All posts

Today, 25 July 2025Today, 25 Jul 2025

Today, 25 July 2025

Today, 25 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Quick takes

Act utilitarians choose actions estimated to increase total happiness. Rule utilitarians follow rules estimated to increase total happiness (e.g. not lying). But you can have the best of both: act utilitarianism where rules are instead treated as moral priors. For example, having a strong prior that killing someone is bad, but which can be overridden in extreme circumstances (e.g. if killing the person ends WWII).

These priors make act utilitarianism more safeguarded against bad assessments. They are grounded in Bayesianism (moral priors are updated the same way as non-moral priors). They also decrease cognitive effort: most of the time, just follow your priors, unless the stakes and uncertainty warrant more complex consequence estimates. You can have a small prior toward inaction, so that not every random action is worth considering. You can also blend in some virtue ethics, by having a prior that virtuous acts often lead to greater total happiness in the long run.

What I described is a more Bayesian version of R. M. Hare's "Two-level utilitarianism", which involves an "intuitive" and a "critical" level of moral thinking.

Thursday, 24 July 2025Thu, 24 Jul 2025

Thursday, 24 July 2025

Thu, 24 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Personal Blogposts

Quick takes

From https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.03079

[...]

I remember reading something similar on this a while ago, possibly on this forum, but I can't find anything at the moment, does anyone remember any other papers/posts on the topic?

Hey everyone! As a philosophy grad transitioning into AI governance/policy research or AI safety advocacy, I'd love advice: which for-profit roles best build relevant skills while providing financial stability?

Specifically, what kinds of roles (especially outside of obvious research positions) are valuable stepping stones toward AI governance/policy research? I don’t yet have direct research experience, so I’m particularly interested in roles that are more accessible early on but still help me develop transferable skills, especially those that might not be intuitive at first glance.

My secondary interest is in AI safety advocacy. Are there particular entry-level or for-profit roles that could serve as strong preparation for future advocacy or field-building work?

A bit about me:

– I have a strong analytical and critical thinking background from my philosophy BA, including structured and clear writing experience

– I’m deeply engaged with the AI safety space: I’ve completed BlueDot’s AI Governance course, volunteered with AI Safety Türkiye, and regularly read and discuss developments in the field

– I’m curious, organized, and enjoy operations work, in addition to research and strategy

If you've navigated a similar path, have ideas about stepping-stone roles, or just want to chat, I'd be happy to chat over a call as well! Feel free to schedule a 20-min conversation here.

Thanks in advance for any pointers!

Wednesday, 23 July 2025Wed, 23 Jul 2025

Wednesday, 23 July 2025

Wed, 23 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Personal Blogposts

Quick takes

AI risk in Depth, in the mainstream!

Perhaps the most popular British Podcast, the Rest is Politics has just spent 23 minutes in one of the most compelling and straightforward explanations of AI risk I've heard anywhere, let alone in the mainstream media. The first 5 minutes of the discussion is especially good as an explainer and then there's a more wide ranging discussion after that.

Recommended sharing with non-EA friends, especially in England as this is a respected mainstream podcasts that not many people will find weird - Minute 16 to 38. He also discusses (near the end) his personal journey of how he became scared of AI which is super cool.

I don't love his solution of England and EU building their own "honest" models, but hey most of it is great.

Also a shoutout as well to any of you in the background who might have played a part in helping Rory Stewart think about this more deeply.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/23/health/pepfar-shutdown.html

Pepfar maybe still being killed off after all :(

I wonder if it would be interesting to use PPP-adjusted sale price of high-end luxury or Veblen goods as a metric for moral progress of humanity (I suspect on this metric, we'd look like we were getting progressively worse, but I'm unclear if that's a bug or a feature).

Tuesday, 22 July 2025Tue, 22 Jul 2025

Tuesday, 22 July 2025

Tue, 22 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Quick takes

Not sure if relevant, but I've written up a post offering my take on the "unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics." My core argument is that we can potentially resolve Wigner's puzzle by applying an anthropic filter, but one focused on the evolvability of mathematical minds rather than just life or consciousness.

The thesis is that for a mind to evolve from basic pattern recognition to abstract reasoning, it needs to exist in a universe where patterns are layered, consistent, and compounding. In other words, a "mathematically simple" universe. In chaotic or non-mathematical universes, the evolutionary gradient towards higher intelligence would be flat or negative.

Therefore, any being capable of asking "why is math so effective?" would most likely find itself in a universe where it is.

I try to differentiate this from past evolutionary/anthropic arguments and address objections (Boltzmann brains, simulation, etc.). I'm particularly interested in critiques of the core "evolutionary gradient" claim and the "distribution of universes" problem I bring up near the end.

The argument spans a number of academic disciplines, however I think it most centrally falls under "philosophy of science." At any rate, I'm happy to clear up any conceptual confusions or non-standard uses of jargon in the comments.

Looking forward to the discussion.

----------------------------------------

Imagine you're a shrimp trying to do physics at the bottom of a turbulent waterfall. You try to count waves with your shrimp feelers and formulate hydrodynamics models with your small shrimp brain. But it’s hard. Every time you think you've spotted a pattern in the water flow, the next moment brings complete chaos. Your attempts at prediction fail miserably. In such a world, you might just turn your back on science and get re-educated in shrimp grad school in the shrimpanities to study shrimp poetry or shrimp ethics or something.

So why do human mathematicians and physicists have it much easie

Hi all,

What I find an interesting perspective is to approach ethics from the point of view of a “network.” In our case, a network in which humans (or, more precisely, our intelligences) are the nodes, and the relationships between these intelligences are the edges.

For this network to exist, the nodes need to establish and maintain relationships. This “edge maintenance” can, in turn, be translated into what we call ethics or ethical behaviour. Whatever creates or restores these edges/relationships—and thereby enables the existence of the network—is just, correct, or virtuous. This is because, to make the intelligent nodes physically exist (to keep their substrate intact), the network itself must exist: the nodes are interdependent. One node grows wheat, another harvests it, another bakes bread, another distributes it, etc. Thus, ethics becomes about existence, which is much easier to comprehend.

Once you embrace this network between intelligent nodes, you can also start thinking about all subsequent dependencies in terms of nodes and edges/relationships. This neatly highlights the interdependences of our existence and leads me to formulate the meaning of life as: “Keep alive what keeps us/you alive.” As this becomes the internal logic of this interdependent network.

I’m curious who else finds this perspective interesting, as I believe that using the language of networks and complex systems in this context opens the door to thinking and talking more clearly about intelligence and AI alignment, (inter)national collaboration, (bio)diversity, evolution, etc

Topic Page Edits and Discussion

Monday, 21 July 2025Mon, 21 Jul 2025

Monday, 21 July 2025

Mon, 21 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Quick takes

Giving What We Can is about to hit 10,000 pledgers. (9935 at the time of writing)

If you're on the fence and wanna be in the 4 digit club, consider very carefully whether you should make the pledge! An important reminder that Earning to Give is a valid way to engage with EA.

I wrote up something for my personal blog about my relationship with effective altruism. It's intended for a non-EA audience - at this point my blog subscribers are mostly friends and family - so I didn't think it was worth cross posting as I spend a lot of time trying to explain what effective altruism is exactly, but some people might still be interested. My blog mostly is about books and whatnot, not effective altruism, but if I do write some more detailed stuff on effective altruism I will try to post it to the forum also.

Sunday, 20 July 2025Sun, 20 Jul 2025

Sunday, 20 July 2025

Sun, 20 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Quick takes

Fun anecdote from Richard Hamming about checking the calculations used before the Trinity test:

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Hamming

Saturday, 19 July 2025Sat, 19 Jul 2025

Saturday, 19 July 2025

Sat, 19 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Quick takes

AI governance could be much more relevant in the EU, if the EU was willing to regulate ASML. Tell ASML they can only service compliant semiconductor foundries, where a "compliant semicondunctor foundry" is defined as a foundry which only allows its chips to be used by compliant AI companies.

I think this is a really promising path for slower, more responsible AI development globally. The EU is known for its cautious approach to regulation. Many EAs believe that a cautious, risk-averse approach to AI development is appropriate. Yet EU regulations are often viewed as less important, since major AI firms are mostly outside the EU. However, ASML is located in the EU, and serves as a chokepoint for the entire AI industry. Regulating ASML addresses the standard complaint that "AI firms will simply relocate to the most permissive jurisdiction". Advocating this path could be a high-leverage way to make global AI development more responsible without the need for an international treaty.

If you're considering a career in AI policy, now is an especially good time to start applying widely as there's a lot of hiring going on right now. I documented in my Substack over a dozen different opportunities that I think are very promising.

Topic Page Edits and Discussion

Friday, 18 July 2025Fri, 18 Jul 2025

Friday, 18 July 2025

Fri, 18 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Topic Page Edits and Discussion

Thursday, 17 July 2025Thu, 17 Jul 2025

Thursday, 17 July 2025

Thu, 17 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Wednesday, 16 July 2025Wed, 16 Jul 2025

Wednesday, 16 July 2025

Wed, 16 Jul 2025

Frontpage Posts

Personal Blogposts

Quick takes

Probably(?) big news on PEPFAR (title: White House agrees to exempt PEPFAR from cuts): https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/5402273-white-house-accepts-pepfar-exemption/. (Credit to Marginal Revolution for bringing this to my attention)

Mini EA Forum Update

We've added two new kinds of notifications that have been requested multiple times before:

1. Notifications when someone links to your post, comment, or quick take

1. These are turned on by default — you can edit your notifications settings via the Account Settings page.

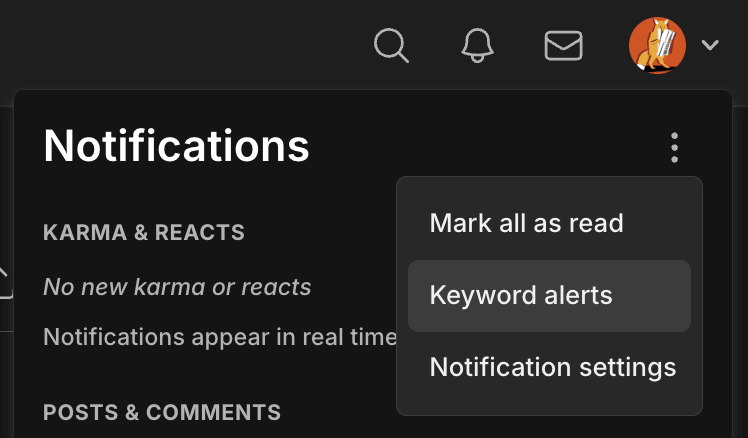

2. Keyword alerts

1. You can manage your keyword alerts here, which you can get to via your Account Settings or by clicking the notification bell and then the three dots icon.

2. You can quickly add an alert by clicking "Get notified" on the search page. (Note that the alerts only use the keyword, not any search filters.)

3. You get alerted when the keyword appears in a newly published post, comment, or quick take (so this doesn't include, for example, new topics).

4. You can also edit the frequency of both the on-site and email versions of these alerts independently via the Account Settings page (at the bottom of the Notifications list).

5. See more details in the PR

I hope you find these useful! 😊 Feel free to reply if you have any feedback or questions.

I've updated the public doc that summarizes the CEA Online Team's OKRs to add Q3.1 (sorry this is a bit late, I just forgot! 😅).

Hello everyone,

I recently came across a book titled “Technical Control Problem and Potential Capabilities of Artificial Intelligence” by Dr. Hüseyin Gürkan Abalı. It claims to offer a technical and philosophical framework regarding the control problem in advanced AI systems, and discusses their potential future capabilities.

As someone interested in AI safety and ethics, I’m curious if anyone here has read the book or has any thoughts on its relevance or quality.

I would appreciate any reviews, critiques, or academic impressions.

Thanks in advance!

Act utilitarians choose actions estimated to increase total happiness. Rule utilitarians follow rules estimated to increase total happiness (e.g. not lying). But you can have the best of both: act utilitarianism where rules are instead treated as moral priors. For example, having a strong prior that killing someone is bad, but which can be overridden in extreme circumstances (e.g. if killing the person ends WWII).

These priors make act utilitarianism more safeguarded against bad assessments. They are grounded in Bayesianism (moral priors are updated the same way as non-moral priors). They also decrease cognitive effort: most of the time, just follow your priors, unless the stakes and uncertainty warrant more complex consequence estimates. You can have a small prior toward inaction, so that not every random action is worth considering. You can also blend in some virtue ethics, by having a prior that virtuous acts often lead to greater total happiness in the long run.

What I described is a more Bayesian version of R. M. Hare's "Two-level utilitarianism", which involves an "intuitive" and a "critical" level of moral thinking.