5. 'Who Counts?') which was basically just a lengthy history of US wildlife conservation, followed by the vague and tendentious claim - of course without good arguments in support of it - that effective altruists treat animals like objects, in the same way that hunting lobbyists historically have done.

To the book's credit, I think the final essay (17. 'The Change We Need') was surprisingly good, and I think it rightly emphasizes that reforms should always keep an ideal in mind. When they do not, they risk merely making the whole problem worse. But I do not know enough about animal advocacy to know whether effective altruist animal advocacy actually lacks vision.

I agree with Thorstad that effective altruists should engage with what this book's worth anyway, even if that is certainly not easy, considering all the book's flaws.

This is an aside, but that is almost certainly false, right? Larry Temkin's Being Good in a World of Need was published last year (and seems, from skimming it, like it gets a lot of the things you mention right -- for example, it does engage in dialogue with EAs).

Thank you for pointing this out! From what I can tell, Temkin's book also isn't really meant as a book-length critique of effective altruism, although it does criticize aspects of it. It also looks like his book focuses only on effective altruism's approach to global health and development, not on the other cause areas or the effective altruism movement as a whole. The claim that The Good it Promises, the Harm it Does is "the first book-length critique of Effective Altruism" is still wrong though, because I think that book simply can't be considered a 'book-length critique of effective altruism' if it almost exclusively focuses on effective altruism's approach to one cause area (in a rather limited way too - I felt like the book's authors did very little effort to explain the arguments used by organizations like Animal Charity Evaluators, I found that rather unhelpful).

It looks like Temkin has the same concerns about effective altruist charities that other so-called 'aid critics' (like William Easterly, Dambisa Moyo and Angus Deaton) seem to have, so I'm not sure how original the book is in that respect. Either way I'm not going to read it, because it looks very long and complicated and I'm not sure how much of it is actually relevant to effective altruism. I do think I might check out parts of Temkin's lectures on which his book is based, the lectures can apparently be listened to online here. Interestingly, William MacAskill wrote a very sharp critique of Temkin's work.

Just putting up a link of this previous post about this book, on which there was quite a bit of discussion in the comments.

The following comment was initially intended to be some combination of synthesis, steelmanning, "translation" into EA concepts, and riffing on the result. It's gone more heavily into the last two categories as I have written it. It's possible that some or even all of the authors wouldn't agree with how I have translated/riffed on their concerns. I've deliberately not attempted to reference specific articles for that reason.

I do not have object-level opinions of any significance in the animal-welfare space, and I do not indentify as a member of the ideological left. I don't have a clear opinion on whether EA should act differently in the animal-welfare space. However, I do think the book's contributors at least indirectly touch on some broader themes that are worth reflecting on.

How Farmed Animal Welfare Might Be Different

One key theme of the book seems to be an argument that EA methodology is reductionistic -- including that EA's cost-effectiveness analyses cannot capture the complexity of the world particularly well (especially in diverse cultural contexts), that a heavy focus on utilitarianism fails to capture all the dimensions we should be evaluating on, and so forth. Some of the authors seem to advocate for what I might call methodological diversification -- those authors don't necessarily seem opposed to EA-style interventions, but don't think animal advocacy should put too many vegan egg-substitutes in that (or perhaps any) basket.

It occured to me that how we think about methodological diversification could be different in farmed animal welfare than other cause areas. In (e.g.) global health & development, EA spend is a small fraction of total spend in the cause area. So EA GH&D work is relatively focused on what the other funders have missed or undervalued, and the methodological diversity in GH&D comes predominately from what non-EA funders (e.g., Gates, governments) do. You can think that EA-favored projects and frameworks fail to measure and evaluate a lot of important outcomes, or that they give more credence to utilitarianism than warranted, and still think they are the best use of your marginal charitable dollar. In some other areas, EA may be the only actor, and so there is no risk of actively displacing pre-existing approaches.

I don't have a good sense of how large EA funding is a percentage of the entire farmed animal welfare (FAW) funding world. However, it seems plausible that, given how underfunded FAW has been historically, EA functions as a big fish in what is a rather small pond. And many of the authors seem to view EA in that light. Moreover, much existing non-EA funding may be bound as a practical matter to existing work, so it's plausible that an large proportion of the FAW funding potentially available for new or expanded work may be EA-flavored even if it's not as large in absolute terms.

Thus, the FAW context causes us to reflect on whether we think there is a limit on the proportion of charitable endeavor in a given cause area that should be conducted according to EA principles, and whether not disrupting methodological diversity becomes an important consideration at some point.

On Skepticism of Big Fish

EAs spill a lot of digital ink about epistemics. I wonder if a sizable fraction of the authors' concerns about and criticism of EA relate to epistemics -- what are the purposes of the FAW movement, and how can they best be achieved? Who decides the answers to those questions, and how?

Like most attempts at doing good, FAW needs a framework of ethical systems and values against which to evaluate its efforts. Where should that come from? I think the authors would be much more comfortable with answers like "the viewpoints of people who have made sustained and significant personal sacrifices for FAW" or even "a survey of faculty in philosophy departments" rather than giving much weight to "the views of a few major EA funders and their agents."

I'm sure most of the authors had thought about utilitarianism as it relates to animal advocacy before EA got involved; Peter Singer wrote a while ago, and by my count six of the contributors hold positions in philosophy departments (plus two in religious studies). It's not unreasonable for them to doubt that the increased influence of utilitarianism on what gets funded in FAW was primarily driven by advances in utilitarian thought or by its increasing acceptance by a broad swath of society.

If you're sympathetic to EA ways of doing things, then having EA firepower in a cause area you care about is a good thing. If you aren't sympathetic, then you are probably worried about the effect of that firepower on the epistemics of your cause area. If that cause area is FAW, you probably don't think it healthy that the power wielded by a small group of people (wealthy capitalists and their agents) has an outsize effect on what the FAW movement does -- both now and in the future. Stated another way, you probably don't think that what major EA FAW donors think should update you much at all on what the epistemics of the FAW movement should be.

And this is consistent with how we might think about the epistemic implications of New Big Fish in general, behind a veil of ignorance of sorts (i.e, without knowing whether their perspective is better or worse than the mix of existing perspectives in one's cause area). We'd likely conclude that their viewpoints shouldn't change cause area epistemics much at all, because there is no a priori reason to think the New Big Fish knows better than the greater number of other participants.

A thought experiment: imagine someone lurking the Forum suddenly died and left Open Phil-level money in their will, restricted to the pursuit of effective altruism in a cause area that is currently viewed as second-tier and/or with a methodology that is currently viewed as second-tier. What would the likely effects on EA epistemics be? My guess is that, within a decade, people would think the cause area or methodology was significantly more important / more sound than they would have thought in the absence of the lurking benefactor. In other words, throwing lots of money around tends to alter epistemics in practice. Although it's possible that the hypothetical mysterious lurker knew better than the community consensus, it's more likely that they were acting as a unilateralist and generated net harmful changes in EA epistemics.

The Unilateralist's Curse

Although perhaps not clearly stated as such, I think there is a kernel of an argument about the unilateralist's curse in the book that goes something like this:

My takeaway would be: when one is entering a new cause area with a large pocketbook, one should be careful to consult with existing stakeholders about proposed new projects, and listen carefully to any concerns they have about downside risk. (I don't know whether this happened in FAW or not.)

Thinking about the Long Term

Considering the effects of EA on the broader FAW ecosystem is particularly important to the extent that neither we nor the authors know where EA will focus its resources in a decade or two. For instance, it's plausible that more and more resources will flow to longtermist causes.

Apart from EA, FAW is most likely to draw funding and workers from communities that are rather left-focused in orientation. So, to the extent that EA's long-term commitment to the field isn't ironclad, it should be particularly careful to ensure that -- if it exits or sharply reduces investment -- the field is left in a position where it can carry on with the resources it has available to it. For instance, it would be bad for EA to transform the FAW field into one focused on working with corporations (e.g., corporate crate-free campaigns, alternative protein), to such an extent that there is a loss of institutional memory about other approaches, and then leave.

A Lesson for Each Side?

Interestingly, I think some of the lessons to draw from the book potentially apply to both sides (albeit to different extents and in different ways).

One suggestion is that, when critiquing those with different methodological commitments, one should always hold the mirror up to yourself as well. For instance, the author of the main post suggests a conflict of interest on the book authors' part, suggesting that at least some of them are reacting to threats of harm "to the wallets of the authors and their allies." I think it's proper to consider that the authors may have personal reasons for their positions -- many have invested significant portions of their careers into that work and presumably draw a great sense of purpose/meaning/fulfillment from it. (I doubt many people in FAW are getting rich off the work, though!)

However, EAs should recognize that they have their own personal interests as well and are -- well, human (i.e., not dispassionate dispensers of utilons). For example, many people who have done well in a capitalist system are at higher risk of underrating arguments that capitalism is the root of much harm. And it's common to care a lot about how much impact you are personally generating, which could potentially bias people into favoring top-down solutions rather than taking a more indirect role of supporting grassroots activism.